Libya: Five Years After Ghadafi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Strategy for Success in Libya

A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 A Strategy for Success in Libya Emily Estelle NOVEMBER 2017 AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE © 2017 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI) is a nonpartisan, nonprofit, 501(c)(3) educational organization and does not take institutional positions on any issues. The views expressed here are those of the author(s). Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Why the US Must Act in Libya Now ............................................................................................................................1 Wrong Problem, Wrong Strategy ............................................................................................................................... 2 What to Do ........................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Reframing US Policy in Libya .................................................................................................. 5 America’s Opportunity in Libya ................................................................................................................................. 6 The US Approach in Libya ............................................................................................................................................ 6 The Current Situation -

The 2016 U.S. Election

April 2017, Volume 28, Number 2 $14.00 The 2016 U.S. Election William Galston John Sides, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck James Ceaser Nathaniel Persily Charles Stewart III The Modernization Trap Jack Snyder The Freedom House Survey for 2016 Arch Puddington and Tyler Roylance Sheriff Kora and Momodou Darboe on the Gambia Thomas Pepinsky on Southeast Asia Nic Cheeseman, Gabrielle Lynch, and Justin Willis on Ghana’s Elections Kai M. Thaler on Nicaragua Sean Yom on Jordan and Morocco The End of the Postnational Illusion Ghia Nodia The 2016 U.S. Election Longtime readers will be aware that this is the first time the Journal of Democracy has ever devoted a set of articles to the situation of democracy in the United States. Our traditional focus has been on the problems and prospects of democracy in developing and postcommunist countries. In the introduction to the group of essays in our October 2016 issue entitled “The Specter Haunting Europe,” we explained why we felt we had to redirect some of our attention to the growing vulnerability of democracy in the West, and promised that we would not refrain from examining the United States as well. This is an especially delicate task for us because our parent organization, the National Endowment for Democracy, is a reso- lutely bipartisan institution that seeks to steer clear of the controversies of U.S. domestic politics. We hope we have succeeded in avoiding the pitfalls of partisanship; but in an era when the trends that are weakening liberal democracy are increasingly global, an editorial version of “Ameri- can isolationism” no longer seemed a defensible policy. -

Successes and Failures in the Enactment of Humanitarian Intervention During the Obama Administration

“THE ROAD TO HELL AND BACK”: SUCCESSES AND FAILURES IN THE ENACTMENT OF HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION DURING THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION A Thesis submitted to the FaCulty of the Graduate SChool of Arts and SCiences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in ConfliCt Resolution By Justine T. Robinson, B.A. Washington, DC DeCember 10, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Justine T. Robinson All Rights Reserved ii “THE ROAD TO HELL AND BACK”: SUCCESSES AND FAILURES IN THE ENACTMENT OF HUMANITARIAN INTERVENTION DURING THE OBAMA ADMINISTRATION Justine T. Robinson, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Andrew Bennett, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis examines how United States presidential administrations change over time in their poliCies on humanitarian intervention. More speCifiCally, how and why do AmeriCan presidential administrations (and the offiCials in those administrations) fail in some cases and sucCeed in others in enaCting ConfliCt resolution and genocide preventative measures? This thesis will focus on why offiCials in the two Obama administration sometimes used ambitious means of humanitarian intervention to prevent or mitigate genocide and other mass atrocities, as in the Cases of Libya and the Yazidis in Iraq, and sometimes took only limited steps to aChieve humanitarian goals, as in the case of the Syrian Civil War and Syrian refugees. This thesis is partiCularly interested in cases where earlier Obama administration aCtions and outComes forced the president and his advisors to rethink their approaCh to potential humanitarian intervention cases. The central hypothesis of this thesis is that poliCy changes on humanitarian intervention over time within U.S. -

The Failures of Intelligence Reform

Coastal Carolina University CCU Digital Commons Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Honors Theses Studies Fall 12-15-2012 The aiF lures of Intelligence Reform Amber Ciemniewski Coastal Carolina University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Ciemniewski, Amber, "The aiF lures of Intelligence Reform" (2012). Honors Theses. 52. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/honors-theses/52 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College and Center for Interdisciplinary Studies at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 were a devastating shock to the United States. They alerted Americans to the new threat of non-state actors. National Security had been severely damaged, and the new threat provoked the U.S. to enter into a problematic war in the Middle East region. Immediately after the attacks, the “blame game” began. Though there are seventeen organizations in the United States intelligence community, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) suffered the worst criticism for their roles in failing to prevent the attacks. The Bush administration established the 9/11 Commission in order to investigate what went wrong and to determine how to fix it. Based on the recommendations provided by the Commission, various organizations were changed and/or created in the intelligence community. Out of many changes, two were the most significant. -

Making Islam an American Religion

Religions 2014, 5, 477–501; doi:10.3390/rel5020477 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article Post-9/11: Making Islam an American Religion Yvonne Yazbeck Haddad 1,* and Nazir Nader Harb 2 1 The Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding, Georgetown University, 37th and O Streets, N.W., Washington, DC 20057, USA 2 Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies, Georgetown University, 1437 37th St, N.W., Washington, DC 20057, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-202-687-2575; Fax: +1-202-687-8376. Received: 3 January 2014; in revised form: 19 May 2014 / Accepted: 20 May 2014 / Published: 1210 June 2014 Abstract: This article explores several key events in the last 12 years that led to periods of heightened suspicion about Islam and Muslims in the United States. It provides a brief overview of the rise of anti-Muslim and anti-Islam sentiment known as “Islamophobia”, and it investigates claims that American Muslims cannot be trusted to be loyal to the United States because of their religion. This research examines American Muslim perspectives on national security discourse regarding terrorism and radicalization, both domestic and foreign, after 9/11. The article argues that it is important to highlight developments, both progressive and conservative, in Muslim communities in the United States over the last 12 years that belie suspicions of widespread anti-American sentiment among Muslims or questions about the loyalty of American Muslims. The article concludes with a discussion of important shifts from a Muslim identity politics that disassociated from American identity and ‘American exceptionalism’ to a position of integration and cultural assimilation. -

Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions

National Political Science Bee 2019-2020 Bee Round 3 Bee Round 3 Regulation Questions (1) This man assisted a black man in Detroit who was harassed for moving into an all-white neighborhood named Ossian Sweet. After the murder of Joseph Kahahawai, this man obtained a commutation for Socialite Grace Fortescue in the Massie Trial. This man defended two University of Chicago students who believed themselves to be the Ubermensch by having them plead guilty to the murder of Bobby Franks. He defended a teacher accused of violating the Butler Act against William Jennings Bryan. For the point, name this lawyer who defended Leopold and Loeb and John Scopes. ANSWER: Clarence Darrow (or Clarence Seward Darrow) (2) This agency's commissioner under FDR, John Collier, drew from his findings in the Meriam Report to advocate for legislation like the JohnsonO'Malley Act. This agency controversially administered boarding schools based on Richard Henry Pratt's Carlisle model. In 1972, 500 AIM protestors took over this agency's building in the culmination of their Trail of Broken Treaties walk. This agency within the U.S. Department of the Interior faced criticism for supporting Dick Wilson of the Oglala Dakota. For the point, name this agency that oversees 573 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native tribes. ANSWER: Bureau of Indian Affairs (or BIA) (3) The Paradise Papers implicated Odebrecht in paying bribes that were uncovered during this investigation. Lula da Silva was arrested as part of this investigation, and Gilmar Mendes ruled Lula couldn't become Chief of Staff to avoid prosecution. -

The Nature of Political Satire Under Different Types of Political

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Honors Program Theses Spring 2017 Laughing in the Face of Oppression: The aN ture of Political Satire Under Different Types of Political Regimes Victoria Villavicencio Pérez Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors Part of the Communication Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Villavicencio Pérez, Victoria, "Laughing in the Face of Oppression: The aN ture of Political Satire Under Different Types of Political Regimes" (2017). Honors Program Theses. 55. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors/55 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POLITICAL SATIRE UNDER DIFFERENT POLITICAL REGIMES 1 Laughing in the Face of Oppression: The Nature of Political Satire Under Different Types of Political Regimes Victoria Villavicencio Honors Degree Program POLITICAL SATIRE UNDER DIFFERENT POLITICAL REGIMES 2 Table of Contents ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................4 SIGNIFICANCE ............................................................................................................................................6 -

App. 1 United States Court of Appeals Submitted February 9, 2018

App. 1 United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Submitted February 9, 2018 Decided March 27, 2018 No. 17-5133 PATRICIA SMITH AND CHARLES WOODS, APPELLANTS V. HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON AND UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLEES ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia (No. 1:16-cv-01606) ----------------------------------------------------------------------- Larry E. Klayman was on the briefs for appellants. David E. Kendall, Katherine M. Turner, and Amy Saharia were on the brief for appellee Hillary Rodham Clinton. Jessie K. Liu, U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney’s Office, and Mark B. Stern and Weili J. Shaw, Attorneys, U.S. Department of Justice, were on the brief for appellee United States of America. Before: ROGERS, MILLETT, and PILLARD, Circuit Judges. App. 2 Opinion for the Court filed PER CURIAM. PER CURIAM: Sean Smith and Tyrone Woods tragically perished in the September 11, 2012, attacks on United States facilities in Benghazi, Libya. Their parents, Patricia Smith and Charles Woods, sued for- mer Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton for common-law torts based on her use of a private email server in conducting State Department affairs while Secretary of State and public statements about the cause of the attacks she made in her personal capacity while a presidential candidate. They appeal the substi- tution of the United States as the defendant on the claims involving the email server and the dismissal of their complaint for lack of subject matter jurisdiction and failure to state a claim. We affirm. I. The genesis of this case is in Clinton’s private meeting with Smith and Woods on September 14, 2012, in the wake of their sons’ deaths. -

Ansar Al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) Type Of

Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) Type of Organization: insurgent, non-state actor, religious, social services provider, terrorist, violent Ideologies and Affiliations: Islamist, jihadist, Qutbist, Salafist, Sunni, Takfiri Place(s) of Origin: Libya Year of Origin: 2012 Founder(s): Abu Sufyan Bin Qumu (founder of Ansar al-Sharia in Derna);1 Mohamed al-Zahawi, Nasser al-Tarshani, and other Libyan Islamists (founders of Ansar al-Sharia Benghazi) Place(s) of Operation: Libya Also Known As: • Ansar al-Charia in Libya 2 • Katibat Ansar al-Charia 3 • Katibat Ansar al-Sharia 4 • Partisans of Islamic Law in Libya5 • Partisans of Sharia in Libya 6 • Supporters of Islamic Law in Libya7 • Supporters of Sharia in Libya 8 Executive Summary: Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL) is a violent jihadist group that seeks to implement sharia (Islamic law) in Libya. ASL is the union of two smaller groups, the Ansar al-Sharia Brigade in Benghazi (ASB) and Ansar al-Sharia Derna (ASD), each formed in 2011 after the fall of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi’s regime. In 2012, ASB and ASD, 1 Aaron Y. Zelin, “Know Your Ansar Al-Sharia,” Foreign Policy, September 21, 2012, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/09/21/know_your_ansar_al_sharia. 2 “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Two Entities to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, November 19, 2014, http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11659.doc.htm. 3 “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Two Entities to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, November 19, 2014, http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11659.doc.htm. 4 “Security Council Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Two Entities to Its Sanctions List,” United Nations, November 19, 2014, http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/sc11659.doc.htm. -

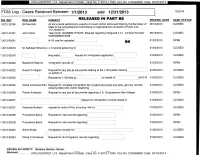

Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 RELEASED IN

UNCLASSIFIED U.S. Department of State Case No. F-2013-17945 Doc No. C05494608 Date: 04/16/2014 FOIA Log - Cases Received Between 1/1/2013 and 12/31/2013 1/2/2014 tEQ REF REQ_NAME SUBJECT RELEASED IN PART B6 RECEIVE DATE CASE STATUS 2012-26796 Bill Marczak All documents pertaining to exports of crowd control items submitted by the Secretary of 08/14/2013 CLOSED State to the Congressional Committees on Appropriations pursuant to Public Law 112-74042512 2012-31657 John Calvit Task Order: SAQMMA11F0233. Request regarding Vanguard 2.2.1. Contract Number: 08/14/2013 CLOSED GS00Q09BGF0048 L-2013-00001 H-1B visa for requester B6 01/02/2013 OPEN 2013-00078 M. Kathleen Minervino J-1 records pertaining to 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00218 Requestor request for immigration application 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00220 Bashist M Sharma immigration records of 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00222 Robert D Ahlgren Request for any and all documents relating to the 1-130 petition filed by 01/02/2013 CLOSED on behalf of F-2013-00223 Request for 1-130 filed 1.)- on behalf of NVC # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00224 Gloria Contreras Edin Request for complete immigration file including all entries and exits, and any records 01/02/2013 CLOSED showing false USC claims regarding F-2013-00226 Parker Anderson Request for any and all documents regarding U.S. Congressman Sam Steiger. 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00227 request for immigration records receipt # 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00237 Kayleyne Brottem request for entire A-File, including 1-94 for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00238 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00239 Providence Spina Request for visa records regarding 01/02/2013 OPEN F-2013-00242 Sonia Alcala Immigration records for 01/02/2013 CLOSED F-2013-00243 Gloria C Cardenas Request for all immigration records regarding 01/02/2013 CLOSED REVIEW AUTHORITY: Barbara Nielsen, Senior Reviewer UNCLASSIFIED U.S. -

Proposed Additional Views of Representatives Jim Jordan and Mike Pompeo Summary of Conclusions I

EMBARGOED UNTIL 6/28/12 @ 5:00 AM PROPOSED ADDITIONAL VIEWS OF REPRESENTATIVES JIM JORDAN AND MIKE POMPEO SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS I. The First Victim of War is Truth: The administration misled the public about the events in Benghazi Officials at the State Department, including Secretary Clinton, learned almost in real time that the attack in Benghazi was a terrorist attack. With the presidential election just 56 days away, rather than tell the American people the truth and increase the risk of losing an election, the administration told one story privately and a different story publicly. They publicly blamed the deaths on a video-inspired protest they knew had never occurred. II. Last Clear Chance: Security in Benghazi was woefully inadequate and Secretary Clinton failed to lead The State Department has many posts but Libya and Benghazi were different. After Qhaddafi, the U.S. knew that we could not count on host nation security in a country where militias held significant power. The American people expect that when the government sends our representatives into such dangerous places they receive adequate protection. Secretary Clinton paid special attention to Libya. She sent Ambassador Stevens there. Yet, in August 2012, she missed the last, clear chance to protect her people. III. Failure of Will: America did not move heaven and earth to rescue our people The American people expect their government to make every effort to help those we put in harm’s way when they find themselves in trouble. The U.S. military never sent assets to help rescue those fighting in Benghazi and never made it into Libya with personnel during the attack. -

Legislative and Executive Branch Initiatives

Securing U.S. Diplomatic Facilities and Personnel Abroad: Legislative and Executive Branch Initiatives Alex Tiersky Analyst in Foreign Affairs December 23, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43195 Securing U.S. Diplomatic Facilities and Personnel Abroad Summary The September 11, 2012, attack on U.S. facilities in Benghazi, Libya, prompted sustained congressional attention on the specific circumstances of the events in question, as well as broader questions regarding how U.S. diplomatic personnel and facilities abroad are secured. Ensuring that the Department of State is better prepared for the possibility of similar attacks in the future has been a central congressional concern. The Department of State undertook a number of measures in response to the attack, including immediate steps to bolster security at posts around the world; an investigation of the incident through an Accountability Review Board; and longer-term measures implementing the board’s recommendations, including requests for significantly greater funding than in recent years. Congress has conducted oversight through investigations by a number of committees and through a number of hearings. The House of Representatives voted to create a select committee on the Benghazi attack on May 8, 2014; the committee held its first hearing on September 17, 2014. Members have also put forward legislative proposals on issues ranging from the composition of Accountability Review Boards to procedures for awarding local security guard force contracts. In the 113th Congress, two wide-ranging bills incorporating many of these areas have been considered: H.R. 2848, the Department of State Operations and Embassy Security Authorization Act, Fiscal Year 2014, and S.