India's Smart Cities Mission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIGITAL INDIA CORPORATION a Section 8 Company, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Govt

Advt. No. N-21/49/2021-NeGD DIGITAL INDIA CORPORATION A section 8 Company, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, Govt. of India Delhi Office: Electronics Niketan Annexe, 6 CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi - 110003 Tel.: +91 (11) 24360199 / 24301756 Website: www.dic.gov.in WEB ADVERTISEMENT 18th August 2021 Digital India Corporation has been set up by the ‘Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology, Government of India’, to innovate, develop and deploy ICT and other emerging technologies for the benefit of the common man. It is a ‘not for profit’ Company under Section 8 of the Companies Act 2013. The Company has been spearheading the Digital India programme of the Government of India, and is involved in promoting use of technology for e-Governance, e-Health, Telemedicine, e-agriculture, e-Payments etc. The Digital India programme promotes safety and security concerns of growing cashless economy and addresses challenges confronting its wider acceptance. It also promotes innovation and evolves models for empowerment of citizens through Digital initiatives and promotes participatory governance and citizen engagement across the government through various platforms including social media. Digital India Corporation is currently inviting applications for the following position for covering fixed project duration purely on Contract/ Consolidated basis. Sr. Name of the Positions No of Qualifications and Experiences Salary per Month No. Vacancies (All Inclusive) 1. Consultant/ Lead Business 01 Graduation /B.E/ B. Tech. Commensurate to Analyst (mandatory) and M. Tech. /MBA Qualifications, Skills (desirable) and Experience Qualification can be relaxed in case of exceptional candidates 2. Business Analyst 03 Graduation/B.E/B. -

Solar Plus Energy Storage System at Dahod, Gujarat Traction Sub-Station by Indian Railways

SOLAR PLUS ENERGY STORAGE SYSTEM AT DAHOD, GUJARAT TRACTION SUB-STATION BY INDIAN RAILWAYS 11, January 2021 Submitted to Tetra Tech ES, Inc. (DELETE THIS BLANK PAGE AFTER CREATING PDF. IT’S HERE TO MAKE FACING PAGES AND LEFT/RIGHT PAGE NUMBERS SEQUENCE CORRECTLY IN WORD. BE CAREFUL TO NOT DELETE THIS SECTION BREAK EITHER, UNTIL AFTER YOU HAVE GENERATED A FINAL PDF. IT WILL THROW OFF THE LEFT/RIGHT PAGE LAYOUT.) SOLAR PLUS ENERGY STORAGE SYSTEM AT DAHOD, GUJARAT TRACTION SUB- STATION BY INDIA RAILWAYS Prepared for: United States Agency for International Development (USAID/India) American Embassy Shantipath, Chanakyapuri New Delhi-110021, India Phone: +91-11-24198000 Submitted by: Tetra Tech ES, Inc. A-111 11th Floor, Himalaya House, K.G. Marg, Connaught Place New Delhi-110001, India Phone: +91-11-47374000 DISCLAIMER This report is prepared for the M/s Tetra Tech ES, Inc. for the ‘assessment of the Vendor Rating Framework (VRF)’. This report is prepared under the Contract Number AID-OAA-I-13-00019/AID- OAA-TO-17-00011. DATA DISCLAIMER The data, information and assumptions (hereinafter ‘data-set’) used in this document are in good faith and from the source to the best of PACE-D 2.0 RE (the program) knowledge. The program does not represent or warrant that any dataset used will be error-free or provide specific results. The results and the findings are delivered on "as-is" and "as-available" dataset. All dataset provided are subject to change without notice and vary the outcomes, recommendations, and results. The program disclaims any responsibility for the accuracy or correctness of the dataset. -

Improving Consumer Voices and Accountability in the Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) Findings from the Benchmarking Citizen Report Cards in Odisha and Tamil Nadu CRC-2

Improving Consumer Voices and Accountability in the Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) Findings from the benchmarking Citizen Report Cards in Odisha and Tamil Nadu CRC-2 Conducted By For Project Supported by June 2017 Public Affairs Foundation (PAF) Implementation of Citizen Report Card (CRC-2) as a part of Improving Consumer Voices and Accountability in Swachh Bharat Mission (Gramin) [SBM(G)] Report of Findings Submitted to Public Affairs Centre (PAC) [For Feedback please contact Meena Nair at [email protected]] June 2017 [page left blank] i Public Affairs Foundation | CRC-2 in Tamil Nadu and Odisha | PAC/BMGF | June 2017 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ viii Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................. ix Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Report Outline ...................................................................................................................................... 10 Section 2: Methodology ........................................................................................................................ 11 Section -

Lessons from the Swachh Bharat Mission – Driving Behaviour Change at Scale

The making of “Swachh” India Lessons from the Swachh Bharat Mission – driving behaviour change at scale October 2018 KPMG.com/in © 2018 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Foreword The Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), which is perhaps the largest behaviour change campaign ever, aims to make India a clean nation. There is enough evidence to show that India is on a new trajectory of growth owing to the achievements under the mission. SBM has witnessed a phenomenal increase in rural sanitation coverage from 39 per cent to 90 per cent in the last four years. It is heartening to see the people of our nation stepping beyond their roles as mere beneficiaries of the programme to becoming its leaders. The large majority of citizens in rural India, especially the women, no longer have to suffer the indignity of having to go out into the open to defecate. In fact, women are becoming the primary force in driving the nation in becoming free from open defecation. It marks a sea change in their attitude which has a direct impact on their dignity and quality of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) believes that SBM could prevent about 300,000 deaths due to water borne diseases assuming we achieve 100 per cent coverage by October 2019. The credit for this will go to every Indian who was part of this campaign. I take this opportunity to congratulate the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation and every citizen in the country for catalysing the achievements achieved thus far. -

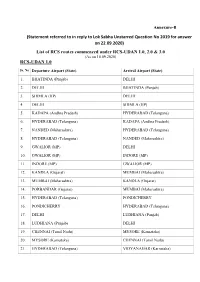

(Statement Referred to in Reply to Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No 2019

Annexure-B (Statement referred to in reply to Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No 2019 for answer on 22.09.2020) List of RCS routes commenced under RCS-UDAN 1.0, 2.0 & 3.0 (As on 16.09.2020) RCS-UDAN 1.0 Sr. No Departure Airport (State) Arrival Airport (State) 1. BHATINDA (Punjab) DELHI 2. DELHI BHATINDA (Punjab) 3. SHIMLA (HP) DELHI 4. DELHI SHIMLA (HP) 5. KADAPA (Andhra Pradesh) HYDERABAD (Telangana) 6. HYDERABAD (Telangana) KADAPA (Andhra Pradesh) 7. NANDED (Maharashtra) HYDERABAD (Telangana) 8. HYDERABAD (Telangana) NANDED (Maharashtra) 9. GWALIOR (MP) DELHI 10. GWALIOR (MP) INDORE (MP) 11. INDORE (MP) GWALIOR (MP) 12. KANDLA (Gujarat) MUMBAI (Maharashtra) 13. MUMBAI (Maharashtra) KANDLA (Gujarat) 14. PORBANDAR (Gujarat) MUMBAI (Maharashtra) 15. HYDERABAD (Telangana) PONDICHERRY 16. PONDICHERRY HYDERABAD (Telangana) 17. DELHI LUDHIANA (Punjab) 18. LUDHIANA (Punjab) DELHI 19. CHENNAI (Tamil Nadu) MYSORE (Karnataka) 20. MYSORE (Karnataka) CHENNAI (Tamil Nadu) 21. HYDERABAD (Telangana) VIDYANAGAR (Karnataka) Sr. No Departure Airport (State) Arrival Airport (State) 22. VIDYANAGAR(Karnataka) HYDERABAD (Telangana) 23. BIKANER (Rajasthan) DELHI 24. DELHI BIKANER (Rajasthan) 25. JAIPUR (Rajasthan) JAISALMER (Rajasthan) 26. JAISALMER (Rajasthan) JAIPUR (Rajasthan) 27. CHENNAI (Tamil Nadu) KADAPA (Andhra Pradesh) 28. KADAPA (Andhra Pradesh) CHENNAI (Tamil Nadu) 29. MUMBAI (Maharashtra) NANDED (Maharashtra) 30. NANDED(Maharashtra) MUMBAI (Maharashtra) 31. AGRA (UP) JAIPUR (Rajasthan) 32. JAIPUR (Rajasthan) AGRA (UP) 33. AHMEDABAD (Gujarat) JAMNAGAR (Gujarat) 34. JAMNAGAR (Gujarat) AHMEDABAD (Gujarat) 35. AHMEDABAD (Gujarat) MUNDRA (Gujarat) 36. MUNDRA (Gujarat) AHMEDABAD (Gujarat) 37. AHMEDABAD(Gujarat) DIU 38. DIU AHMEDABAD(Gujarat) 39. BANGALORE (Karnataka) VIDYANAGAR (Karnataka) 40. VIDYANAGAR (Karnataka) BANGALORE (Karnataka) 41. KADAPA (Andhra Pradesh) VIJAYWADA (Andhra Pradesh) 42. -

Privacy Gaps in India's Digital India Project

Privacy Gaps in India’s Digital India Project AUTHOR Anisha Gupta EDITOR Amber Sinha The Centre for Internet and Society, India Designed by Saumyaa Naidu Shared under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license Introduction Scope The Central and State governments in India have been increasingly taking This paper seeks to assess the privacy protections under fifteen e-governance steps to fulfill the goal of a ‘Digital India’ by undertaking e-governance schemes: Soil Health Card, Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & Systems schemes. Numerous schemes have been introduced to digitize sectors such as (CCTNS), Project Panchdeep, U-Dise, Electronic Health Records, NHRM Smart agriculture, health, insurance, education, banking, police enforcement, Card, MyGov, eDistricts, Mobile Seva, Digi Locker, eSign framework for Aadhaar, etc. With the introduction of the e-Kranti program under the National Passport Seva, PayGov, National Land Records Modernization Programme e-Governance Plan, we have witnessed the introduction of forty four Mission (NLRMP), and Aadhaar. Mode Projects. 1 The digitization process is aimed at reducing the human The project analyses fifteen schemes that have been rolled out by the handling of personal data and enhancing the decision making functions of government, starting from 2010. The egovernment initiatives by the Central the government. These schemes are postulated to make digital infrastructure and State Governments have been steadily increasing over the past five to six available to every citizen, provide on demand governance and services and years and there has been a large emphasis on the development of information digital empowerment. 2 In every scheme, personal information of citizens technology. Various new information technology schemes have been introduced are collected in order to avail their welfare benefits. -

District Health Society, Gumla Selected List for ANM MTC Adv

District Health Society, Gumla Selected List for ANM MTC Adv. At State O3lz0ts Total No of Post -08 Applicant Father's/Husband's Sl. No. Address Name Name t 2 3 4 Vill- Kapri,Po- Kumhari,Po+Ps- Basia Dt- t Rani Kumari Gokulnath Sahu Gumla,835229 2 Nutan Kumari Banbihari Sahu Vill+Po-Baghima,Ps-Palkot, Dt-Gum1a,835207 3 Sandhya Kurhari Mahesh Sahu Turunda,Po- Pokla gate,Ps-Kamdara,Dt- Gumla Vill-Kamdara,Tangratoli,Po+Ps- Kamdara,Dt- 4 Radhika Topno Buka Topno Gumla,835227 5 Rejina Tirkey Joseph Tirkey Vill+Po- Telgaon,Ps+Dt= Gumla,835207 6 Kiran Ekka Alexander Ekka Vill- Pugu karamdipa, Ps+Po- Gumla,835207 7 Rachna Rachita Bara Rafil Bara Vill- Tarri dipatoli,Po+Ps-Gum1a,835207 C/O Balacius Toppo,Vill-Sakeya,Po- Lasia,Ps- Basia, 8 Albina Toppo Balacius Toppo Dt- Grrmla F.?,\)11 District Health Society, Gumla Selected List for ANM - RBSK Adv. At State level OSl2OLs Total No of post - 22 Applicant Father's/Husband's Sl.No Address Name Name ,], 2 4 5 Vill- Kapri, P.O- Kumhari, P.S- Basia, Gumla 1, Rani Kumari Gokulnath Sahu 835229 Vill- Soso Kadam Toli, P.O+P.S+Dist-Gumla, 2 Jayanti Tirkey Hari Oraon 83s207 Vill+P.O- Baghima, P.S- Palkot, Gumla, 3 Nutan Kumari Ban Bihari Sahu 835207 Vill- Loyola Nagar, Gandhi Nagar, 4 Saroj Kumari Raghu Nayak P.O+P.S+Dist- G u mla, 835207 Vill- Sakya, P.O- Lasiya, P.S- Basia, Gumla, Teresa Lakra Gabriel Lakra 5 83s211 W/O- Syamsundar Thakur, Laxman Nagar, 6 Rajni Kumari Shyam Prasad Thakur P.O+P.S+Dist- G u m la, 835207 Vill- Puggu, Daud Nagar, P.O- Armai, 7 Rina Kumari Minz Gana Oraon P.S+Dist- Gu m la, -

National Guidelines for Smart Cities in India

GCI Thematic Round Table: A Dialogue on Smart Cities, June 29th, 2015 National Guidelines for Smart Cities in India Bharat Punjabi Post Doctoral Fellow, Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance, University of Toronto Visiting Fellow, Global Cities Institute, University of Toronto Email: [email protected] Major Objectives of the Smart Cities Mission • Retrofitting – providing services to those city pockets which are deficient in them • Redevelopment – reconstruction of those city pockets where other interventions are unlikely to bring improvements • City-wide improvements such as Intelligent Transport Solutions, and greenfield smart cities Excerpt from the Guidelines: Brownfield and Green field “ The purpose of the Smart Cities Mission is to drive economic growth and improve the quality of life of people by enabling local area development and harnessing technology, especially technology that leads to Smart outcomes. Area-based development will transform existing areas (retrofit and redevelop), including slums, into better planned ones, thereby improving liveability of the whole City. New areas (greenfield) will be developed around cities in order to accommodate the expanding population in urban areas. Application of Smart Solutions will enable cities to use technology, information and data to improve infrastructure and services ” The core infrastructure elements in a Smart City would include: • Adequate water supply, • Assured electricity supply, • Sanitation, including solid waste management, • Efficient urban mobility and public transport, • Affordable housing • Robust IT connectivity and digitalization, • Good governance, especially e-Governance and citizen participation, • Sustainable environment, • Safety and security of citizens, particularly women, children and the elderly, and • Health and education Finance and Urban Governance: Centre- State co-operation • Rs. -

Nutrition Situation and Stakeholder Mapping

This report compiles secondary data on the nutrition situation and from a stakeholder mapping in Pune, India to inform the new partnership between Birmingham, UK and Pune on Smart Nutrition Pune Nutrition situation and Courtney Scott, The Food Foundation) stakeholder mapping 2018 Table of Contents About BINDI ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Nutrition Situational Analysis ............................................................................................................................. 3 Malnutrition in all its forms ............................................................................................................................ 3 Causes of malnutrition in Pune ..................................................................................................................... 6 Current Public Health / Food Interventions ................................................................................................... -

(Stapp) Skill Development and Employment

NISTADS Tracks in Policy Research: NISTADS/NTPR/STAPP/Skills/2019/1 CSIR–National Institute of Science, Technology and Development Studies S&T applicaTionS To peopleS’ problemS (STAPP) Skill Development and Employment P. Goswami Praveen Sharma 1 Page CSIR-NISTADS- STAPP/Drinking Water Project Information Project Team: Nodal Officer : Dr. P. Goswami Principal Investigator : Dr. Praveen Sharma Funding Agency: CSIR Publication Type: Interim Report Circulation: Limited Corresponding Author: P Goswami; [email protected] Acknowledgement: This Policy Advocacy benefitted from comments from a variety of sources, especially from CSIR laboratories. The analyses presented are based on mostly secondary sources (websites); while we have made sincere efforts to refer to all these sources, it is possible we have missed some. Finally, the critical comments on our earlier drafts from several reviewers are gratefully acknowledged. Disclaimer: The report is largely is descriptive in nature. It is based on secondary data and information composed from the related sources like reports, research papers and books. Also documents of various ministries/departments, organizations and information from many web-sites have been used. The internet data and information referenced in this report were correct, to the best of the knowledge, at the time of publication. Due to the dynamic nature of the internet, resources that are free and publicly available may subsequently require a fee or restrict access, and the location of items may change as menus and webpages are reorganized. 2 Page S &T applicaTionS To peopleS’ problemS (stapp): an ouTline The Prime Minister of India had on several occasions emphasized the need for addressing problems faced by the people of India, through S&T applications. -

Capacity Building

Kudumbashree Writeshop K B Sudheer, SMM (SM & ID) CAPACITY BUILDING What is Capacity Building? Capacity Building (CB) is a process by which individuals and organizations obtain, improve, and retain the skills, knowledge, tools, equipment and other resources needed to do their jobs competently or to a greater capacity (larger scale, larger audience, larger impact, etc). Capacity building is a conceptual approach to social, behavioural change and leads to infrastructure development. It simultaneously focuses on understanding the obstacles that inhibit people, governments, or any non-governmental organizations (NGOs), from realizing their development goals and enhancing the abilities that will allow them to achieve measurable and sustainable results. Human resources in any organizations are a key determinant of its success and are often the “face” of the organization to its stakeholders and collaborators. Maintaining a well-trained, well-qualified human resource is a critical function of the management. Kudumbashree also believes in capacity building of its staff for strengthening the skills, competencies and abilities of people and communities in the organisation so they can achieve their goals and potentially overcome the causes of their exclusion and suffering. Organizational capacity building is used by Kudumbashree to guide their organisational development and also personal growth of its personnel. Capacity Building helps in methods of CB. • Ensuring an organization’s clarity of mission – this involves evaluating an organization’s goals and how 1. Technology-based Learning well those goals are understood throughout the Common methods of learning via technology include: organization. • Basic PC-based programs • Developing an organization’s leadership – • Interactive multimedia - using a PC-based CD- this involves evaluating how empowered the ROM organization’s leadership is; how well the leadership • Interactive video - using a computer in conjunction encourages experimentation, self-reflection, with a VCR changes in team structures and approaches. -

Transforming India Through Make in India, Skill India and Digital India

through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & 1 through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & 2 through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & 3 through Make in India, Sk⬆⬆⬆ India & From President’s Desk We envisage a transformed India where the economy is in double digit growth trajectory, manufacturing sector is globally competitive, the agriculture sector is sufficient to sustain the rising population and millions of jobs are created for socio-economic development of the Dr. Mahesh Gupta nation. This transformation will take place through the dynamic policy environment announced by our esteemed Government. The policies like Make in India, Skill India and Digital India have the potential to “India has emerged as the boost not only economic growth but overall socio-economic development of the country to the next level. The inclusive one of the fastest moving development of the country would pave the way for peace, progress economies and a leading and prosperity. investment destination. The fact is that ever since India I believe, the economic activity is expected to regain its momentum in has launched dynamic the coming months with circulation of new currency in the system that reforms there has been no would lead to reduction in interest rates and higher aggregate demand. looking back. ” The theme of our 111th AGM is “Transforming India through Make in India, Skill India & Digital India’. The transformed India provide housing for all, education for all, easy access to medical and health facilities as well as safe and better standards of living to the population of India. Transformed India would promise every citizen to realize his or her potential and contribute towards self, family and the country.