Business Ethos and Gender in Margaret Mitchell's Gone with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History Annjeanette C. Rose College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Annjeanette C., "Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625795. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g6vx-t170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING TO FORGET: GONE WITH THE WIND. ROOTS. AND CONSUMER HISTORY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Anjeanette C. Rose 1993 for C. 111 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CJ&52L- Author Approved, April 1993 L _ / v V T < Kirk Savage Ri^ert Susan Donaldson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. v ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................vi -

Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett utleB r and the Law of War at Sea John Paul Jones University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation John Paul Jones, Into the Wind: Rhett uB tler and the Law of War at Sea, 31 J. Mar. L. & Com. 633 (2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, Vol. 31, No. 4, October, 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea JOHN PAUL JONES* I INTRODUCTION When Margaret Mitchell wrote Gone With the Wind, her epic novel of the American Civil War, she introduced to fiction the unforgettable character Rhett Butler. What makes Butler unforgettable for readers is his unsettling moral ambiguity, which Clark Gable brilliantly communicated from the screen in the movie version of Mitchell's work. Her clever choice of Butler's wartime calling aggravates the unease with which readers contemplate Butler, for the author made him a blockade runner. As hard as Butler is to figure out-a true scoundrel or simply a great pretender?-so is it hard to morally or historically pigeonhole the blockade running captains of the Confederacy. -

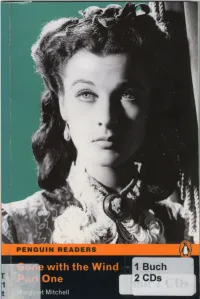

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ________________ No. 10-1743 ________________ Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros. Consumer Products, * Inc.; Turner Entertainment Co., * * Appellees, * * v. * Appeal from the United States * District Court for the X One X Productions, doing * Eastern District of Missouri. business as X One X Movie * Archives, Inc.; A.V.E.L.A., Inc., * doing business as Art & Vintage * Entertainment Licensing Agency; * Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc.; Leo * Valencia, * * Appellants. * _______________ Submitted: February 24, 2011 Filed: July 5, 2011 ________________ Before GRUENDER, BENTON, and SHEPHERD, Circuit Judges. ________________ GRUENDER, Circuit Judge. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., X One X Productions, and Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc. (collectively, “AVELA”) appeal a permanent injunction prohibiting them from licensing certain images extracted from publicity materials for the films Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, as well as several animated short films featuring the cat- and-mouse duo “Tom & Jerry.” The district court issued the permanent injunction after granting summary judgment in favor of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc., Warner Bros. Consumer Products, Inc., and Turner Entertainment Co. (collectively, “Warner Bros.”) on their claim that the extracted images infringe copyrights for the films. For the reasons discussed below, we affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand for appropriate modification of the permanent injunction. I. BACKGROUND Warner Bros. asserts ownership of registered copyrights to the 1939 Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM”) films The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Before the films were completed and copyrighted, publicity materials featuring images of the actors in costume posed on the film sets were distributed to theaters and published in newspapers and magazines. -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Open Tiffany Wesner Thesis Final

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DIVISION OF HUMANITIES, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES GONE WITH THE WIND AND ITS ENDURING APPEAL TIFFANY WESNER SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Baccalaureate Degree in American Studies with honors in American Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Raymond Allan Mazurek Associate Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Sandy Feinstein Associate Professor of English Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The white antebellum woman has occupied an evolving archetypal status in American culture throughout the twentieth century. In 1936, Margaret Mitchell published Gone with the Wind and extended the tradition of featuring Southern belles in novels. However, Mitchell chose to alter stereotypical depictions of her heroine and incorporate a theme of survival. Her main character, Scarlett O'Hara, was a prototypical Southern woman of her day. Scarlett was expected to conform to rigidly defined social boundaries but, through acts of defiance and independence, she forged new paths for herself and her family along her route to survival. This thesis investigates the 1939 film adaptation of Mitchell's novel and the contributions of David O. Selznick, Vivien Leigh, and Hattie McDaniel to the story that chronicled Scarlett's transformation from stereotypical Southern belle to independent survivor. This analysis demonstrates that Scarlett depicted the new Southern Woman whose rising to define a diversity of roles embodied the characteristics of the New Woman. The film’s feminist message, romantic grandeur, ground-breaking performances, themes of survival through times of crisis, and opulent feminine appeal all combined in Gone With the Wind to create an American classic with enduring appeal. -

Gone with the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy

Gone With the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy (Tara is the beautiful homeland of Scarlett, who is now talking with the twins, Brent and Stew, at the door step.) BRENT What do we care if we were expelled from college, Scarlett. The war is going to start any day now so we would have left college anyhow. STEW Oh, isn't it exciting, Scarlett? You know those poor Yankees actually want a war? BRENT We'll show 'em. SCARLETT Fiddle-dee-dee. War, war, war. This war talk is spoiling all the fun at every party this spring. I get so bored I could scream. Besides, there isn't going to be any war. BRENT Not going to be any war? STEW Ah, buddy, of course there's going to be a war. SCARLETT If either of you boys says "war" just once again, I'll go in the house and slam the door. BRENT But Scarlett honey.. STEW Don't you want us to have a war? BRENT Wait a minute, Scarlett... STEW We'll talk about this... BRENT No please, we'll do anything you say... SCARLETT Well- but remember I warned you. BRENT I've got an idea. We'll talk about the barbecue the Wilkes are giving over at Twelve Oaks tomorrow. STEW That's a good idea. You're eating barbecue with us, aren't you, Scarlett? SCARLETT Well, I hadn't thought about that yet, I'll...I'll think about that tomorrow. STEW And we want all your waltzes, there's first Brent, then me, then Brent, then me again, then Saul. -

Gone with the Wind and the Lost Cause Caitlin Hall

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2019 Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause Caitlin Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Caitlin, "Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause" (2019). University Honors Program Theses. 407. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/407 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gone with the Wind and the Myth of the Lost Cause An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature. By Caitlin M. Hall Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind is usually considered a sympathetic portrayal of the suffering and deprivation endured by Southerners during the Civil War. I argue the opposite, that Mitchell is subverting the Southern Myth of the Lost Cause, exposing it as hollow and ultimately self-defeating. Thesis Mentor:________________________ Dr. Joe Pellegrino Honors Director:_______________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2019 Department Name University Honors Program Georgia Southern University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements -

Cottonwood Estates

255 Vaughan Drive • Alpharetta, GA 30009 • Phone (678) 242-0334 • www.seniorlivinginstyle.com JUNE 2021 Men’s Breakfast Group Outing COTTONWOOD ESTATES STAFF On June 16th, our Men’s Breakfast Managers ............. CHRIS & SALLY BLANCHARD Group that meets Executive Chef ........................ JONATHAN ELAM once a month for Marketing ..................................SEÃN JOHNSON coffee and breakfast Activity Coordinator .................... JOHN CARSON is finally going out Maintenance ������������������������������� MARK SIMMS for a field trip and Transportation ......................... THOMAS BABER breakfast. It has been a long-time coming. After spending lots of time reviewing and TRANSPORTATION researching several Monday, 9:30 a.m.: Windward Pkwy. Shopping places to go for the Monday, 2 p.m.: Windward Pkwy. Shopping outing, a decision was made. Drum roll, please! John, the Tuesday, 9 a.m.-2 p.m.: Doctor Appointments Activity Coordinator, decided to take our Men’s Breakfast Wednesday, 10:30 a.m.: Outing Group for hearty breakfast at the Red Eyed Mule, which Thursday, 9 a.m.-2 p.m.: Doctor Appointments is a local favorite of the residents of Kennesaw, Georgia. Friday, 9:30 a.m. .: Northpoint Pkwy. Shopping After breakfast, the men will be treated to visiting The Friday, 2 p.m.: Northpoint Pkwy. Shopping Southern Museum of the Civil War and Locomotive History in old town Kennesaw, Georgia. The men will have the opportunity to look over a significant collection of company records, engineering drawings, blueprints, glass plate negatives, photographs and correspondence from various American businesses representing the railroad industry in the South after the Civil War. Also, they can look over a major collection of Civil War letters, diaries, and official records from that time period. -

Gone with the Wind – Part Two Book Key D Some Negro Men Are Rude and Insulting to White 1 a Blockader, Convict, Confederate, Mammy, Negro, Pa, People

LEVEL 4 Answer keys Teacher Support Programme Gone With The Wind – Part Two Book key d Some negro men are rude and insulting to white 1 a blockader, convict, confederate, Mammy, negro, Pa, people. prostitute, slave, trash, Yankee e Rhett Butler is in prison for killing a negro. He has b carriage, wagon stolen some confederate money. c cheek, nail 7 She visits Rhett in prison, telling him everything is fine 2 a Scarlett has lost her husband and friends in the civil in Tara. Everything is not fine in Tara and she actually war. She has to pay high taxes to Northerners. She wants Rhett’s money. is clever, strong and independent. Scarlett wants 8–9 open answers Ashley, but he does not love her. Rhett is handsome, 10 a F dangerous, wealthy and rich. Melanie is a loyal friend b T to Scarlett. c T b Before the war, negro slaves had been made to d T work hard for rich white plantation owners. At e F the end of the civil war, negro slaves were freed. 11 a hang However, many negroes did not know how to live b dishonest as free men so they continued to work as before. c Suellen Negroes were often threatened by the Ku Klux Klan. d Yankees c Carpetbaggers were men who came from the e sign North. They came south to demand money from 12 a Scarlett marries him because he has wealth and can southerners or buy their land cheaply. provide opportunities to make more money. d The northern Yankees beat the southerners in the b Scarlett didn’t realise that Rhett was very wealthy civil war. -

Gone with the Wind Is Di Smissed by Many Critics As a Racist Film, and Therefore, Unworthy of Discussion

A N I L L U M I N E D I L L U S I O N S E S S A Y B Y I A N C . B L O O M GG OO NN EE WW II TT HH TT HH EE WW II NN DD Directed by Victor Fleming Produced by David O. Selznick Distributed by Metro - Goldwyn - Mayer Released in 1939 ead a different dictionary, get a different definition of racism. Variously, it could be (and R is) defined as a p rejudice of dislike/disdain/distrust against a person of a particular race, because of his race and not the person, himself. Or it is reckoned to be manifested in one person's dislike/disdain/distrust of another person even though the object - person's race is not a contributing factor to the supposed - bigot's view. Alternatively, it could be discerned in the words of a person who is making a sweeping statement attributing to a race of people a defining or frequently - observed characteristic (even if positive ). Or, an accusation of racism need not, perhaps, be justified at all; it is merely the 'gotcha' word that wins an argument by default. For if the speaker is successfully maligned, his argument will be dismissed out of hand. Gone With The Wind is di smissed by many critics as a racist film, and therefore, unworthy of discussion. Given that neither blacks, slavery, nor emancipation are a central focus of the film, it is difficult to describe the entire production as racist. However, the film may very well betray racist tendencies in how it handles — or ignores — black characters. -

Two Chiefs a Roseville Crime Report Pg 49 Sun City Roseville's New Landscape Department Pg 29

Vol. 22 / Edition III March 2016 2016 Bird of the Month FINCHES Show pg 18 & Sale Artpg 46 Two Chiefs a roseville crime report pg 49 sun city roseville's new Landscape Department pg 29 pg 32 Sun City Roseville • www.scres.org Sun City Roseville IN THIS ISSUE… 2015-2016 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Activities 57 President: Don Treichler 791-0777 [email protected] Vice President: Tim Hinchey 788-8423 [email protected] Activities Update 7 Secretary: Mary Ann Chittick 773-3259 [email protected] Advertiser Directory 24 Treasurer: Herb Drosdat 781-9988 [email protected] Ambassador Committee 14 Director: Dan Arriola 772-3794 [email protected] Architectural Review Committee 14 Director: Linda Breninger 771-5685 [email protected] Art Show and Sale 46 Director: Dave Lewis 907-748-4000 [email protected] Bird of the Month - Finches 18 Board of Directors 3 ASSOCIATION CONTACTS Calendars insert Timber Creek Lodge 7050 Del Webb Blvd, Roseville CA 95747 Citizens Patrol/Neighborhood Watch 21 Administration Office Club Updates 37 General Information 774-3880 Compliance Committee 15 Cover Story - Gone with the Wind 32 Earl Wiklund, Executive Director 774-3862 [email protected] Executive Director 4 Accounting 774-3865 [email protected] Fine Arts Gallery 35 James P. Martin, Controller Fitness Center News 12 Activities 774-3877 [email protected] Food & Beverage News 7 & 50 Sharon Mowry, Activities Director Foundation 26 Activities Monitor Desk 774-3888 Golf Pro 11 Catering 774-3870 [email protected] Group Updates 51 Jenny Giallanza, Sales