The Occult Pneumothorax: What Have We Learned?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

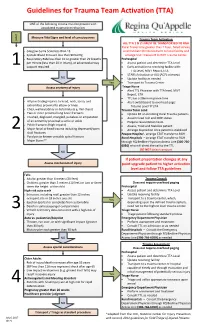

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

Anytown Trauma Center Trauma Protocols

ANYTOWN TRAUMA CENTER TRAUMA PROTOCOLS TITLE: TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTOCOL PURPOSE: The purpose of the protocol is to establish guidelines for trauma team activation and define the members of the responding trauma team to facilitate the resuscitation and management of critical or seriously injured patients who require rapid, organized resuscitation, evaluation and stabilization to promote optimal outcomes. It also serves to provide triage guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. PROCESS: 1. TRAUMA TEAM ACTIVATION PROTCOL A. The criteria for activation of the trauma team is clearly defined and posted at the Emergency Department triage desk, by the EMS communication station and in the resuscitation rooms. B. The trauma team may be activated prior to arrival based on the EMS communication and their assessment. C. The trauma surgeon, emergency medicine physician, emergency department charge nurse/ house supervisor, emergency department nurses and the Trauma Program Manager may activate the trauma team. D. The person calling the trauma activation will initiate the trauma page to group page the trauma team and will specify the MOI, BP, HR, ETA and level of activation required and age if available. E. If the trauma team members are present in the emergency department and alert is still communicated to ensure everyone is notified. F. Trauma team member notification and arrival times will be documented on the trauma flow sheet (paper or electronic). G. Trauma team members will sign-in when they arrive. H. Trauma team members will be activated for all patients who meet the following criteria: 1. Level 1 trauma activation (major): life threatening injuries and/or unstable vital signs, limb-threating or disability threatening injury 2. -

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions

Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital through the Emergency Department Test Questions 1. As the prehospital provider approaches the scene of a trauma call, they perform a. a radio transmission to the hospital b. a scene size up c. an estimate of neck size for c-collar d. an estimate of victim’s height and weight 2. Field intubation has been proven to improve outcome in a. patients with BP less than 90 mm Hg b. patients with GCS less than 9 c. patients with acute respiratory distress d. none of the above 3. A proven technique of hemorrhage control is a. Direct pressure b. Elevate above the heart c. Pressure points d. Cold application 4. Prehospital care for apparent pelvic fractures includes a. DO NOT ROCK or palpate the pelvis in the prehospital arena b. Avoid log rolling as much as possible c. Apply splint if in your area protocols d. All of the above 5. Most preventable deaths in trauma care are due to a. Delay in CPR b. Cardiac tamponade c. Airway obstruction d. Tension pneumothorax STN 2012 Electronic Library: Chapter 1 - Trauma Team from Prehospital Through the Emergency Department Test Questions 2 6. For resuscitation to occur, there must be a. Cellular perfusion and tissue oxygenation b. Restoration of a blood pressure greater than 90mm Hg c. A hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL d. A PaO2 greater than 80 mm Hg 7. The Trauma Triad of Death is a. Hypotension, tachycardia and decreased urine output b. Infection, inadequate nutrition, DVT’s c. Hypothermia, acidosis and coagulopathy d. -

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC

Basic Trauma Overview - ABC Dale Dangleben, MD, FACS 1 2 Team 3 Extended Team 4 Team Leader Decrease chaos / optimize care. – Remains calm – Maintains control and provides direction – Stays decisive – Sees the big picture (situational awareness) – Is open to other team members input – Directs resuscitation – Makes early decision to transfer the patients that exceed the local capabilities 5 Team Members − Know your roles in the trauma team − Remain calm − Be responsive to team leader −Voice suggestions or concerns 6 Responsibilities – Perform the Primary and secondary survey – Verbalize patient care – Report completed tasks 7 Responsibilities – Monitors the patient – Manual BP – Obtains IV access – Administers medications – Dresses wounds – Performs or assists in resuscitative procedures 8 Responsibilities Records data Ensures documentation accompanies patient upon transfer Assists team members as needed 9 Responsibilities – Obtains needed supplies – Coordinates communication with local and external resources – Assists team members as needed 10 Responsibilities • Place Oxygen on patient • Manage airway • Hold C spine • Manage ventilator if • Manage rapid infuser line patient intubated where indicated • Assists team members as needed 11 Organization of trauma resuscitation area – Basic adult and pediatric equipment for: • Airway management (cart) • IV access with warm fluids • Chest tube insertion • Hemorrhage control (tourniquets, pelvic binders) • Immobilization • Medications • Pediatric length/weight based tape (Broselow Tape) – Warming -

Early Acute Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: a Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals

SPINAL CORD MEDICINE EARLY ACUTE EARLY MANAGEMENT Early Acute Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Professionals Administrative and financial support provided by Paralyzed Veterans of America CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE: Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Member Organizations American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation American Association of Neurological Surgeons American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Nurses American Association of Spinal Cord Injury Psychologists and Social Workers American College of Emergency Physicians American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine American Occupational Therapy Association American Paraplegia Society American Physical Therapy Association American Psychological Association American Spinal Injury Association Association of Academic Physiatrists Association of Rehabilitation Nurses Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation Congress of Neurological Surgeons Insurance Rehabilitation Study Group International Spinal Cord Society Paralyzed Veterans of America Society of Critical Care Medicine U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs United Spinal Association CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Spinal Cord Medicine Early Acute Management in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Health-Care Providers Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Administrative and financial support provided by Paralyzed Veterans of America © Copyright 2008, Paralyzed Veterans of America No copyright ownership -

Anesthesia for Orthopedic Trauma

10 Anesthesia for Orthopedic Trauma Jessica A. Lovich-Sapola and Charles E. Smith Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine Department of Anesthesia, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland USA 1. Introduction Orthopedic trauma surgeons realize the tremendous importance of coordinated care at trauma centers and by trauma systems. The anesthesiologist is an important link in the coordinated approach to orthopedic trauma care. “Musculoskeletal injuries are the most frequent indication for operative management in most trauma centers.” Trauma management of a multiply-injured patient includes early stabilization of long-bone, pelvic, and acetabular fractures, provided that the patient has been adequately resuscitated. (Miller, 2009) Early stabilization leads to reduced pain and improved outcomes. (Smith, 2008) Studies have shown that failure to stabilize these fractures leads to increased morbidity, pulmonary complications, and increased length of hospital stay. (Miller, 2009) “Life threatening and limb-threatening musculoskeletal injuries should be addressed emergently.” (Smith, 2008) The chapter will discuss the following orthopedic trauma anesthesia issues: Pre-operative evaluation Airway management including difficult airways and cervical spine precautions Intra-operative monitoring Anesthetic agents and techniques (regional vs general anesthesia) Intra-operative complications (hypotension, blood loss, hypothermia, fat embolism syndrome) Post-operative pain management 2. Pre-operative evaluation Orthopedic trauma patients can be challenging for Anesthesiologists. These patients can range in age from young to the elderly, may have multiple co-morbid medical conditions, and even a previously healthy patient may have trauma-associated injuries that may have a significant impact on the anesthetic plan. The Anesthesiologist’s role is to evaluate the entire patient, with particular focus on the cardiovascular, respiratory, and other major organ system function. -

Traumatic Brain Injury

Traumatic Brain Injury Early Care and Hospitalization Family Guide Table of Contents Introduction . .3 Types of Brain Injuries . .4 Who Will Care for My Loved One and What Can I Expect to See in the Room? . .7 How Are Brain Injuries Evaluated? . .8 How Are Brain Injuries Treated? . .9 Levels of Care . .11 How Do Patients Respond after Severe Brain Injury? . .14 Impact on the Family . .16 What Happens Next? . .18 Introduction The purpose of this booklet is to provide you with information to help you understand traumatic brain injury (TBI), how the brain works and some of the medical care that your loved one will receive. Use this booklet as a guide, but continue to ask questions of your loved one’s treatment team. They are here to help both you and your loved one through this journey. What Does It Mean That My Loved One Has a Traumatic Brain Injury? A TBI is an injury to the brain that can cause a variety of physical and cognitive difficulties. The brain controls everything we do, including breathing, sensation, movement, emotions and thinking. Trauma from an external force, such as hitting the head against something, can result in bruising, bleeding, twisting or tearing of the brain, leading to damage. How Serious Is a Traumatic Brain Injury? Every brain injury is different, and the severity of a TBI can vary from very mild to severe. Your treatment team will provide you with ongoing information during hospitalization. A mild traumatic brain injury usually means that a person will have a good recovery over time and may cause no or very minimal disruption to normal activities. -

RCH Trauma Guideline Management of Traumatic Pneumothorax & Haemothorax

RCH Trauma Guideline Management of Traumatic Pneumothorax & Haemothorax Trauma Service, Division of Surgery Aim To describe safe and competent management of traumatic pneumothorax and haemothorax at RCH. Definition of Terms Haemothorax: collection of blood in the pleural space Pneumothorax: collection of air in the pleural space Tension Pneumothorax: one way valve effect which allows air to enter the pleural space, but not leave. Air and so intrapleural pressure (tension) builds up and forces a mediastinal shift. This leads to decreased venous return to the heart and lung collapse/compression causing acute life-threatening respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Ventilated patients are particularly at risk due to the positive pressure forcing more air into the pleural space. Tension pneumothorax results in rapid clinical deterioration and is an emergency. Finger thoracostomy: preferred method of emergency pleural decompression of a tension pneumothorax. It involves incising 3-4cm of skin over the 4th intercostal space just anterior to the mid-axillary line followed by blunt dissection to the pleura to allow introduction of a finger into the pleural space. Main Points 1. Management of a clinically significant traumatic pneumothorax or haemothorax typically requires pleural decompression by chest drain insertion. 2. Anatomical landmarks should be used to determine the site of incision for pleural decompression within the ‘triangle of safety’ to reduce risk of harm. 3. All patients in traumatic cardiac arrest who do not respond immediately to airway opening should have their pleural cavities decompressed by finger thoracostomy, concurrent with efforts to restore the circulating blood volume. 4. With few exceptions, chest drain insertion follows immediately after finger thoracostomy, with the caveat that the time and place of insertion must be consistent with the child’s overall clinical priorities. -

Penetrating Thoracic Trauma Clinical Pathway Johns Hopkins All Children’S Hospital Penetrating Thoracic Injury

JOHNS HOPKINS ALL CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL Penetrating Thoracic Trauma Clinical Pathway Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital Penetrating Thoracic Injury Clinical Pathway Table of Contents 1. Rationale 2. Background 3. Diagnosis 4. Clinical Management 5. Emergency Center 6. Discharge 7. References 8. Outcome Measures 9. Clinical Pathways Team Information Updated: December 2020 Owners: Trauma This pathway is intended as a guide for physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners and other healthcare providers. It should be adapted to the care of specific patient based on the patient’s individualized circumstances and the practitioner’s professional judgment. 1 Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital Penetrating Thoracic Trauma Clinical Pathway Rationale: This clinical pathway was developed by a consensus group of JHACH physicians, advanced practice providers, nurses and pharmacists to standardize the management of children presenting with penetrating thoracic injury. This guideline is designed to assist the emergency bedside provider with the potential decisions on diagnostics and disposition based on the clinical presentation of the patient Background Thoracic injury occurs infrequently in pediatrics but injuries can be immediately life threatening with mortality rates of 15-26%. Rapid and thorough assessment is necessary to prevent a bedside practitioner missing/delaying identification of and intervening with a life threatening injury. Diagnosis Information received pre arrival or at triage will help assist the bedside practitioner in identifying thoracic penetrating injury. For the unconscious patient, rapid and thorough primary and secondary assessment is necessary to find all injuries. Lab tests: CBC, CMP, T&S, PT/PTT Radiologic studies: CXR, Chest CT Clinical Management Determining stability of the patient on presentation is necessary to determine the immediate interventions necessary and to determine diagnostic and disposition options for treatment. -

1 Dr Roger Eltringham to Reply to Everyone Individually but Will

12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 1234567890123456789012345678901212345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345UPDATE IN 6 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 WA 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 A 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 12345678901234567890123456789012123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456 WORLD -

Alpha Activation1 Bravo Activation4

Trauma Care System Trauma Team Activation Criteria Alpha Activation1 • Confirmed blood pressure less than 90 mmHg at any time in adults and age-specific hypotension in children2; • Gunshot wounds to the neck, chest, abdomen or extremities proximal to the elbow/knee; • Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 9 with mechanism attributed to trauma; • Transfer patients from other hospitals receiving blood to maintain vital signs; • Intubated patients transferred from the scene, -OR- patients who have respiratory compromise or are in need of an emergent airway (includes intubated patients who are transferred from another facility with ongoing respiratory compromise) (does not include patients intubated at another facility who are now stable from a respiratory standpoint)3 • Emergency Physician/Hospital Provider Judgment Bravo Activation4 • All other penetrating injuries to the head, neck, chest, abdomen or extremities proximal to the elbow/knee; • Open or depressed skull fracture; • Paralysis or suspected spinal cord injury; • Flail chest; • Unstable pelvic fracture; • Amputation proximal to the wrist or ankle; • Two or more proximal long bone fractures (humerus or femur) • Crushed, degloved, or mangled extremity; • Falls: patients < 16 years: falls greater than 10 feet or 2-3 times the height of the child; patients ≥ 16 years: falls > 20 ft. (one story is equal to 10 ft.) • High Risk auto crash: intrusion, including roof: > 12 inches occupant site; intrusion > 18 inches any unoccupied site; ejection (partial or complete) from automobile; death