Politics and the 1920S Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transatlantica, 1 | 2017 a Conversation with Richard Layman 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2017 Morphing Bodies: Strategies of Embodiment in Contemporary US Cultural Practices A Conversation with Richard Layman Benoît Tadié Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/8961 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.8961 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference Benoît Tadié, “A Conversation with Richard Layman”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2017, Online since 29 November 2018, connection on 20 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/ 8961 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.8961 This text was automatically generated on 20 May 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. A Conversation with Richard Layman 1 A Conversation with Richard Layman Benoît Tadié Transatlantica, 1 | 2017 A Conversation with Richard Layman 2 Photograph of Richard Layman The Big Book of the Continental Op, book cover Introduction 1 Richard Layman is the world’s foremost scholar on Dashiell Hammett. Among the twenty books he has written or edited are nine on Hammett, including the definitive bibliography (Dashiell Hammett, A Descriptive Bibliography, 1979), Shadow Man, the first full-length biography (1981), Hammett’s Selected Letters (with Julie M. Rivett, Hammett’s granddaughter, as Associate Editor, 2001), Discovering The Maltese Falcon and Sam Spade (2005, and The Hunter and Other Stories (2013), with Rivett. His books have twice been nominated for the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award. 2 With Rivett, he has recently edited The Big Book of the Continental Op (Vintage Crime/ Black Lizard, 2017), which for the first time gathers the complete canon of Hammett’s first detective, the nameless Continental Op (for Operative). -

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE

Before Bogart: SAM SPADE The Maltese Falcon introduced a new detective – Sam Spade – whose physical aspects (shades of his conversation with Stein) now approximated Hammett’s. The novel also originated a fresh narrative direction. The Op related his own stories and investigations, lodging his idiosyncrasies, omissions and intuitions at the core of Red Harvest and The Dain Curse. For The Maltese Falcon Hammett shifted to a neutral, but chilling third-person narration that consistently monitors Spade from the outside – often insouciantly as a ‘blond satan’ or a smiling ‘wolfish’ cur – but never ventures anywhere Spade does not go or witnesses anything Spade doesn’t see. This cold-eyed yet restricted angle prolongs the suspense; when Spade learns of Archer’s murder we hear only his end of the phone call – ‘Hello . Yes, speaking . Dead? . Yes . Fifteen minutes. Thanks.’ The name of the deceased stays concealed with the detective until he enters the crime scene and views his partner’s corpse. Never disclosing what Spade is feeling and thinking, Hammett positions indeterminacy as an implicit moral stance. By screening the reader from his gumshoe’s inner life, he pulls us into Spade’s ambiguous world. As Spade consoles Brigid O’Shaughnessy, ‘It’s not always easy to know what to do.’ The worldly cynicism (Brigid and Spade ‘maybe’ love each other, Spade says), the coruscating images of compulsive materialism (Spade no less than the iconic Falcon), the strings of point-blank maxims (Spade’s elegant ‘I don’t mind a reasonable amount of trouble’): Sam Spade was Dashiell Hammett’s most appealing and enduring creation, even before Bogart indelibly limned him for the 1941 film. -

The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and Its American Legacy

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 3 (2010) 109–120 The French New Wave and the New Hollywood: Le Samourai and its American legacy Jacqui Miller Liverpool Hope University (United Kingdom) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The French New Wave was an essentially pan-continental cinema. It was influenced both by American gangster films and French noirs, and in turn was one of the principal influences on the New Hollywood, or Hollywood renaissance, the uniquely creative period of American filmmaking running approximately from 1967–1980. This article will examine this cultural exchange and enduring cinematic legacy taking as its central intertext Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai (1967). Some consideration will be made of its precursors such as This Gun for Hire (Frank Tuttle, 1942) and Pickpocket (Robert Bresson, 1959) but the main emphasis will be the references made to Le Samourai throughout the New Hollywood in films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971), The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) and American Gigolo (Paul Schrader, 1980). The article will suggest that these films should not be analyzed as isolated texts but rather as composite elements within a super-text and that cross-referential study reveals the incremental layers of resonance each film’s reciprocity brings. This thesis will be explored through recurring themes such as surveillance and alienation expressed in parallel scenes, for example the subway chases in Le Samourai and The French Connection, and the protagonist’s apartment in Le Samourai, The Conversation and American Gigolo. A recent review of a Michael Moorcock novel described his work as “so rich, each work he produces forms part of a complex echo chamber, singing beautifully into both the past and future of his own mythologies” (Warner 2009). -

Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT ________________ No. 10-1743 ________________ Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc.; * Warner Bros. Consumer Products, * Inc.; Turner Entertainment Co., * * Appellees, * * v. * Appeal from the United States * District Court for the X One X Productions, doing * Eastern District of Missouri. business as X One X Movie * Archives, Inc.; A.V.E.L.A., Inc., * doing business as Art & Vintage * Entertainment Licensing Agency; * Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc.; Leo * Valencia, * * Appellants. * _______________ Submitted: February 24, 2011 Filed: July 5, 2011 ________________ Before GRUENDER, BENTON, and SHEPHERD, Circuit Judges. ________________ GRUENDER, Circuit Judge. A.V.E.L.A., Inc., X One X Productions, and Art-Nostalgia.com, Inc. (collectively, “AVELA”) appeal a permanent injunction prohibiting them from licensing certain images extracted from publicity materials for the films Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz, as well as several animated short films featuring the cat- and-mouse duo “Tom & Jerry.” The district court issued the permanent injunction after granting summary judgment in favor of Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc., Warner Bros. Consumer Products, Inc., and Turner Entertainment Co. (collectively, “Warner Bros.”) on their claim that the extracted images infringe copyrights for the films. For the reasons discussed below, we affirm in part, reverse in part, and remand for appropriate modification of the permanent injunction. I. BACKGROUND Warner Bros. asserts ownership of registered copyrights to the 1939 Metro- Goldwyn-Mayer (“MGM”) films The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind. Before the films were completed and copyrighted, publicity materials featuring images of the actors in costume posed on the film sets were distributed to theaters and published in newspapers and magazines. -

Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990)

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM An Introduction Voltaire and Bernstein’s Candide plunge us from a fool’s world of naiveté to a pain- ful world of war, natural disasters, tragedy, fear of commitment, fear of facts, all cast under a cloud of faux sentimentality—yet with a wink towards truth and love. What an honor it is for The Knights to celebrate Leonard Bernstein in his musical home of Tanglewood with a work that encompasses all of his brilliant contradictions. Bernstein was both a man of his century and ahead of his time—socially, politically, and musically—which makes his centennial feel youthful and timely if not timeless. He lived through some of the world’s darkest times of war, fear, and terror, and his outpouring of joy, love, humor, love, generosity, love, and truth spill from him like it has from only a few geniuses before him. “You’ve been a fool, and so have I.... We’re neither pure, nor wise, nor good” (Voltaire, Candide). Bernstein found a fellow optimis- tic jester in Voltaire. Voltaire wrote “It is love; love, the comfort of the human species, the preserver of the universe, the soul of all sentient beings, love, tender love.” Bernstein’s music embodies this senti- ment. Together, they show us many beautiful and joyous puzzle pieces that connect our imperfect best-of-all-possible-worlds. ERIC JACOBSEN, THE KNIGHTS Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) “Candide” A Very Brief History Bernstein composed Candide from 1954 through August 1956, with Hershy Kay assisting with the orchestration; the libretto was by Lillian Hellman, based on the novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme, by Voltaire, the pen name of François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778). -

Cohen, Michael. “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching

JSR_v01i:JSR 12/20/06 8:14 AM Page 31 “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching, and the Repression of the IWW ■ Michael Cohen, University of California, Berkeley It is almost always the case that a “spontaneous” movement of the subaltern classes is accompanied by a reactionary movement of the right-wing of the dom- inant class, for concomitant reasons. An economic crisis, for instance, engenders on the one hand discontent among the subaltern classes and spontaneous mass movements, and on the other conspiracies among the reactionary groups, who take advantage of the objective weakening of the government in order to attempt coup d’Etat. —Antonio Gramsci 1 When the true history of this decade shall be written in other and less troubled times; when facts not hidden come to light in details now rendered vague and obscure; truth will show that on some recent date, in a secluded office on Wall Street or luxurious parlor of some wealthy club on lower Manhattan, some score of America’s kings of industry, captains of commerce and Kaisers of finance met in secret conclave and plotted the enslavement of millions of workers. Today details are obscured. The paper on which these lines are penciled is criss-crossed by the shadow of prison bars; my ears are be-set by the clang of steel doors, the jangle of fetters and the curses of jail guards. Truth, before it can speak, is stran- gled by power. Yet the big fact looms up, like a mountain above the morning mists; organ- ized wealth has conspired to enslave Labor, and—in enforcing its will—it stops at nothing, not even midnight murders and wholesale slaughter. -

America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW

H-HOAC Review: Shapiro on Strang, Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW Discussion published by John Haynes on Monday, August 9, 2021 Dean A. Strang. Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019. 344 pp. $36.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-299-32330-1. Reviewed by Shelby Shapiro (Independent Scholar)Published on H-Socialisms (August, 2021) Commissioned by Gary Roth (Rutgers University - Newark) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56024 Destroying the IWW Interest in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or Wobblies, seems to come in waves: the 1950s saw Fred Thompson’s The I.W.W.: Its First Fifty Years (1955) while the 1960s brought Joyce Kornbluh’s Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology (1964), Robert Tyler’s Rebels of the Woods: The I.W.W. in the Pacific Northwest (1967), Patrick Renshaw’s The Wobblies: The Story of the IWW and Syndicalism in the United States (1967), Ian Turner’s Sydneys’s Burning (1967), and Melvyn Dubofsky’s We Shall Be All (1969), to cite but a few. Entries for the twenty-first century include Lucien van der Walt’s PhD dissertation, “Anarchism and Syndicalism in South Africa, 1904-1921: Rethinking the History of Labour and the Left” (2007); Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW, edited by Peter Cole, David Struthers, and Kenyon Zimmer (2017), and Peter Cole’sBen Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly(2021). -

C464c4 1920.Pdf

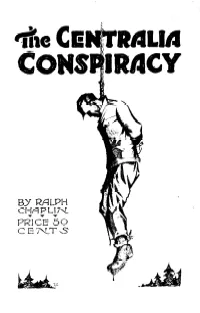

l11111111111111111111llllllllllllllllllnllnlliilllullululllullllllllulllllllllllllllllllilllilllllllllllllllllllullllllllllllllllulllulull~lllllulllllllluulll~lnlulllnlllulllllllllullilllill~lllllulllllllu~nU 6 e a aongue of JFlam q The martyr cannot be dishonored. Every lash inflicted is a tongue of flame; every prison a more illustrious abode; every burned book or house en- lightens the world; every suppres- sed or expunged word reverberates through the earth from side to side. The minds of men are at last aroused; reason looks out and justifies her own, and malice finds all her work is ruin. It is the whipper who is whipped and the tyrant who is undone.-Emerson. 8 . I1III~llUlll~ll~IIllUllllUlll~lllUUUl~llllUllllUlllllUllllllllllllllUllllllllillll~lllllllliIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIHIIIlllllll!lllllllllllilllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll~ MURDER OR SELF-DEFENSE? HIS BOOKLET is not an apology for murder. It is an honest effort to unravel the tangled mesh of circumstances that led up to the Armistice Day tragedy in Centralia, Washington. The writer is one of those who believe that the tak- ing of human life is justifiable .only in self-defense. Even then the act is a horrible reversion to the brute-to the low plane of savagery. Civilization, to be worthy of the name, must afford other methods of settling human differences than those of blood letting. The nation was shocked on November 11, 1919, to read of the killing of four American Legion men by members of the In- dustrial Workers of the World in Centralia. The capitalist news- papers announced to the world that these unoffending paraders were killed in cold blood-that they were murdered from ambush without’provocation of any kind. If the author were convinced that there was even a slight possibility of this being true, he would not raise ‘his voice to defend the perpetrators of such a coward1 y crime. -

Title Seven Samurai and Silverado

Seven Samurai and Silverado -Kurosawa’s Title Influence on Lawrence Kasdan’s Revival Western- Author(s) DAVIES Brett,J Citation 明治大学国際日本学研究, 9(1): 111-119 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10291/20645 Rights Issue Date 2017-03-31 Text version publisher Type Departmental Bulletin Paper DOI https://m-repo.lib.meiji.ac.jp/ Meiji University 111 【Research Note】 Seven Samurai and Silverado: Kurosawa’s Influence on Lawrence Kasdan’s Revival Western DAVIES, Brett J. Abstract Lawrence Kasdan was one of the most successful American filmmakers of the 1980s. His third work as director, Silverado (1985), has been credited with reviving the Western pic- ture after a decade of dormancy, eschewing 1970s revisionism for a more classic approach to the genre. However, this paper will argue that Kasdan may have been influenced more by Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai than by any Hollywood cowboy film. It will first ex- amine Kasdan’s style and concerns pre-Silverado, before outlining some of the similarities that samurai and Western films historically share. Finally, this paper will highlight some of the specific ways in which Kasdan’s Silverado paid homage to Kurosawa’s Seven Samu- rai, through plot, character and theme. Keywords: Lawrence Kasdan, Akira Kurosawa, Silverado, Seven Samurai, Western film, genre The Early Career of Lawrence Kasdan In the early-1980s, Lawrence Kasdan was one of the most successful screenwriters work- ing in Hollywood. His first produced screenplay was The Empire Strikes Back (1980), widely regarded as the most interesting instalment in George Lucas’s Star Wars series. This was fol- lowed by further work with Lucas, along with director Steven Spielberg, on Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), a screenplay voted one of the “101 Greatest Screenplays” of all-time by the Writers Guild of America (2005). -

Download This

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 United States Department of the Interior z/r/ National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter * N/A for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategones from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________ historic name Fort Peabodv_______________________________________ other names/site number 5SM3805 & 5OR1377__________________________________ 2. Location_________________________________________________ street & number Uncompahqre National Forest______________________ [N/A] not for publication city or town Telluride_________________________________ [ x ] vicinity state Colorado code CO county San Miguel & Ourav code 113 & 091 zip code N/A 3. State/Federal Agency Certification_________________________________ As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination [ ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property [ X ] meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant [ ] nationally [ X ] statewide [ ] locally. -

Seven Samurai Rip Offs

Seven Samurai rip offs- 13th Warrior The Magnificent Seven Ronin Dirty Dozen Saving Private Ryan The Wild Bunch Conan the Barbarian (1982) Battle Beyond the Stars Last Man Standing /Yojimbo The Bodyguard, Kevin Costner watches a screening of Kurosawa's film and later does some samurai-ish turns with a sword (Yojimbo, loosely translated, is Japanese for "bodyguard"). THE FILMS of Akira Kurosawa have always been a point at which Eastern and Western currents crossed. His Throne of Blood (1957) retold Macbeth, and Ran (1985) resembled King Lear. And Kurosawa hasn't borrowed only from high art. His thriller High and Low (1963) was an adaptation of 87th-precinct creator Ed McBain's novel King's Ransom. Western filmmakers have returned the compliment, if it can be considered such. Kurosawa's The Seven Samurai (1954) was turned into the 1960 Western hit The Magnificent Seven, and Rashomon (1950) was clumsily translated into Martin Ritt's The Outrage (1964). Although Kurosawa's borrowings from Shakespeare and McBain were acknowledged, The Magnificent Seven and The Outrage were made without the master's approval or even his knowledge. Kurosawa apparently reached his limit with A Fistful of Dollars and sued in an Italian court. Leone, incredibly, denied the connection between his film and Yojimbo, even though numerous critics have pointed out the similarities not only in plot but in shot selection and camera angles. After the suit dragged on for years, Kurosawa finally received a portion of the profits from A Fistful of Dollars and the copyrights to Yojimbo, while United Artists, Leone's distributor, retained copyrights to A Fistful of Dollars. -

A Visit with Jack Benny 0Lddmeradio "»Act.R,~ 'DIGESJ' S.,S: .., ~ ~ Old Time Radio No

No.141 Summer ZOU $J.75 A visit with Jack Benny 0ldDmeRadio "»act.R,~ 'DIGESJ' S.,S:_..,~ ~ Old Time Radio No. 141 Summer 2013 "'Fled Allen is tnaklnz cr.acks <1 bo111 ~ bar,g on lht Dt ~nis Day Sho'fl The Old Time Radio Digest 1s pnnted r11,, i lfY is 50 l ltt>n tt/lh mvy_ BOOKS AN D PAPER published and distributed by trery timt he opens his mr:1uu RMS & Associates SOmobo(fy mails • letter. 1ulle 1ii, Den,,;~ :show toniRbt- Allt.11 We have one of the largesc scledions in the USA of out of print Edited by Bob Burchett lt'On't be on it! books and paper items on all aspects of radio broadcast in~. Published qu,nlerly four I1111es a year ------------------·---- ·------· ·--------- -------- One year subscription 1s $15 per year - -- Hooks: A large asso11ment of books on tlw history ofbroacka~ting. Single copies $3.75 each radio writing, stars' biographies. radio sho\, "· and radio play~. Past issues are available. Make checks t;;/.. payable to Old Time Radio Digest. ~,s- Also hooks on broadcasting tcchniqul.'.s. social impact l1f radio etc .. Business and editorial office radio RMS &Assoc,ales, 10280 Gunpowder Rd ~ phcmcra: Material on specific stations. radio scripts, Florence. Kentucky 41 042 advertising literature, radio premiums. NAB anmwl reports, etc. 859.282 0333 -·----------·--- ----- bob [email protected] 6:30 P .M. ORDER OUR CATALOG Advertising rates as of January 1, 2013 ( Jur last cmC1lop, (/12.'i) 11·11s issued in .lufi- .'O I IJ ,md incl11dt•~ o\'l't ./Ofl ,1,•111< Full page ad $20 size 4 5/8 x 7 i11c/11d111y, n 111,e vart,'I)' o.f 1/em , 11 ,, hav1- 11e1·,•r 1een h<'/<,re p/m, cl 1111111/w, of Half page act $10 size 4 5/8 x 3 0/djal'orite.1 that ll'l'/'C llfl/ i11cl11ded Ill (//{/"'"'' colalug Mo.\/ / (('Ill.\ Ill lhi' Hall page ad $10 size2x7 ('(l/(l/og are still (Jvtlllahlt:.