Speaking of South Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imaginationland," Terrorism, and the Difference Between Real And

Christopher C. Kirby, PhD. Eastern Washington University Cheney, WA. 99004 “IMAGINATIONLAND,” TERRORISM, AND THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN REAL AND IMAGINARY CHRISTOPHER C. KIRBY Eastern Washington University “Ladies and gentlemen, I have dire news. Yesterday, at approximately 18:00 hours, terrorists successfully attacked... our imagination”1 “Imaginationland” was an Emmy winning, three-part story which aired as the tenth, eleventh and twelfth episodes of South Park’s eleventh season and was later re-issued as a movie with all of the deleted scenes included. The story begins with the boys waiting in the woods for a leprechaun that Cartman claims to have seen. Kyle, ever the skeptic, has bet ten dollars against sucking Cartman’s balls that leprechauns aren’t real. When the boys finally trap one, to Kyle’s shock and dismay, it cryptically warns of a terrorist attack and disappears. That night at the dinner table Kyle asks his parents where leprechauns come from and why one would visit South Park to warn of a terrorist attack. They chide him for not knowing the difference between real and imaginary and he mutters, “I thought I did.” What ensues is pure South Park genius as we discover that, in fact, nobody seems to know what the difference is. As the story unfolds it’s obvious that no one will be safe, as the episode lampoons the U.S. “war on terror,” the American legal system, Hollywood directors, the media, Christianity, the military, Kurt Russell, and Al Gore’s campaign against climate change [ManBearPig is real… I’m super cereal!] all the while reminding us that imagination is an essential feature of human life. -

View/Method……………………………………………………9

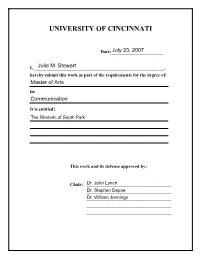

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________July 23, 2007 I, ________________________________________________Julie M. Stewart _________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Communication It is entitled: The Rhetoric of South Park This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Dr. John Lynch _______________________________Dr. Stephen Depoe _______________________________Dr. William Jennings _______________________________ _______________________________ THE RHETORIC OF SOUTH PARK A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research Of the University of Cincinnati MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Communication, of the College of Arts and Sciences 2007 by Julie Stewart B.A. Xavier University, 2001 Committee Chair: Dr. John Lynch Abstract This study examines the rhetoric of the cartoon South Park. South Park is a popular culture artifact that deals with numerous contemporary social and political issues. A narrative analysis of nine episodes of the show finds multiple themes. First, South Park is successful in creating a polysemous political message that allows audiences with varying political ideologies to relate to the program. Second, South Park ’s universal appeal is in recurring populist themes that are anti-hypocrisy, anti-elitism, and anti- authority. Third, the narrative functions to develop these themes and characters, setting, and other elements of the plot are representative of different ideologies. Finally, this study concludes -

South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review South Park the Fractured but Whole Free Download Review

south park the fractured but whole free download review South park the fractured but whole free download review. South Park The Fractured But Whole Crack Whole, players with Coon and Friends can dive into the painful, criminal belly of South Park. This dedicated group of criminal warriors was formed by Eric Cartman, whose superhero alter ego, The Coon, is half man, half raccoon. Like The New Kid, players will join Mysterion, Toolshed, Human Kite, Mosquito, Mint Berry Crunch, and a group of others to fight the forces of evil as Coon strives to make his team of the most beloved superheroes in history. Creators Matt South Park The Fractured But Whole IGG-Game Stone and Trey Parker were involved in every step of the game’s development. And also build his own unique superpowers to become the hero that South Park needs. South Park The Fractured But Whole Codex The player takes on the role of a new kid and joins South Park favorites in a new extremely shocking adventure. The game is the sequel to the award-winning South Park The Park of Truth. The game features new locations and new characters to discover. The player will investigate the crime under South Park. The other characters will also join the player to fight against the forces of evil as the crown strives to make his team the most beloved South Park The Fractured But Whole Plaza superheroes in history. Try Marvel vs Capcom Infinite for free now. The all-new dynamic control system offers new possibilities to manipulate time and space on the battlefield. -

Stream South Park Online Free No Download Stream South Park Online Free No Download

stream south park online free no download Stream south park online free no download. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67dbdf08ddb7c40b • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. Stream south park online free no download. Watch full episodes of your favorite shows with the Comedy Central app.. Enjoy South Park, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Broad City and many more, . New episodes of “South Park” will now go through many windows — on television on Comedy Central, on the web at SouthParkStudios for . How to watch South Park on South Park Studios: · Go to: http://southpark.cc.com/.. · Select “Full episodes” from the top menu.. south park episodes. South Park Zone South Park Season 23.. Watch all South Park episodes from Season 23 online . "Mexican Joker" is the first episode of the twenty-third season of . seasons from many popular shows exclusively streaming on Hulu including Seinfeld, Fargo, South Park and Fear the Walking Dead. -

Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross

Excremental Ecstasy, Divine Defecation and Revolting Reception: Configuring a Scatological Gaze in Trash Filmmaking Zoe Gross Scatology, for all the sordid formidability the term evokes, is not an es- pecially novel or unusual theme, stylistic technique or descriptor in film or filmic reception. Shit happens – to emphasise both the banality and perva- siveness of the cliché itself – on multiple levels of textuality, manifesting it- self in both the content and aesthetic of cinematic texts, and the ways we respond to them. We often refer to “shit films,” using an excremental vo- cabulary redolent of detritus, malaise and uncleanliness to denote their otherness and “badness”. That is, films of questionable taste, aesthetics, or value, are frequently delineated and defined by the defecatory: we describe them as “trash”, “crap”, “filth”, “sewerage”, “shithouse”. When considering cinematic purviews such as the b-film, exploitation, and shock or trash filmmaking, whose narratives are so often played out on the site of the gro- tesque body, a screenscape spectacularly splattered with bodily excess and waste is de rigeur. Here, the scatological is both often on blatant dis- play – shit is ejected, consumed, smeared, slung – and underpining or tinc- turing form and style, imbuing the text with a “shitty” aesthetic. In these kinds of films – which, as their various appellations tend to suggest, are de- fined themselves by their association with marginality, excess and trash, the underground, and the illicit – the abject body and its excretia not only act as a dominant visual landscape, but provide a kind of somatic, faecal COLLOQUY text theory critique 18 (2009). -

HBO Max Will Be More Expensive Than Netflix, Disney Or Apple

HBO Max will be more expensive than Netflix, Disney or Apple. Does that mean it'll be a tough sell? 31 October 2019, by Jefferson Graham Now try $14.99 monthly for HBO Max. That's not a misprint. The most popular tier on Netflix, which has been streaming since 2013 and is the undisputed leader in the field, is $12.99. For your $15, Warner is giving you a lot: Some 10,000 hours of content, new and old fare from the libraries of Warner Bros., HBO, CNN, TNT, TBS, the Cartoon Network, Adult Swim, Turner Classic Movies and DC Comics. Warner announced a giant slate of projects, including a prequel to HBO's Game of Thrones, Credit: CC0 Public Domain new movies with Reese Witherspoon and Meryl Streep, revivals of the classic Looney Tunes (Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig) cartoons and a new series featuring the Hanna Barbera characters (The Welcome to the hard sell. Flintstones, Jetsons, Yogi Bear, Mr. Jinx) called "Jellystone." HBO Max won't debut until May, but AT&T's Warner Media wanted to get a quick attention grab The complete seasons of "South Park," "Friends" on consumers during a week that will see Apple and "The Big Bang Theory" are coming to HBO enter the streaming wars and Disney join two Max, along with dozens of movies from the Warner weeks later. Bros. library, everything from the "Joker" and "Batman" movies to "Casablanca" and both the HBO staged a giant presentation on a historic Judy Garland and Lady Gaga versions of "A Star Is soundstage at the Warner Bros. -

South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, the Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W

University of Texas at El Paso DigitalCommons@UTEP Open Access Theses & Dissertations 2009-01-01 South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan University of Texas at El Paso, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Dungan, Drew W., "South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism" (2009). Open Access Theses & Dissertations. 245. https://digitalcommons.utep.edu/open_etd/245 This is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies, The Art of Stealthy Conservatism Drew W. Dungan Department of Communication APPROVED: Richard D. Pineda, Ph.D., Chair Stacey Sowards, Ph.D. Robert L. Gunn, Ph.D. Patricia D. Witherspoon, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Copyright © by Drew W. Dungan 2009 Dedication To all who have been patient and kind, most of all Robert, Thalia, and Jesus, thank you for everything... South Park and Absurd Culture War Ideologies. The Art of Stealthy Conservatism by DREW W. DUNGAN, B.A. THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at El Paso in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Communication THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT EL PASO May 2009 Abstract South Park serves as an example of satire and parody lampooning culture war issues in the popular media. -

PDF Download South Park Drawing Guide : Learn To

SOUTH PARK DRAWING GUIDE : LEARN TO DRAW KENNY, CARTMAN, KYLE, STAN, BUTTERS AND FRIENDS! PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Go with the Flo Books | 100 pages | 04 Dec 2015 | Createspace Independent Publishing Platform | 9781519695369 | English | none South Park Drawing Guide : Learn to Draw Kenny, Cartman, Kyle, Stan, Butters and Friends! PDF Book Meanwhile, Butters is sent to a special camp where they "Pray the Gay Away. See more ideas about south park, south park anime, south park fanart. After a conversation with God, Kenny gets brought back to life and put on life support. This might be why there seems to be an air of detachment from Stan sometimes, either as a way to shake off hurt feelings or anger and frustration boiling from below the surface. I was asked if I could make Cartoon Animals. Whittle his Armor down and block his high-powered attacks and you'll bring him down, faster if you defeat Sparky, which lowers his defense more, which is recommended. Butters ends up Even Butters joins in when his T. Both will use their boss-specific skill on their first turn. Garrison wielding an ever-lively Mr. Collection: Merry Christmas. It is the main protagonists in South Park cartoon movie. Climb up the ladder and shoot the valve. Donovan tells them that he's in the backyard. He can later be found on the top ramp and still be aggressive, but cannot be battled. His best friend is Kyle Brovlovski. Privacy Policy.. To most people, South Park will forever remain one of the quirkiest and wittiest animated sitcoms created by two guys who can't draw well if their lives depended on it. -

Karaoke by Keysdan Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird'

Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Artist Title 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song 'Weird' Al Yankovic Achy Breaky Song Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Addicted To Spuds 'Weird' Al Yankovic Alimony 'Weird' Al Yankovic Amish Paradise 'Weird' Al Yankovic Another Rides The Bus 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem 'Weird' Al Yankovic Bedrock Anthem Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid 'Weird' Al Yankovic Dare To Be Stupid Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Eat It 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ebay 'Weird' Al Yankovic Fat 'Weird' Al Yankovic Grapefruit Diet 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump 'Weird' Al Yankovic Gump Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Lost On Jeopardy 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Love Rocky Road 'Weird' Al Yankovic I Want A New Duck 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums 'Weird' Al Yankovic It's All About The Pentiums Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon 'Weird' Al Yankovic Like A Surgeon Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic My Bologna 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute 'Weird' Al Yankovic One More Minute Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Phony Calls 'Weird' Al Yankovic Ricky 'Weird' Al Yankovic Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic She Drives Like Crazy 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana 'Weird' Al Yankovic Smells Like Nirvana Wvocal 'Weird' Al Yankovic Spam 'Weird' Al Yankovic The Saga Begins 'Weird' Al Yankovic Yoda 'Weird' Al Yankovic You Don't Love Me Anymore 2 Live Crew Me So Horny Adam Sandler At A Medium Pace (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Ode To My Car Adam Sandler Ode To My Car (ADVISORY) Adam Sandler Piece Of S--t Car Adam Sandler What The H--- Happened To Me Adam Sandler What The Hell Happened To Me www.KeysDAN.com 501.470.6386 Karaoke by KeysDAN Comedy Bill Clinton Parody Bimbo No.5 Britney Spears Parody Oops I Farted Again CLEDUS T JUDD MY CELLMATE THINKS I'M SEXY Cheech & Chong Earache My Eye Chef Chocolate Salty Balls Chef Love Gravy Chef No Substitute, Oh Kathy Lee Chef Simultaneous Chef & Meatloaf Tonight Is Right for Love Chef & No Substitute Oh Kathy Lee Chef (South Park) Chocolate Salty Balls (P.S. -

2016 Popular Annual Financial Report

CHICAGO PARK DISTRICT Chicago, Illinois Children First Built to Last Best Deal in Town Extra Effort Popular Annual Financial Report For the Year Ended December 31, 2016 Prepared by the Chief Financial Officer and the Office of the Comptroller Rahm Emanuel, Mayor, City of Chicago Jesse H. Ruiz, President of the Board of Commissioners Michael P. Kelly, General Superintendent and Chief Executive Officer Steve Lux, Chief Financial Officer Cecilia Prado, CPA, Comptroller TABLE OF CONTENTS Commissioner’s Letter…………………………………………………………………………………………...….1 Comptroller’s Message……………………………………………………………………………………………...2 Organizational Structure & Management…………...……………………………………………………..3 Map of Parks……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Staffed Locations…………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..5 Operating Indicators………………………………………………………………………………………………....6 CPD Spotlight………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…7 Core Values Children First……………………………………………………………………………………………………...8 Best Deal in Town……………………………………………………..………………………………………..9 Built to Last……………………………………………………………………………………………………….10 Extra Effort………………………………………………………………………………………………………..11 Management’s Discussion & Analysis………………………………………………………………….12-16 Local Economy………………………………………………………………………………………………………...17 Capital Improvement Projects………………………………………………………………………………….18 Community Efforts…………………………………………………………………………………………………..19 Privatized Contracts………………………………………………………………………………………………...20 Featured Parks………………………………………………………………………………....inside back cover Contact Us…………………………………………………………………………………………………..back -

PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues Through Satire

Colloquy Vol. 12, Fall 2016, pp. 101-114 PC Is Back in South Park: Framing Social Issues through Satire Alex Dejean Abstract This study takes an extensive look at the television program South Park episode “Stunning and Brave.” There is limited research that explores the use of satire to create social discourse on concepts related to political correctness. I use framing theory as a primary variable to understand the messages “Stunning and Brave” attempts to convey. Framing theory originated from the theory of agenda setting. Agenda setting explains how media depictions affect how people think about the world. Framing is an aspect of agenda setting that details the organization and structure of a narrative or story. Framing is such an important variable to agenda setting that research on framing has become its own field of study. Existing literature of framing theory, comedy, and television has shown how audiences perceive issues once they have been exposed to media messages. The purpose of this research will review relevant literature explored in this area to examine satirical criticism on the social issue of political correctness. It seems almost unnecessary to point out the effect media has on us every day. Media is a broad term for the collective entities and structures through which messages are created and transmitted to an audience. As noted by Semmel (1983), “Almost everyone agrees that the mass media shape the world around us” (p. 718). The media tells us what life is or what we need for a better life. We have been bombarded with messages about what is better. -

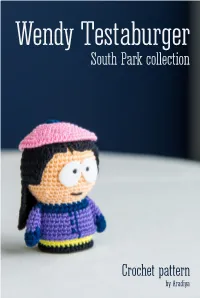

Eng Tutorial Wendy

Wendy Testaburger South Park collection Crochet pattern by Aradiya 1 Instruments and materials 1.25 and 2.00 mm hooks Purple, navy blue, pink, flesh-colored, yellow and black yarn Sewing needle Stung material A piece of white felt Image 1 Wendy Testaburger - character of the popular cartoon “South Park”. To create a toy with a height of 7.5 cm you must crochet with single yarn using a 2.00 mm hook. The arms, the hair and the hat are crocheted with single yarn using a 1.25 mm hook. The stung material used in this toy is polyester wadding. The piece of felt must be 1.5 mm thick. This pattern is for personal use only. Sharing information from this pattern is prohibited. If you publish photos of the toys that are crocheted following this pattern, it is better to mention the author of the pattern. You can also use hashtag #AradiyaToys at Twitter and Instagram to share your toy and see other toys that are created following AradiyaToys’ patterns. 2 Abbreviations Ch - chain Sl - slip stitch Sc - single crochet Dc - double crochet HDc - half double crochet INC - increase INVDEC - invisible decrease BLO - back loops only FLO - front loops only Tip 1 The toy must be All amigurumi toys crocheted with tight are crocheted with tight stitches. Avoid stitches, to be sure that small holes when there won't be any holes stretching crochet through which stung fabric, if there are material can some tiny holes, be seen. use a smaller size hook. To avoid seams, all details are crocheted in a spiral without slip stitch and lifting loops.