Re-Engineering the Skill Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Stapp) Skill Development and Employment

NISTADS Tracks in Policy Research: NISTADS/NTPR/STAPP/Skills/2019/1 CSIR–National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies S&T applicaTionS To peopleS’ problemS (STAPP) Skill Development and Employment P. Goswami Praveen Sharma 1 Page CSIR-NISTADS- STAPP/Drinking Water Project Information Project Team: Nodal Officer : Dr. P. Goswami Principal Investigator : Dr. Praveen Sharma Funding Agency: CSIR Publication Type: Interim Report Circulation: Limited Corresponding Author: P Goswami; [email protected] Acknowledgement: This Policy Advocacy benefitted from comments from a variety of sources, especially from CSIR laboratories. The analyses presented are based on mostly secondary sources (websites); while we have made sincere efforts to refer to all these sources, it is possible we have missed some. Finally, the critical comments on our earlier drafts from several reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. Disclaimer: The report is largely is descriptive in nature. It is based on secondary data and information composed from the related sources like reports, research papers and books. Also documents of various ministries/departments, organizations and information from many web-sites have been used. The internet data and information referenced in this report were correct, to the best of the knowledge, at the time of publication. Due to the dynamic nature of the internet, resources that are free and publicly available may subsequently require a fee or restrict access, and the location of items may change as menus and webpages are reorganized. 2 Page S &T applicaTionS To peopleS’ problemS (stapp): an ouTline The Prime Minister of India had on several occasions emphasized the need for addressing problems faced by the people of India, through S&T applications. -

Transforming India Through Make in India, Skill India and Digital India

through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & 1 through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & 2 through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & 3 through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & From President’s Desk We envisage a transformed India where the economy is in double digit growth trajectory, manufacturing sector is globally competitive, the agriculture sector is sufficient to sustain the rising population and millions of jobs are created for socio-economic development of the Dr. Mahesh Gupta nation. This transformation will take place through the dynamic policy environment announced by our esteemed Government. The policies like Make in India, Skill India and Digital India have the potential to “India has emerged as the boost not only economic growth but overall socio-economic development of the country to the next level. The inclusive one of the fastest moving development of the country would pave the way for peace, progress economies and a leading and prosperity. investment destination. The fact is that ever since India I believe, the economic activity is expected to regain its momentum in has launched dynamic the coming months with circulation of new currency in the system that reforms there has been no would lead to reduction in interest rates and higher aggregate demand. looking back. ” The theme of our 111th AGM is “Transforming India through Make in India, Skill India & Digital India’. The transformed India provide housing for all, education for all, easy access to medical and health facilities as well as safe and better standards of living to the population of India. Transformed India would promise every citizen to realize his or her potential and contribute towards self, family and the country. -

SKILL INDIA 1. Introduction Skill Development Is an Important Driver

National Paper - PLP – 2019-20 SKILL INDIA 1. Introduction Skill development is an important driver to address poverty reduction by improving employability, productivity and helping sustainable enterprise development and inclusive growth. India is facing a paradoxical situation, where on the one hand, youth entering the labour market have no jobs; on the other hand, industries are complaining of unavailability of appropriately skilled manpower. The employment sector in India poses great challenge in terms of its structure which is dominated by informal workers, high levels of under employment, skill shortages and labour markets with rigid labour laws and institutions. Vocational education and training are crucial for enhancing the employability of an individual, by facilitating the individual’s transition into the labour market. The present skilled workforce in India is only 2 %, much lower than the developing nations (Korea (96%), Japan (80%), Germany (75%), UK (68%) and China (40%) as reported by Labour Bureau report. As compared to other developed and developing countries, India has a unique window of opportunity for another 20-25 years called the “demographic advantage”. If India is able to skill its people with the requisite life skills, job skills or entrepreneurial skills in the years to come, the demographic advantage can be converted into the dividend wherein those entering labour market or are already in the labour market contribute productively to economic growth both within and outside the country. Keeping in view that 93% of the total labour force is in the unorganised sector, the major challenge of skill development initiatives is to address the needs of a vast population by providing them skills which would make them employable and enable them to secure decent work leading to improvement in the quality of their life. -

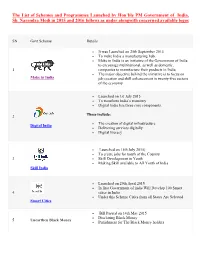

The List of Schemes and Programmes Launched by Hon'ble PM Government of India, Sh. Narendra Modi in 2015 and 2016 Follows As

The List of Schemes and Programmes Launched by Hon’ble PM Government of India, Sh. Narendra Modi in 2015 and 2016 follows as under alongwith concerned available logos SN Govt Scheme Details It was Launched on 25th September 2014 To make India a manufacturing hub. Make in India is an initiative of the Government of India to encourage multinational, as well as domestic, 1 companies to manufacture their products in India. The major objective behind the initiative is to focus on Make in India job creation and skill enhancement in twenty-five sectors of the economy Launched on 1st July 2015 To transform India’s economy Digital India has three core components. These include: 2 The creation of digital infrastructure Digital India Delivering services digitally Digital literacy Launched on 15th July 2015) To create jobs for youth of the Country 3 Skill Development in Youth Making Skill available to All Youth of India Skill India Launched on 29th April 2015 In first Government of india Will Develop 100 Smart 4 cities in India Under this Scheme Cities from all States Are Selected Smart Cities Bill Passed on 14th May 2015 Disclosing Black Money 5 Unearthen Black Money Punishment for The Black Money holders SN Govt Scheme Details Namami Gange Project or Namami Ganga Yojana is an ambitious Union Government Project which integrates the efforts to clean and protect the Ganga river in a comprehensive manner. It its maiden budget, the government announced Rs. 2037 Crore towards this mission. 6 The project is officially known as Integrated Ganga Conservation Mission project or ‘Namami Ganga Namami Gange Yojana’. -

Skill Development

VISIONIAS www.visionias.in Skill Development Table of Content 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Skill in India: Current Scenario ................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Why India needs Skill Development? ..................................................................................................................... 2 4. Why India lacks skilled workforce? – Challenges and Issues .................................................................................. 3 5. Major Skill Development Institutions ..................................................................................................................... 4 5.1. Ministry of Skill Development ......................................................................................................................... 4 5.2. National Skill Development Corporation ......................................................................................................... 4 6. Recent Steps taken by government........................................................................................................................ 4 6.1.1 National Skill Development Mission .............................................................................................................. 4 6.1.2 Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana .......................................................................................................... -

National E-Governance Division Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology Govt

National e-Governance Division Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology Govt. of India No. N-21/15/2020-NeGD-MeitY Dated: 9th April 2021 Expression of Interest (EOI) for agent assisted service delivery of UMANG services on non-exclusive basis UMANG mobile app was dedicated to the nation by Hon’ble Prime Minister on 23rd Nov. 2017. UMANG provides single point access to 1,000+ services of Centre and 29 State Governments and 19000+ bill payment services through Mobile. UMANG has been downloaded ~4 Crore times and witnessing ~2-3 million transactions per day and ~30,000- 40,000 new user registrations per day. Having created UMANG Mobile App with vast number of services, NeGD, MeitY now wants to extend these services in ‘Assisted Mode’ to citizens not having smart phone or not able to use Mobile app on smart phones. NeGD is already providing UMANG services in ‘Assisted mode’ through CSCs and now wants to partner with more such entities. Accordingly NeGD seeks expression of interest from interested Indian companies/entities which are incorporated in India with majority stake with Indian citizens for providing select UMANG Services through agents or Human Assisted Platform on non- exclusive basis. Initial list of about ~500 such services is attached. The interested entities may submit their EOI proposal for consideration by NeGD to Neeraj Kumar, Director (UMANG), National e Governance Division (NeGD), 4th Floor, Electronics Niketan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 and mail copy can be sent to [email protected] (Ph: 011-24303703). NeGD will scrutinize the received proposals and will come out with a Policy/RFP having suitable eligibility criterion and commercial conditions. -

6Th Smart Cities India 2020 Expo Including

6th Smart Cities India 2020 Expo Including Developing Smart Cities for our Citizens PRAGATI MAIDAN, NEW DELHI | 20-22 MAY 2020 Co-Organiser Organiser www.smartcitiesindia.com EXPO Smart Tech with • Launched in 2015, the Smart Cities India expo is a leading international expo India’s Urban Planning • Organised with the India Trade Promotion Organisation (ITPO) • The 3-day expo attracts 400+ exhibitors • Number of visitors has increased to 16,000+ in 2019 and is growing CONFERENCE • 40+ conference sessions and workshops with 250+ speakers • Includes representatives from the Centre and States, PSUs, officials, diplomats, commissioners, mayors, city leaders, private sector, professionals, academics, etc SPECIAL EVENTS Mission Achievements: Some examples • City Leaders Conclave • Smart Cities: A total of 5,151 projects costing $29.5 billion have been sanctioned • EV & Battery Tech Summit across 100 cities. • Mobi Colloquium • FY 2018-19: Over 2,300 projects worth around $13.1 billion tendered • Smart Cities India Awards • AMRUT: 482 cities selected; 4,097 projects awarded at an outlay of $7.1 billion • Smart Village Conclave from FY 15-16 to FY 19-20 including water supply projects, sewerage and septage • Solar Rooftop Summit management; storm water drainage; non-motorised urban transport, and parks/ • Start-up India Pavilion green spaces in 500 cities • National Electric Mobility Mission: Department of Heavy Industries (DHI) introduced Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid & Electric Vehicles in India MISSIONS INCLUDED (FAME-India) scheme in 2015. Financial support provided to 261,507 electric/hybrid vehicles to date • Smart Cities Mission • Fully electric buses added to the scheme for modernising the public transport • National Solar Mission system in Oct 2017; DHI has sanctioned 455 electric buses for 9 cities with 44 more • National Water Mission cities seeking 3144 e-buses • National Electric Mobility • National Solar Mission: A cumulative of 28,780 MW solar capacity installed uptill Mission 31st March 2019. -

India's Smart Cities Mission

INDIA’S SMART CITIES MISSION SMART FOR WHOM? CITIES FOR WHOM? UPDATE 2018 HOUSING AND LAND RIGHTS NETWORK Housing and Land Rights Network, India 1 GREEN PUBLIC PROCUREMENT GREEN PUBLIC PROCUREMENT: Policy and Practice within the European Union and India Authors: Ms Barbara Morton, Mr Rajan Gandhi Reviewed by: Mr Wandert Benthem and Dr Johan Bentinck (Euroconsult Mott MacDonald) Copy Editing by: Mr Surit Das Refer to the document on the project website (http://www.apsfenvironment.in/) for the hyperlinked version. Further information Euroconsult Mott MacDonald: www.euroconsult.mottmac.nl, www.mottmac.com Information about the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (www.europa.eu) and the website of the Delegation of the European Union to India Suggested(http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/india/index_en.htm). Citation: India’s Smart Cities Mission: Smart for Whom? Cities for Whom? [Update 2018], HousingLegal notices: and Land Rights Network, New Delhi, 2018 European Union LeadThis publicationContributors: has Shivani been producedChaudhry, with Swapnil the assistance Saxena, and of Deepakthe European Kumar Union. The content of Additionalthis publication Inputs: is theAishwarya sole responsibility Ayushmaan of the Technical Assistance Team and Mott MacDonald in Researchconsortium Assistance: with DHI and Madhulika can in no Masih way be and taken Salman to reflect Khan the views of the European Union or the Delegation of the European Union to India. Published by: HousingMott MacDonald and Land Rights Network G-18/1This document Nizamuddin is issued West for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the captioned project only. -

Government Support for Entrepreneurship Development

Government Support for Entrepreneurship Development • Initiatives for Start-up India • Stand up India and Skill India • Government of Gujarat schemes for Start-up • Start-up and ecosystem • Stand-up India: Women and Minority Entrepreneurship • Ease of Doing Business (EoDB) – Overview, Ranking, – Determinants of EoDB Government of India Support for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in India • The Government of India has undertaken several initiatives and instituted policy measures to foster a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship in the country. • In the recent years, a wide spectrum of new programmes and opportunities to nurture innovation have been created by the Government of India across a number of sectors. • From engaging with academia, industry, investors, small and big entrepreneurs, non-governmental organizations to the most underserved sections of society. Government of India Support for Innovation and Entrepreneurship in India • Recognising the importance of women entrepreneurship and economic participation in enabling the country’s growth and prosperity, Government of India has ensured that all policy initiatives are geared towards enabling equal opportunity for women. • The government seeks to bring women to the forefront of India’s entrepreneurial ecosystem by providing access to loans, networks, markets and trainings. Efforts at promoting entrepreneurship and innovation 1. Startup India 2. Make in India 3. Atal Innovation Mission (AIM) 4. Support to Training and Employment Programme for Women (STEP) 5. Jan Dhan- Aadhaar- Mobile (JAM) 6. DigitalIndia 7. Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC) 8. Department of Science and Technology (DST) 9. Stand-Up India 10. Trade related Entrepreneurship Assistance and Development (TREAD) 11. Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) 12. -

GOVERNMENT SCHEMES & PROGRAMMES •Restructured Classification of Schemes (2016)

GOVERNMENT SCHEMES & PROGRAMMES •Restructured classification of Schemes (2016) 1. Central Sector Schemes (Fully funded by Central Government) 2. Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Jointly funded by Centre & States) 3. State Level Schemes (Fully funded by States) Core of the Core Schemes: 1. National Social Assistance Programme. 2. Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme 3. Umbrella Scheme for Development of Scheduled Castes 4. Umbrella Programme for Development of Scheduled Tribes 5. Umbrella Programme for Development of Minorities 6. Umbrella Programme for Development of Other Vulnerable Groups 1. Garib Kalyan Rojgar Abhiyaan • 20th June 2020. • Migrant workers & rural citizens who returned to their home states during Covid-19 lockdown. • Mission mode for 125 days with an outlay of Rs. 50,000 crore. • Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Odisha • 12 different Ministries/Departments will be coordinating for the implementation of the scheme. Question. Q. Which among the following statements is not correct about Garib Kalyan Rojgar Yojana. a) It is a mission mode Abhiyan implemented in all states with special focus on Aspirational Districts. b) Villages can join through Common Service Centers & Krishi Vigyan Kendras. c) Niti Ayog has been trusted with ensuring the focused implementation of program across 27 Aspirational Districts. d) Ministry of Rural Development is nodal Ministry for scheme. • Malnutrition was the primary reason behind 69 % of deaths of children below the age of five in India, according to a UNICEF’s The State of the World’s Children 2019 report. Stunting – 35% : Wasting – 17% : Overweight – 2%. • Global Nutrition Report 2020,- India likely to miss Global nutrition target by 2025. -

Skill Development Mission in India- a Step Towards Governance and Effectiveness

Global Journal of Enterprise Information System DOI: 10.18311/gjeis/2018/21322 Skill Development Mission in India- A Step towards Governance and Effectiveness Satendra Kumar Yadav* Institute of Business Management, GLA University, Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India; [email protected] Abstract Skill development plays a significant role in contributing to the growth process of a country. It has more significance in particular to a fast growing economy like India. The demographic transition makes it imperative to generate employment opportunities for more than 12 million youths adding to working age population every year. According to the reports available, it is estimated that during the period of 2005-2012, only 2.7 million net additional jobs were created in India. Skill development is an essential requirement to develop youth and enable them to engage in useful vocations in the future. In India, the governments have been making policies and providing neces- sary support for skill development through various schemes not only by providing training and managerial skills but also the financial assistance through various channels. However, the success rate of the initiatives and pace of growth of skill development have not been that much encouraging in the past. The present government has taken this mission altogether in a different dimension by expanding the facilities and supports in a big way. This paper presents the present status of the programmes being implemented by the govern- ment of India for enthusing skill development in true spirit through various schemes. A separate body to monitor and regulate the Skill Keywords: development Mission has been constituted known as National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC). -

Entrepreneur and Startup Policy 2017

ANNEXURE-‘X’ Entrepreneur and Startup Policy 2017 Entrepreneur and Startup Policy 2017 A Foreword by Chief Minister For last 3 three years, we at Haryana government have been working along with Central Government, to develop an Ecosystem for Social and Economic growth. Various landmark reforms have been initiated to support all the sectors with special focus on Startups, as these sectors have the potential to solve the social and economic issues through innovative ideas and generate a plethora of employment opportunities. Haryana provides “Entrepreneurs & Startups” access to a mature IT, Infrastructure, Manufacturing, Agriculture and Services Industry. Entrepreneur and Startup Policy of Haryana has been prepared keeping in view the teething problems faced by the Entrepreneurs. Various initiatives such as formation of Incubation Cells, Fiscal Incentives, Seed Funding, Student Entrepreneurship and Policy relaxation, have been provided in the Startup Policy. I would like the young generation and budding Entrepreneurs to take advantage of the provisions made in the “Entrepreneur and Startup” policy and resolve issues in the field of healthcare, education, social infrastructure of the community. In line with the PM’s ‘Startup India Policy’, this policy aims to foster entrepreneurship and promote innovation by creating an ecosystem that is conducive for growth of Start-ups. Further, I am sure “Entrepreneur and Startup” policy of Haryana would help promote FDI and put Haryana on the Global Map Shri Manohar Lal Chief Minister Haryana 2 Entrepreneur and Startup Policy 2017 Foreword by Principal Secretary, IT Identification of untapped demand and underdeveloped markets, has given opportunities to various Entrepreneurs in India to launch new Business Platforms.