Trauma Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3

ISSN: 2643-4474 Raval et al. Neurosurg Cases Rev 2020, 3:046 DOI: 10.23937/2643-4474/1710046 Volume 3 | Issue 2 Neurosurgery - Cases and Reviews Open Access CASE REPORT Case Report: A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3 1 Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Gujarat, India Check for updates 2Medical Officer, CHC Dolasa, Gujarat, India 3GAIMS-GK General Hospital, Gujarat, India *Corresponding author: Dr. Himanshu Raval, Resident, Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Elisbridge, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380006, India, Tel: 942-955-3329 Abstract Introduction Background: Head injury is common component of any Road traffic accident (RTA) is the most common road traffic accident injury. Injury involving only frontal sinus cause of cranio-facial injury and involvement of frontal is uncommon and unique as its management algorithm is bone fractures are rare and constitute 5-9% of only fa- changing over time with development of radiological modal- ities as well as endoscopic intervention. Frontal sinus inju- cial trauma. The degree of association has been report- ries may range from isolated anterior table fractures causing ed to be 95% with fractures of the anterior table or wall a simple aesthetic deformity to complex fractures involving of the frontal sinuses, 60% with the orbital rims, and the frontal recess, orbits, skull base, and intracranial con- 60% with complex injuries of the naso-orbital-ethmoid tents. Only anterior table injury of frontal sinus is rare in pen- region, 33% with other orbital wall fractures and 27% etrating head injury without underlying brain injury with his- tory of unconsciousness and questionable convulsion which with Le Fort level fractures. -

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

Traumatic Intracranial Aneurysms Due to Penetrating Brain Injury. a Case Report and Suggested Management Guidelines Breck Aaron Jones MD; Alex Patrick Michael MD

Traumatic Intracranial Aneurysms Due to Penetrating Brain Injury. A Case Report and Suggested Management Guidelines Breck Aaron Jones MD; Alex Patrick Michael MD Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Methods Learning Objectives Introduction Angiogram Traumatic intracranial aneurysms A Pubmed search of the literature Identification of traumatic intracranial pertaining to traumatic aneurysms. (TICA) are rare in occurrence and pseudoaneurysms and penetrating Classification of traumatic intracranial equally rare in the literature. Less brain trauma. The literature was aneurysms. than 1% of intracranial aneurysms reviewed for case reports and Treatment and management of are caused by blunt trauma, while management recommendations. traumatic intracranial aneurysms. even fewer are caused by penetrating trauma. Penetrating Results References Traumatic intracranial aneurysm 1.Aarabi B. Management of traumatic aneurysms caused by trauma creates a unique type of high-velocity missile head wounds. Neurosurg Clin N Am. formation is the most commonly aneurysm that does not incorporate Oct 1995;6(4):775-797. described vascular injury after 2.Rao GP, Rao NS, Reddy PK. Technique of removal of an all three vessel wall layers. Because penetrating brain injury. impacted sharp object in a penetrating head injury using the of their rarity, the natural history and Histologically, traumatic aneurysms lever principle. Br J Neurosurg. Dec 1998;12(6):569-571. 3.Vascular complications of penetrating brain injury. J can be described as true management of TICAs are not well Trauma. Aug 2001;51(2 Suppl):S26-28. Angiogram showing traumatic intracranial (incorporating intima, media, defined in the literature. Here we 4.Crompton MR. The pathogenesis of cerebral aneurysms. aneurysm following a gunshot wound to adventitia), false (incorporating one or Brain. -

Blunt and Blast Head Trauma: Different Entities

International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, 115–118 (2009) Blunt and Blast Head Trauma: Different Entities Michael E. Hoffer,1 Chadwick Donaldson,1 Kim R. Gottshall1, Carey Balaban,2 and Ben J. Balough1 1 Spatial Orientation Center, Department of Otolaryngology, Naval Medical Center San Diego, San Diego, California, and 2 Department of Otolaryngology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA Abstract: Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) caused by blast-related and blunt head trauma is frequently encountered in clinical practice. Understanding the nuances between these two distinct types of injury leads to a more focused approach by clinicians to develop better treat- ment strategies for patients. In this study, we evaluated two separate cohorts of mTBI patients to ascertain whether any difference exists in vestibular-ocular reflex (VOR) testing (n ϭ 55 en- rolled patients: 34 blunt, 21 blast) and vestibular-spinal reflex (VSR) testing (n ϭ 72 enrolled patients: 33 blunt, 39 blast). The VOR group displayed a preponderance of patients with blunt mTBI, demonstrating normal to high-frequency phase lag on rotational chair testing, whereas patients experiencing mTBI from blast-related causes revealed a trend toward low-frequency phase lag on evaluation. The VSR cohort showed that patients with posttraumatic migraine- associated dizziness tended to test higher on posturography. However, an indepth look at the total patient population in this second cohort reveals that a higher percentage of blast-exposed patients exhibited a significantly increased latency on motor control testing as compared to pa- tients with blunt head injury ( p Ͻ .02). These experiments identify a distinct difference be- tween blunt-injury and blast-injury mTBI patients and provide evidence that treatment strategies should be individualized on the basis of each mechanism of injury. -

Chest Trauma in Children

Chest Trauma In Children Donovan Dwyer MBBCh, DCH, DipPEC, FACEM Emergency Physician St George and Sydney Children’s Hospitals Director of Trauma, Sydney Children’s Hospital Disclaimer • This cannot be comprehensive • Trying to give trauma clinicians a perspective on paediatric differences • Trying to give emergency paediatric clinicians a perspective on trauma challenges • The format will focus on take home salient points related to ED dx and management • I may gloss over slides with more detail and references to keep to time • As most chest mortality is in the 12-15 yr age group, where paediatric evidence is low, I have looked to adult evidence OVERVIEW • Size of the problem • Common injuries – pitfalls and tips • Less common injuries – where recognition and time is critical • Blunt vs penetrating • The Chest in Traumatic Cardiac Arrest Size of the problem • Overall paediatric trauma in Australasia is low volume • Parents take injured children to nearest hospital for primary care • Prehospital services will divert to nearest facility with critically injured children Chest Injury • RV of Victorian State Trauma Registry in 2001–2007 = 204 cases • < 1/week • Blunt trauma - 96% • motor vehicle collisions (75%) • pedestrian (26%) • vehicle occupants (33%) Size of the problem • Common injuries – combined 50% of the time • lung contusion (66%) • haemo/pneumothorax (32%) • rib fracture (23%). • Associated multiple organ injury 90% • head (62%) • abdominal (50%) • Management conservative/supportive > 80% • Surgical • 11 cases (7%) treated surgically • 30% invasive • 18 cases(11%) had insertion of intercostal catheters (ICC). • Epidemiology of major paediatric chest trauma, Sumudu P Samarasekera ET AL, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health (2009) International • 85 % Blunt –MVA – 45% • Ped vs car – 20% • Falls – 10% • NAI – 7% • Penetrating 15% • Mortality • Cooper A. -

Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study

SPINE Volume 31, Number 4, pp 451–458 ©2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study Allan D. Levi, MD, PhD,* R. John Hurlbert, MD, PhD,† Paul Anderson, MD,‡ Michael Fehlings, MD, PhD,§ Raj Rampersaud, MD,§ Eric M. Massicotte, MD,§ John C. France, MD, Jean Charles Le Huec, MD, PhD,¶ Rune Hedlund, MD,** and Paul Arnold, MD†† Study Design. A retrospective study was undertaken their neurologic injury. The most common reason for the that evaluated the medical records and imaging studies of missed injury was insufficient imaging studies (58.3%), a subset of patients with spinal injury from large level I while only 33.3% were a result of misread radiographs or trauma centers. 8.3% poor quality radiographs. The incidence of missed Objective. To characterize patients with spinal injuries injuries resulting in neurologic injury in patients with who had neurologic deterioration due to unrecognized spine fractures or strains was 0.21%, and the incidence as instability. a percentage of all trauma patients evaluated was 0.025%. Summary of Background Data. Controversy exists re- Conclusions. This multicenter study establishes that garding the most appropriate imaging studies required to missed spinal injuries resulting in a neurologic deficit “clear” the spine in patients suspected of having a spinal continue to occur in major trauma centers despite the column injury. Although most bony and/or ligamentous presence of experienced personnel and sophisticated im- spine injuries are detected early, an occasional patient aging techniques. Older age, high impact accidents, and has an occult injury, which is not detected, and a poten- patients with insufficient imaging are at highest risk. -

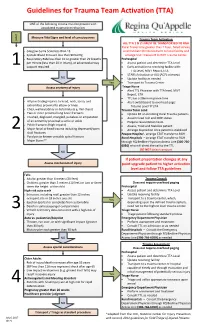

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

Isolated Severe Blunt Traumatic Brain Injury: Effect of Obesity on Outcomes

CLINICAL ARTICLE J Neurosurg 134:1667–1674, 2021 Isolated severe blunt traumatic brain injury: effect of obesity on outcomes Jennifer T. Cone, MD, MHS,1 Elizabeth R. Benjamin, MD, PhD,2 Daniel B. Alfson, MD,2 and Demetrios Demetriades, MD, PhD2 1Department of Surgery, Section of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, University of Chicago, Illinois; and 2Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma, Emergency Surgery, and Surgical Critical Care, LAC+USC Medical Center, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California OBJECTIVE Obesity has been widely reported to confer significant morbidity and mortality in both medical and surgical patients. However, contemporary data indicate that obesity may confer protection after both critical illness and certain types of major surgery. The authors hypothesized that this “obesity paradox” may apply to patients with isolated severe blunt traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). METHODS The Trauma Quality Improvement Program (TQIP) database was queried for patients with isolated severe blunt TBI (head Abbreviated Injury Scale [AIS] score 3–5, all other body areas AIS < 3). Patient data were divided based on WHO classification levels for BMI: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2), obesity class 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m2), obesity class 2 (35.0–39.9 kg/m2), and obesity class 3 (≥ 40.0 kg/ m2). The role of BMI in patient outcomes was assessed using regression models. RESULTS In total, 103,280 patients were identified with isolated severe blunt TBI. Data were excluded for patients aged < 20 or > 89 years or with BMI < 10 or > 55 kg/m2 and for patients who were transferred from another treatment center or who showed no signs of life upon presentation, leaving data from 38,446 patients for analysis. -

Fat Embolism Syndrome – a Qualitative Review of Its Incidence, Presentation, Pathogenesis and Management

2-RA_OA1 3/24/21 6:00 PM Page 1 Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal 2021 Vol 15 No 1 Timon C, et al doi: https://doi.org/10.5704/MOJ.2103.001 REVIEW ARTICLE Fat Embolism Syndrome – A Qualitative Review of its Incidence, Presentation, Pathogenesis and Management Timon C, MCh, Keady C, MSc, Murphy CG, FRCS Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Galway University Hospitals, Galway, Ireland This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited Date of submission: 12th November 2020 Date of acceptance: 05th March 2021 ABSTRACT DEFINITION AND INTRODUCTION Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES) is a poorly defined clinical Fat embolism 1 occurs when fat enters the circulation, this fat phenomenon which has been attributed to fat emboli entering can embolise and may or may not produce clinical the circulation. It is common, and its clinical presentation manifestations. may be either subtle or dramatic and life threatening. This is a review of the history, causes, pathophysiology, FES is a poorly defined clinical phenomenon which has been presentation, diagnosis and management of FES. FES mostly attributed to fat emboli entering the circulation. It classically occurs secondary to orthopaedic trauma; it is less frequently presents with respiratory, neurological and dermatological associated with other traumatic and atraumatic conditions. features. It typically occurs after long-bone fractures and There is no single test for diagnosing FES. Diagnosis of FES total hip arthroplasty, less frequently it is caused by burns is often missed due to its subclinical presentation and/or and soft tissue injuries 2. -

Prehospital Spine Immobilization for Penetrating Trauma—Review and Recommendations from the Prehospital Trauma Life Support Executive Committee

REVIEW ARTICLE Prehospital Spine Immobilization for Penetrating Trauma—Review and Recommendations From the Prehospital Trauma Life Support Executive Committee Lance E. Stuke, MD, MPH, Peter T. Pons, MD, Jeffrey S. Guy, MD, MSc, MMHC, Will P. Chapleau, RN, EMT-P, Frank K. Butler, MD, Capt MC USN (Ret), and Norman E. McSwain, MD pine immobilization in trauma patients suspected of hav- In the case of penetrating injuries, delays in transport Sing a spinal injury has been a cornerstone of prehospital prolong the time before patients receive the prompt surgical treatment for decades. Current practices are based on the care needed to arrest hemorrhage. Even with experienced belief that a patient with an injured spinal column can prehospital providers, spine immobilization is time consum- deteriorate neurologically without immobilization. Most ing. The time required for experienced emergency medical treatment protocols do not differentiate between blunt and technicians to properly immobilize a cervical spine has been penetrating mechanisms of injury. Current Emergency Med- reported to be 5.64 minutes (Ϯ1.49 minutes).6 This scene ical Service (EMS) protocols for spinal immobilization of delay can be catastrophic for a patient with penetrating penetrating trauma are based on historic practices rather than trauma requiring urgent surgical intervention for airway com- scientific merits. Although blunt spinal column injuries will promise or hemorrhage. Studies have demonstrated that cervical collars increase occasionally produce unstable vertebral -

Deaths from Abdominal Trauma: Analysis of 1888 Forensic Autopsies

DOI: 10.1590/0100-69912017006006 Original Article Deaths from abdominal trauma: analysis of 1888 forensic autopsies Óbitos por trauma abdominal: análise de 1888 autopsias médico-legais POLYANNA HELENA COELHO BORDONI1; DANIELA MAGALHÃES MOREIRA DOS SANTOS2; JAÍSA SANTANA TEIXEIRA2; LEONARDO SANTOS BORDONI2-4. ABSTRACT Objective: to evaluate the epidemiological profile of deaths due to abdominal trauma at the Forensic Medicine Institute of Belo Horizonte, MG - Brazil. Methods: we conducted a retrospective study of the reports of deaths due to abdominal trauma autopsied from 2006 to 2011. Results: we analyzed 1.888 necropsy reports related to abdominal trauma. Penetrating trauma was more common than blunt one and gun- shot wounds were more prevalent than stab wounds. Most of the individuals were male, brown-skinned, single and occupationally active. The median age was 34 years. The abdominal organs most injured in the penetrating trauma were the liver and the intestines, and in blunt trauma, the liver and the spleen. Homicide was the most prevalent circumstance of death, followed by traffic accidents, and almost half of the cases were referred to the Forensic Medicine Institute by a health unit. The blood alcohol test was positive in a third of the necropsies where it was performed. Cocaine and marijuana were the most commonly found substances in toxicology studies. Conclusion: in this sam- ple. there was a predominance of penetrating abdominal trauma in young, brown and single men, the liver being the most injured organ. Keywords: Autopsy. Forensic Medicine. Homicide. Abdominal Injuries. INTRODUCTION In addition, the accuracy of abdominal phy- sical examination is low and the level of consciousness eaths from external causes represent the second produced by hemorrhages or by the association of ab- Dleading cause of mortality in Brazil and the main dominal trauma (AT) with traumatic brain injury and/or cause when considering individuals under the age of effects of central nervous system of previously consu- 351. -

Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education

Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education April 2017 Authors Acknowledgments Jessica Dym Bartlett, MSW, PhD We are grateful to our reviewers, Elizabeth Jordan, Senior Research Scientist Jason Lang, Robyn Lipkowitz, David Murphey, Child Welfare/Early Childhood Development Cindy Oser, and Kathryn Tout. We also thank Child Trends the Alliance for Early Success for its support of this work. Sheila Smith, PhD Director, Early Childhood National Center for Children in Poverty Mailman School of Public Health Columbia University Elizabeth Bringewatt, MSW, PhD Research Scientist Child Welfare Child Trends Copyright Child Trends 2017 | Publication # 2017-19 Helping Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma: Policies and Strategies for Early Care and Education Table of Contents Executive Summary .............................................................1 Introduction ..........................................................................3 What is Early Childhood Trauma? ................................. 4 The Impacts of Early Childhood Trauma ......................5 Meeting the Needs of Young Children Who Have Experienced Trauma ...........................................................7 Putting It Together: Trauma-Informed Care for Young Children .....................................................................8 Promising Strategies for Meeting the Needs of Young Children Exposed to Trauma ..............................9 Recommendations ...........................................................