Gone with the Wind and the Lost Cause Caitlin Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Scarlet O' Hara's Ambitions in Margaret Mitchell's Gone

Chapter 3 The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions and Her Ways to Obtain Them I begin the analysis by revealing the factors of O’Hara’s two ambitions, namely the willingness to rebuild Tara and the desire to win Wilkes’ love. I divide this chapter into two main subchapters. The first subchapter is about the factors of the two ambitions that Scarlett O’Hara has, whereas the second subchapter explains how she tries to accomplish those ambitions. 3.1. The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions The main female character in Gone with the Wind has two great ambitions; her desires to preserve the family plantation called Tara, and to win Ashley Wilkes’ love by supporting his family’s needs. Scarlett O’Hara herself confesses that “Every part of her, almost everything she had ever done, striven after, attained, belonged to Ashley, were done because she loved him. Ashley and Tara, she belonged to them” (Mitchell, 1936, p.826). I am convinced that there are many factors which stimulate O’Hara to get these two ambitions. Thus, I use the literary tools: the theories of characterization, conflict and setting to analyze the factors. 3.1.1. The Ambition to Preserve Tara Scarlett O’Hara’s ambition to preserve the family’s plantation is stimulated by many factors within her life. I divide the factors that incite Scarlett O’Hara’s ambitions into two parts, the factors found before the war and after. The factors before the war are the sense of belonging to her land, the Southern tradition, and Tara which becomes the source of income. -

"Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History Annjeanette C. Rose College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Annjeanette C., "Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625795. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g6vx-t170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING TO FORGET: GONE WITH THE WIND. ROOTS. AND CONSUMER HISTORY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Anjeanette C. Rose 1993 for C. 111 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CJ&52L- Author Approved, April 1993 L _ / v V T < Kirk Savage Ri^ert Susan Donaldson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. v ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................vi -

Experience Atlanta's True South

Experience Atlanta’s True South Clayton County, Georgia Official Home of Gone With the Wind Clayton County, Georgia is located just 15 miles south of Atlanta. Here, visitors will find the small town charm and southern hospitality that they expect. Whether its the convenience of being a few miles from the world’s busiest airport, the excitement of the Atlanta Motor Speedway, the lure of antebellum homes and museums, the history of Stately Oaks Plantation or the heritage at the State and National Archives - Clayton County, Georgia is Atlanta’s True South! What’s New and What’s News in Atlanta’s True South Official Home of Gone With the Wind Clayton County, Georgia is the Official Home of Gone With the Wind. On the first few pages of Margaret Mitchell’s world-renowned novel, Scarlett’s beloved home, Tara, is set in Jonesboro, Georgia. Clayton County is a part of the Gone With the Wind Trail, a state designated trail for visitors to follow, linking sites dedicated to Mar- garet Mitchell, her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel and the subsequent film. Featured sites include the Road to Tara Museum, Margaret Mitchell House, Atlanta Fulton County Public Library Oakland Cemetery and the Marietta Gone With the Wind Museum. Local Character Peter Bonner - Local historian and owner of Historical & Hysterical Tours, Peter brings life, laughter and fun into learning more about Gone With the Wind, the real people who inspired Mar- garet Mitchell’s famed characters and the pivotal Battle of Jonesboro. Birders’ Paradise The Newman Wetlands Center, a man-made 32-acre habitat and wetlands area, is home to waterfowl, raptors, song birds and more. -

Interpretation of Scarlett's Land Complex in Gone with the Wind

102 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN ENGINEERING AND SOCIETY, VOL.1, NO.4, Interpretation of Scarlett‘s Land Complex in Gone with the Wind from the Perspective of Humanity Shutao Zhou College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University, Daqing 163319, China [email protected] Abstract: The famous novel Gone with the Wind by Tara was leisurely and wealthy. In this context, a Margaret Mitchell takes the Civil War as the young girl who was just sixteen years old lived a background. With the three marriage experiences of carefree life without a single worry, and the only Scarlett as the main line, her strong feeling of land thing she thought of was how to attract the attention complex runs through the whole book. The red land of men. She did not realize the importance of land at at Tara witnessed Scarlett‘s gradual growth and all. maturity, revealing the eternal blood ties between When her father persuaded Scarlett to give up her land and Scarlett. This paper, by analyzing Scarlett‘s obsession with Ashley and give Tara to her, she life course, explores the development of the land would not mind or even be hostile to the idea of complex which is a process from unconsciousness to being the master of the land. As her father gave her fight for the land. Scarlett‘s land complex gave her a the generous gift, she said in fury, ―I wouldn‘t have vivid image. Cade on a silver tray,‖ ―And I wish you‘d quit Key words: Scarlett; Tara; Land Complex pushing him at me! I don‘t want Tara or any old plantation. -

Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett utleB r and the Law of War at Sea John Paul Jones University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation John Paul Jones, Into the Wind: Rhett uB tler and the Law of War at Sea, 31 J. Mar. L. & Com. 633 (2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, Vol. 31, No. 4, October, 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea JOHN PAUL JONES* I INTRODUCTION When Margaret Mitchell wrote Gone With the Wind, her epic novel of the American Civil War, she introduced to fiction the unforgettable character Rhett Butler. What makes Butler unforgettable for readers is his unsettling moral ambiguity, which Clark Gable brilliantly communicated from the screen in the movie version of Mitchell's work. Her clever choice of Butler's wartime calling aggravates the unease with which readers contemplate Butler, for the author made him a blockade runner. As hard as Butler is to figure out-a true scoundrel or simply a great pretender?-so is it hard to morally or historically pigeonhole the blockade running captains of the Confederacy. -

Gone with the Wind Part 1

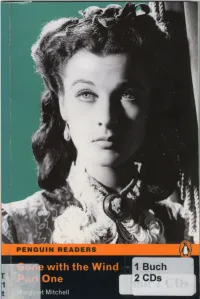

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ________________ No. 10-1743 ________________ Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros. Consumer Products, * Inc.; Turner Entertainment Co., * * Appellees, * * v. * Appeal from the United States * District Court for the X One X Productions, doing * Eastern District of Missouri. business as X One X Movie * Archives, Inc.; A.V.E.L.A., Inc., * doing business as Art & Vintage * Entertainment Licensing Agency; * Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc.; Leo * Valencia, * * Appellants. * _______________ Submitted: February 24, 2011 Filed: July 5, 2011 ________________ Before GRUENDER, BENTON, and SHEPHERD, Circuit Judges. ________________ GRUENDER, Circuit Judge. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., X One X Productions, and Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc. (collectively, “AVELA”) appeal a permanent injunction prohibiting them from licensing certain images extracted from publicity materials for the films Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, as well as several animated short films featuring the cat- and-mouse duo “Tom & Jerry.” The district court issued the permanent injunction after granting summary judgment in favor of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc., Warner Bros. Consumer Products, Inc., and Turner Entertainment Co. (collectively, “Warner Bros.”) on their claim that the extracted images infringe copyrights for the films. For the reasons discussed below, we affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand for appropriate modification of the permanent injunction. I. BACKGROUND Warner Bros. asserts ownership of registered copyrights to the 1939 Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM”) films The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Before the films were completed and copyrighted, publicity materials featuring images of the actors in costume posed on the film sets were distributed to theaters and published in newspapers and magazines. -

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell Collection, 1922-1991

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Mitchell, Margaret. Title: Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 265 Extent: 3.75 linear feet (8 boxes), 1 oversized papers box and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), and AV Masters: .5 linear feet (1 box, 1 film, 1 CLP) Abstract: Papers of Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell including correspondence, photographs, audio-visual materials, printed material, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: Requests to publish original Mitchell material should be directed to: GWTW Literary Rights, Two Piedmont Center, Suite 315, 3565 Piedmont Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30305. Related Materials in Other Repositories Margeret Mitchell family papers, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia and Margaret Mitchell collection, Special Collections Department, Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library. Source Various sources. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Manuscript Collection No. -

Happy 75Th Anniversary

Literature County girlhood home, Tara. Clayton County was designated the official home of Gone with the Wind by Mitchell’s brother Stephens. All around were signs that this is truly GWTW country: Tara Elementary School, Tara Wedding Chapel, Tara Gone with the Wind Florist and – well, you get the idea. The county has even had a couple of Scarletts: Melly Meadows, a striking Vivien Leigh lookalike who traveled worldwide in this role, delighting Happy 75th Anniversary everyone she meets with her fiddle-dee-dees and, more recently, By Lillian Africano Cynthia Evans. My GWTW orientation began at the Road to Tara Museum, housed in the 1867 Jonesboro Railroad Station, Gone with the Wind about 15 miles south of Atlanta. Movie Set This relatively small museum has BELOW Gone with the Wind drawn Windies from all over the Movie Poster world; the guest book includes visitors from Norway, Finland, Sweden, New Zealand, Australia, largest collections of GWTW At the Patrick Cleburne Memorial the U.K., China and Japan. autographed photos. Olivia de Confederate Cemetery, where some Haviland, who played Melly and who 1,000 fallen soldiers from the Battle Here is so much to delight the most celebrated her 98th birthday in July, of Jonesboro are buried, Bonner, who dedicated fan: first editions of the is here of course, but so are the has taken part in past re-enactments novel, autographed photos, costumes movie’s bit players, such as the of the battle, vividly described the (including the pantalets worn by Tarleton twins. (Actor George ferocity of the two-day combat. -

Why Atlanta for the Permanent Things?

Atlanta and The Permanent Things William F. Campbell, Secretary, The Philadelphia Society Part One: Gone With the Wind The Regional Meetings of The Philadelphia Society are linked to particular places. The themes of the meeting are part of the significance of the location in which we are meeting. The purpose of these notes is to make our members and guests aware of the surroundings of the meeting. This year we are blessed with the city of Atlanta, the state of Georgia, and in particular The Georgian Terrace Hotel. Our hotel is filled with significant history. An overall history of the hotel is found online: http://www.thegeorgianterrace.com/explore-hotel/ Margaret Mitchell’s first presentation of the draft of her book was given to a publisher in the Georgian Terrace in 1935. Margaret Mitchell’s house and library is close to the hotel. It is about a half-mile walk (20 minutes) from the hotel. http://www.margaretmitchellhouse.com/ A good PBS show on “American Masters” provides an interesting view of Margaret Mitchell, “American Rebel”; it can be found on your Roku or other streaming devices: http://www.wgbh.org/programs/American-Masters-56/episodes/Margaret-Mitchell- American-Rebel-36037 The most important day in hotel history was the premiere showing of Gone with the Wind in 1939. Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, and Olivia de Haviland stayed in the hotel. Although Vivien Leigh and her lover, Lawrence Olivier, stayed elsewhere they joined the rest for the pre-Premiere party at the hotel. Our meeting will be deliberating whether the Permanent Things—Truth, Beauty, and Virtue—are in fact, permanent, or have they gone with the wind? In the movie version of Gone with the Wind, the opening title card read: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South.. -

An Incredible Investment Opportunity the Twelve Oaks in a Truly

An Incredible Investment Opportunity The Twelve Oaks in a truly exceptional business opportunity. It is already income-producing, profitable, and award-winning. There are four different avenues for producing revenue with all permits already in place: as a Bed & Breakfast, an event venue, a historic site offering tours, and as a location for filming located right in the heart of the original “Hollywood of the South” in Covington, GA, which is an area for tremendous growth and part of the metro Atlanta area. The world’s busiest international airport is just 38 miles from the property and Covington houses its own regional airport as well. Georgia welcomes over 100 million tourists per year1 and approximately 50 million visit the Atlanta area. Income Opportunities: 1. Bed & Breakfast/Luxury Inn: The property opened as a Bed & Breakfast for the first time in late 2012. Every year since opening has brought tremendous growth and unheard of awards for a “new” inn. Some of the awards won and recognitions received follow: • Southern Living South’s Best Inns: Just last year (2018), the readers of Southern Living voted the Twelve Oaks as one of the South’s Best Inns in the #4 spot! This is amazing as a relatively “new” inn opened just six years prior beat out places like The Cloister, Blackberry Farm, Grove Park Inn, etc. • Tripadvisor Hall of Fame (2019 and 2018). Every year Tripadvisor gives a Certificate of Excellence to places with amazing reviews. The Twelve Oaks has received a Certificate of Excellence for every single year in business and was thus inducted into the “Hall of Fame” in 2018 and just received the designation for 2019 as well. -

The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara Into a Plantation Parody

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 52 Issue 4 Article 16 2002 The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara into a Plantation Parody Jeffrey D. Grossett Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey D. Grossett, The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara into a Plantation Parody, 52 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1113 (2002) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol52/iss4/16 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE WIND DONE GONE: TRANSFORMING TARA INTO A PLANTATION PARODY In June 2001, amid a flurry of legal wrangling, Houghton Mifflin Company sent to print Alice Randall's first novel, The Wind Done Gone.' Described by the publisher as a "provocative literary parody that explodes the mythology perpetrated by a Southern Classic,"'2 the novel takes direct aim at Margaret Mitchell's Gone with the Wind,3 the definitive epic novel of the Civil War era South.4 Targeting the racist and paternalistic treatment of African-American slaves perva- sive throughout Gone with the Wind,5 Randall's novel begins by re- telling the Gone with the Wind story from the perspective of an ille- gitimate mulatto slave, Cynara.6 It then proceeds to the tales that Gone with the Wind left untold-the events of Scarlett's anxiously awaited "tomorrow," and the sad conclusion to Scarlett7 and Rhett's tempestuous relationship, as seen through Cynara's eyes.