Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History Annjeanette C. Rose College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Annjeanette C., "Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625795. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g6vx-t170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING TO FORGET: GONE WITH THE WIND. ROOTS. AND CONSUMER HISTORY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Anjeanette C. Rose 1993 for C. 111 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CJ&52L- Author Approved, April 1993 L _ / v V T < Kirk Savage Ri^ert Susan Donaldson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. v ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................vi -

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE The Maltese Falcon introduced a new detective – Sam Spade – whose physical aspects (shades of his conversation with Stein) now approximated Hammett’s. The novel also originated a fresh narrative direction. The Op related his own stories and investigations, lodging his idiosyncrasies, omissions and intuitions at the core of Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. For The Maltese Falcon Hammett shifted to a neutral, but chilling third-person narration that consistently monitors Spade from the outside – often insouciantly as a ‘blond satan’ or a smiling ‘wolfish’ cur – but never ventures anywhere Spade does not go or witnesses anything Spade doesn’t see. This cold-eyed yet restricted angle prolongs the suspense; when Spade learns of Archer’s murder we hear only his end of the phone call – ‘Hello . Yes, speaking . Dead? . Yes . Fifteen minutes. Thanks.’ The name of the deceased stays concealed with the detective until he enters the crime scene and views his partner’s corpse. Never disclosing what Spade is feeling and thinking, Hammett positions indeterminacy as an implicit moral stance. By screening the reader from his gumshoe’s inner life, he pulls us into Spade’s ambiguous world. As Spade consoles Brigid O’Shaughnessy, ‘It’s not always easy to know what to do.’ The worldly cynicism (Brigid and Spade ‘maybe’ love each other, Spade says), the coruscating images of compulsive materialism (Spade no less than the iconic Falcon), the strings of point-blank maxims (Spade’s elegant ‘I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble’): Sam Spade was Dashiell Hammett’s most appealing and enduring creation, even before Bogart indelibly limned him for the 1941 film. -

Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett utleB r and the Law of War at Sea John Paul Jones University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation John Paul Jones, Into the Wind: Rhett uB tler and the Law of War at Sea, 31 J. Mar. L. & Com. 633 (2000) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. journal of Maritime Law and Commerce, Vol. 31, No. 4, October, 2000 Into the Wind: Rhett Butler and the Law of War at Sea JOHN PAUL JONES* I INTRODUCTION When Margaret Mitchell wrote Gone With the Wind, her epic novel of the American Civil War, she introduced to fiction the unforgettable character Rhett Butler. What makes Butler unforgettable for readers is his unsettling moral ambiguity, which Clark Gable brilliantly communicated from the screen in the movie version of Mitchell's work. Her clever choice of Butler's wartime calling aggravates the unease with which readers contemplate Butler, for the author made him a blockade runner. As hard as Butler is to figure out-a true scoundrel or simply a great pretender?-so is it hard to morally or historically pigeonhole the blockade running captains of the Confederacy. -

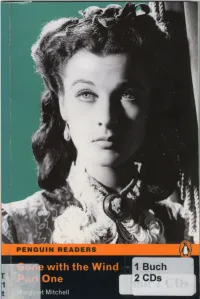

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Politics and the 1920S Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77

Politics and the 1920s Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77 Politics and the 1920s Writings of Dashiell Hammett J. A. Zumoff At first glance, Dashiell Hammett appears a common figure in American letters. He is celebrated as a left-wing writer sympathetic to the American Communist Party (CP) in the 1930s amid the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe. Memories of Hammett are often associated with labor and social struggles in the U.S. and Communist “front groups” in the post-war period. During the period of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communism, Hammett, notably, refused to collaborate with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s (HUAC) investigations and was briefly jailed and hounded by the government until his death in 1961. Histories of the “literary left” in the twentieth century, however, ignore Hammett.1 At first glance this seems strange, given both Hammett’s literary fame and his politics. More accurately, this points to the difficulty of turning Hammett into a member of the “literary left” based on his literary work, as opposed to his later political activity. At the same time, some writers have attempted to place Hammett’s writing within the context of the 1930s, some even going so far as to posit that his work had underlying left-wing politics. Michael Denning, for example, argues that Hammett’s “stories and characters . in a large part established the hard-boiled aesthetic of the Popular Front” in the 1930s.2 This perspective highlights the danger of seeing Hammett as a writer in the 1930s, instead of the 1920s. -

A Visit with Jack Benny 0Lddmeradio "»Act.R,~ 'DIGESJ' S.,S: .., ~ ~ Old Time Radio No

No.141 Summer ZOU $J.75 A visit with Jack Benny 0ldDmeRadio "»act.R,~ 'DIGESJ' S.,S:_..,~ ~ Old Time Radio No. 141 Summer 2013 "'Fled Allen is tnaklnz cr.acks <1 bo111 ~ bar,g on lht Dt ~nis Day Sho'fl The Old Time Radio Digest 1s pnnted r11,, i lfY is 50 l ltt>n tt/lh mvy_ BOOKS AN D PAPER published and distributed by trery timt he opens his mr:1uu RMS & Associates SOmobo(fy mails • letter. 1ulle 1ii, Den,,;~ :show toniRbt- Allt.11 We have one of the largesc scledions in the USA of out of print Edited by Bob Burchett lt'On't be on it! books and paper items on all aspects of radio broadcast in~. Published qu,nlerly four I1111es a year ------------------·---- ·------· ·--------- -------- One year subscription 1s $15 per year - -- Hooks: A large asso11ment of books on tlw history ofbroacka~ting. Single copies $3.75 each radio writing, stars' biographies. radio sho\, "· and radio play~. Past issues are available. Make checks t;;/.. payable to Old Time Radio Digest. ~,s- Also hooks on broadcasting tcchniqul.'.s. social impact l1f radio etc .. Business and editorial office radio RMS &Assoc,ales, 10280 Gunpowder Rd ~ phcmcra: Material on specific stations. radio scripts, Florence. Kentucky 41 042 advertising literature, radio premiums. NAB anmwl reports, etc. 859.282 0333 -·----------·--- ----- bob [email protected] 6:30 P .M. ORDER OUR CATALOG Advertising rates as of January 1, 2013 ( Jur last cmC1lop, (/12.'i) 11·11s issued in .lufi- .'O I IJ ,md incl11dt•~ o\'l't ./Ofl ,1,•111< Full page ad $20 size 4 5/8 x 7 i11c/11d111y, n 111,e vart,'I)' o.f 1/em , 11 ,, hav1- 11e1·,•r 1een h<'/<,re p/m, cl 1111111/w, of Half page act $10 size 4 5/8 x 3 0/djal'orite.1 that ll'l'/'C llfl/ i11cl11ded Ill (//{/"'"'' colalug Mo.\/ / (('Ill.\ Ill lhi' Hall page ad $10 size2x7 ('(l/(l/og are still (Jvtlllahlt:. -

Dreams, Parables and Hallucinations: the Metaphorical Interludes in Dashiell Hammett's Novels

Rl'l·ista de Es1cu/ios Nor1ea111erícanos, n. º 9 ( 2003 ), pp. 65 - 80 DREAMS, PARABLES AND HALLUCINATIONS: THE METAPHORICAL INTERLUDES IN DASHIELL HAMMETT'S NOVELS JOSÉ ÁNGEL GONZÁLEZ LóPEZ Escuela Oficial de Idiomas (Santander) Dashiell Hammett has generally been regarded as the creator of «realistic» detective fiction ever since Raymond Cbandler used bis works in «The Simple Art of Murder» as the main argument against classic detective fiction: Hammett ... was one of a group - the only one who achieved critica! recognition- who wrote or tried to write realistic mystery fiction .. [he] took murder out of tbe Venetian vase and dropped it into the alley ... gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse ... He put these people down on paper as they were, and he madc them talk in thc language they customarily used for these purposes. ( 13-15) Cbandler's views were based on Hammett's own statements on the pages of Black Mask. where he reminded readers that his stories were based on bis first-hand experience with crime and criminals as opposed to fictional detectives like Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes or S.S. Van Dine's Philo Vanee. But we should not overlook the fact that Hammett had worked in the advertising industry before joining Black Mask, and that he knew very well how to sell a product, including literary products like his own stories. Accordingly, his editor Joseph Shaw wrote introductions to his stories, where he emphasized their «reality»: «If you kili a symbol, no crime is committed and no effect is produced. -

Business Ethos and Gender in Margaret Mitchell's Gone with The

Business Ethos and Gender in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind Krisztina Lajterné Kovács University of Debrecen [email protected] Abstract After the American Civil War, in the Southern agricultural states the rise of capitalist culture and the emergence of a peculiar business ethos in the wake of Reconstruction did not take place without conflicts. Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind dramatizes the outsets of these economic changes which were intertwined with gender aspects, all the more so, since the antebellum Southern system was built on the ideology of radical sexual differences. Scarlett O’Hara emerges as a successful businesswoman whose career mirrors the development of Atlanta to an industrial center. This aspect of the novel, however, is mostly silenced or marginalized in criticism. Now, with the help of the economic and social theories of Max Weber, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Jessica Benjamin, I am reading business and financial success in terms of rationality, irrationality, masculinity, femininity, and violence versus aggressiveness to sketch a portrait of a businessman. Keywords: Gender, Economics, Binary Oppositions, Separate Spheres “If [ Gone with the Wind ] is indeed propaganda, it is not for a return to plantation life and economy, but for the very marketplace, laissez-faire ethic which made Margaret Mitchell so popular” (Adams 59). This comment by Amanda Adams highlights the curious fact that the story of Scarlett O’Hara as she is becoming a successful business(wo)man in Atlanta, which indeed constitutes the -

Movie Time Descriptive Video Service

DO NOT DISCARD THIS CATALOG. All titles may not be available at this time. Check the Illinois catalog under the subject “Descriptive Videos or DVD” for an updated list. This catalog is available in large print, e-mail and braille. If you need a different format, please let us know. Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service 300 S. Second Street Springfield, IL 62701 217-782-9260 or 800-665-5576, ext. 1 (in Illinois) Illinois Talking Book Outreach Center 125 Tower Drive Burr Ridge, IL 60527 800-426-0709 A service of the Illinois State Library Talking Book & Braille Service and Illinois Talking Book Centers Jesse White • Secretary of State and State Librarian DESCRIPTIVE VIDEO SERVICE Borrow blockbuster movies from the Illinois Talking Book Centers! These movies are especially for the enjoyment of people who are blind or visually impaired. The movies carefully describe the visual elements of a movie — action, characters, locations, costumes and sets — without interfering with the movie’s dialogue or sound effects, so you can follow all the action! To enjoy these movies and hear the descriptions, all you need is a regular VCR or DVD player and a television! Listings beginning with the letters DV play on a VHS videocassette recorder (VCR). Listings beginning with the letters DVD play on a DVD Player. Mail in the order form in the back of this catalog or call your local Talking Book Center to request movies today. Guidelines 1. To borrow a video you must be a registered Talking Book patron. 2. You may borrow one or two videos at a time and put others on your request list. -

Open Tiffany Wesner Thesis Final

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DIVISION OF HUMANITIES, ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES GONE WITH THE WIND AND ITS ENDURING APPEAL TIFFANY WESNER SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Baccalaureate Degree in American Studies with honors in American Studies Reviewed and approved* by the following: Raymond Allan Mazurek Associate Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Sandy Feinstein Associate Professor of English Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The white antebellum woman has occupied an evolving archetypal status in American culture throughout the twentieth century. In 1936, Margaret Mitchell published Gone with the Wind and extended the tradition of featuring Southern belles in novels. However, Mitchell chose to alter stereotypical depictions of her heroine and incorporate a theme of survival. Her main character, Scarlett O'Hara, was a prototypical Southern woman of her day. Scarlett was expected to conform to rigidly defined social boundaries but, through acts of defiance and independence, she forged new paths for herself and her family along her route to survival. This thesis investigates the 1939 film adaptation of Mitchell's novel and the contributions of David O. Selznick, Vivien Leigh, and Hattie McDaniel to the story that chronicled Scarlett's transformation from stereotypical Southern belle to independent survivor. This analysis demonstrates that Scarlett depicted the new Southern Woman whose rising to define a diversity of roles embodied the characteristics of the New Woman. The film’s feminist message, romantic grandeur, ground-breaking performances, themes of survival through times of crisis, and opulent feminine appeal all combined in Gone With the Wind to create an American classic with enduring appeal. -

Gone with the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy

Gone With the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy (Tara is the beautiful homeland of Scarlett, who is now talking with the twins, Brent and Stew, at the door step.) BRENT What do we care if we were expelled from college, Scarlett. The war is going to start any day now so we would have left college anyhow. STEW Oh, isn't it exciting, Scarlett? You know those poor Yankees actually want a war? BRENT We'll show 'em. SCARLETT Fiddle-dee-dee. War, war, war. This war talk is spoiling all the fun at every party this spring. I get so bored I could scream. Besides, there isn't going to be any war. BRENT Not going to be any war? STEW Ah, buddy, of course there's going to be a war. SCARLETT If either of you boys says "war" just once again, I'll go in the house and slam the door. BRENT But Scarlett honey.. STEW Don't you want us to have a war? BRENT Wait a minute, Scarlett... STEW We'll talk about this... BRENT No please, we'll do anything you say... SCARLETT Well- but remember I warned you. BRENT I've got an idea. We'll talk about the barbecue the Wilkes are giving over at Twelve Oaks tomorrow. STEW That's a good idea. You're eating barbecue with us, aren't you, Scarlett? SCARLETT Well, I hadn't thought about that yet, I'll...I'll think about that tomorrow. STEW And we want all your waltzes, there's first Brent, then me, then Brent, then me again, then Saul. -

Gone with the Wind and the Lost Cause Caitlin Hall

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2019 Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause Caitlin Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Caitlin, "Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause" (2019). University Honors Program Theses. 407. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/407 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gone with the Wind and the Myth of the Lost Cause An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature. By Caitlin M. Hall Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind is usually considered a sympathetic portrayal of the suffering and deprivation endured by Southerners during the Civil War. I argue the opposite, that Mitchell is subverting the Southern Myth of the Lost Cause, exposing it as hollow and ultimately self-defeating. Thesis Mentor:________________________ Dr. Joe Pellegrino Honors Director:_______________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2019 Department Name University Honors Program Georgia Southern University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements