Neurogenic Shock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suplento1 Volumen 71 En

S1 Volumen 71 Mayo 2015 Revista Española de Vol. 71 Supl. 1 • Mayo 2015 Vol. Clínica e Investigación Órgano de expresión de la Sociedad Española de SEINAP Investigación en Nutrición y Alimentación en Pediatría Sumario XXX CONGRESO DE LA SOCIEDAD espaÑOLA DE CUIDADOS INTENSIVOS PEDIÁTRICOS Toledo, 7-9 de mayo de 2015 MESA REDONDA: ¿HACIA DÓNDE VAMOS EN LA MESA REDONDA: EL PACIENTE AGUDO MONITORIZACIÓN? CRONIFICADO EN UCIP 1 Monitorización mediante pulsioximetría: ¿sólo saturación 47 Nutrición en el paciente crítico de larga estancia en UCIP. de oxígeno? P. García Soler Z. Martínez de Compañón Martínez de Marigorta 3 Avances en la monitorización de la sedoanalgesia. S. Mencía 53 Traqueostomía, ¿cuándo realizarla? M.A. García Teresa Bartolomé y Grupo de Sedoanalgesia de la SECIP 60 Los cuidados de enfermería, ¿un reto? J.M. García Piñero 8 Avances en neuromonitorización. B. Cabeza Martín CHARLA-COLOQUIO SESIÓN DE PUESTA AL DÍA: ¿ES BENEFICIOSA LA 64 La formación en la preparación de las UCIPs FLUIDOTERAPIA PARA MI PACIENTE? españolas frente al riesgo de epidemias infecciosas. 13 Sobrecarga de líquidos y morbimortalidad asociada. J.C. de Carlos Vicente M.T. Alonso 68 Lecciones aprendidas durante la crisis del Ébola: 20 Estrategias de fluidoterapia racional en Cuidados experiencia del intensivista de adultos. J.C. Figueira Intensivos Pediátricos. P. de la Oliva Senovilla Iglesias 72 El niño con enfermedad por virus Ébola: un nuevo reto MESA REDONDA: INDICADORES DE CALIDAD para el intensivista pediátrico. E. Álvarez Rojas DE LA SECIP 23 Evolución de la cultura de seguridad en UCIP. MESA REDONDA: UCIP ABIERTAS 24 HORAS, La comunicación efectiva. -

Pediatric Shock

REVIEW Pediatric shock Usha Sethuraman† & Pediatric shock accounts for significant mortality and morbidity worldwide, but remains Nirmala Bhaya incompletely understood in many ways, even today. Despite varied etiologies, the end result †Author for correspondence of pediatric shock is a state of energy failure and inadequate supply to meet the metabolic Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Division of demands of the body. Although the mortality rate of septic shock is decreasing, the severity Emergency Medicine, is on the rise. Changing epidemiology due to effective eradication programs has brought in Carman and Ann Adams new microorganisms. In the past, adult criteria had been used for the diagnosis and Department of Pediatrics, 3901 Beaubien Boulevard, management of septic shock in pediatrics. These have been modified in recent times to suit Detroit, MI 48201, USA the pediatric and neonatal population. In this article we review the pathophysiology, Tel.: +1 313 745 5260 epidemiology and recent guidelines in the management of pediatric shock. Fax: +1 313 993 7166 [email protected] Shock is an acute syndrome in which the circu- to generate ATP. It is postulated that in the face of latory system is unable to provide adequate oxy- prolonged systemic inflammatory insult, overpro- gen and nutrients to meet the metabolic duction of cytokines, nitric oxide and other medi- demands of vital organs [1]. Due to the inade- ators, and in the face of hypoxia and tissue quate ATP production to support function, the hypoperfusion, the body responds by turning off cell reverts to anaerobic metabolism, causing the most energy-consuming biophysiological acute energy failure [2]. -

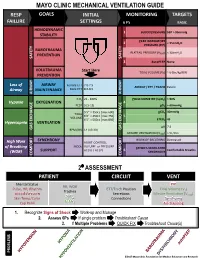

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Approach to Shock.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Approach to Shock.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Approach to Shock Developed by Dr. Dustin Jacobson and Dr Suzanne Beno for PedsCases.com. December 20, 2016 My name is Dustin Jacobson, a 3rd year pediatrics resident from the University of Toronto. This podcast was supervised by Dr. Suzanne Beno, a staff physician in the division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at the University of Toronto. Today, we’ll discuss an approach to shock in children. First, we’ll define shock and understand it’s pathophysiology. Next, we’ll examine the subclassifications of shock. Last, we’ll review some basic and more advanced treatment for shock But first, let’s start with a case. Jonny is a 6-year-old male who presents with lethargy that is preceded by 2 days of a diarrheal illness. He has not urinated over the previous 24 hours. On assessment, he is tachycardic and hypotensive. He is febrile at 40 degrees Celsius, and is moaning on assessment, but spontaneously breathing. We’ll revisit this case including evaluation and management near the end of this podcast. The term “shock” is essentially a ‘catch-all’ phrase that refers to a state of inadequate oxygen or nutrient delivery for tissue metabolic demand. This broad definition incorporates many causes that eventually lead to this end-stage state. Basic oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and content of oxygen in the blood. -

Hypothesis Spinal Shock and `Brain Death': Somatic Pathophysiological

Spinal Cord (1999) 37, 313 ± 324 ã 1999 International Medical Society of Paraplegia All rights reserved 1362 ± 4393/99 $12.00 http://www.stockton-press.co.uk/sc Hypothesis Spinal shock and `brain death': Somatic pathophysiological equivalence and implications for the integrative-unity rationale DA Shewmon*,1 1Pediatric Neurology, UCLA Medical School, Los Angeles, California, USA The somatic pathophysiology of high spinal cord injury (SCI) not only is of interest in itself but also sheds light on one of the several rationales proposed for equating `brain death' (BD) with death, namely that the brain confers integrative unity upon the body, which would otherwise constitute a mere conglomeration of cells and tissues. Insofar as the neuropathology of BD includes infarction down to the foramen magnum, the somatic pathophysiology of BD should resemble that of cervico-medullary junction transection plus vagotomy. The endocrinologic aspects can be made comparable either by focusing on BD patients without diabetes insipidus or by supposing the victim of high SCI to have pre-existing therapeutically compensated diabetes insipidus. The respective literatures on intensive care for BD organ donors and high SCI corroborate that the two conditions are somatically virtually identical. If SCI victims are alive at the level of the `organism as a whole', then so must be BD patients (the only signi®cant dierence being consciousness). Comparison with SCI leads to the conclusion that if BD is to be equated with death, a more coherent reason must be adduced than that the body as a biological organism is dead. Keywords: brain death; spinal cord injury; spinal shock; integrative functions; somatic integrative unity; organism as a whole Introduction Spinal shock is a transient functional depression of the society; its legal de®nition is culturally relative, and structurally intact cord below a lesion, following acute most modern societies happen to have chosen to spinal cord injury (SCI). -

Polytrauma Shock • Trauma Related Costs in the U.S

POLYTRAUMA SHOCK • TRAUMA RELATED COSTS IN THE U.S. 400 BILLION $ • 3.8 MILLION DEATHS PER YEAR • THE LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH IN PERSONS AGED 1 TO 45 IN THE MOST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES • TRIMODAL DEATH DISTRIBUTION 1. SECONDS, MINS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO BRAIN, C. SPINE, LARGE VESSEL INJ. 2. 1-2 HOURS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO EPIDURAL HAEMATOMAS, BLEEDINGS GOLDEN HOUR 3. SEVERAL DAYS FOLLOWING INJURY DUE TO M.O.F., SEPSIS TRIMODAL DEATH DISTRIBUTION 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% HOURS 0 1 2 3 4 WEEKS 1 2 3 4 TRIMODAL BIMODAL? THE SECOND GROUP IS DECREASING DUE TO PROPER TREATMENT GOLDEN HOUR NOT ONLY SALVAGEABILITY BUT MANY LATE PROBLEMS (SIRS, MOF) ARE THE CONSEQUENCES OF THE PRIMARY HYPOXIA AND MEDIATOR RELEASE SILVER DAY BRONZE WEEK PLATINA 10 MIN DEFINITION OF POLYTRAUMA A. INJURY TO ONE OR MORE BODY REGIONS OR ORGANS OF WHICH ONE, OR THEIR COMBINATIONS IS LIFE THREATENING B. INJURY TO MORE BODY REGIONS FOLLOWING WHICH, DURING TREATMENT, WE HAVE TO MAKE COMPROMISES C. INJURY TO HOLLOW ORGANS + INJURY TO EXTREMITIES D. INJURY DEFINED BY A SCORING SYSTEM TRAUMA SCORE NUMBER OF BREATHS PER MIN 0-4 INTENSITY OF BREATHING 0-1 SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE 0-4 CAPILLARY REFILL 0-2 GLASGOW COMA SCALE 0-5 POSSIBILITY FOR SURVIVAL 16+ <2 99% 0% GLASGOW COMA SCALE EYE OPENING SPONTANEOUS 4 TO SPEECH 3 TO PAIN 2 NONE 1 BEST MOTOR RESPONSE OBEYS COMMANDS 6 LOCALIZES PAIN 5 NORMAL FLEXION 4 ABNORMAL FLEXION 3 EXTENSION 2 NONE 1 VERBAL RESPONSE ORIENTED 5 CONFUSED CONVERS. 4 WORDS 3 SOUNDS 2 NOTHING 1 ABBREVIATED INJURY SCALE (ISS) 1 MILD 2 MEDIUM 3 SEVERE 4 VERY -

Definition Shock Is a Life-Threatening Condition That Occurs When the Body

Shock Definition Shock is a life-threatening condition that occurs when the body is not getting enough blood flow. This can damage multiple organs. Shock requires immediate medical treatment and can get worse very rapidly. Considerations Major classes of shock include: • Cardiogenic shock (associated with heart problems) • Hypovolemic shock (caused by inadequate blood volume) • Anaphylactic shock (caused by allergic reaction) • Septic shock (associated with infections) • Neurogenic shock (caused by damage to the nervous system) Causes Shock can be caused by any condition that reduces blood flow, including: • Heart problems (such as heart attack or heart failure ) • Low blood volume (as with heavy bleeding or dehydration ) • Changes in blood vessels (as with infection or severe allergic reactions ) Shock is often associated with heavy external or internal bleeding from a serious injury. Spinal injuries can also cause shock. Toxic shock syndrome is an example of a type of shock from an infection. Symptoms A person in shock has extremely low blood pressure. Depending on the specific cause and type of shock, symptoms will include one or more of the following: • Anxiety or agitation • Confusion • Pale, cool, clammy skin • Bluish lips and fingernails • Dizziness , light-headedness, fainting or unconsciousness • Profuse sweating , moist skin • Rapid but weak pulse • Shallow breathing • Chest pain First Aid • Call 911 for immediate medical help. • Check the person's airways, breathing, and circulation. If necessary, begin rescue breathing and CPR. • Even if the person is able to breathe on his or her own, continue to check rate of breathing at least every 5 minutes until help arrives. • If the person is conscious and does NOT have an injury to the head, leg, neck, or spine, place the person in the shock position. -

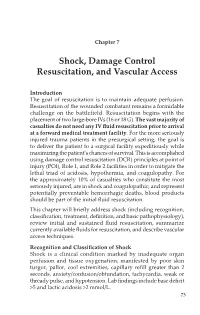

Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access

Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access Chapter 7 Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access Introduction The goal of resuscitation is to maintain adequate perfusion. Resuscitation of the wounded combatant remains a formidable challenge on the battlefield. Resuscitation begins with the placement of two large-bore IVs (16 or 18 G). The vast majority of casualties do not need any IV fluid resuscitation prior to arrival at a forward medical treatment facility. For the more seriously injured trauma patients in the presurgical setting, the goal is to deliver the patient to a surgical facility expeditiously while maximizing the patient’s chances of survival. This is accomplished using damage control resuscitation (DCR) principles at point of injury (POI), Role 1, and Role 2 facilities in order to mitigate the lethal triad of acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy. For the approximately 10% of casualties who constitute the most seriously injured, are in shock and coagulopathic, and represent potentially preventable hemorrhagic deaths, blood products should be part of the initial fluid resuscitation. This chapter will briefly address shock (including recognition, classification, treatment, definition, and basic pathophysiology), review initial and sustained fluid resuscitation, summarize currently available fluids for resuscitation, and describe vascular access techniques. Recognition and Classification of Shock Shock is a clinical condition marked by inadequate organ perfusion and tissue oxygenation, manifested by poor skin turgor, pallor, cool extremities, capillary refill greater than 2 seconds, anxiety/confusion/obtundation, tachycardia, weak or thready pulse, and hypotension. Lab findings include base deficit >5 and lactic acidosis >2 mmol/L. 73 Emergency War Surgery Hypovolemic shock: Diminished volume resulting in poor perfusion as a result of hemorrhage, diarrhea, dehydration, and burns. -

Lynn Fitzgerald Macksey

SHOCK STATES Lynn Fitzgerald Macksey RN, MSN, CRNA Define SHOCK : a state where tissue perfusion to vital organs is inadequate. Shock state In all shock states, the ultimate result is inadequate tissue perfusion, leading to a decreased delivery of oxygen and nutrients to cells…. and, therefore, cell energy. Clinical recognition of shock Symptoms dizziness, nausea, visual changes, thirst, dyspnea Signs cold clammy skin, pallor, confusion, agitation, diaphoresis, weak thready pulse, obvious injury Compensatory stages of shock Sympathetic nervous system Renin-angiotensin system Pituitary-antidiuretic hormone release Shunting from less critical areas to brain and heart Progressive decompensation Failure of compensatory mechanisms in Bowel CNS & autonomic Heart Kidneys Lungs Liver What will we see? Shock diagnosis Clinical examination Diagnostics: CXR CBC blood chemistry EKG ABG vital signs Monitoring organ perfusion in shock states Base deficit Blood lactate levels Normalization of these markers are the end point goals of resuscitation! Base Deficit Reflects severity of shock, the oxygen debt, changes in oxygen delivery, and the adequacy of fluid resuscitation. 2-5 mmol/L suggests mild shock 6-14 mmol/L indicates moderate shock > 14 mmol/L is a sign of severe shock Base Deficit The base deficit reflects the likelihood of multiple organ failure and survival. An admission base deficit in excess of 5-8 mmol/L correlates with increased mortality. Lactate Levels Blood lactate levels correlate with other signs of hypoperfusion. Normal lactate levels are 0.5-1.5 mmol/L >5 mmol/L indicate significant lactic acidosis. Lactate Levels Failure to clear lactate within 24 hours after circulatory shock is a predictor of increased mortality. -

A Systematic Review of the Evidence Supporting a Role for Vasopressor Support in Acute SCI

Spinal Cord (2010) 48, 356–362 & 2010 International Spinal Cord Society All rights reserved 1362-4393/10 $32.00 www.nature.com/sc REVIEW A systematic review of the evidence supporting a role for vasopressor support in acute SCI A Ploumis1,2, N Yadlapalli2, MG Fehlings3, BK Kwon4 and AR Vaccaro2 1Division of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Department of Surgery, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece; 2Department of Orthopaedics, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 3Division of Neurosurgery and Spinal Program, Department of Surgery, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and 4Department of Orthopaedics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Study design: A systematic review of clinical and preclinical literature. Objective: To critically evaluate the evidence supporting a role for vasopressor support in the management of acute spinal cord injury and to provide updated recommendations regarding the appropriate clinical application of this therapeutic modality. Background: Only few clinical studies exist examining the role of arterial pressure and vasopressors in the context of spinal cord trauma. Methods: Medical literature was searched from the earlier available date to July 2009 and 32 articles (animal and human literature) answering the following four questions were studied: what patient groups benefit from vasopressor support, which is the optimal hypertensive drug regimen, which is the optimal duration of the treatment and which is the optimal arterial blood pressure. Outcome measures used were the incidence of patients needing vasopressors, the increase of arterial blood pressure and neurologic improvement. Results: Patients with complete cervical cord injuries required vasopressors more frequently than either incomplete injuries or thoracic/lumbar cord injuries (Po0.001). -

System Specific Trauma

MODULE 3 System Specific Trauma | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 1 www.who.int/surgery OBJECTIVES FOR MODULE 3 To learn specific management strategies for trauma • Head • Spine and spinal cord • Chest • Abdomen • Female genitalia • Musculoskeletal system | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 2 www.who.int/surgery Head Injury | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 3 www.who.int/surgery HEAD INJURY • Altered level of consciousness is a hallmark of acute cerebral trauma • Never assume that substances (alcohol or drugs) are causes of drowsiness • Frequent clinical mistakes: – Incomplete ABC's, priority management – Incomplete primary, secondary surveys – Incomplete baseline neurologic examination – No reassessment of neurologic status | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 4 www.who.int/surgery HEAD INJURY Basal skull fractures – Periorbital ecchymosis (racoon eyes) – Mastoid ecchymosis (Battle's sign) – Cerebrospinal fluid leak from ears or nose Depressed skull fracture – Fragments of skull may penetrate dura, brain Cerebral concussion – Variable temporary altered consciousness | Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (EESC) programme 5 www.who.int/surgery HEAD INJURY Intracerebral hematoma – Caused by acute injury or delayed, progressive bleeding originating from contusion Clinical features of increased intracranial pressure: – Decreased level of consciousness – Bradycardia – Unequal or dilated pupils – Seizures – Focal neurologic deficit | Emergency and Essential -

Trauma: Spinal Cord Injury

Trauma: Spinal Cord Injury a, a,b Matthew J. Eckert, MD *, Matthew J. Martin, MD KEYWORDS Spine Spine trauma Spinal cord injury Spinal cord syndromes Spinal shock Spine immobilization KEY POINTS Hypotension following trauma should be considered secondary to hemorrhage until proven otherwise, even in patients with early suspicion of spinal injury. Neurogenic shock and spinal shock are separate, important entities that must be understood. Hypoxia and hypotension should be aggressively corrected because they lead to second- ary spinal cord injury, analogous to traumatic brain injury. Critical care support of multiple organ systems is frequently required early after injury. Early spinal decompression may lead to improved neurologic outcomes in select spinal cord injuries, and prompt consultation with spine surgeons is recommended. Computed tomography (CT) is the gold-standard screening study for evaluation of the spine after trauma and has significantly greater sensitivity and specificity compared with plain radiographs. High-quality CT imaging without evidence of cervical spine injury may be adequate for removal of the cervical immobilization collar in obtunded patients. INTRODUCTION Traumatic spine and spinal cord injury (SCI) occurred in roughly 17,000 US citizens in 2016, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 280,000 injured persons.1 Although the injury has historically been a disease of younger adult men, a progressive increase in SCI incidence among the elderly has been reported over the last few de- cades.2 Upwards of 70% of SCI patients suffer multiple injuries concomitant with spi- nal cord trauma, contributing to the high rates of associated complications during the acute and long-term phases of care.3 SCI is associated with significant reductions in life expectancy across the spectrum of injury and age at time of insult.1 Patients who survive the initial injury face significant risks of medical complications throughout the rest of their lives.