Western Trauma Association Critical Decisions in Trauma: Penetrating Chest Trauma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3

ISSN: 2643-4474 Raval et al. Neurosurg Cases Rev 2020, 3:046 DOI: 10.23937/2643-4474/1710046 Volume 3 | Issue 2 Neurosurgery - Cases and Reviews Open Access CASE REPORT Case Report: A Rare Case of Penetrating Trauma of Frontal Sinus with Anterior Table Fracture Himanshu Raval1*, Mona Bhatt2 and Nihar Gaur3 1 Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Gujarat, India Check for updates 2Medical Officer, CHC Dolasa, Gujarat, India 3GAIMS-GK General Hospital, Gujarat, India *Corresponding author: Dr. Himanshu Raval, Resident, Department of Neurosurgery, NHL Municipal Medical College, SVP Hospital Campus, Elisbridge, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, 380006, India, Tel: 942-955-3329 Abstract Introduction Background: Head injury is common component of any Road traffic accident (RTA) is the most common road traffic accident injury. Injury involving only frontal sinus cause of cranio-facial injury and involvement of frontal is uncommon and unique as its management algorithm is bone fractures are rare and constitute 5-9% of only fa- changing over time with development of radiological modal- ities as well as endoscopic intervention. Frontal sinus inju- cial trauma. The degree of association has been report- ries may range from isolated anterior table fractures causing ed to be 95% with fractures of the anterior table or wall a simple aesthetic deformity to complex fractures involving of the frontal sinuses, 60% with the orbital rims, and the frontal recess, orbits, skull base, and intracranial con- 60% with complex injuries of the naso-orbital-ethmoid tents. Only anterior table injury of frontal sinus is rare in pen- region, 33% with other orbital wall fractures and 27% etrating head injury without underlying brain injury with his- tory of unconsciousness and questionable convulsion which with Le Fort level fractures. -

Traumatic Intracranial Aneurysms Due to Penetrating Brain Injury. a Case Report and Suggested Management Guidelines Breck Aaron Jones MD; Alex Patrick Michael MD

Traumatic Intracranial Aneurysms Due to Penetrating Brain Injury. A Case Report and Suggested Management Guidelines Breck Aaron Jones MD; Alex Patrick Michael MD Southern Illinois University School of Medicine Methods Learning Objectives Introduction Angiogram Traumatic intracranial aneurysms A Pubmed search of the literature Identification of traumatic intracranial pertaining to traumatic aneurysms. (TICA) are rare in occurrence and pseudoaneurysms and penetrating Classification of traumatic intracranial equally rare in the literature. Less brain trauma. The literature was aneurysms. than 1% of intracranial aneurysms reviewed for case reports and Treatment and management of are caused by blunt trauma, while management recommendations. traumatic intracranial aneurysms. even fewer are caused by penetrating trauma. Penetrating Results References Traumatic intracranial aneurysm 1.Aarabi B. Management of traumatic aneurysms caused by trauma creates a unique type of high-velocity missile head wounds. Neurosurg Clin N Am. formation is the most commonly aneurysm that does not incorporate Oct 1995;6(4):775-797. described vascular injury after 2.Rao GP, Rao NS, Reddy PK. Technique of removal of an all three vessel wall layers. Because penetrating brain injury. impacted sharp object in a penetrating head injury using the of their rarity, the natural history and Histologically, traumatic aneurysms lever principle. Br J Neurosurg. Dec 1998;12(6):569-571. 3.Vascular complications of penetrating brain injury. J can be described as true management of TICAs are not well Trauma. Aug 2001;51(2 Suppl):S26-28. Angiogram showing traumatic intracranial (incorporating intima, media, defined in the literature. Here we 4.Crompton MR. The pathogenesis of cerebral aneurysms. aneurysm following a gunshot wound to adventitia), false (incorporating one or Brain. -

STAB WOUNDS PENETRATING the LEFT ATRIUM by MILROY PAUL from the General Hospital, Colombo, Ceylon

Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thx.16.2.190 on 1 June 1961. Downloaded from Thorax (1961), 16, 190. STAB WOUNDS PENETRATING THE LEFT ATRIUM BY MILROY PAUL From the General Hospital, Colombo, Ceylon (RECEIVED FOR PUBLICATION NOVEMBER 15, 1960) A stab wound penetrating the left atrium followed by 4 pints of dextran throughout the night. (excluding the left auricle) would have to penetrate At 7 a.m. the next day he was still alive, breathing through other chambers of the heart or through quietly, with a pulse of 122 of good volume, blood the great arteries at their origin from the heart to pressure 100/70 mm. Hg, and warm extremities. Although there was still no blood in the bank, an reach the left atrium from the front of the chest. operation was decided on and begun at 8 a.m. Bv Such wounds would be fatal, the patient dying this time the pulse had again become small, although from profuse haemorrhage within a few minutes. the extremities were warm. The left chest was opened A stab wound through the back of the chest could through an intercostal incision in the eighth intercostal reach the left atrium in the narrow sulcus between space. The left pleural cavity contained fluid blood the root of the left lung in front and the oeso- and clots. In the outer surface of the lung under- phagus and descending thoracic aorta behind, but lying the stab wound of the chest wall there was a placing a wound at this site without at the same stab wound of the lung. -

Case Report Forearm Compartment Syndrome Following Thrombolytic Therapy for Massive Pulmonary Embolism: a Case Report and Review of Literature

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Case Reports in Orthopedics Volume 2011, Article ID 678525, 4 pages doi:10.1155/2011/678525 Case Report Forearm Compartment Syndrome following Thrombolytic Therapy for Massive Pulmonary Embolism: A Case Report and Review of Literature Ravi Badge and Mukesh Hemmady Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics Surgery, Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Trust, Wigan WN1 2NN, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Ravi Badge, [email protected] Received 2 November 2011; Accepted 6 December 2011 Academic Editor: M. K. Lyons Copyright © 2011 R. Badge and M. Hemmady. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Use of thrombolytic therapy in pulmonary embolism is restricted in cases of massive embolism. It achieves faster lysis of the thrombus than the conventional heparin therapy thus reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with PE. The compartment syndrome is a well-documented, potentially lethal complication of thrombolytic therapy and known to occur in the limbs involved for vascular lines or venepunctures. The compartment syndrome in a conscious and well-oriented patient is mainly diagnosed on clinical ground with its classical signs and symptoms like disproportionate pain, tense swollen limb and pain on passive stretch. However these findings may not be appropriately assessed in an unconscious patient and therefore the clinicians should have high index of suspicion in a patient with an acutely swollen tense limb. In such scenarios a prompt orthopaedic opinion should be considered. In this report, we present a case of acute compartment syndrome of the right forearm in a 78 years old male patient following repeated attempts to secure an arterial line for initiating the thrombolytic therapy for the management of massive pulmonary embolism. -

Orthopedic Trauma Postoperative Care and Rehab

Orthopedic Trauma Postoperative Care and Rehab Serge Charles Kaska, MD Name that Beach 100$ Still 100$ 75$ 50$ 1$ Omaha • June 6th 1941 • !st Infantry Division • 2000 KIA LIFE OR LIMB THREAT 1. Compartment Syndrome 2. Fat Emboli Syndrome 3. Pulmonary Embolism 4. Shock Compartment syndrome case A 16 year old male was retrieving a tire from his truck bed on the side of the highway in the pouring rain when a car careens off of the road and sandwiches the patients legs between the bumpers at freeway speed. Acute compartment syndrome Compartment syndrome DEFINED Definition: Elevated tissue pressure within a closed fascial space • Pathogenesis – Too much in-flow: results in edema or hemorrhage – Decreased outflow: results in venous obstruction caused by tight dressing and/or cast. • Reduces tissue perfusion • Results in cell death Compartment syndrome tissue survival • Muscle – 3-4 hours: reversible changes – 6 hours: variable damage – 8 hours: irreversible changes • Nerve – 2 hours: looses nerve conduction – 4 hours: neuropraxia – 8 hours: irreversible changes Physical exam 1. Pain 2. Pain 3. Pain Physical exam • Inspection – Swelling, skin is tight and shiny • Motion – Active motion will be refused or unable. Must see dorsiflexion • Palpation – Severe pain with palpation • Alarming pain with passive stretch Physical exam • Dorsiflexion Physical Exam • Palpation – Severe pain with palpation • Alarming pain with passive stretch Physical exam • Evaluations from nurses, therapists, and orthotech’s are CRITICAL • If you call a doctor and say that -

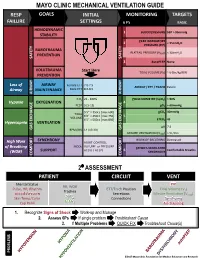

Mechanical Ventilation Guide

MAYO CLINIC MECHANICAL VENTILATION GUIDE RESP GOALS INITIAL MONITORING TARGETS FAILURE SETTINGS 6 P’s BASIC HEMODYNAMIC 1 BLOOD PRESSURE SBP > 90mmHg STABILITY PEAK INSPIRATORY 2 < 35cmH O PRESSURE (PIP) 2 BAROTRAUMA PLATEAU PRESSURE (P ) < 30cmH O PREVENTION PLAT 2 SAFETY SAFETY 3 AutoPEEP None VOLUTRAUMA Start Here TIDAL VOLUME (V ) ~ 6-8cc/kg IBW PREVENTION T Loss of AIRWAY Female ETT 7.0-7.5 AIRWAY / ETT / TRACH Patent Airway MAINTENANCE Male ETT 8.0-8.5 AIRWAY AIRWAY FiO2 21 - 100% PULSE OXIMETRY (SpO2) > 90% Hypoxia OXYGENATION 4 PEEP 5 [5-15] pO2 > 60mmHg 5’5” = 350cc [max 600] pCO2 40mmHg TIDAL 6’0” = 450cc [max 750] 5 VOLUME 6’5” = 500cc [max 850] ETCO2 45 Hypercapnia VENTILATION pH 7.4 GAS GAS EXCHANGE BPM (RR) 14 [10-30] GAS EXCHANGE MINUTE VENTILATION (VMIN) > 5L/min SYNCHRONY WORK OF BREATHING Decreased High Work ASSIST CONTROL MODE VOLUME or PRESSURE of Breathing PATIENT-VENTILATOR AC (V) / AC (P) 6 Comfortable Breaths (WOB) SUPPORT SYNCHRONY COMFORT COMFORT 2⁰ ASSESSMENT PATIENT CIRCUIT VENT Mental Status PIP RR, WOB Pulse, HR, Rhythm ETT/Trach Position Tidal Volume (V ) Trachea T Blood Pressure Secretions Minute Ventilation (V ) SpO MIN Skin Temp/Color 2 Connections Synchrony ETCO Cap Refill 2 Air-Trapping 1. Recognize Signs of Shock Work-up and Manage 2. Assess 6Ps If single problem Troubleshoot Cause 3. If Multiple Problems QUICK FIX Troubleshoot Cause(s) PROBLEMS ©2017 Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research CAUSES QUICK FIX MANAGEMENT Bleeding Hemostasis, Transfuse, Treat cause, Temperature control HYPOVOLEMIA Dehydration Fluid Resuscitation (End points = hypoxia, ↑StO2, ↓PVI) 3rd Spacing Treat cause, Beware of hypoxia (3rd spacing in lungs) Pneumothorax Needle D, Chest tube Abdominal Compartment Syndrome FLUID Treat Cause, Paralyze, Surgery (Open Abdomen) OBSTRUCTED BLOOD RETURN Air-Trapping (AutoPEEP) (if not hypoxic) Pop off vent & SEE SEPARATE CHART PEEP Reduce PEEP Cardiac Tamponade Pericardiocentesis, Drain. -

Acute Compartment Syndrome Complicating Deep Venous Thrombosis

SMGr up Case Report SM Journal of Acute Compartment Syndrome Case Reports Complicating Deep Venous Thrombosis Senthil Dhayalan1*, David Jardine1*, Tony Goh2 and Nicholas Lash3 1Senior registrar and General Physician, Dept of General Medicine, NZ 2Consultant Radiologist, Dept of Radiology, NZ 3Orthopaediac Surgeon, Dept of Orthopaedics, NZ A 40-yr old, heavily-built man initially presented to his general practitioner 2 days before Article Information admission with recent onset of pain and swelling in his left calf. A duplex ultrasound scan Received date: Nov 21, 2018 demonstrated a popliteal and lower leg deep vein thrombosis [DVT], extending 15 cm above the Accepted date: Nov 26, 2018 knee into the femoral vein. He was started appropriately on enoxaparin 130 mg bd. Despite the Published date: Nov 27, 2018 treatment, the pain got worse, particularly when standing, and he was admitted for symptom control. Five weeks earlier he had undergone anterior cruciate ligament repair of the left knee, *Corresponding author [without heparin prophylaxis] and made a satisfactory recovery (Figure 1). Jardine D, General Medicine On examination he was mildly distressed with a low-normal blood pressure [110/70 mmHg] Department, Christchurch hospital, and a persistent low-grade fever [temperature ranged from 37.0-37.8 oC]. The left leg was moderately Private Bag 4710, Christchurch 8140, diffusely swollen, slightly warm and darker in colour [figure]. The pain was localised to the posterior New Zealand, compartments and was exacerbated by dorsi-flexing the ankle and squeezing the gastrocnemius. Email: [email protected] There were no signs of joint effusion, thrombophlebitis, lymphadenopathy or cellulitis. -

Prehospital Spine Immobilization for Penetrating Trauma—Review and Recommendations from the Prehospital Trauma Life Support Executive Committee

REVIEW ARTICLE Prehospital Spine Immobilization for Penetrating Trauma—Review and Recommendations From the Prehospital Trauma Life Support Executive Committee Lance E. Stuke, MD, MPH, Peter T. Pons, MD, Jeffrey S. Guy, MD, MSc, MMHC, Will P. Chapleau, RN, EMT-P, Frank K. Butler, MD, Capt MC USN (Ret), and Norman E. McSwain, MD pine immobilization in trauma patients suspected of hav- In the case of penetrating injuries, delays in transport Sing a spinal injury has been a cornerstone of prehospital prolong the time before patients receive the prompt surgical treatment for decades. Current practices are based on the care needed to arrest hemorrhage. Even with experienced belief that a patient with an injured spinal column can prehospital providers, spine immobilization is time consum- deteriorate neurologically without immobilization. Most ing. The time required for experienced emergency medical treatment protocols do not differentiate between blunt and technicians to properly immobilize a cervical spine has been penetrating mechanisms of injury. Current Emergency Med- reported to be 5.64 minutes (Ϯ1.49 minutes).6 This scene ical Service (EMS) protocols for spinal immobilization of delay can be catastrophic for a patient with penetrating penetrating trauma are based on historic practices rather than trauma requiring urgent surgical intervention for airway com- scientific merits. Although blunt spinal column injuries will promise or hemorrhage. Studies have demonstrated that cervical collars increase occasionally produce unstable vertebral -

Deaths from Abdominal Trauma: Analysis of 1888 Forensic Autopsies

DOI: 10.1590/0100-69912017006006 Original Article Deaths from abdominal trauma: analysis of 1888 forensic autopsies Óbitos por trauma abdominal: análise de 1888 autopsias médico-legais POLYANNA HELENA COELHO BORDONI1; DANIELA MAGALHÃES MOREIRA DOS SANTOS2; JAÍSA SANTANA TEIXEIRA2; LEONARDO SANTOS BORDONI2-4. ABSTRACT Objective: to evaluate the epidemiological profile of deaths due to abdominal trauma at the Forensic Medicine Institute of Belo Horizonte, MG - Brazil. Methods: we conducted a retrospective study of the reports of deaths due to abdominal trauma autopsied from 2006 to 2011. Results: we analyzed 1.888 necropsy reports related to abdominal trauma. Penetrating trauma was more common than blunt one and gun- shot wounds were more prevalent than stab wounds. Most of the individuals were male, brown-skinned, single and occupationally active. The median age was 34 years. The abdominal organs most injured in the penetrating trauma were the liver and the intestines, and in blunt trauma, the liver and the spleen. Homicide was the most prevalent circumstance of death, followed by traffic accidents, and almost half of the cases were referred to the Forensic Medicine Institute by a health unit. The blood alcohol test was positive in a third of the necropsies where it was performed. Cocaine and marijuana were the most commonly found substances in toxicology studies. Conclusion: in this sam- ple. there was a predominance of penetrating abdominal trauma in young, brown and single men, the liver being the most injured organ. Keywords: Autopsy. Forensic Medicine. Homicide. Abdominal Injuries. INTRODUCTION In addition, the accuracy of abdominal phy- sical examination is low and the level of consciousness eaths from external causes represent the second produced by hemorrhages or by the association of ab- Dleading cause of mortality in Brazil and the main dominal trauma (AT) with traumatic brain injury and/or cause when considering individuals under the age of effects of central nervous system of previously consu- 351. -

Bilateral Atraumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Legs Leading to Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure Following Prolonged Kneeling in a Heroin Addict

PAJT 10.5005/jp-journals-10030-1075 CASE REPORTBilateral Atraumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Legs Leading to Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure Bilateral Atraumatic Compartment Syndrome of the Legs Leading to Rhabdomyolysis and Acute Renal Failure Following Prolonged Kneeling in a Heroin Addict. A Case Report and Review of Relevant Literature Saptarshi Biswas, Ramya S Rao, April Duckworth, Ravi Kothuru, Lucio Flores, Sunil Abrol ABSTRACT cerrado, que interfiere con la circulación de los componentes mioneurales del compartimento. Síndrome compartimental Introduction: Compartment syndrome is defined as a symptom bilateral de las piernas es una presentación raro que requiere complex caused by increased pressure of tissue fluid in a closed una intervención quirúrgica urgente. En un reporte reciente osseofascial compartment which interferes with circulation (Khan et al 2012), ha habido reportados solo 8 casos de to the myoneural components of the compartment. Bilateral síndrome compartimental bilateral. compartment syndrome of the legs is a rare presentation Se sabe que el abuso de heroína puede causar el síndrome requiring emergent surgical intervention. In a recent case report compartimental y rabdomiólisis traumática y atraumática. El (Khan et al 2012) there have been only eight reported cases hipotiroidismo también puede presentarse independiente con cited with bilateral compartment syndrome. rabdomiólisis. Heroin abuse is known to cause compartment syndrome, traumatic and atraumatic rhabdomyolysis. Hypothyroidism can Presentación del caso: Presentamos un caso de una mujer also independently present with rhabdomyolysis. de 22 años quien presentó con tumefacción bilateral de las piernas asociado con la perdida de la sensación, después Case presentation: We present a case of a 22 years old female de pasar dos días arrodillado contra una pared después de who presented with bilateral swelling of the legs with associated usar heroína intravenosa. -

Assessment, Management and Decision Making in the Treatment of Polytrauma Patients with Head Injuries

Compartment Syndrome Andrew H. Schmidt, M.D. Professor, Dept. of Orthopedic Surgery, Univ. of Minnesota Chief, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery Hennepin County Medical Center April 2016 Disclosure Information Andrew H. Schmidt, M.D. Conflicts of Commitment/ Effort Board of Directors: OTA Critical Issues Committee: AOA Editorial Board: J Knee Surgery, J Orthopaedic Trauma Medical Director, Director Clinical Research: Hennepin County Med Ctr. Disclosure of Financial Relationships Royalties: Thieme, Inc.; Smith & Nephew, Inc. Consultant: Medtronic, Inc.; DGIMed; Acumed; St. Jude Medical (spouse) Stock: Conventus Orthopaedics; Twin Star Medical; Twin Star ECS; Epien; International Spine & Orthopedic Institute, Epix Disclosure of Off-Label and/or investigative Uses I will not discuss off label use and/or investigational use in my presentation. Objectives • Review Pathophysiology of Acute Compartment Syndrome • Review Current Diagnosis and Treatment – Risk Factors – Clinical Findings – Discuss role and technique of compartment pressure monitoring. Pathophysiology of Compartment Syndrome Pressure Inflexible Fascia Injured Muscle Vascular Consequences of Elevated Intracompartment Pressure: A-V Gradient Theory Pa (High) Pv (Low) artery arteriole capillary venule vein Local Blood Pa - Pv Flow = R Matsen, 1980 Increased interstitial pressure Pa (High) Tissue ischemia artery arteriole capillary venule vein Lysis of cell walls Release of osmotically active cellular contents into interstitial fluid Increased interstitial pressure More cellular -

Updated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Guideline for Adults

Heads Up to Clinicians: Updated Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Guideline for Adults This Guideline is based on the 2008 Mild TBI Clinical Policy for adults, which revises the previous 2002 Clinical Policy. To help improve diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for patients with mild TBI, it is critical that you become familiar with this guideline. The guideline is especially important for clinicians working in hospital-based emergency care. Inclusion Criteria: This guideline is intended for patients with non-penetrating trauma to the head who present to the ED within 24 hours of injury, who have a Glascow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 14 or 15 on initial evaluation in the ED, and are ≥ 16 years old. Exclusion Criteria: This guideline is not intended for patients with penetrating trauma or multisystem trauma who have a GCS score of < 14 on initial evaluation in the ED and are < 16 years old. Please turn over. What You Need to Know: This guideline provides recommendations for determining which patients with a known or suspected mild TBI require a head CT and which may be safely discharged. Here are a few important points to note: There is no evidence to recommend the use of a head Discuss discharge instructions with patients and give MRI over a CT in acute evaluation. them a discharge instruction sheet to take home and share with their family and/or caregiver. Be sure to: A noncontrast head CT is indicated in head trauma patients with loss of consciousness or posttraumatic • Alert patients to look for postconcussive symptoms amnesia in presence of specific symptoms.