Shock, Damage Control Resuscitation, and Vascular Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiating Between Anxiety, Syncope & Anaphylaxis

Differentiating between anxiety, syncope & anaphylaxis Dr. Réka Gustafson Medical Health Officer Vancouver Coastal Health Introduction Anaphylaxis is a rare but much feared side-effect of vaccination. Most vaccine providers will never see a case of true anaphylaxis due to vaccination, but need to be prepared to diagnose and respond to this medical emergency. Since anaphylaxis is so rare, most of us rely on guidelines to assist us in assessment and response. Due to the highly variable presentation, and absence of clinical trials, guidelines are by necessity often vague and very conservative. Guidelines are no substitute for good clinical judgment. Anaphylaxis Guidelines • “Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening IgE mediated allergic reaction” – How many people die or have died from anaphylaxis after immunization? Can we predict who is likely to die from anaphylaxis? • “Anaphylaxis is one of the rarer events reported in the post-marketing surveillance” – How rare? Will I or my colleagues ever see a case? • “Changes develop over several minutes” – What is “several”? 1, 2, 10, 20 minutes? • “Even when there are mild symptoms initially, there is a potential for progression to a severe and even irreversible outcome” – Do I park my clinical judgment at the door? What do I look for in my clinical assessment? • “Fatalities during anaphylaxis usually result from delayed administration of epinephrine and from severe cardiac and respiratory complications. “ – What is delayed? How much time do I have? What is anaphylaxis? •an acute, potentially -

Hypovolemic Shock and Resuscitation Piper Lynn Wall Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1997 Hypovolemic shock and resuscitation Piper Lynn Wall Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, Physiology Commons, Surgery Commons, and the Veterinary Physiology Commons Recommended Citation Wall, Piper Lynn, "Hypovolemic shock and resuscitation " (1997). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 11754. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/11754 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi-om the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. -

Fluid Resuscitation Therapy for Hemorrhagic Shock

CLINICAL CARE Fluid Resuscitation Therapy for Hemorrhagic Shock Joseph R. Spaniol vides a review of the 4 types of shock, the 4 classes of Amanda R. Knight, BA hemorrhagic shock, and the latest research on resuscita- tive fluid. The 4 types of shock are categorized into dis- Jessica L. Zebley, MS, RN tributive, obstructive, cardiogenic, and hemorrhagic Dawn Anderson, MS, RN shock. Hemorrhagic shock has been categorized into 4 Janet D. Pierce, DSN, ARNP, CCRN classes, and based on these classes, appropriate treatment can be planned. Crystalloids, colloids, dopamine, and blood products are all considered resuscitative fluid treat- ment options. Each individual case requires various resus- ■ ABSTRACT citative actions with different fluids. Healthcare Hemorrhagic shock is a severe life-threatening emergency professionals who are knowledgeable of the information affecting all organ systems of the body by depriving tissue in this review would be better prepared for patients who of sufficient oxygen and nutrients by decreasing cardiac are admitted with hemorrhagic shock, thus providing output. This article is a short review of the different types optimal care. of shock, followed by information specifically referring to hemorrhagic shock. The American College of Surgeons ■ DISTRIBUTIVE SHOCK categorized shock into 4 classes: (1) distributive; (2) Distributive shock is composed of 3 separate categories obstructive; (3) cardiogenic; and (4) hemorrhagic. based on their clinical outcome. Distributive shock can be Similarly, the classes of hemorrhagic shock are grouped categorized into (1) septic; (2) anaphylactic; and (3) neu- by signs and symptoms, amount of blood loss, and the rogenic shock. type of fluid replacement. This updated review is helpful to trauma nurses in understanding the various clinical Septic shock aspects of shock and the current recommendations for In accordance with the American College of Chest fluid resuscitation therapy following hemorrhagic shock. -

Hypovolemic Shock

Ask the Expert Emergency Medicine / Critical Care Peer Reviewed Hypovolemic Shock Garret E. Pachtinger, VMD, DACVECC Veterinary Specialty & Emergency Center Levittown, Pennsylvania You have asked… What is hypovolemic shock, and how should I manage it? Retroperitoneal effusion in a dog The expert says… hock, a syndrome in which clinical deterioration can occur quickly, requires careful analy- All forms of shock share sis and rapid treatment. Broad definitions for shock include inadequate cellular energy pro- a common concern: Sduction or the inability of the body to supply cells and tissues with oxygen and nutrients and remove waste products. Shock may result from a variety of underlying conditions and can be inadequate perfusion. classified into the broad categories of septic, hemorrhagic, obstructive, and hypovolemic shock.1-3 Regardless of the underlying cause, all forms of shock share a common concern: inadequate per- fusion.1,2 Perfusion (ie, flow to or through a given structure or tissue bed) is imperative for nutri- ent and oxygen delivery, as well as removal of cellular waste and byproducts of metabolism. Lack of adequate perfusion can result in cell death, morbidity, and, ultimately, mortality. Hypovolemic shock is one of the most common categories of shock seen in clinical veterinary medicine.4 In hypovolemic shock, perfusion is impaired as a result of an ineffective circulating blood volume. During initial circulating volume loss, there are a number of mechanisms to com- pensate for decreases in perfusion, including increased levels of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate, result- ing in a rightward shift in the oxyhemoglobin dissociation curve and a decreased blood viscosity. -

Fluid Resuscitation in Trauma Patients: What Should We Know?

REVIEW CURRENT OPINION Fluid resuscitation in trauma patients: what should we know? Silvia Coppola, Sara Froio, and Davide Chiumello Purpose of review Fluid resuscitation in trauma patients could reduce organ failure, until blood components are available and hemorrhage is controlled. However, the ideal fluid resuscitation strategy in trauma patients remains a debated topic. Different types of trauma can require different types of fluids and different volume of infusion. Recent findings There are few randomized controlled trials investigating the efficacy of fluids in trauma patients. There is no evidence that any type of fluids can improve short-term and long-term outcome in these patients. The main clinical evidence emphasizes that a restrictive fluid resuscitation before surgery improves outcome in patients with penetrating trauma. Fluid management of blunt trauma patients, in particular with coexisting brain injury, remains unclear. Summary In order to focus on the state of the art about this topic, we review the current literature and guidelines. Recent studies have underlined that the correct fluid resuscitation strategy can depend on the type of trauma condition: penetrating, blunt, brain injury or a combination of them. Of course, further studies are needed to investigate the impact of a specific fluid strategy on different type and severity of trauma. Keywords blunt trauma, colloids, crystalloids, fluid resuscitation, penetrating trauma INTRODUCTION In the literature, there is little evidence that one type of fluid compared with another can improve Traumatic death is the main cause of life years lost & worldwide [1]. Hemorrhage is responsible for almost survival or can be more effective [4 ,6]. Few rando- 50% of deaths in the first 24 h after trauma [2,3]. -

Approach to Shock.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Approach to Shock.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Approach to Shock Developed by Dr. Dustin Jacobson and Dr Suzanne Beno for PedsCases.com. December 20, 2016 My name is Dustin Jacobson, a 3rd year pediatrics resident from the University of Toronto. This podcast was supervised by Dr. Suzanne Beno, a staff physician in the division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine at the University of Toronto. Today, we’ll discuss an approach to shock in children. First, we’ll define shock and understand it’s pathophysiology. Next, we’ll examine the subclassifications of shock. Last, we’ll review some basic and more advanced treatment for shock But first, let’s start with a case. Jonny is a 6-year-old male who presents with lethargy that is preceded by 2 days of a diarrheal illness. He has not urinated over the previous 24 hours. On assessment, he is tachycardic and hypotensive. He is febrile at 40 degrees Celsius, and is moaning on assessment, but spontaneously breathing. We’ll revisit this case including evaluation and management near the end of this podcast. The term “shock” is essentially a ‘catch-all’ phrase that refers to a state of inadequate oxygen or nutrient delivery for tissue metabolic demand. This broad definition incorporates many causes that eventually lead to this end-stage state. Basic oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and content of oxygen in the blood. -

Towards Non-Invasive Monitoring of Hypovolemia in Intensive Care Patients Alexander Roederer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (CIS) Department of Computer & Information Science 4-13-2015 Towards Non-Invasive Monitoring of Hypovolemia in Intensive Care Patients Alexander Roederer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] James Weimer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Joseph Dimartino University of Pennsylvania Health System, [email protected] Jacob Gutsche University of Pennsylvania Health System, [email protected] Insup Lee University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.upenn.edu/cis_papers Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, and the Computer Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Alexander Roederer, James Weimer, Joseph Dimartino, Jacob Gutsche, and Insup Lee, "Towards Non-Invasive Monitoring of Hypovolemia in Intensive Care Patients", 6th Workshop on Medical Cyber-Physical Systems (MedicalCPS 2015) . April 2015. 6th Workshop on Medical Cyber-Physical Systems (MedicalCPS 2015) http://workshop.medcps.org/ in conjunction with CPS Week 2015 http://www.cpsweek.org/2015/ Seattle, WA, April 13, 2015 An extended version of this paper is available at http://repository.upenn.edu/cis_papers/787/ This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. http://repository.upenn.edu/cis_papers/781 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Towards Non-Invasive Monitoring of Hypovolemia in Intensive Care Patients Abstract Hypovolemia caused by internal hemorrhage is a major cause of death in critical care patients. However, hypovolemia is difficult to diagnose in a timely fashion, as obvious symptoms do not manifest until patients are already nearing a critical state of shock. Novel non-invasive methods for detecting hypovolemia in the literature utilize the photoplethysmogram (PPG) waveform generated by the pulse-oximeter attached to a finger or ear. -

To Standardize Blood Pressure Goals in Bleeding Trauma Patients Undergoing Active Resuscitation

Division of Acute Care Surgery Clinical Practice Policies, Guidelines, and Algorithms: Controlled Resuscitation in Trauma Patients Clinical Practice Guideline Original Date: 06/2017 Purpose: To standardize blood pressure goals in bleeding trauma patients undergoing active resuscitation. Recommendations: Patient population Recommendation Adult blunt trauma patient without traumatic Resuscitate to a SBP >70 mmHg until hemorrhage brain injury is controlled Adult penetrating trauma patient without Resuscitate to a MAP > 50 mmHg or SBP >70 traumatic brain injury mmHg until hemorrhage controlled (GRADE Level of Quality – moderate; USPSTF strength of recommendation – B [intervention is recommended]) *Note: there is increasing interest in and use of resuscitative balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA). When used correctly, REBOA dramatically decreases blood pressure distal to the site of hemorrhage and, as such, is complimentary to controlled resuscitation, not contradictory. Summary of Public Health Impact: In 2013, injury was the most common cause of death among people ages 1-44 years, accounting for 59% of all deaths in this age range. There were over 192,900 deaths from injury, approximately one every 3 minutes.1 Since trauma is a disease of the young, injury accounts for the most life-years lost than any other disease – 30% of all life years lost in the U.S. compared to cancer 16% and heart disease 12%.2 Truncal hemorrhage accounts for 20-40% of trauma deaths occurring after hospital admission and continues to be a leading cause of potentially survivable deaths.3,4 This is despite a significant amount of time and healthcare resources attempting to address this problem, including: implementation of trauma systems5, utilization of in-house trauma surgeons6, and development of hemostatic resuscitation,7 to name a few. -

Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting

9/3/2020 Recognizing and Treating Shock in the Prehospital Setting 1 9/3/2020 Special Thanks to Our Sponsor 2 9/3/2020 Your Presenters Dr. Raymond L. Fowler, Dr. Melanie J. Lippmann, MD, FACEP, FAEMS MD FACEP James M. Atkins MD Distinguished Professor Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine of Emergency Medical Services, Brown University Chief of the Division of EMS Alpert Medical School Department of Emergency Medicine Attending Physician University of Texas Rhode Island Hospital and The Miriam Hospital Southwestern Medical Center Providence, RI Dallas, TX 3 9/3/2020 Scenario SHOCK INDEX?? Pulse ÷ Systolic 4 9/3/2020 What is Shock? Shock is a progressive state of cellular hypoperfusion in which insufficient oxygen is available to meet tissue demands It is key to understand that when shock occurs, the body is in distress. The shock response is mounted by the body to attempt to maintain systolic blood pressure and brain perfusion during times of physiologic distress. This shock response can accompany a broad spectrum of clinical conditions that stress the body, ranging from heart attacks, to major infections, to allergic reactions. 5 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Shock may be caused when oxygen intake, absorption, or delivery fails, or when the cells are unable to take up and use the delivered oxygen to generate sufficient energy to carry out cellular functions. 6 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Hypovolemic Shock Distributive Shock Inadequate circulating fluid leads A precipitous increase in vascular to a diminished cardiac output, capacity as blood vessels dilate and which results in an inadequate the capillaries leak fluid, translates into delivery of oxygen to the too little peripheral vascular resistance tissues and cells and a decrease in preload, which in turn reduces cardiac output 7 9/3/2020 Causes of Shock Cardiogenic Shock Obstructive Shock The heart is unable to circulate Obstruction to the forward flow of sufficient blood to meet the blood exists in the great vessels metabolic needs of the body. -

RDCR – PRINCIPLES NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen REMOTE DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION

NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen RDCR – PRINCIPLES NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen REMOTE DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION ¡ Is the implementation of damage control principles in austere environments NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen DAMAGE CONTROL RESUSCITATION: NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen TEMPORARY HEMORRHAGE CONTROL NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen PERMISSIVE HYPOTENSION NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen HEMOSTATIC RESUSCITATION NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen DAMAGE CONTROL SURGERY (DAMAGE CONTROL RADIOLOGICAL INTERVENTION) NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen RESTORING ORGAN PERFUSION IN ICU NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen PERMISSIVE HYPOTENSION: “PRESERVING COAGULATION, REDUCING BLEEDING WHILE SACRIFISING PERFUSION” NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen PERMISSIVE HYPOTENSION Goals of Fluid Resuscitation Therapy • Improved state of consciousness (if no TBI) • Palpable radial pulse corresponds roughly to systolic blood pressure of 80 mm Hg?? • Avoid over-resuscitation of shock from torso wounds. • Too much fluid volume may make internal hemorrhage worse by “Popping the Clot.” NORSOCOM NORSOCOM Marinejegerkommandoen ¡ Not a treatment ¡ Necessary evil?? ¡ Evidence???? Bicknell WH, Wall MJ, Pepe PE, Martin RR, Ginger VF, Allen MK, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1105-9 Turner J, Nicholl J, Webber L, Cox H, Dixon S, Yates D. A randomised controlled trial of prehospital intravenous fluid replacement therapy in serious trauma. Health Technology Assessment 2000;4:1-57. Dutton RP, Mackenzie CF, Scalae TM. Hypotensive resuscitation during active haemorrhage: impact on hospital mortality. J Trauma 2002;52:1141-6. SAFE Study Investigators; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group; Australian Red Cross Blood Service; George Institute for International Health, Myburgh J, Cooper DJ, et al. Saline or albumin for fluid resuscitation in patients with traumatic brain injury. -

Permissive Hypotension: Changing Tide of Trauma Fluid Resuscitation

Permissive Hypotension Jeff Myers, DO, EdM, NREMT‐P, FAAEM June 2009 [email protected] Permissive Hypotension: Changing Tide of Trauma Fluid Resuscitation Jeff Myers, D.O., Ed.M., NREMT-P, FAAEM Clinical Assistant Professor Emergency Medicine SUNY-Buffalo, Buffalo, NY [email protected] http://ems-ed.photoemsdoc.com/ 716.898.3525 Objectives: Describe the history of fluids in trauma resuscitation Understand the pathophysiology of hemorrhagic shock Understand the rationale for limiting IV fluids during trauma resuscitation History of Fluid Resuscitation: Traditional resuscitation guidelines ¾ 2 large bore IVs ¾ Infusion of 2 liters normal saline or lactated ringers Hypotension in Trauma occurs in ________ of both blunt and penetrating trauma victims. The civilian rate is approximately ________ and the recent military rate is ________ ¾ Approximately _____ of victims of trauma who are hypotensive die early, either _____________ or ___________________ and are _____________________________. This rate has been stable since the Crimean War and is not affected by trauma system development ¾ Approximately _____ of victims of trauma who are hypotensive are hypotensive from _______________________________ causes. These causes include: o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ o _______________________________ ¾ Approximately _____ of victims of trauma who are hypotensive are hypotensive secondary to _______________________ and are the focus of the discussion. Cannon, Fraser, Cowell. Preventative treatment of wound shock. JAMA 1918 noted poor outcomes with IV Fluid resuscitation Page 1 of 8 Permissive Hypotension Jeff Myers, DO, EdM, NREMT‐P, FAAEM June 2009 [email protected] ¾ “Inaccessible or uncontrolled source of blood loss should not be treated with intravenous fluids until the time of surgical control” Beecher. -

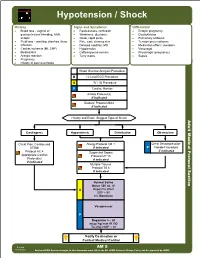

AM 05 Hypotension Shock Protocol Final 2017 Editable.Pdf

Hypotension / Shock History Signs and Symptoms Differential • Blood loss - vaginal or • Restlessness, confusion • Ectopic pregnancy gastrointestinal bleeding, AAA, • Weakness, dizziness • Dysrhythmias ectopic • Weak, rapid pulse • Pulmonary embolus • Fluid loss - vomiting, diarrhea, fever • Pale, cool, clammy skin • Tension pneumothorax • Infection • Delayed capillary refill • Medication effect / overdose • Cardiac ischemia (MI, CHF) • Hypotension • Vasovagal • Medications • Coffee-ground emesis • Physiologic (pregnancy) • Allergic reaction • Tarry stools • Sepsis • Pregnancy • History of poor oral intake Blood Glucose Analysis Procedure B 12 Lead ECG Procedure A IV / IO Procedure P Cardiac Monitor Airway Protocol(s) if indicated Diabetic Protocol AM 2 if indicated History and Exam Suggest Type of Shock Adult Medical Protocol Section Protocol Adult Medical Cardiogenic Hypovolemic Distributive Obstructive Chest Pain: Cardiac and Allergy Protocol AM 1 Chest Decompression- STEMI if indicated P Needle Procedure if indicated Protocol AC 4 Suspected Sepsis Appropriate Cardiac Protocol UP 15 Protocol(s) if indicated if indicated Multiple Trauma Protocol TB 6 if indicated A P Notify Destination or Contact Medical Control Revised AM 5 02/18/2019 Any local EMS System changes to this document must follow the NC OEMS Protocol Change Policy and be approved by OEMS Hypotension / Shock Adult Medical Protocol Section Protocol Adult Medical Pearls • Recommended Exam: Mental Status, Skin, Heart, Lungs, Abdomen, Back, Extremities, Neuro • Hypotension can be defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 90. This is not always reliable and should be interpreted in context and patients typical BP if known. Shock may be present with a normal blood pressure initially. • Shock often is present with normal vital signs and may develop insidiously.