Spinal Trauma Guideline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Grant Program Report 2020

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Research Grant Program Report January 15, 2020 Author About the Minnesota Office of Higher Education Alaina DeSalvo The Minnesota Office of Higher Education is a Competitive Grants Administrator cabinet-level state agency providing students with Tel: 651-259-3988 financial aid programs and information to help [email protected] them gain access to postsecondary education. The agency also serves as the state’s clearinghouse for data, research and analysis on postsecondary enrollment, financial aid, finance and trends. The Minnesota State Grant Program is the largest financial aid program administered by the Office of Higher Education, awarding up to $207 million in need-based grants to Minnesota residents attending eligible colleges, universities and career schools in Minnesota. The agency oversees other state scholarship programs, tuition reciprocity programs, a student loan program, Minnesota’s 529 College Savings Plan, licensing and early college awareness programs for youth. Minnesota Office of Higher Education 1450 Energy Park Drive, Suite 350 Saint Paul, MN 55108-5227 Tel: 651.642.0567 or 800.657.3866 TTY Relay: 800.627.3529 Fax: 651.642.0675 Email: [email protected] Table of Contents Introduction 1 Spinal Cord Injury and Traumatic Brain Injury Advisory Council 1 FY 2020 Proposal Solicitation Schedule -

Suplento1 Volumen 71 En

S1 Volumen 71 Mayo 2015 Revista Española de Vol. 71 Supl. 1 • Mayo 2015 Vol. Clínica e Investigación Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de SEINAP Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría Sumario XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD espaÑOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIÁTRICOS Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015 MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO MONITORIZACIÓN? CRONIFICADO EN UCIP 1 Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación 47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP. de oxígeno? P. García Soler Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta 3 Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP 60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero 8 Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín CHARLA-COLOQUIO SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA 64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE? españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas. 13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada. J.C. de Carlos Vicente M.T. Alonso 68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: 20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira Intensivos Pediátricos. P. de la Oliva Senovilla Iglesias 72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas DE LA SECIP 23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, La comunicación efectiva. -

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

Degloving Injury: Different Ways of Management 76

CASE REPORT Journal of Nepalgunj Medical College, 2018 Degloving Injury: Different Ways of Management Nakarmi KK1, Shrestha SP2 ABSTRACT Degloving injury involves shearing of the skin from the underlying tissue due to differential gliding in response to the tangential force applied to the surface of the body leading to disruption of all the blood vessels connected to skin. The flap of degloved skin has precarious blood supply making it almost impossible for the flap to survive. We describe two cases of degloving of thigh managed differently in different settings. Keywords: degloving; excision; split skin graft INTRODUCTION management of these patients have been associated with Degloving injuries occur when there is sufficient tangential force lesser number of surgeries and shorter hospital stay6. Clinical to a body surface to disrupt the structures connecting skin and evaluation aided by use of fluorescein dye to assess the flap subcutaneous tissues to the superficial fascia. There may also be viability will guide whether skin can be harvested from the associated injuries to the underlying soft tissues, bone, nerves flap which can be stored for later use if general condition and vessels. It involves the young males, and most are related to does not allow immediate grafting7. Use of the degloved flap road traffic accident constituting upto 4% of all the trauma after defatting along with negative pressure wound therapy related admissions. Treatment guidelines are not clear1. The has also been described8. injury may be so severe that the limb is non-viable and requires amputation. It has been classified into three group based on Cases whether only skin, underlying soft tissue or bone is involved in Case 1 the injury process2. -

Major Extremity Trauma Module

MAJOR EXTREMITY TRAUMA MODULE INTRODUCTION Extremity trauma in general is extremely common, and may be characterised by the following: • Occur in isolation, or in the multiply injured patient; • Be limb threatening and occasionally life threatening • Occur secondary to blunt or penetrating trauma • Present with degrees of severity from a closed, neurovascularly intact simple fracture through to a mangled extremity or traumatic amputation • Involve skeletal, soft tissue, vascular and neurological structures in various combinations While the principles of assessment are consistent irrespective of the severity of the injury, this module does not specifically address simple closed fractures. Rather, this module focuses on the assessment and management of more severe limb trauma and its complications. The most common mechanisms for major extremity trauma are open fractures, crush injuries and major soft tissue injury from motor vehicle crashes, pedestrian injuries, falls from heights and industrial accidents. 1 The lower limb is more frequently involved than the upper limb. Penetrating trauma resulting in vascular injuries is unfortunately increasing in frequency. Assessment and management of major extremity trauma must occur in the context of assessing and managing the patient as a whole. Life-threatening injuries, which should be identified as part of the primary survey, will always take precedence over limb-threatening injuries, which may not be identified until the secondary survey. Life threatening extremity injuries include: • Pelvic -

T5 Spinal Cord Injuries

Spinal Cord (2020) 58:1249–1254 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-0506-7 ARTICLE Predictors of respiratory complications in patients with C5–T5 spinal cord injuries 1 2,3 3,4 1,5 1,5 Júlia Sampol ● Miguel Ángel González-Viejo ● Alba Gómez ● Sergi Martí ● Mercedes Pallero ● 1,4,5 3,4 1,4,5 1,4,5 Esther Rodríguez ● Patricia Launois ● Gabriel Sampol ● Jaume Ferrer Received: 19 December 2019 / Revised: 12 June 2020 / Accepted: 12 June 2020 / Published online: 24 June 2020 © The Author(s), under exclusive licence to International Spinal Cord Society 2020 Abstract Study design Retrospective chart audit. Objectives Describing the respiratory complications and their predictive factors in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injuries at C5–T5 level during the initial hospitalization. Setting Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona. Methods Data from patients admitted in a reference unit with acute traumatic injuries involving levels C5–T5. Respiratory complications were defined as: acute respiratory failure, respiratory infection, atelectasis, non-hemothorax pleural effusion, 1234567890();,: 1234567890();,: pulmonary embolism or haemoptysis. Candidate predictors of these complications were demographic data, comorbidity, smoking, history of respiratory disease, the spinal cord injury characteristics (level and ASIA Impairment Scale) and thoracic trauma. A logistic regression model was created to determine associations between potential predictors and respiratory complications. Results We studied 174 patients with an age of 47.9 (19.7) years, mostly men (87%), with low comorbidity. Coexistent thoracic trauma was found in 24 (19%) patients with cervical and 35 (75%) with thoracic injuries (p < 0.001). Respiratory complications were frequent (53%) and were associated to longer hospital stay: 83.1 (61.3) and 45.3 (28.1) days in patients with and without respiratory complications (p < 0.001). -

Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study

SPINE Volume 31, Number 4, pp 451–458 ©2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study Allan D. Levi, MD, PhD,* R. John Hurlbert, MD, PhD,† Paul Anderson, MD,‡ Michael Fehlings, MD, PhD,§ Raj Rampersaud, MD,§ Eric M. Massicotte, MD,§ John C. France, MD, Jean Charles Le Huec, MD, PhD,¶ Rune Hedlund, MD,** and Paul Arnold, MD†† Study Design. A retrospective study was undertaken their neurologic injury. The most common reason for the that evaluated the medical records and imaging studies of missed injury was insufficient imaging studies (58.3%), a subset of patients with spinal injury from large level I while only 33.3% were a result of misread radiographs or trauma centers. 8.3% poor quality radiographs. The incidence of missed Objective. To characterize patients with spinal injuries injuries resulting in neurologic injury in patients with who had neurologic deterioration due to unrecognized spine fractures or strains was 0.21%, and the incidence as instability. a percentage of all trauma patients evaluated was 0.025%. Summary of Background Data. Controversy exists re- Conclusions. This multicenter study establishes that garding the most appropriate imaging studies required to missed spinal injuries resulting in a neurologic deficit “clear” the spine in patients suspected of having a spinal continue to occur in major trauma centers despite the column injury. Although most bony and/or ligamentous presence of experienced personnel and sophisticated im- spine injuries are detected early, an occasional patient aging techniques. Older age, high impact accidents, and has an occult injury, which is not detected, and a poten- patients with insufficient imaging are at highest risk. -

Update on Critical Care for Acute Spinal Cord Injury in the Setting of Polytrauma

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 43 (5):E19, 2017 Update on critical care for acute spinal cord injury in the setting of polytrauma *John K. Yue, BA,1,2 Ethan A. Winkler, MD, PhD,1,2 Jonathan W. Rick, BS,1,2 Hansen Deng, BA,1,2 Carlene P. Partow, BS,1,2 Pavan S. Upadhyayula, BA,3 Harjus S. Birk, MD,3 Andrew K. Chan, MD,1,2 and Sanjay S. Dhall, MD1,2 1Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Francisco; 2Brain and Spinal Injury Center, Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, San Francisco; and 3Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Diego, California Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) often occurs in patients with concurrent traumatic injuries in other body systems. These patients with polytrauma pose unique challenges to clinicians. The current review evaluates existing guidelines and updates the evidence for prehospital transport, immobilization, initial resuscitation, critical care, hemodynamic stabil- ity, diagnostic imaging, surgical techniques, and timing appropriate for the patient with SCI who has multisystem trauma. Initial management should be systematic, with focus on spinal immobilization, timely transport, and optimizing perfusion to the spinal cord. There is general evidence for the maintenance of mean arterial pressure of > 85 mm Hg during imme- diate and acute care to optimize neurological outcome; however, the selection of vasopressor type and duration should be judicious, with considerations for level of injury and risks of increased cardiogenic complications in the elderly. Level II recommendations exist for early decompression, and additional time points of neurological assessment within the first 24 hours and during acute care are warranted to determine the temporality of benefits attributable to early surgery. -

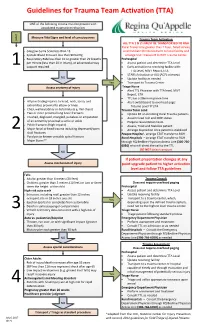

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

18.2 1 Degloving Injuries

18.2 1 Degloving Injuries R. Reid Hanson, DVM, Diplomate ACVS and ACVECC Introduction Management of Degloving Injuries Healing of Distal Limb Wounds Wound Preparation and Evaluation Vascularity and Granulation Surgical Management Wound Contraction Open Wound Management Second Intention Healing Immobilization of the Wound Sequestra Formation Management of Sequestra Impediments to Wound Healing Skin Grafting Healing of Degloving Wounds Conclusion Complications Associated with Denuded References Bone Methods to Stimulate the Growth of Granulation Tissue Introduction Horses are subject to trauma in relation to their locale, use, and character. Wire fences, sheet metal, or other sharp objects in the environment, as well as entrapment between two immovable objects or during transport, are often the cause of injury. The wounds are commonly associated with extensive soft tissue loss, crush injury, and harsh contamination, which necessitate open wound management and second intention healing. One of the most difficultof these wounds to heal is the degloving injury that exposes bone by avulsion of the skin and subcutaneous tissues overlying it. Exposed bone is defined as bone denuded of periosteum, which in an open wound can delay second inten- tion healing indirectly and directly.' The rigid nature of bone indirectly inhibits contraction of granulation tissue and can prolong the inflammatory phase of repair.' Prolonged periods may be required for extensive wounds of the distal extremity with denuded bone and tendon to become covered with a healthy, uniform bed of granu- lation tiss~e.~Desiccation of the superficial layers of exposed bone can lead to sequestrum formation, which is one of the most common causes for delayed healing of wounds of the distal limb of horse^.^ Rapid coverage of exposed bone with granulation tissue can decrease healing time and prevent desiccation of exposed bone and subsequent sequestrum formation. -

Pediatric Shock

REVIEW Pediatric shock Usha Sethuraman† & Pediatric shock accounts for significant mortality and morbidity worldwide, but remains Nirmala Bhaya incompletely understood in many ways, even today. Despite varied etiologies, the end result †Author for correspondence of pediatric shock is a state of energy failure and inadequate supply to meet the metabolic Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Division of demands of the body. Although the mortality rate of septic shock is decreasing, the severity Emergency Medicine, is on the rise. Changing epidemiology due to effective eradication programs has brought in Carman and Ann Adams new microorganisms. In the past, adult criteria had been used for the diagnosis and Department of Pediatrics, 3901 Beaubien Boulevard, management of septic shock in pediatrics. These have been modified in recent times to suit Detroit, MI 48201, USA the pediatric and neonatal population. In this article we review the pathophysiology, Tel.: +1 313 745 5260 epidemiology and recent guidelines in the management of pediatric shock. Fax: +1 313 993 7166 [email protected] Shock is an acute syndrome in which the circu- to generate ATP. It is postulated that in the face of latory system is unable to provide adequate oxy- prolonged systemic inflammatory insult, overpro- gen and nutrients to meet the metabolic duction of cytokines, nitric oxide and other medi- demands of vital organs [1]. Due to the inade- ators, and in the face of hypoxia and tissue quate ATP production to support function, the hypoperfusion, the body responds by turning off cell reverts to anaerobic metabolism, causing the most energy-consuming biophysiological acute energy failure [2]. -

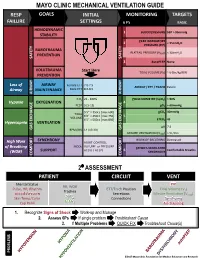

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain.