Autonomic Dysreflexia a Life Threatening Emergency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suplento1 Volumen 71 En

S1 Volumen 71 Mayo 2015 Revista Española de Vol. 71 Supl. 1 • Mayo 2015 Vol. Clínica e Investigación Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de SEINAP Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría Sumario XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD espaÑOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIÁTRICOS Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015 MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO MONITORIZACIÓN? CRONIFICADO EN UCIP 1 Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación 47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP. de oxígeno? P. García Soler Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta 3 Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP 60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero 8 Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín CHARLA-COLOQUIO SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA 64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE? españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas. 13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada. J.C. de Carlos Vicente M.T. Alonso 68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: 20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira Intensivos Pediátricos. P. de la Oliva Senovilla Iglesias 72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas DE LA SECIP 23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, La comunicación efectiva. -

Pediatric Shock

REVIEW Pediatric shock Usha Sethuraman† & Pediatric shock accounts for significant mortality and morbidity worldwide, but remains Nirmala Bhaya incompletely understood in many ways, even today. Despite varied etiologies, the end result †Author for correspondence of pediatric shock is a state of energy failure and inadequate supply to meet the metabolic Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Division of demands of the body. Although the mortality rate of septic shock is decreasing, the severity Emergency Medicine, is on the rise. Changing epidemiology due to effective eradication programs has brought in Carman and Ann Adams new microorganisms. In the past, adult criteria had been used for the diagnosis and Department of Pediatrics, 3901 Beaubien Boulevard, management of septic shock in pediatrics. These have been modified in recent times to suit Detroit, MI 48201, USA the pediatric and neonatal population. In this article we review the pathophysiology, Tel.: +1 313 745 5260 epidemiology and recent guidelines in the management of pediatric shock. Fax: +1 313 993 7166 [email protected] Shock is an acute syndrome in which the circu- to generate ATP. It is postulated that in the face of latory system is unable to provide adequate oxy- prolonged systemic inflammatory insult, overpro- gen and nutrients to meet the metabolic duction of cytokines, nitric oxide and other medi- demands of vital organs [1]. Due to the inade- ators, and in the face of hypoxia and tissue quate ATP production to support function, the hypoperfusion, the body responds by turning off cell reverts to anaerobic metabolism, causing the most energy-consuming biophysiological acute energy failure [2]. -

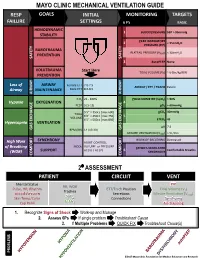

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Hypothesis Spinal Shock and `Brain Death': Somatic Pathophysiological

Spinal Cord (1999) 37, 313 ± 324 ã 1999 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/sc Hypothesis Spinal shock and `brain death': Somatic pathophysiological equivalence and implications for the integrative-unity rationale DA Shewmon*,1 1Pediatric Neurology, UCLA Medical School, Los Angeles, California, USA The somatic pathophysiology of high spinal cord injury (SCI) not only is of interest in itself but also sheds light on one of the several rationales proposed for equating `brain death' (BD) with death, namely that the brain confers integrative unity upon the body, which would otherwise constitute a mere conglomeration of cells and tissues. Insofar as the neuropathology of BD includes infarction down to the foramen magnum, the somatic pathophysiology of BD should resemble that of cervico-medullary junction transection plus vagotomy. The endocrinologic aspects can be made comparable either by focusing on BD patients without diabetes insipidus or by supposing the victim of high SCI to have pre-existing therapeutically compensated diabetes insipidus. The respective literatures on intensive care for BD organ donors and high SCI corroborate that the two conditions are somatically virtually identical. If SCI victims are alive at the level of the `organism as a whole', then so must be BD patients (the only signi®cant dierence being consciousness). Comparison with SCI leads to the conclusion that if BD is to be equated with death, a more coherent reason must be adduced than that the body as a biological organism is dead. Keywords: brain death; spinal cord injury; spinal shock; integrative functions; somatic integrative unity; organism as a whole Introduction Spinal shock is a transient functional depression of the society; its legal de®nition is culturally relative, and structurally intact cord below a lesion, following acute most modern societies happen to have chosen to spinal cord injury (SCI). -

Polytrauma Shock • Trauma Related Costs in the U.S

POLYTRAUMA SHOCK • TRAUMA RELATED COSTS IN THE U.S. 400 BILLION $ • 3.8 MILLION DEATHS PER YEAR • THE LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH IN PERSONS AGED 1 TO 45 IN THE MOST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES • TRIMODAL DEATH DISTRIBUTION 1. SECONDS, MINS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO BRAIN, C. SPINE, LARGE VESSEL INJ. 2. 1-2 HOURS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO EPIDURAL HAEMATOMAS, BLEEDINGS GOLDEN HOUR 3. SEVERAL DAYS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO M.O.F., SEPSIS TRIMODAL DEATH DISTRIBUTION 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% HOURS 0 1 2 3 4 WEEKS 1 2 3 4 TRIMODAL BIMODAL? THE SECOND GROUP IS DECREASING DUE TO PROPER TREATMENT GOLDEN HOUR NOT ONLY SALVAGEABILITY BUT MANY LATE PROBLEMS (SIRS, MOF) ARE THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE PRIMARY HYPOXIA AND MEDIATOR RELEASE SILVER DAY BRONZE WEEK PLATINA 10 MIN DEFINITION OF POLYTRAUMA A. INJURY TO ONE OR MORE BODY REGIONS OR ORGANS OF WHICH ONE, OR THEIR COMBINATIONS IS LIFE THREATENING B. INJURY TO MORE BODY REGIONS FOLLOWING WHICH, DURING TREATMENT, WE HAVE TO MAKE COMPROMISES C. INJURY TO HOLLOW ORGANS + INJURY TO EXTREMITIES D. INJURY DEFINED BY A SCORING SYSTEM TRAUMA SCORE NUMBER OF BREATHS PER MIN 0-4 INTENSITY OF BREATHING 0-1 SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE 0-4 CAPILLARY REFILL 0-2 GLASGOW COMA SCALE 0-5 POSSIBILITY FOR SURVIVAL 16+ <2 99% 0% GLASGOW COMA SCALE EYE OPENING SPONTANEOUS 4 TO SPEECH 3 TO PAIN 2 NONE 1 BEST MOTOR RESPONSE OBEYS COMMANDS 6 LOCALIZES PAIN 5 NORMAL FLEXION 4 ABNORMAL FLEXION 3 EXTENSION 2 NONE 1 VERBAL RESPONSE ORIENTED 5 CONFUSED CONVERS. 4 WORDS 3 SOUNDS 2 NOTHING 1 ABBREVIATED INJURY SCALE (ISS) 1 MILD 2 MEDIUM 3 SEVERE 4 VERY -

A Systematic Review of the Evidence Supporting a Role for Vasopressor Support in Acute SCI

Spinal Cord (2010) 48, 356–362 & 2010 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/sc REVIEW A systematic review of the evidence supporting a role for vasopressor support in acute SCI A Ploumis1,2, N Yadlapalli2, MG Fehlings3, BK Kwon4 and AR Vaccaro2 1Division of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Department of Surgery, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece; 2Department of Orthopaedics, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 3Division of Neurosurgery and Spinal Program, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and 4Department of Orthopaedics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Study design: A systematic review of clinical and preclinical literature. Objective: To critically evaluate the evidence supporting a role for vasopressor support in the management of acute spinal cord injury and to provide updated recommendations regarding the appropriate clinical application of this therapeutic modality. Background: Only few clinical studies exist examining the role of arterial pressure and vasopressors in the context of spinal cord trauma. Methods: Medical literature was searched from the earlier available date to July 2009 and 32 articles (animal and human literature) answering the following four questions were studied: what patient groups benefit from vasopressor support, which is the optimal hypertensive drug regimen, which is the optimal duration of the treatment and which is the optimal arterial blood pressure. Outcome measures used were the incidence of patients needing vasopressors, the increase of arterial blood pressure and neurologic improvement. Results: Patients with complete cervical cord injuries required vasopressors more frequently than either incomplete injuries or thoracic/lumbar cord injuries (Po0.001). -

Neurogenic Shock

NEUROGENIC SHOCK Introduction Neurogenic shock is a form of circulatory shock that may occur with severe injury to the upper spinal cord. It should not be confused with spinal shock, which refers to the initial flaccid muscle paralysis and loss of reflexes seen after spinal cord injury. Pathology Neurogenic shock results from severe spinal cord injury of the upper segments. This is usually at or above the level of T4, as the sympathetic cardiac nerves arise at the level of T1-4. Spinal cord lesions below this level do not result in neurogenic shock. The cause of the circulatory compromise is due to disruption of the descending sympathetic nervous supply of the spinal cord, hence a hallmark of the condition will be hypotension together with a bradycardia. Hypotension results from: ● Bradycardia, (or at least a failure of a tachycardic response to a fall in blood pressure). ● Reduced myocardial contractility ● Peripheral vasodilation. Note that isolated intracranial injuries to the CNS do not cause circulatory shock, and if this is present in such cases then other causes of shock need to be pursued. Clinical Features Patients with neurogenic shock usually have significant associated thoracic trauma and hypovolemic shock may co-exist with neurogenic shock. Hypovolemic shock is common, and immediately life-threatening, whilst neurogenic shock is uncommon, and rarely immediately life-threatening, in isolation. In the first instance any trauma patient who has hypotension must therefore be assumed to have hypovolemia until proven otherwise. The diagnosis of neurogenic shock must necessarily be one of exclusion. The classic description of neurogenic shock is hypotension without tachycardia or peripheral vasoconstriction. -

System Specific Trauma

MODULE 3 System Specific Trauma | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 1 www.who.int/surgery OBJECTIVES FOR MODULE 3 To learn specific management strategies for trauma • Head • Spine and spinal cord • Chest • Abdomen • Female genitalia • Musculoskeletal system | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 2 www.who.int/surgery Head Injury | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 3 www.who.int/surgery HEAD INJURY • Altered level of consciousness is a hallmark of acute cerebral trauma • Never assume that substances (alcohol or drugs) are causes of drowsiness • Frequent clinical mistakes: – Incomplete ABC's, priority management – Incomplete primary, secondary surveys – Incomplete baseline neurologic examination – No reassessment of neurologic status | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 4 www.who.int/surgery HEAD INJURY Basal skull fractures – Periorbital ecchymosis (racoon eyes) – Mastoid ecchymosis (Battle's sign) – Cerebrospinal fluid leak from ears or nose Depressed skull fracture – Fragments of skull may penetrate dura, brain Cerebral concussion – Variable temporary altered consciousness | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 5 www.who.int/surgery HEAD INJURY Intracerebral hematoma – Caused by acute injury or delayed, progressive bleeding originating from contusion Clinical features of increased intracranial pressure: – Decreased level of consciousness – Bradycardia – Unequal or dilated pupils – Seizures – Focal neurologic deficit | Emergency and Essential -

Trauma: Spinal Cord Injury

Trauma: Spinal Cord Injury a, a,b Matthew J. Eckert, MD *, Matthew J. Martin, MD KEYWORDS Spine Spine trauma Spinal cord injury Spinal cord syndromes Spinal shock Spine immobilization KEY POINTS Hypotension following trauma should be considered secondary to hemorrhage until proven otherwise, even in patients with early suspicion of spinal injury. Neurogenic shock and spinal shock are separate, important entities that must be understood. Hypoxia and hypotension should be aggressively corrected because they lead to second- ary spinal cord injury, analogous to traumatic brain injury. Critical care support of multiple organ systems is frequently required early after injury. Early spinal decompression may lead to improved neurologic outcomes in select spinal cord injuries, and prompt consultation with spine surgeons is recommended. Computed tomography (CT) is the gold-standard screening study for evaluation of the spine after trauma and has significantly greater sensitivity and specificity compared with plain radiographs. High-quality CT imaging without evidence of cervical spine injury may be adequate for removal of the cervical immobilization collar in obtunded patients. INTRODUCTION Traumatic spine and spinal cord injury (SCI) occurred in roughly 17,000 US citizens in 2016, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 280,000 injured persons.1 Although the injury has historically been a disease of younger adult men, a progressive increase in SCI incidence among the elderly has been reported over the last few de- cades.2 Upwards of 70% of SCI patients suffer multiple injuries concomitant with spi- nal cord trauma, contributing to the high rates of associated complications during the acute and long-term phases of care.3 SCI is associated with significant reductions in life expectancy across the spectrum of injury and age at time of insult.1 Patients who survive the initial injury face significant risks of medical complications throughout the rest of their lives. -

Spinal Trauma Guideline

SPINAL TRAUMA GUIDELINE 1. Key messages ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Rapid Reference Guideline .................................................................................................... 3 3. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4 4. Early activation ...................................................................................................................... 5 5. Primary survey ....................................................................................................................... 6 6. Secondary survey ................................................................................................................... 8 7. Planning and communication .............................................................................................. 12 8. Early management ............................................................................................................... 13 9. Retrieval and transfer .......................................................................................................... 16 10. Guideline Implementation ................................................................................................... 16 1. Key messages The Victorian State Trauma System provides support and retrieval services for critically injured patients requiring definitive care, transfer and management. -

Managing Acute Neuromuscular Weakness Neuromuscular Emergencies

Managing Acute Neuromuscular Weakness Neuromuscular Emergencies Approach to an acute, rapidly progressing, generalized lower motor neuron weakness aka Approach to an acutely floppy person Today’s Agenda Practical approach to weakness Focus on specific neuromuscular disorders: Guillain Barre Syndrome Myasthenia Gravis Focusing on crises Weakness is not always neurological Causes of generalized weakness Neurological Non-neurological Upper Motor Neuron Lower Motor Neuron Both UMN and LMN Weakness is not always neurological Causes of generalized weakness Neurological Non-neurological Upper Motor Neuron Lower Motor Neuron Both UMN and LMN Non-neurological Hypoglycemia + Electrolyte abnormalities: K , Ca, Mg, PO4 Sepsis Acute coronary syndrome Cardiopulmonary disease Adrenal insufficiency Anemia Dehydration/hypovolemia Drugs Fibromyalgia/Arthritis Malignancy Depression/conversion disorder Most important Neurological Investigation When the weakness is neurological Causes of generalized weakness Neurological Non-neurological Upper Motor Neuron Lower Motor Neuron Both UMN and LMN Lower motor neuron Upper motor neuron Flaccid Spasticity Decreased tone Increased tone Decreased muscle Increased muscle stretch reflexes stretch reflexes Profound muscle Minimal muscle atrophy atrophy Fasiculations present Fasiculations absent May have sensory May have sensory disturbances disturbances Bilateral UMN weakness Cerebrum Bilateral strokes Parasaggital tumors Diplegic CP Brainstem Midbrain/pons/medulla Spinal cord disease Trauma Infection/Abscess Neoplasm -

Description This Case Study Focuses on the Care of a 58-Year-Old Patient

Description This case study focuses on the care of a 58-year-old patient who sustains a spinal cord injury as the result of an all-terrain vehicle (ATV) collision and subsequently develops neurogenic and spinal shock. Patient assessments, laboratory and diagnostic tests, and nursing interventions during patient care, with a focus on patient management in the critical care setting, are described. Note: This course is delivered with audio narration. Continuing Education Credit This course qualifies for 1.0 contact hours, which can be earned on this course until December 4, 2020. Objectives/Outcomes After completing this case study, the learner will be able to: describe pertinent assessment, laboratory, and diagnostic data to determine priorities for nursing care interventions for the spinal cord–injured patient at risk for neurogenic shock. differentiate neurogenic shock from the mechanisms of hemodynamic instability associated with other major types of shock (hypovolemic, obstructive, and cardiogenic). describe the nursing care management needs of the spinal cord patient with neurogenic shock when complications develop (such as respiratory failure, abdominal compartment syndrome, and end-organ failure), including end-of-life care. Disclosure The authors and planners have disclosed that they have no significant relationship with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article. Contributors Marisa B Buchmann, MSN, RN, CPN Subject Matter Expert Karen Wilkinson, MN, PNP Subject Matter Expert Kate Stout, MSN, RN Clinical Editor Lippincott Professional Development Collection Sherry Ratajczak, MSN, PNP Senior Clinical Editor Tahitia Timmons, MSN, RN-BC, OCN Clinical Editor.