Open Tiffany Wesner Thesis Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parking Who Was J 60P NAMES WARREN Gary Cooper

Metro, is still working on the same tator state that she was going to thing cute.” He takes me into the day,* had to dye her brown hair is his six- contract she signed when she was marry Lew Ayres when she gets her television room, and there yellow. Because, Director George wife. Seems to year-old daughter Jerilyn dining Mickey Rooney’s freedom from Ronald Reagan. She Seaton reasoned, "They wouldn't me she rates something new in alone, while at the same time she Hollywood: that’s because have a brunette daughter.” the way of remuneration. says quite interesting, watches a grueling boxing match on Back in Film is from Business, Draft May Take Nancy Guild, now recovered from she hasn’t yet had a date with Lew. the radio. Charles Grapewin retiring Hughes, making pictures when he finishes her session with Orson Welles in John Garfield is doing a Bing Gregory Peck gets Robyt Siod- Kay Thompson’s into two his present film, "Sand,” after 52 “Cagliostro,” goes pictures for his Franchot Tone. mak to direct him in "Great Sinner.” Minus Brilliance of Crosby pal, years in the business. And they Schary Williams Bros. —the Clifton Webb “Belvedere Goes That's a break for them both. He in a bit role in Fran- used to the movies were a By Jay Carmody to College,” and “Bastille” for Wal- appears Celeste Holm and Dan Dailey are say pre- carious ferocious whose last Hollywood Sheilah Graham ter Wanger. chot's picture, “Jigsaw.” both so their Coleen profession! Howard Hughes, the independent By blond, daughter North American Richard under (Released by sensation was production of the stupid, bad-taste "The Outlaw," has Burt Lancaster, thwarted in his Conte, suspension Nina Foch is the only star to beat Townsend, in "Chicken Every Sun- Newspaper Alliance.) at 20thtFox for refusing to work in come up with another that has the movie capital talking. -

Great Literature Collection

Great Literature Collection Aldrich Ames: Traitor Within CIA operative Aldrich Ames has, like his father, always been a company man. Although not always competent, he is chief of the Counter Intelligence Soviet Branch and has few friends within the Agency. On the verge of financial ruin due to, among other things, his wife Rosario's heavy spending, the hard-drinking and desperate Ames decides to sell secrets to the Russians. His first "job" has fatal consequences for ten Russians who worked for the CIA. Ames' boss, the Chief of Operations, who is friendly toward Ames, discovers that someone within the CIA is divulging high-level information. He appoints Jeanne Vertefeuille to head up the investigation. Jeanne recruits her own older staff, derisively dubbed the "over the hill gang". Poring through an abundance of records, case files and information proves to be an awesome task and their search goes on for eight years. After a year-long stint in Rome and now with Bush in the White House, Ames continues turning over information to the Russians for millions of dollars, re-routing deposits to Swiss banks and his wife's family in Colombia. Still an alcoholic, he buys a Jaguar and moves his family to an expensive home in a plush suburb. Ames soon realizes, however, that the investigation is closing in and gets very nervous when a Russian politico who could disclose Ames' duplicity defects to America. Ames gets lucky, his treason is not yet uncovered. Ames' own actions, however, begin to draw suspicion towards him, especially when he tries to conduct his own investigation to uncover the spy within the CIA. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

British Film Journalism

Good of its kind? British film journalism HALL, Sheldon <http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0950-7310> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/12366/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version HALL, Sheldon (2017). Good of its kind? British film journalism. In: HUNTER, Ian Q., PORTER, Laraine and SMITH, Justin, (eds.) The Routledge History of British Cinema. London, Routledge, 271-281. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk GOOD OF ITS KIND? BRITISH FILM JOURNALISM Sheldon Hall In his introduction to the 1986 collection All Our Yesterdays: 90 Years of British Cinema, Charles Barr noted that successive phases in the history of minority film culture in the UK have been signposted by the appearance of a series of small-circulation journals, each of which in turn represented “the ‘leading edge’ or growth point of film criticism in Britain” (5). These journals were, in order of their appearance: Close-Up, first published in 1927; Cinema Quarterly (1932) and its direct successors World Film News (1936) and Documentary News Letter (1940), all linked to the documentary movement; Sequence (1947); Sight and Sound (1949, the date when the longstanding BFI house journal’s editorship was assumed by Sequence alumnus Gavin Lambert); Movie (1962); and Screen (1971, again the date of a change in editorial direction rather than a first issue as such). -

213 Nothing Like the South: Aurora Greenway – a Belle

NOTHING LIKE THE SOUTH: AURORA GREENWAY – A BELLE IN EXILE Anca Peiu University of Bucharest Larry McMurtry’s Terms of Endearment has been better known as a 1983 successful silver-screen story than as a 1975 best-selling novel, rather as a multiplereceiver of Academy Awards than as a most accomplished book by a prolific author and Pulitzer Prize winner. My return to it is justified by some recently read essays – neither on the film, nor on the book – but on the Belle and the South (indeed, an archetypal coupling somehow echoing Beauty and the Beast ). As for my title here – it oscillates between two Shakesperean sonnets: Sonnet 130 and Sonnet 3. Both poems appeal particularly to the sense of sight ; they are versions of that type of painting (also fiction) known as a portrait of a lady – who stays the lady even if she defies any canon of lady-likelihood – both as Shakespeare’s (image of the) lover and as McMurtry’s Southern Belle – from My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun… Thou art thy mother’s glass, and she in thee Calls back the lovely April of her prime; So thou through windows of thine age shalt see, Despight of wrinkles, this thy golden time… The latter quote opens Larry McMurtry’s novel, as a necessary motto. It evokes a specific traditional relationship: mother-daughter, by the classic symbol of the mirror . It could send us – via Larry McMurtry’s novel – to Katherine Henninger’s astute study of the impact of photography on the Visual Legacies of the South: Picture a southern woman . -

Chapters 1-10 Notes

Notes and Sources Chapter 1 1. Carol Steinbeck - see Dramatis Personae. 2. Little Bit of Sweden on Sunset Boulevard - the restaurant where Gwyn and John went on their first date. 3. Black Marigolds - a thousand year’s old love poem (in translation) written by Kasmiri poet Bilhana Kavi. 4. Robert Louis Stevenson - Scottish novelist, most famous for Treasure Island, Kidnapped and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Stevenson met with one of the Wagner family on his travels. He died aged 44 in Samoa. 5. Synge – probably the Irish poet and playwright. 6. Matt Dennis - band leader, pianist and musical arranger, who wrote the music for Let’s Get Away From It All, recorded by Frank Sinatra, and others. 7. Dr Paul de Kruif - an American micro-biologist and author who helped American writer Sinclair Lewis with the novel Arrowsmith, which won a Pulitzer Prize. 8. Ed Ricketts - see Dramatis Personae. 9. The San Francisco State Fair - this was the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939 and 1940, held to celebrate the city’s two newly built bridges – The San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge and The Golden Gate Bridge. It ran from February to October 1939, and part of 1940. At the State Fair, early experiments were being made with television and radio; Steinbeck heard Gwyn singing on the radio and called her, some months after their initial meeting. Chapter 2 1. Forgotten Village - a screenplay written by John Steinbeck and released in 1941. Narrated by Burgess Meredith - see Dramatis Personae. The New York authorities banned it, due to the portrayal of childbirth and breast feeding. -

"Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History Annjeanette C. Rose College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Annjeanette C., "Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625795. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g6vx-t170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING TO FORGET: GONE WITH THE WIND. ROOTS. AND CONSUMER HISTORY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Anjeanette C. Rose 1993 for C. 111 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CJ&52L- Author Approved, April 1993 L _ / v V T < Kirk Savage Ri^ert Susan Donaldson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. v ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................vi -

Unconquered Pdf, Epub, Ebook

UNCONQUERED PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Shirley | 374 pages | 01 Oct 2012 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781439198483 | English | New York, United States Unconquered PDF Book Log in with Facebook. DeMille was forced to use a stuntwoman, who got burned. Boris Karloff Guyasuta. Charles Bennett Fredric M. Parents Guide. Afterward, Holden kills Garth in a shootout, leaving him and Abby free to marry, ending her slavery. However, when Holden and his two companions are ambushed, he realizes that he needs to deal with Garth. Please enter your email address and we will email you a new password. You're almost there! External Reviews. After setting Abby free on shore, Holden learns that Native Americans are plotting to attack the settlers. Full Cast and Crew. Orphan Black: Season 5. American Ninja Warrior. He takes Abby along. Add Article. Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? See score details. Hutchins Oliver Thorndike as Lieut. When the unconquered , unconquerable spirit of mankind is allowed to soar to its full potential we will achieve a world in which truth and justice prevail, a world which we can proudly bequeath to the unborn generations of our peoples. Feb 17, For all its absurdity Unconquered has its Technicolorful moments Unconquered is a miracle of bad filmmaking. DeMille overindulging himself for two and a half hours, offering us a healthy heaping of camp, costumes, sexual titillation, and over the top action. According to Komatina, they lived in the valleys of present-day Morava river basin in Serbia, and were still unconquered by the Bulgarians. By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and Fandango. -

Selznick Memos Concerning Gone with the Wind-A Selection

Selznick memos concerning Gone with the Wind-a selection Memo from David O. Se/znick, selected and edited by Rudy Behlmer (New York: Viking, 1972) 144 :: MEMO FROM DAVID O. SELZNICK Gone With the Wind :: 145 To: Mr. Wm. Wright January 5, 1937 atmosphere, or because of the splendid performances, or because of cc: Mr. M. C. Cooper George's masterful job of direction; but also because such cuts as we . Even more extensive than the second-unit work on Zenda is the made in individual scenes defied discernment. work on Gone With the Wind, which requires a man really capable, We have an even greater problem in Gone With the Wind, because literate, and with a respect for research to re-create, in combination it is so fresh in people's minds. In the case of ninety-nine people out with Cukor, the evacuation of Atlanta and other episodes of the war of a hundred who read and saw Copperfield, there were many years and Reconstruction Period. I have even thought about [silent-fllm between the reading and the seeing. In the case of Gone With the director1 D. W. Griffith for this job. Wind there will be only a matter of months, and people seem to be simply passionate about the details of the book. All ofthis is a prologue to saying that I urge you very strongly indeed Mr. Sidney Howard January 6, 1937 against making minor changes, a few of which you have indicated in 157 East 8znd Street your adaptation, and which I will note fully. -

Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett utleB r and the Law of War at Sea John Paul Jones University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation John Paul Jones, Into the Wind: Rhett uB tler and the Law of War at Sea, 31 J. Mar. L. & Com. 633 (2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, Vol. 31, No. 4, October, 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea JOHN PAUL JONES* I INTRODUCTION When Margaret Mitchell wrote Gone With the Wind, her epic novel of the American Civil War, she introduced to fiction the unforgettable character Rhett Butler. What makes Butler unforgettable for readers is his unsettling moral ambiguity, which Clark Gable brilliantly communicated from the screen in the movie version of Mitchell's work. Her clever choice of Butler's wartime calling aggravates the unease with which readers contemplate Butler, for the author made him a blockade runner. As hard as Butler is to figure out-a true scoundrel or simply a great pretender?-so is it hard to morally or historically pigeonhole the blockade running captains of the Confederacy. -

Uncut! First Time In

45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:38 AM Page 1 THE AMERICAN FILM INSTITUTE GUIDE April 23 - June 13, 2004 ★ TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS VOLUME 1 • ISSUE 10 AFIPREVIEW UNCUT! FIRST TIME IN DC! GODZILLA!GODZILLA! Plus: Great World War II Films, Filmfest DC, Val Lewton Centennial, Three by Alfred Hitchcock, Natalie Wood Tribute MC5*A TRUE TESTIMONIAL POINT OF ORDER A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE CITY LIGHTS GODSEND SYLVIA BLOWUP DARK VICTORY SEPARATE BUT EQUAL STORMY WEATHER CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF WAR AND PEACE PHOTO NEEDED WORD WARS 45833_AFI_AGS 3/30/04 11:39 AM Page 2 Features 2, 3, 4, 7, 13 2 POINT OF ORDER MEMBERS ONLY SPECIAL EVENT! 3 MC5 *A TRUE TESTIMONIAL, GODZILLA GODSEND MEMBERS ONLY 4WORD WARS, CITY LIGHTS ●M ADVANCE SCREENING! 7 KIRIKOU AND THE SORCERESS Wednesday, April 28, 7:30 13 WAR AND PEACE, BLOWUP When an only child, Adam (Cameron Bright), is tragically killed 13 Two by Tennessee Williams—CAT ON A HOT on his eighth birthday, bereaved parents Rebecca Romijn-Stamos TIN ROOF and A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE and Greg Kinnear are befriended by Robert De Niro—one of Romijn-Stamos’s former teachers and a doctor on the forefront of Filmfest DC 4 genetic research. He offers a unique solution: reverse the laws of nature by cloning their son. The desperate couple agrees to the The Greatest Generation 6-7 experiment, and, for a while, all goes well under 6Featured Showcase—America Celebrates the the doctor’s watchful eye. Greatest Generation, including THE BRIDGE ON The “new” Adam grows THE RIVER KWAI, CASABLANCA, and SAVING into a healthy and happy PRIVATE RYAN young boy—until his Film Series 5, 11, 12, 14 eighth birthday, when things start to go horri- 5 Three by Alfred Hitchcock: NORTH BY bly wrong. -

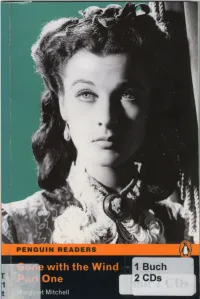

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said.