Autonomic Dysreflexia 2Nd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suplento1 Volumen 71 En

S1 Volumen 71 Mayo 2015 Revista Española de Vol. 71 Supl. 1 • Mayo 2015 Vol. Clínica e Investigación Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de SEINAP Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría Sumario XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD espaÑOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIÁTRICOS Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015 MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO MONITORIZACIÓN? CRONIFICADO EN UCIP 1 Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación 47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP. de oxígeno? P. García Soler Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta 3 Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP 60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero 8 Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín CHARLA-COLOQUIO SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA 64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE? españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas. 13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada. J.C. de Carlos Vicente M.T. Alonso 68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: 20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira Intensivos Pediátricos. P. de la Oliva Senovilla Iglesias 72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas DE LA SECIP 23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, La comunicación efectiva. -

A Sign It's Time for BOTOX®

When OAB* due to MS† makes matters worse… A sign it’s time for BOTOX® Ask your patients if they still have leakage or can’t tolerate their current OAB medication *Overactive bladder. †Multiple sclerosis. Indication Detrusor Overactivity Associated With a Neurologic Condition BOTOX® for injection is indicated for the treatment of urinary incontinence due to detrusor overactivity associated with a neurologic condition (eg, SCI, MS) in adults who have an inadequate response to or are intolerant of an anticholinergic medication. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION, INCLUDING BOXED WARNING WARNING: DISTANT SPREAD OF TOXIN EFFECT Postmarketing reports indicate that the effects of BOTOX® and all botulinum toxin products may spread from the area of injection to produce symptoms consistent with botulinum toxin effects. These may include asthenia, generalized muscle weakness, diplopia, ptosis, dysphagia, dysphonia, dysarthria, urinary incontinence, and breathing difficulties. These symptoms have been reported hours to weeks after injection. Swallowing and breathing difficulties can be life threatening, and there have been reports of death. The risk of symptoms is probably greatest in children treated for spasticity, but symptoms can also occur in adults treated for spasticity and other conditions, particularly in those patients who have an underlying condition that would predispose them to these symptoms. In unapproved uses and in approved indications, cases of spread of effect have been reported at doses comparable to those used to treat Cervical Dystonia -

Autonomic Dysreflexia – a Medical Emergency a Guide for Patients

Autonomic Dysreflexia – A Medical Emergency A guide for patients Only applicable to T6 level and above Key Points • Autonomic Dysreflexia (AD) is a medical emergency that occurs due to a rapid rise in blood pressure in response to a harmful or painful stimulus below the level of your Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) • It occurs in people with SCI at T6 and above but has in rare occasions been reported in individuals with SCI as low as T8 • If left untreated your blood pressure can rise to dangerous levels, risking stroke, cardiac problems, seizures, even death • Typically there is a pounding headache as your blood pressure rises. Other symptoms can include redness and sweating above the level of your SCI, slow heart rate, goosebumps, nausea, nasal congestion, blurred vision, shortness of breath and anxiety • Some or all of the symptoms may be present • AD can be triggered by any continuous painful or irritating stimulus below the level of your lesion. The most common causes are related to the bladder or bowel • Relieving the cause of the AD will resolve your AD episode • If the cause cannot be found or treated, medication is required to lower your blood pressure which may require a visit to your nearest emergency department • All people with SCI at T6 and above should carry their Autonomic Dysreflexia Medical Emergency Card at all times • The best treatment for AD is prevention • People at risk of AD often carry an ‘AD Kit’ with them – items useful to resolve AD such as catheters and prescribed medication 1 What is Autonomic Dysreflexia? Autonomic Dysreflexia (AD) is a medical emergency. -

Treatment of Autonomic Dysreflexia for Adults & Adolescents with Spinal

Treatment of Autonomic Dysreflexia for Adults & Adolescents with Spinal Cord Injuries Authors: Dr James Middleton, Director, State Spinal Cord Injury Service, NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation. Dr Kumaran Ramakrishnan, Honorary Fellow, Rehabilitation Studies Unit, Sydney Medical School Northern, The University of Sydney, and Consultant Rehabilitation Physician & Senior Lecturer, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University Malaya. Dr Ian Cameron, Head of the Rehabilitation Studies Unit, Sydney Medical School Northern, The University of Sydney. Reviewed and updated in 2013 by the authors. AGENCY FOR CLINICAL INNOVATION Level 4, Sage Building 67 Albert Avenue Chatswood NSW 2067 PO Box 699 Chatswood NSW 2057 T +61 2 9464 4666 | F +61 2 9464 4728 E [email protected] | www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au Produced by the NSW State Spinal Cord Injury Service. SHPN: (ACI) 140038 ISBN: 978-1-74187-972-8 Further copies of this publication can be obtained from the Agency for Clinical Innovation website at: www.aci.health.nsw.gov.au Disclaimer: Content within this publication was accurate at the time of publication. This work is copyright. It may be reproduced in whole or part for study or training purposes subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. It may not be reproduced for commercial usage or sale. Reproduction for purposes other than those indicated above, requires written permission from the Agency for Clinical Innovation. © Agency for Clinical Innovation 2014 Published: February 2014 HS13-136 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was originally published as a fact sheet for the Rural Spinal Cord Injury Project (RSCIP), a pilot healthcare program for people with a spinal cord injury (SCI) conducted within New South Wales involving the collaboration of Prince Henry & Prince of Wales Hospitals, Royal North Shore Hospital, Royal Rehabilitation Centre Sydney, Spinal Cord Injuries Australia and the Paraplegic & Quadriplegic Association of NSW. -

Robert Jenkinson, MD

8/26/14 LIFE-THREATENING, INTRAOPERATIVE HEMODYNAMIC INSTABILITY IN A QUADRAPLEGIC Robert H. Jenkinson, M.D. Department of Anesthesiology University of Wisconsin Madison, WI Background o 57 year old quadraplegic male, remote C4-C5 spinal injury presenting for cystoscopy. n PMHx: Autonomic dysreflexia, OSA, neurogenic bowel/bladder. n Allergies: Sulfa drugs o Prior history of systolic blood pressure (SBP) near or above 200 mmHg while under GA for cystoscopy on multiple occasions. n Required nitroglycerine infusions. n Stable blood pressure with spinal anesthesia on one prior occasion. Case Description o L4-L5 spinal performed in OR n Intravenous midazolam (2mg) & fentanyl (50 mcg) n Intrathecal hyperbaric bupivacaine (12.5 mg) n Intravenous cefazolin (2g) o On return to supine position: n SBP rapidly decreased from baseline of 140 mmHg to 60 mmHg. n The patient became tachycardic. n Breathing pattern became shallow and bradypneic. n Level of responsiveness quickly decreased. 1 8/26/14 Case Description o Vasopressin and epinephrine boluses given. o Trachea intubated. Intra- arterial BP monitoring & central venous access established. § Vasopressin & epinephrine infusions started. o Diffuse blanching erythema noted. n No mucosal edema or wheezing. Case Description o Procedure cancelled. n Transported to medical ICU. n Weaned off vasopressors & extubated in 3 hours. n Serum tryptase 125 mcg/L (reference range 0.4 – 10.9). o Skin testing to bupivacaine: n No cutaneous, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular or respiratory symptoms. n No evidence of IgE-mediated hypersensitivity to bupivacaine. Discussion o Initial working diagnosis was a high or total spinal. o Tachycardia, skin changes and markedly elevated tryptase most consistent with anaphylactic reaction. -

Autonomic Hyperreflexia Associated with Recurrent Cardiac Arrest

Spinal Cord (1997) 35, 256 ± 257 1997 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/97 $12.00 Autonomic hyperre¯exia associated with recurrent cardiac arrest: Case Report SC Colachis, III1 and DM Clinchot2 1Associate Professor and 2Assistant Professor, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation1, Director, SCI Rehabilitation, The Ohio State University, College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio, USA Autonomic hyperre¯exia is a condition which may occur in individuals with spinal cord injuries above the splanchnic sympathetic out¯ow. Noxious stimuli can produce profound alterations in sympathetic pilomotor, sudomotor, and vasomotor activity, as well as disturbances in cardiac rhythm. A case of autonomic hyperre¯exia in a patient with C6 tetraplegia with recurrent ventricular ®brillation and cardiac arrest illustrates the profound eects of massive paroxysmal sympathetic activity associated with this condition. Keywords: autonomic hyperre¯exia; spinal cord injury; ventricular ®brillation Introduction Autonomic hyperre¯exia is a condition of paroxysmal by excessive sweating and ¯ushing. Past episodes of re¯ex sympathetic activity which occurs in response to autonomic hyperre¯exia were generally attributed to noxious stimuli in patients with spinal cord injuries re¯ex voiding, position changes and the presence of above the major splanchnic sympathetic out¯ow.1±3 pressure sores. The heightened sympathetic activity during an episode The attendant had completed the patient's morning of autonomic hyperre¯exia accounts for several of the bowel program, hygiene and dressing activities, and clinical features commonly observed including sudo- started to exit the apartment when he heard gasping. motor and pilomotor phenomenon,1,4 ± 6 vasomotor He returned to ®nd him pulseless, apneic, and sequelae,1 ± 4,7 and alterations in cardiac inotropic and cyanotic. -

Pediatric Shock

REVIEW Pediatric shock Usha Sethuraman† & Pediatric shock accounts for significant mortality and morbidity worldwide, but remains Nirmala Bhaya incompletely understood in many ways, even today. Despite varied etiologies, the end result †Author for correspondence of pediatric shock is a state of energy failure and inadequate supply to meet the metabolic Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Division of demands of the body. Although the mortality rate of septic shock is decreasing, the severity Emergency Medicine, is on the rise. Changing epidemiology due to effective eradication programs has brought in Carman and Ann Adams new microorganisms. In the past, adult criteria had been used for the diagnosis and Department of Pediatrics, 3901 Beaubien Boulevard, management of septic shock in pediatrics. These have been modified in recent times to suit Detroit, MI 48201, USA the pediatric and neonatal population. In this article we review the pathophysiology, Tel.: +1 313 745 5260 epidemiology and recent guidelines in the management of pediatric shock. Fax: +1 313 993 7166 [email protected] Shock is an acute syndrome in which the circu- to generate ATP. It is postulated that in the face of latory system is unable to provide adequate oxy- prolonged systemic inflammatory insult, overpro- gen and nutrients to meet the metabolic duction of cytokines, nitric oxide and other medi- demands of vital organs [1]. Due to the inade- ators, and in the face of hypoxia and tissue quate ATP production to support function, the hypoperfusion, the body responds by turning off cell reverts to anaerobic metabolism, causing the most energy-consuming biophysiological acute energy failure [2]. -

What Is the Autonomic Nervous System?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.74.suppl_3.iii31 on 21 August 2003. Downloaded from AUTONOMIC DISEASES: CLINICAL FEATURES AND LABORATORY EVALUATION *iii31 Christopher J Mathias J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74(Suppl III):iii31–iii41 he autonomic nervous system has a craniosacral parasympathetic and a thoracolumbar sym- pathetic pathway (fig 1) and supplies every organ in the body. It influences localised organ Tfunction and also integrated processes that control vital functions such as arterial blood pres- sure and body temperature. There are specific neurotransmitters in each system that influence ganglionic and post-ganglionic function (fig 2). The symptoms and signs of autonomic disease cover a wide spectrum (table 1) that vary depending upon the aetiology (tables 2 and 3). In some they are localised (table 4). Autonomic dis- ease can result in underactivity or overactivity. Sympathetic adrenergic failure causes orthostatic (postural) hypotension and in the male ejaculatory failure, while sympathetic cholinergic failure results in anhidrosis; parasympathetic failure causes dilated pupils, a fixed heart rate, a sluggish urinary bladder, an atonic large bowel and, in the male, erectile failure. With autonomic hyperac- tivity, the reverse occurs. In some disorders, particularly in neurally mediated syncope, there may be a combination of effects, with bradycardia caused by parasympathetic activity and hypotension resulting from withdrawal of sympathetic activity. The history is of particular importance in the consideration and recognition of autonomic disease, and in separating dysfunction that may result from non-autonomic disorders. CLINICAL FEATURES c copyright. General aspects Autonomic disease may present at any age group; at birth in familial dysautonomia (Riley-Day syndrome), in teenage years in vasovagal syncope, and between the ages of 30–50 years in familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP). -

REVIEW Autonomic Assessment of Animals with Spinal Cord

Spinal Cord (2009) 47, 2–35 & 2009 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/09 $32.00 www.nature.com/sc REVIEW Autonomic assessment of animals with spinal cord injury: tools, techniques and translation JA Inskip1,2,4, LM Ramer1,2,4, MS Ramer1,2 and AV Krassioukov1,3 1International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 2Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada and 3Department of Medicine, Division of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Study design: Literature review. Objectives: To present a comprehensive overview of autonomic assessment in experimental spinal cord injury (SCI). Methods: A systematic literature review was conducted using PubMed to extract studies that incorporated functional motor, sensory or autonomic assessment after experimental SCI. Results: While the total number of studies assessing functional outcomes of experimental SCI increased dramatically over the past 27 years, studies with motor outcomes dramatically outnumber those with autonomic outcomes. Within the areas of autonomic dysfunction (cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, lower urinary tract, sexual function and thermoregulation), not all aspects have been characterized to the same extent. Studies focusing on bladder and cardiovascular function greatly outnumber those on sexual function, gastrointestinal function and thermoregulation. This review addresses the disparity between well-established motor-sensory testing presently used in experimental animals and the lack of standardized autonomic testing following experimental SCI. Throughout the review, we provide information on the correlation between existing experimental and clinically used autonomic tests. Finally, the review contains a comprehensive set of tables and illustrations to guide the reader through the complexity of autonomic assessment and dysfunctions observed following SCI. -

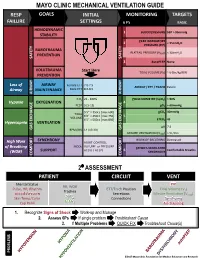

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Cardiovascular Complications During the Acute Phase of Spinal Cord Injury

Cardiovascular Complications during the Acute Phase of Spinal Cord Injury Mirkowski M Faltynek P Benton B McIntyre A Krassioukov A Teasell RW www.scireproject.com Version 7.0 Key Points Pseudoephedrine may be an effective adjuvant for the treatment of neurogenic shock during the acute phase post SCI; however, pseudoephedrine may require up to one month for effectiveness and may result in higher complication rates for older patients. The use of functional electrical stimulation in combination with tilt tables may be effective for the management of orthostatic hypotension during the acute and subacute phase post SCI. Tilt table verticalization may be effective for lowering heart rate in patients post SCI. Midodrine hydrochloride may be effective for the management of orthostatic hypotension during the acute phase post SCI. Methylprednisolone appear to not be effective for the management of heart rate variability post SCI. Hemodynamic support during the acute phase post SCI has been associated with improved neurological outcomes but no cause and effect relationship has been established. Oral albuterol appears to be effective for the management of bradycardia during the acute phase post SCI. Cardiac pacemaker implantation appears to be effective for the management of refractory bradycardia during the acute phase post SCI. Table of Contents 1.0 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Methods ........................................................................................................................................ -

Electrical Stimulation-Evoked Contractions Blunt Orthostatic Hypotension in Sub-Acute Spinal Cord-Injured Individuals: Two Clinical Case Studies

Spinal Cord (2015) 53, 375–379 & 2015 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/15 www.nature.com/sc ORIGINAL ARTICLE Electrical stimulation-evoked contractions blunt orthostatic hypotension in sub-acute spinal cord-injured individuals: two clinical case studies NA Hamzaid1, LT Tean1, GM Davis1,2, A Suhaimi3 and N Hasnan3 Study design: Prospective study of two cases. Objectives: To describe the effects of electrical stimulation (ES) therapy in the 4-week management of two sub-acute spinal cord- injured (SCI) individuals (C7 American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) B and T9 AIS (B)). Setting: University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Methods: A diagnostic tilt-table test was conducted to confirm the presence of orthostatic hypotension (OH) based on the current clinical definitions. Following initial assessment, subjects underwent 4 weeks of ES therapy 4 times weekly for 1 h per day. Post-tests tilt table challenge, both with and without ES on their rectus abdominis, quadriceps, hamstrings and gastrocnemius muscles, was conducted at the end of the study (week 5). Subjects’ blood pressures (BP) and heart rates (HR) were recorded every minute during pre- test and post-tests. Orthostatic symptoms, as well as the maximum tolerance time that the subjects could withstand head up tilt at 60°, were recorded. Results: Subject A improved his orthostatic symptoms, but did not recover from clinically defined OH based on the 20-min duration requirement. With concurrent ES therapy, 60° head up tilt BP was 89/62 mm Hg compared with baseline BP of 115/71 mm Hg. Subject B fully recovered from OH demonstrated by BP of 105/71 mm Hg during the 60° head up tilt compared with baseline BP of 124/77 mm Hg.