The Image of a Generation (Gender) Images of Heroin Addicts and Their Parents in the Netherlands, 1980-1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Milieubeweging, Speler Van Belang?

Milieubeweging, speler van belang? Een casusonderzoek naar de strategie van de milieubeweging in Nederland ten tijde van het kabinet-Den Uyl. Auteur: Steven Kastelijns Studentnummer: S4153685 Master: Politiek & Parlement Scriptiebegeleider: Adriejan van Veen Datum: 31-08-2018 Aantal woorden: 16.354 Inhoudsopgave blz.2 Voorwoord blz. 4 Afkortingenlijst blz. 5 Inleiding blz. 6 Tijdsafbakening blz. 8 Afbakening begrippen blz. 8 Status quaestionis blz. 12 - De relevantie van de Nederlandse milieubeweging blz. 12 - Het bestaande beeld van de milieubeweging blz. 12 - De indeling van wetenschappelijk onderzoek blz. 13 - De bijdrage van dit onderzoek aan de wetenschap blz. 17 Hoofdvraag blz. 18 Casus van het onderzoek blz. 20 Methode blz. 22 Hoofdstuk 1. De Nederlandse milieubeweging tot begin jaren 1970 blz. 25 - De Nederlandse milieubeweging tot de jaren zeventig blz. 25 - Ontstaan milieubeweging blz. 27 - De milieubeweging verandert blz. 29 - Deelconclusie deelvraag 1 blz. 31 Hoofdstuk 2. Het Nederlands milieubeleid tot begin jaren 1970 blz. 32 - De ontwikkeling van het milieubeleid blz. 32 - Natuurbeschermingsbeleid tot begin jaren zeventig blz. 32 - Opkomst beschermd milieubeleid blz. 33 - De opkomst van de lobbyisten blz. 35 - Het karakter van het Kabinet-Den Uyl blz. 36 - Deelconclusie deelvraag 2 blz. 38 - Besluitvorming rondom het Dollardkanaal blz. 39 - Deelconclusie deelvraag 3 blz. 40 Hoofdstuk 3. De lobby van de gematigde milieubeweging inzake het Dollardkanaal blz. 42 - De lobby van de milieubeweging blz. 42 - De conclusies van de RPC worden gepubliceerd blz. 46 - De bewindvoerders komen naar Groningen blz. 47 - De ministerraad beslist blz. 48 - Deelconclusie deelvraag 4 blz. 49 Conclusie blz. 50 - Discussie blz. 51 - Aanbevelingen vervolgonderzoek blz. -

CMYK 0/50/100/0And Guus Sluiter CMYK 0/70/100/0 RGB 150/160/25 RGB 215/215/0 RGB 255/150/0 RGB 255/105/10

On the kader kleurschema Waterfront huisstijlhandboek thonik © 2011 newsletter of the friends of the IISH 2015 no. 30 Interview with Archive Lectures on Funeral Marcel van der Linden Koos Vorrink Culture by Wim Cappers CMYK 50/25/100/0 CMYK 25/0/100/0 CMYK 0/50/100/0and Guus Sluiter CMYK 0/70/100/0 RGB 150/160/25 RGB 215/215/0 RGB 255/150/0 RGB 255/105/10 CMYK 0/100/100/0 CMYK 0/100/0/0 CMYK 0/50/0/0 CMYK 40/100/0/0 RGB 225/0/25 RGB 225/0/125 RGB 255/160/195 RGB 165/0/125 CMYK 70/70/0/0 CMYK 100/100/0/0 CMYK 100/0/50/0 CMYK 100/0/0/0 RGB 100/90/160 RGB 25/40/130 RGB 0/150/145 RGB 0/160/225 11 On the Waterfront 30 – 2015 Intro duction Cover photo: I will start this selection of important news from research project The Historical Dynamics of Industri- Passport Koos the past six months with updates about the col- alization in Northwestern Europe and China (1800-2010). Vorrink, 1947 lections. Rather than the usual paper archives, Spanning 5 years, the ERC project will be con- See page 5 the following project is likely to become increas- ducted under the aegis of Bas by a research team ingly commonplace. Andreas Admasie, Stefano comprising two PhD candidates, a post doc, and a Bellucci, and Marien van der Heijden travelled research assistant. At present the dynamics at the to the Bahir Dar Textile Factory in Ethiopia to iish are no cause for complaint at all. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/163231 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-27 and may be subject to change. HARE EXCELLENTIE! LR – Monique Leyenaar – Monique Leyenaar, hoogleraar Vergelijkende Politicologie aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, be- spreekt naar aanleiding van haar onlangs verschenen boek Hare Excellentie: 60 jaar vrouwelijke ministers in Nederland, enkele aspecten van 60 jaar vrouwelijk ministerschap. Namelijk de selectie en de betekenis van het vrouw-zijn. Zij belicht met name de ervaring van de VVD-ministers. Het ministerschap is een eervolle baan, gekenmerkt zij wisselen elkaar af.A Het duurt een kwart eeuw door veel macht en status. Het is een begeerde positie voordat twee vrouwelijke ministers in één kabinet waarvoor velen zich geroepen voelen, maar slechts worden benoemd. In 1982 hebben Neelie Smit- weinigen zijn uitverkoren: in de periode 1956-2016 Kroes en Eegje Schoo zitting in het eerste kabinet gaat het om 180 mannen en 33 vrouwen. van premier Ruud Lubbers. In die jaren staat vrou- De eerste vrouwelijke minister is Marga Klom- wenemancipatie hoog op de politieke agenda en pé. Zij speelt ten tijde van de formatie al een be- zowel de VVD-top als de beoogd premier gaan op langrijke rol in de KVP en is bevriend met partij- zoek naar vrouwelijke kandidaten voor het minister- leider Carl Romme. Hij wil dat het relatief nieuwe schap.B In de paarse kabinetten van premier Wim ministerie Maatschappelijk Werk voor zijn partij Kok (1994-2002) vinden we vier vrouwen en in het behouden blijft en dat de KVP de eerste vrouwelijke tweede, derde en vierde kabinet van minister-presi- minister gaat leveren. -

The Tinbergen & Hueting Approach in the Economics

THE TINBERGEN & H UETING APPROACH IN THE ECONOMICS OF NATIONAL ACCOUNTS AND ECOLOGICAL SURVIVAL 2 DRAFT The Tinbergen & Hueting Approach in the Economics of National Accounts and Ecological Survival Thomas Colignatus Samuel van Houten Genootschap 3 Lawful exceptions excluded, nothing of this publication may be copied or published by means of print, photocopy, microfilm, electronics or otherwise, unless a written permit has been given by the lawful owners of the copyright, and this also holds for whole or partial reworkings. Behoudens uitzondering door de wet gesteld mag zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de rechthebbende(n) op het auteursrecht niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm, electronica of anderszins, hetgeen ook van toepassing is op gehele of gedeeltelijke bewerking. April 17 2019 & March 6 2020, draft ISBN Published by Copyright © 2019 & 2020 Thomas H.A.M. Cool, and parts Roefie Hueting (Appendix 52), inheritance Salah el Serafy (Appendix 53), and parts from Hueting & De Boer (2019) http://thomascool.eu, cool at dataweb.nl Colignatus is the preferred name of Thomas Cool in science. I thank Roefie Hueting, Bart de Boer, Thea Sigmond and Henk van Tuinen for their comments over some years now. All errors remain mine. Cover © 2020 Thomas H.A.M. Cool. Painting by Hans van den Doel (1937-2012) showing Jan Tinbergen, Pieter Hennipman, Amartya Sen, Roefie Hueting, Van den Doel himself and Jos de Beus. This painting has been donated by his widow Keesjaa Blok to -

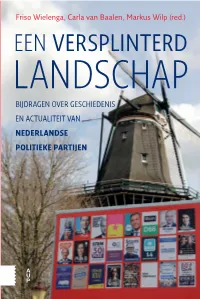

Een Versplinterd Landschap Belicht Deze Historische Lijn Voor Alle Politieke NEDERLANDSE Partijen Die in 2017 in De Tweede Kamer Zijn Gekozen

Markus Wilp (red.) Wilp Markus Wielenga, CarlaFriso vanBaalen, Friso Wielenga, Carla van Baalen, Markus Wilp (red.) Het Nederlandse politieke landschap werd van oudsher gedomineerd door drie stromingen: christendemocraten, liberalen en sociaaldemocraten. Lange tijd toonden verkiezingsuitslagen een hoge mate van continuïteit. Daar kwam aan het eind van de jaren zestig van de 20e eeuw verandering in. Vanaf 1994 zette deze ontwikkeling door en sindsdien laten verkiezingen EEN VERSPLINTERD steeds grote verschuivingen zien. Met de opkomst van populistische stromingen, vanaf 2002, is bovendien het politieke landschap ingrijpend veranderd. De snelle veranderingen in het partijenspectrum zorgen voor een over belichting van de verschillen tussen ‘toen’ en ‘nu’. Bij oppervlakkige beschouwing staat de instabiliteit van vandaag tegenover de gestolde LANDSCHAP onbeweeglijkheid van het verleden. Een dergelijk beeld is echter een ver simpeling, want ook in vroeger jaren konden de politieke spanningen BIJDRAGEN OVER GESCHIEDENIS hoog oplopen en kwamen kabinetten regelmatig voortijdig ten val. Er is EEN niet alleen sprake van discontinuïteit, maar ook wel degelijk van een doorgaande lijn. EN ACTUALITEIT VAN VERSPLINTERD VERSPLINTERD Een versplinterd landschap belicht deze historische lijn voor alle politieke NEDERLANDSE partijen die in 2017 in de Tweede Kamer zijn gekozen. De oudste daarvan bestaat al bijna honderd jaar (SGP), de jongste partijen (DENK en FvD) zijn POLITIEKE PARTIJEN nagelnieuw. Vrijwel alle bijdragen zijn geschreven door vertegenwoordigers van de wetenschappelijke bureaus van de partijen, waardoor een unieke invalshoek is ontstaan: wetenschappelijke distantie gecombineerd met een beschouwing van ‘binnenuit’. Prof. dr. Friso Wielenga is hoogleraardirecteur van het Zentrum für NiederlandeStudien aan de Westfälische Wilhelms Universität in Münster. LANDSCHAP Prof. -

Final Reports Template

MSP-LSI – Maritime Spatial Planning and Land-Sea Interactions Targeted Analysis Version: 20/02/2020 Final Case Study Report: Netherlands This targeted analysis activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Sue Kidd, Stephen Jay, Hannah Jones, Leonnie Robinson, Dave Shaw – University of Liverpool (UK) Marta Pascual, Diletta Zonta, Ecorys (Belgium) Katrina Abhold, Ina Kruger , Katriona McGlade, Ecologic Institute (Germany) Dania Abdhul Malak, Antonio Sanchez, University of Malaga (Spain) Advisory Group Project Steering Group: Holger Janssen, Ministry of Energy, Infrastructure and Digitalization Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany (Lead Stakeholder); Lenca Humerca-Solar,Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, Directorate Spatial Planning, Construction and Housing, Slovenia, Katarzyna Krzwda & Agata Zablocka, Ministry of Maritime Economy and Inland Navigation, Department for Maritime Economy, Poland, Sandra Momcilovic, Ministry of Construction and Physical Planning, Croatia, Katharina Ermenger and Gregor Forschbach, Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure, Division G 31 European Spatial Development Policy and Territorial Cohesion, Germany, Lodewijk Abspoel, Ministry for Infrastructure and Water Management, Netherlands. ESPON EGTC Michaela Gensheimer, Senior Project Expert, Johannes Kiersch, Financial Expert Version 20/02/2020 Information on ESPON and its projects can be found on www.espon.eu. -

Emotie in De Politiek

r - - Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis ^ 2003 Emotie in de politiek / Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 2003 Emotie in de politiek Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis Emotie in de politiek Redactie: C.C. van Baaien W. Breedveld J.W.L. Brouwer P.G.T.W. van Griensven J.J.M. Ramakers W.R Secker Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag Foto omslag: Roel Rozenburg Vormgeving omslag en binnenwerk: Wim Zaat, Moerkapelle Zetwerk: Wil van Dam, Utrecht Druk en afwerking: A-D Druk BV, Zeist © 2003, Centrum voor Parlementaire Geschiedenis, Nijmegen Alle rechthebbenden van illustraties hebben wij getracht te achterhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen aanspraak te maken op een vergoeding, dan verzoeken wij u contact op te nemen met de uitgever (www.sdu.nl). Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the publisher. isbn 90 12 09 9 6 7 6 issn 15 6 6 -5 0 5 4 Inhoud Ten geleide 7 Artikelen 11 Retnieg Aerts, Emotie in de politiek. Over politieke stijlen in Nederland sinds 1848 12 Rady B. Andeweg en Jacques Thomassen, Tekenen aan de wand? Kamerleden, kiezers en commentatoren over de kwaliteit van de parlementaire democratie in Nederland 26 Carla van Baaien, Cry if I want to? Politici in tranen 36 Ulla Jansz, Hartstocht en opgewondenheid. Kamerdebatten over mensenrechten in de koloniën rond 1850 47 Marij Leenders, ‘Gesol met de rechten van vervolgde mensen.’ Emoties in het asieldebat 1938-1999 57 Carla Hoetink, Als de hamer valt. -

Vloedgolf of Stroomversnelling? Protest

Vloedgolf of stroomversnelling? Protest tegen de afsluiting van de Oosterschelde tussen 1958 (aannemen van de Deltawet) en 1970 (de oprichting van de Aktiegroep Oosterschelde Open) Student: Suzanne de Lijser Studentnummer: s3046419 Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Studie: Master Actuele Geschiedenis Begeleider: dr. W.P. van Meurs Datum: 15 april 2016 Inhoud Inleiding 3 Hoofdstuk 1: Breed protest tegen een gesloten Oosterschelde, 1970-1974 7 1.1 De Aktiegroep Oosterschelde Open: het stereotype beeld van protesterende 7 jongeren, ludieke acties en veel media-aandacht in de jaren zeventig 1.2 De tijdgeest van de jaren zeventig: verlangen naar hervorming en aandacht 9 voor het milieu Hoofdstuk 2: De politieke omslag in het Oosterschelde-beleid 13 2.1 De Oosterschelde in het kabinet-Den Uyl 13 2.2 Het Kamerdebat: ‘de ouwe eerlijke dam’ of een ‘geavanceerd experiment’? 14 2.3 Oorzaken van de omslag in het Oosterschelde-beleid 16 Hoofdstuk 3: Vroeg protest tegen de afsluiting, 1953-1970 18 3.1 Actie van de visserij. ‘Geef ons geen Oosterschelde dam, ’t Gaat om des 19 vissers boterham!’ 3.2 De kritiek van wetenschappers: de Oosterschelde als ‘zinkput van Europa’ 23 3.3 Een teleurstellend Oosterschelde-congres 26 3.4 De Studiegroep Oosterschelde: overleg in plaats van ‘toestanden met stickers’ 28 3.5 De media over de Oosterschelde-kwestie 30 Hoofdstuk 4: De Oosterschelde-kwestie in de politiek, 1953-1970 32 4.1 Het Deltaplan in de Tweede Kamer: ‘offers’ voor bescherming tegen 32 de ‘erfvijand’ 4.2 Reacties van de politiek op het toenemend protest 33 4.3 Rijkswaterstaat: van aanzien en macht naar rumoer en kritiek 35 4.4 De tijdgeest van de jaren vijftig en zestig: ‘Stilte voor de storm, 37 maar niet windstil’ Conclusie: geen vloedgolf, maar stroomversnelling in de jaren zeventig 40 Literatuur 43 2 Inleiding In de nacht van 31 januari op 1 februari 1953 voltrok zich in Zuidwest-Nederland een ramp, waarbij met name de provincie Zeeland zwaar werd getroffen. -

Kabinetsformaties :§

DR. P.F. MAAS Kabinetsformaties 1959-1973 :§ Kabinetsformaties 1959-1973 Reeks Parlementaria 1 Dr. N. Cramei, Wandelingen door de handelingen 2 Dr. J. Kooiman, Over de Kamer gesproken 3 Dr. E. van Raalte, Het Nederlandse Parlement 4 Ir. E. Denig, Macht en informatie 5 Dr. P. F. Maas, Kabinetsformaties 1959-1973 Kabinetsformaties 1959-1973 M et een woord vooraf door dr. M. A. M. Klompé M et medewerking van mr. P. P. T. Bovend’Eert F. Lafort Drs. J. E. C. M. van Oerle Staatsuitgeverij, ’s-Gravenhage, 1982 Auteursrecht voorbehouden Ö Staatsuitgeverij,’s-Gravenhage 1982 Behoudens uitzondering door de Wet gesteld mag zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de rechthebbende(n) op het auteursrecht niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm of anderszins, hetgeen ook van toepassing is op de gehele of gedeeltelijke bewerking. De uitgever is met uitsluiting van ieder ander gerechtigd de door derden verschuldigde vergoedingen van kopiëren, als bedoeld in artikel 17 lid 2, Auteurswet 1912 en in het K.B. van 20 juni 1974 (Stb. 351) ex artikel 16b Auteurswet 1912, te innen en/of daartoe in en buiten rechte op te treden. Save exceptions stated by the law no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or other means, included a complete or partial transcription, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Only the publisher is qualified to collect the dues indebted by others for copying. ISBN 90 12 03998 3 Opgedragen aan wijlen In de week voor Pasen 1981 overleed prof. -

Large-Scale Offshore Wind Power in the United States ASSESSMENT of OPPORTUNITIES and BARRIERS

Large-Scale Offshore Wind Power in the United States ASSESSMENT OF OPPORTUNITIES AND BARRIERS September 2010 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors, in paper, from: U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062 phone: 865.576.8401 fax: 865.576.5728 email: mailto:[email protected] Available for sale to the public, in paper, from: U.S. Department of Commerce National Technical Information Service 5285 Port Royal Road Springfield, VA 22161 phone: 800.553.6847 fax: 703.605.6900 email: [email protected] online ordering: http://www.ntis.gov/ordering.htm Printed on paper containing at least 50% wastepaper, including 10% post consumer waste. -

Twee Miljoen Leden 3

Twee Over het verleden, de toekomst en het heden van de Nederlandse vakbeweging miljoenIn gesprek met 25 vakbondsvoorzitters ledenBert Breij Uitgave van de Vakbondshistorische Vereniging vvhvhv bboek_p01_02_HT.inddoek_p01_02_HT.indd 1 116-09-20086-09-2008 001:34:381:34:38 colofon © deze uitgave: Vakbondshistorische Vereniging, Amsterdam, 2008 © tekst: Bert Breij, Amsterdam, 2008 © illustraties: zie illustratie verantwoording basisontwerp: De Werksalon, Weesp uitwerking en productie: Kitty Molenaar, Amsterdam Deze uitgave kwam tot stand in samenwerking met Communication Concert in Weesp. ISBN EAN 978 90 71562 06 8 NUR 740 illustratie verantwoording AFMP: 211. Bert Janssen: 163. ANP: 17; 112. Martine Jansen: 221. Aob: 173. Ton Kastermans: 155. Paul Babeliowsky: 142. Ben van Meerendonk/IISG: 85 Roy Beusker: 195. Bas Meijer: 167. Eric Brinkhorst: 225. Bas Moerman: 231. CMHF: 207 Henk Nieuwenhuijs: 152; 159. CNV: 131. Opland/Pictoright: 89; 108; 113; 148. Ben Donkers: 217. Sem Presser/MAI: 101. Rafael Drent: 203. Prive collectie: 25; 27; 30; 40; 88; 104; 105; 106; 129; 138. Fotostudio André Ruigrok: 175. Han Singels: 109; 110; 135. Fotostudio De Bock: 161. Spaarnestad Photo Archief: 21; 47; 52; 56; 60; 70; 71;72; 73; 99; 143; Dijkema: 191. 193; 201; 222; 223; 230. Foto P&I: 229 Peter van Straaten/Van Lennep productiebos: 119. FNV: 149. Gerard Til: 123; 141. John de Haas: 98. Norbert Voskens: 187. Dirk Hol: 139; 147. Nelly Wuis: 199. Hollandse Hoogte: omslag; 124; 200; 213; 218. IISG: 4; 15; 19; 26; 32; 34; 36; 38 ; 39; 40; 41; 42; 43; 44; 45; 46; 48; 49; 50; 51; 53; 56; 57; 58; 59; 61; 62; 63; 64; 66; 67; 70; 74; 77; Met zorgvuldigheid hebben we getracht de rechthebbende te 78; 87; 103; 105; 107; 116; 127; 130; 136; 144, 145; 146; 150; 151; achterhalen. -

Rood 02-2008.Indd

RLedenblad van de Partijoo van de Arbeid • 5e jaargang • nummer d 2 • april 2008 THEMANUMMER KLIMAAT De kritiek van Vermeend op CO2-opslag en biomassa Minister Cramer: ‘Daadkracht belangrijker dan wetten’ Hoe het werkplan van het partijbestuur de koers versterkt Diederik Samsom: ‘Tegen de waanzin van een opblaasbare jacuzzi kunnen we niet op’ Diederik Samsom (36), woordvoerder Milieubeleid in de Tweede Kamer Sterk en sociaal Rood 02-2008.indd 1 20-03-2008 14:02:32 Tekst Anne Marie Zimmerman Foto Tessa Posthuma de Boer Frans de Loos wil graag iets aan de de rode loper maatschappij doen en niet blijven hangen De Rode Loper wordt uitgerold voor PvdA-ers die normaal gesproken in louter geklaag over dingen die niet achter de schermen werken. Meestal willen ze dat ook graag. Voor goed gaan. Hij heeft gekozen voor een een portret in Rood wordt deze keer een uitzondering gemaakt door bestuursfunctie in de politiek zodat hij Frans de Loos, penningmeester en voormalig voorzitter van de afdeling actie kan ondernemen. Geldermalsen en de regio Rivierenland. ‘Wat me aanspreekt in de politiek en met name in de lokale politiek, is dat je dingen toch serieus kunt veranderen. Volgens mij is dat in de regio Rivierenland ook best gelukt. Toen ik begon bij de afdeling Geldermalsen had- den we een partijbestuur van twee personen met dubbele functies. Op dit moment is het bestuur voltallig en worden er weer discussies gevoerd over thema’s die ons aanspreken. Je ziet dus dat er wat gebeurt. Wat ik eigenlijk doe is faciliteren, zodat degenen die inhoudelijk aan de politiek willen werken, daar meer tijd aan kunnen beste- den.