S1

- Volumen 71

- Mayo 2015

Revista Española de Clínica e Investigación

Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de

Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría

SEINAP

Sumario

XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD ESPAñOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIáTRICOS

Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015

MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MONITORIZACIÓN?

Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación

de oxígeno? P . G arcía Soler

Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53

Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP

Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín

MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO CRONIFICADO EN UCIP

Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP.

Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta

Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero

138

47 60 64 68 72

CHARLA-COLOQUIO

SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE?

Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada.

M. T . A lonso

Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados

Intensivos Pediátricos. P . d e la Oliva Senovilla

La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas.

J.C. de Carlos Vicente

13 20

Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira

Iglesias

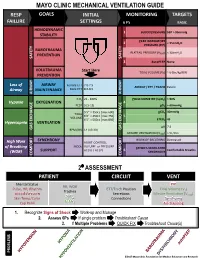

El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas

MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD DE LA SECIP

23

26

Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. La comunicación efectiva. E. Pérez Estévez Presentación de la propuesta del grupo de trabajo de seguridad sobre los indicadores de calidad de la SECIP.

A.A. Hernández Borges

MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, UN RETO PARA ENFERMERÍA

Hermanos… los grandes olvidados. M.J. Muñoz Blanco ¿Qué opinan los padres? C. Arcos von Haartman

76 80

29

33

Análisis reactivo de los eventos centinelas en UCIP.

M. Fernández Elías

MESA REDONDA: LA REALIDAD DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN EN ENFERMERÍA

La importancia de la investigación enfermera.

P. L una Castaño

82 85 88

MESA REDONDA: ¿QUÉ HAY DE NUEVO EN…?

Diagnóstico y tratamiento con antibióticos nebulizados en la infección respiratoria relacionada con ventilación mecánica (VM). M. Balaguer Gargallo

¿Cómo empezar a investigar? M. Cebrián Batalla

COMUNICACIONES ORALES

37 42

Aspectos relevantes del daño medular agudo. M. Herrera López Qué hay de nuevo en la estabilización y transporte del niño y neonato crítico. K.B. Brandstrup

Revista Española de Clínica e Investigación

Mayo 2015

Volumen 71 - Suplemento 1

DIRECTOR

Manuel Hernández Rodríguez

SECRETARIO DE REDACCIÓN

Arturo Muñoz Villa

EDITORES PARA EL EXTRANJERO

A.E. Cedrato (Buenos Aires) N. Cordeiro Ferreira (Lisboa) J. Salazar de Sousa (Lisboa) J.F. Sotos (Columbus)

CONSEJO DE REDACCIÓN

Milagros Alonso Blanco Juan M. Aparicio Meix Julio Ardura Fernández Josep Argemí Renom

Javier González de Dios Antonio Jurado Ortiz Luis Madero López Serafín Málaga Guerrero Antonio Martínez Valverde Federico Martinón Sánchez José Mª Martinón Sánchez Luis A. Moreno Aznar Manuel Moro Serrano Manuel Nieto Barrera José Luis Olivares López Alfonso Olivé Pérez José Mª Pérez-González Juan Luis Pérez Navero Jesús Pérez Rodríguez

Jesús Argente Oliver Javier Arístegui Fernández Raquel Barrio Castellanos Emilio Blesa Sánchez Josep Boix i Ochoa Luis Boné Sandoval

CONSEJO EDITORIAL Presidente

José Peña Guitián

Augusto Borderas Gaztambide Juan Brines Solanes

Vocales

Cristina Camarero Salces Ramón Cañete Estrada Antonio Carrascosa Lezcano Enrique Casado de Frías Juan Casado Flores

Alfredo Blanco Quirós Emilio Borrajo Guadarrama Manuel Bueno Sánchez Cipriano Canosa Martínez Juan José Cardesa García Eduardo Domenech Martínez Miguel García Fuentes Manuel Hernández Rodríguez Rafael Jiménez González Juan Antonio Molina Font Manuel Moya Benavent José Quero Jiménez

Joaquín Plaza Montero Manuel Pombo Arias Antonio Queizán de la Fuente Justino Rodríguez-Alarcón Gómez Mercedes Ruiz Moreno Santiago Ruiz Company Francisco J. Ruza Tarrio Valentín Salazar Villalobos Pablo Sanjurjo Crespo Antonio Sarría Chueca Juan Antonio Tovar Larrucea Adolfo Valls i Soler

Manuel Castro Gago Manuel Cobo Barroso Manuel Crespo Hernández Manuel Cruz Hernández Alfonso Delgado Rubio Ángel Ferrández Longás José Ferris Tortajada Manuel Fontoira Suris Jesús Fleta Zaragozano José Mª Fraga Bermúdez Alfredo García-Alix Pérez José González Hachero

Rafael Tojo Sierra Alberto Valls Sánchez de la Puerta Ignacio Villa Elízaga

José Antonio Velasco Collazo Juan Carlos Vitoria Cormenzana

© 2015 ERGON

Periodicidad

Arboleda, 1. 28221 Majadahonda http://www.ergon.es

6 números al año

Suscripción anual

Profesionales 68,97 e; Instituciones: 114,58 e; Extranjero 125,19 e; MIR y estudiantes 58,35 e; Canarias profesionales: 66,32 e.

Soporte Válido: 111-R-CM ISSN 0034-947X Depósito Legal Z. 27-1958 Impreso en España

Suscripciones

ERGON. Tel. 91 636 29 37. Fax 91 636 29 31. [email protected]

Reservados todos los derechos. El contenido de la presente publicación no puede reproducirse o transmitirse por ningún procedimiento electrónico o mecánico, incluyendo fotocopia, grabación magnética o cualquier almacenamiento de información y sistema de recuperación, sin el previo permiso escrito del editor.

Correspondencia Científica

ERGON. Revista Española de Pediatría. Plaça Josep Pallach, 12. 08035 Barcelona [email protected]

Revista Española de Clínica e Investigación

Mayo 2015

Volumen 71 - Suplemento 1

Sumario

MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MONITORIZACIÓN?

Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación de oxígeno?

P. G arcía Soler

MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO

1

38

CRONIFICADO EN UCIP

47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en

UCIP

Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta

Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia

S. Mencía Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP

53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla?

M.A. García Teresa

Avances en neuromonitorización

B. Cabeza Martín

60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto?

J.M. García Piñero

SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE?

CHARLA-COLOQUIO

64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas

J.C. de Carlos Vicente

13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada

M. T . A lonso

20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados

Intensivos Pediátricos

68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: experiencia del intensivista de adultos

- J.C. Figueira Iglesias

- P. d e la Oliva Senovilla

72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto para el intensivista pediátrico

E. Álvarez Rojas

MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD DE LA SECIP

23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. La comunicación efectiva

MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, UN RETO PARA ENFERMERÍA

E. Pérez Estévez

26 Presentación de la propuesta del grupo de trabajo de seguridad sobre los indicadores de calidad de la SECIP

76 Hermanos… los grandes olvidados

M.J. Muñoz Blanco

80 ¿Qué opinan los padres?

A.A. Hernández Borges

C. Arcos von Haartman

29 Análisis reactivo de los eventos centinelas en UCIP

M. Fernández Elías

MESA REDONDA: LA REALIDAD DE LA INVESTIGACIÓN EN ENFERMERÍA

MESA REDONDA: ¿QUÉ HAY DE NUEVO EN…?

33 Diagnóstico y tratamiento con antibióticos nebulizados en la infección respiratoria relacionada con ventilación mecánica (VM)

82 La importancia de la investigación enfermera

P. L una Castaño

85 ¿Cómo empezar a investigar?

M. Cebrián Batalla

M. Balaguer Gargallo

37 Aspectos relevantes del daño medular agudo

- 88

- COMUNICACIONES ORALES

M. Herrera López

42 Qué hay de nuevo en la estabilización y transporte del niño y neonato crítico

K.B. Brandstrup

Revista Española de Clínica e Investigación

May 2015

Volume 71 - Supplement 1

Contents

ROUND TABLE: WHERE ARE WE HEADED IN MONITORING?

ROUND TABLE: THE CHRONIC SEVERE PATIENT IN PICU

1

38

Pulsioxymetry monitorization: only oxygen saturation?

47 Nutrition in the long stay critical patient in the PICU

Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta

P. G arcía Soler

53 Tracheostomy, when should it be performed?

Advances in monitoring of sedoanalgesia

S. Mencía Bartolomé and Sedoanalgesia group of the SECIP

M.A. García Teresa

60 Nursing cares, is this a challenge?

J.M. García Piñero

Advances in neuromonitoring

B. Cabeza Martín

LECTURE-DISCUSSION

64 Training in the preparation of the Spanish PICUs against the risk of infectious epidemics

J.C. de Carlos Vicente

UPDATE SESSION: IS FLUID THERAPY BENEFICIAL FOR MY PATIENT?

13 Fluid overload and associated morbidity-mortality

68 Lessons learning during the Ebola crisis: experience

of the adult intensive care physicians

J.C. Figueira Iglesias

M. T . A lonso

20 Strategies of rational fluid therapy in Pediatric

Intensive Cares

72 The child with Ebola virus disease: a new challenger

of the pediatric intensive care physician

E. Álvarez Rojas

P. d e la Oliva Senovilla

ROUND TABLE: QUALITY INDICATORS OF THE SECIP

ROUND TABLE: 24-HOUR OPEN PICU, A

CHALLENGE FOR NURSING

23 Evolution of the safety culture in the PICU. Effective communication

E. Pérez Estévez

76 Siblings… the greatly forgotten

M.J. Muñoz Blanco

26 Presentation of the proposal of the safety work group on SECIP quality indicators

80 What do the parents think?

C. Arcos von Haartman

A.A. Hernández Borges

29 Reactive analysis of the sentinel events in the PICU

ROUND TABLE: REALITY OF RESEARCH IN NURSING

M. Fernández Elías

82 The importance of nursing research

ROUND TABLE: WHAT IS NEW IN ....?

33 Diagnosis and treatment with nebulized antibiotics in respiratory infection related with mechanical ventilation (MV)

P. L una Castaño

85 How to begin investigating?

M. Cebrián Batalla

M. Balaguer Gargallo

- 88

- ORAL COMMUNICATIONS

37 Important aspects of severe bone marrow damage

M. Herrera López

42 What is new in stabilization and transporting the critical child and newborn?

K.B. Brandstrup

MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MONITORIZACIÓN?

Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación de oxígeno?

P. García Soler

UGC Cuidados Críticos y Urgencias Pediátricas. HRU Materno Infantil de Málaga.

La pulsioximetría ha demostrado ser una herramienta útil en la monitorización del sistema respiratorio desde su introducción hace unos 30 años y su uso está bien establecido en los entornos de cuidados críticos, anestesiología y servicios de urgencias.

Desde sus orígenes, se han conseguido avances tecnológicos significativos en los dispositivos comercialmente disponibles. Dentro de estos avances se incluyen el análisis extendido de la onda fotopletismográfica (FPG), el uso de luz de múltiples longitudes de onda para cuantificar la metaHb, COHb y concentración de Hb total en sangre, así como el uso de procesos electrónicos que mejoran el procesamiento de la señal en condiciones de baja relación señal/ruido. Estos avances han abierto un abanico de nuevas posibilidades para su uso en la clínica que pueden tener un impacto en la monitorización y manejo de nuestros pacientes. son registradas y la SaO2 se deriva de la división de ambas proporciones (R), definida como: (AC/DC)1/(AC/DC)2

Por otra parte, cabe mencionar que estos fundamentos físicos (basados en la ley de Beer-Lambert, según la cual la intensidad de luz transmitida por un cuerpo es igual a la intensidad de luz que incide multiplicada por una variable específica) no son estrictamente aplicables en el medio clínico. Los instrumentos de pulsioximetría requieren de correcciones empíricas a las que se llega mediante aplicación de la técnica a grandes poblaciones de individuos sanos, lo que permite conseguir un algoritmo mediante el cual el procesador interpreta la información obtenida a través de la medición.

Al aplicarlo a través de una parte del cuerpo relativamente translúcida y con buen flujo sanguíneo arterial (p. ej.: los dedos de la mano o del pie, el lóbulo de la oreja), la luz de cada longitud de onda es absorbida por la oxihemoglobina y desoxihemoglobina, reflejando en el fotodetector la diferencia. La mayor parte de la luz es absorbida por el tejido conectivo, piel, hueso y sangre venosa en una cantidad constante, produciéndose un pequeño incremento de esta absorción en la sangre arterial con cada latido, lo que significa que es necesaria la presencia de pulso arterial para que el aparato reconozca alguna señal. Mediante la comparación de la luz que absorbe durante la onda pulsátil con respecto a la absorción basal, se calcula el porcentaje de oxihemoglobina. Sólo se mide la absorción neta durante una onda de pulso, lo que minimiza la influencia de tejidos, venas y capilares en el resultado.

El cociente de luz roja a infrarroja que pasa a través del sitio de medición y que recibe el detector del oxímetro depende del porcentaje de hemoglobina oxigenada frente a desoxigenada por donde pasa la luz. El porcentaje de saturación de oxígeno así calculado se le conoce con el porcentaje de SpO2.

FUNDAMENTOS Y TÉCNICA DE LA PULSIOXIMETRÍA CONVENCIONAL

La pulsioximetría es un método no invasivo que permite la rápida medición de la saturación de oxígeno de la hemoglobina (Hb) en sangre arterial en base a las propiedades espectrofotométricas de la misma. Un pulsioxímetro consta de un transductor con dos piezas: un emisor de luz y un fotodetector. El emisor transmite luz a dos longitudes de onda –40 nm (infrarroja) y 660 nm (roja)– que son características respectivamente de la oxihemoglobina y la hemoglobina reducida. La luz es absorbida principalmente por la hemoglobina, pero también por otros cromóforos como la melanina y la mioglobina. La sangre venosa, con menor contenido de oxiHb, también absorbe esta luz. La necesidad de aislar la contribución de la Hb en sangre arterial ha llevado al desarrollo de la pulsioximetría.

La pulsioximetría está basada en la fotopletismografía (FPG), la medición del incremento de absorción de luz debido al aumento sistólico del volumen sanguíneo arterial. La intensidad de la luz transmitida desciende durante la sístole, cuando la sangre es eyectada desde el ventrículo izquierdo al árbol vascular, incrementándose el volumen sanguíneo arterial periférico. Los valores máximo y mínimo de la FPG del pulso reflejan la radiación de luz transmitida a través de los tejidos cuando el volumen de sangre es mínimo o máximo respectivamente. La amplitud de la FPG está relacionada con la absorción de la luz en el incremento del volumen sanguíneo arterial durante la sístole. La medición de la FPG en cada longitud de onda permite la estimación de la contribución de la sangre arterial a la absorción total de la luz, asumiendo que la señal de FPG refleja los cambios en el volumen sanguíneo arterial.

La amplitud de la señal de FPG (AC) dividido entre su línea de base

(DC) se relaciona con la máxima variación en volumen sanguíneo durante la sístole. Para medir la SaO2, las curvas de FPG en dichas longitudes de onda

AVANCES EN LA PULSIOXIMETRÍA Análisis de la morfología de la onda fotopletismográfica

El análisis de la onda fotopletismográfica se basa en la señal proporcional a la absorción de la luz infrarroja entre el emisor y el fotodetector. La señal original se genera a partir del detector. La mayoría de pulsioxímetros procesan esta señal antes de ser mostrada en el dispositivo. La onda FPG tiene dos componentes, frecuentemente denominados DC y AC. El componente DC corresponde a la parte no pulsátil de la señal y es inversamente proporcional a la absorción de la luz y a la dispersión por tejidos no pulsátiles de la región donde se coloca el sensor, incluyendo la sangre no pulsátil (arterial y venosa). La zona AC es el componente pulsátil de la señal, asumiéndose que representa a la sangre arterial de la circulación.

La FPG mide los cambios en volumen que se producen en la región estudiada, habitualmente el pulpejo del dedo. A mayor volumen sanguíneo en el dedo (vasodilatación), mayor cantidad de luz es absorbida, menor cantidad de luz es transmitida y por tanto la corriente detectada por el fotodetector es menor. Así, durante la sístole, la cantidad de luz detectada es menor que

Rev esp pediatR 2015; 71(Supl. 1): 1-2

1

Vol. 71 Supl. 1, 2015

Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación de oxígeno?

Amplitud

Fin diástole Sístole

AC

DC

Tiempo

t

0

FIGURA 2. Representación gráfica de los componentes de la onda FPG.

FIGURA 1. Representación gráfica de la señal infrarroja detectada por el pulsioxímetro.

Recientemente se han desarrollado pulsioxímetros que emiten luz a di-

ferentes longitudes de onda para analizar distintos tipos de Hb. Utilizando ocho o más longitudes de onda, este dispositivo puede mostrar de manera no invasiva y continua la concentración de carboxihemoglobina, metahemoglobina y la hemoglobina total.

La monitorización de estos tipos de hemoglobina tiene gran utilidad en el manejo de intoxicaciones en el área de Urgencias, en anestesia con agentes inhalados y en el seguimiento del paciente en tratamiento con nitroprusiato, entre otras aplicaciones.

La monitorización continua no invasiva de la concentración total de hemoglobina ha demostrado ser de utilidad en el manejo de pacientes con riesgo de sangrado, tanto en unidades de cuidados intensivos como durante el acto quirúrgico. El principal inconveniente de este método es la dependencia de una aceptable calidad de la señal que puede estar comprometida en pacientes en situación de bajo gasto, anemias graves y utilización de fármacos vasopresores. lo que ocurre en diástole y la señal FPG originalmente registrada se asemeja a una imagen en espejo de la presión arterial. Para que esta imagen sea más fácilmente interpretada por los clínicos, la mayoría de dispositivos la invierten. Además la onda es habitualmente autoescalada para ajustarse a la pantalla. Como resultado, la información fisiológica que ofrece la morfología de la onda FPG se pierde.

Los cambios en los componentes AC y DC se han relacionado con el tono vasomotor. El componente DC también está influenciado por la respiración y puede ofrecer información acerca del estado de precarga del paciente.

Una variable que se deriva del análisis de la onda FPG es el índice de perfusión (IP), definido como AC/DC x 100%, que representa la razón entre el flujo de sangre pulsátil y el no pulsátil de los tejidos periféricos. En términos generales el IP refleja el tono vasomotor: valores bajos de IP sugieren vasoconstricción o hipovolemia grave, mientras que IP elevados orientan hacia vasodilatación. El IP se modifica con los cambios en la temperatura de la región estudiada, el uso de vasoconstrictores, el tono simpático (dolor, ansiedad) y volumen sistólico. El IP ha sido utilizado para la monitorización de la eficacia de la anestesia regional y epidural, dado que el bloqueo simpá- tico se acompaña de vasodilatación.

Otra variable que se deriva del análisis de la onda FPG es el índice de variabilidad pletismográfica (IVP), un parámetro relativamente nuevo que sólo lo ofrece un dispositivo actualmente. El IVP cuantifica la variabilidad de la onda FPG debida a la respiración y por tanto puede ser una medida del estado de volumen intravascular. Se define como (IPmáx - IPmín)/IPmáx x 100%.

Los distintos marcadores predictores dinámicos de respuesta a fluidos se basan en la interacción cardiopulmonar en pacientes ventilados mecánicamente. Durante la inspiración, el aumento de la presión intratorácica induce un descenso en el retorno venoso ventricular derecho. Este fenómeno lleva a un descenso del volumen sistólico que se transmite al ventrículo izquierdo. Lo inverso ocurre durante la espiración. Estos fenómenos son responsables de los cambios en el volumen sistólico y pueden ser detectados en la onda de presión arterial. Valores de IVP >14% se han asociado a necesidad de volumen en pacientes adultos en ventilación mecánica. En niños no existen estudios que validen fielmente este punto de corte, aunque se han sugerido valores cercanos al 15%.