Why Atlanta for the Permanent Things?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Scarlet O' Hara's Ambitions in Margaret Mitchell's Gone

Chapter 3 The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions and Her Ways to Obtain Them I begin the analysis by revealing the factors of O’Hara’s two ambitions, namely the willingness to rebuild Tara and the desire to win Wilkes’ love. I divide this chapter into two main subchapters. The first subchapter is about the factors of the two ambitions that Scarlett O’Hara has, whereas the second subchapter explains how she tries to accomplish those ambitions. 3.1. The Factors of Scarlett O’Hara’s Ambitions The main female character in Gone with the Wind has two great ambitions; her desires to preserve the family plantation called Tara, and to win Ashley Wilkes’ love by supporting his family’s needs. Scarlett O’Hara herself confesses that “Every part of her, almost everything she had ever done, striven after, attained, belonged to Ashley, were done because she loved him. Ashley and Tara, she belonged to them” (Mitchell, 1936, p.826). I am convinced that there are many factors which stimulate O’Hara to get these two ambitions. Thus, I use the literary tools: the theories of characterization, conflict and setting to analyze the factors. 3.1.1. The Ambition to Preserve Tara Scarlett O’Hara’s ambition to preserve the family’s plantation is stimulated by many factors within her life. I divide the factors that incite Scarlett O’Hara’s ambitions into two parts, the factors found before the war and after. The factors before the war are the sense of belonging to her land, the Southern tradition, and Tara which becomes the source of income. -

Web Book Club Sets

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

"Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History Annjeanette C. Rose College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Rose, Annjeanette C., "Remembering to Forget: "Gone with the Wind", "Roots", and Consumer History" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625795. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-g6vx-t170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMEMBERING TO FORGET: GONE WITH THE WIND. ROOTS. AND CONSUMER HISTORY A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the American Studies Program The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Anjeanette C. Rose 1993 for C. 111 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CJ&52L- Author Approved, April 1993 L _ / v V T < Kirk Savage Ri^ert Susan Donaldson TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................. v ABSTRACT.........................................................................................................................vi -

Experience Atlanta's True South

Experience Atlanta’s True South Clayton County, Georgia Official Home of Gone With the Wind Clayton County, Georgia is located just 15 miles south of Atlanta. Here, visitors will find the small town charm and southern hospitality that they expect. Whether its the convenience of being a few miles from the world’s busiest airport, the excitement of the Atlanta Motor Speedway, the lure of antebellum homes and museums, the history of Stately Oaks Plantation or the heritage at the State and National Archives - Clayton County, Georgia is Atlanta’s True South! What’s New and What’s News in Atlanta’s True South Official Home of Gone With the Wind Clayton County, Georgia is the Official Home of Gone With the Wind. On the first few pages of Margaret Mitchell’s world-renowned novel, Scarlett’s beloved home, Tara, is set in Jonesboro, Georgia. Clayton County is a part of the Gone With the Wind Trail, a state designated trail for visitors to follow, linking sites dedicated to Mar- garet Mitchell, her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel and the subsequent film. Featured sites include the Road to Tara Museum, Margaret Mitchell House, Atlanta Fulton County Public Library Oakland Cemetery and the Marietta Gone With the Wind Museum. Local Character Peter Bonner - Local historian and owner of Historical & Hysterical Tours, Peter brings life, laughter and fun into learning more about Gone With the Wind, the real people who inspired Mar- garet Mitchell’s famed characters and the pivotal Battle of Jonesboro. Birders’ Paradise The Newman Wetlands Center, a man-made 32-acre habitat and wetlands area, is home to waterfowl, raptors, song birds and more. -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

Interpretation of Scarlett's Land Complex in Gone with the Wind

102 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN ENGINEERING AND SOCIETY, VOL.1, NO.4, Interpretation of Scarlett‘s Land Complex in Gone with the Wind from the Perspective of Humanity Shutao Zhou College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University, Daqing 163319, China [email protected] Abstract: The famous novel Gone with the Wind by Tara was leisurely and wealthy. In this context, a Margaret Mitchell takes the Civil War as the young girl who was just sixteen years old lived a background. With the three marriage experiences of carefree life without a single worry, and the only Scarlett as the main line, her strong feeling of land thing she thought of was how to attract the attention complex runs through the whole book. The red land of men. She did not realize the importance of land at at Tara witnessed Scarlett‘s gradual growth and all. maturity, revealing the eternal blood ties between When her father persuaded Scarlett to give up her land and Scarlett. This paper, by analyzing Scarlett‘s obsession with Ashley and give Tara to her, she life course, explores the development of the land would not mind or even be hostile to the idea of complex which is a process from unconsciousness to being the master of the land. As her father gave her fight for the land. Scarlett‘s land complex gave her a the generous gift, she said in fury, ―I wouldn‘t have vivid image. Cade on a silver tray,‖ ―And I wish you‘d quit Key words: Scarlett; Tara; Land Complex pushing him at me! I don‘t want Tara or any old plantation. -

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3. -

Artist's Resume

R O B E R T S H E R E R [email protected] www.robertsherer.com ___________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION 1989-92 Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.) degree, Painting. Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, Edinboro, PA. 1987-88 Post-Baccalaureate Independent Study, Advanced Painting, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI. 1982-86 Bachelor of Fine Arts (B.F.A.) degree, Drawing and Painting, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA. 1979-80 Foundation Studies Program, Visual Art, Atlanta College of Art, Atlanta, GA. 1976-78 Arts and Science (A.S.) degree, Visual Art, Walker College, Jasper, AL. SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2014 - Art, AIDS, America, Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA. (invitational) 2013 - Head, Shoulders, Genes, and Toes, FSU Museum of Fine Arts, Tallahassee, FL. (invitational) 2012 - Permanent Collection, Davis Lisboa Museum of Contemporary Art, Barcelona, Spain. (collection) - Robert Sherer: American Pyrography, Lyman-Eyer Gallery, Provincetown, MA. (solo) - 30x30 No. 10, Gruppenaustellung, Galerie Kunstbehandlung. KG, Munich, Germany. (group) - Centennial Ball Auction, Alliance Française d'Atlanta, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - 17th Annual Hambidge Center Gala, Goat Farm Art Center, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - Summer Group Show, Lyman-Eyer Gallery, Provincetown, MA. (group) - Evening for Equality, Equality Foundation of Georgia, Twelve Hotel, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - Selected Blood Works: Robert Sherer, Lyman-Eyer Gallery, Provincetown, MA. (solo) - Faculty Exhibition, Fine Arts Gallery, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA. (group) - Art Papers Auction, Mason Murer Gallery, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - 30x30 No.10, Gruppenaustellung, Galerie Kunstbehandlung. KG, Munich, Germany. (group) - Hidden and Forbidden Identities, ArtExpo International, Palazzo Albrizzi, Venice, Italy (juried) - Georgia Lawyers for the Arts - 35th Annual Gala, King Plow Art Center, Atlanta, (invitational) - Gallery Artists, Galerie Kunstbehandlung. -

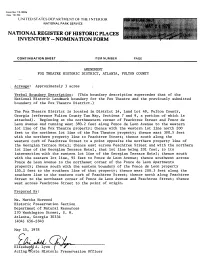

Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300a (Hev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM CONTIIMU ATION SHEET ITEM NUMBER PAGE AMENDMENT FOX THEATRE HISTORIC DISTRICT, ATLANTA, FULTON COUNTY Acreage; Approximately 3 acres ) Verbal Boundary Description; (This boundary description supercedes that of the National Historic Landmark boundary for the Fox Theatre and the previously submitted boundary of the Fox Theatre District.) The Fox Theatre District is located in District 14, Land Lot 49, Fulton County, Georgia (reference Fulton County Tax Map, Sections 7 and 9, a portion of which is attached). Beginning at the northwestern corner of Peachtree Street and Ponce de Leon Avenue and running west 380.2 feet along Ponce de Leon Avenue to the western lot line of the Fox Theatre property; thence with the western lot line north 200 feet to the northern lot line of the Fox Theatre property; thence east 388.5 feet with the northern property line to Peachtree Street; thence south along the western curb of Peachtree Street to a point opposite the northern property line of the Georgian Terrace Hotel; thence east across Peachtree Street and with the northern lot line of the Georgian Terrace Hotel, that lot line being 201 feet, to its intersection with the eastern lot line of the Georgian Terrace Hotel; thence south with the eastern lot line, 95 feet to Ponce de Leon Avenue; thence southwest across Ponce de Leon Avenue to the northeast corner of the Ponce de Leon Apartments property; thence south with the eastern boundary of the Ponce de Leon property 155.1 feet to the southern line of that property; thence west 208.3 feet along the southern line to the eastern curb of Peachtree Street; thence north along Peachtree Street to the northeast corner of Ponce de Leon Avenue and Peachtree Street; thence west across Peachtree Street to the point of origin. -

Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Technology Faculty Publications Jan. 2015) 2013 Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix Chara Haeussler Bohan Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_facpub Part of the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Nix, J. & Bohan, C. H. (2013). Reaching across the color line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an uncommon friendship. Social Education, 77(3), 127–131. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Jan. 2015) at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Education 77(3), pp 127–131 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Reaching across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix and Chara Haeussler Bohan In 1940, Atlanta was a bustling town. It was still dazzling from the glow of the previous In Atlanta, the color line was clearly year’s star-studded premiere of Gone with the Wind. The city purchased more and drawn between black and white citizens. -

Margaret Mitchell Letter and Program

Margaret Mitchell letter and program Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Mitchell, Margaret, 1900-1949. Title: Margaret Mitchell letter and program Dates: 1940 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0919 Biographical/Historical Note Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949) was born in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father, Eugene M. Mitchell, was a prominent attorney. Her mother, Maybelle Stephens Mitchell, was active in the women's suffrage movement. Margaret Mitchell attended Atlanta public schools, graduated from Washington Seminary in Atlanta, and attended Smith College for one year before leaving college upon the death of her mother. She married John Marsh on July 4, 1925. Her only novel, Gone With the Wind, was published in 1936 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937. The movie based on the novel was released in 1939. She was a columnist for the Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine from 1922 until 1926 and wrote dozens of articles, interviews, sketches, and book reviews before publishing her novel. She died in 1949 after being struck by a car while crossing Peachtree Street in Atlanta. Scope and Content Note This collection includes a letter from Margaret Mitchell in Atlanta, Georgia to Joseph W. McAvoy of the Hibernian Society of Savannah, Georgia on March 20, 1940. In her letter, Mitchell thanks McAvoy for the program of the dinner; she also explains why she chose the name "Tara" for the plantation in Gone with the Wind. The second item in the collection is a program of the Hibernian Society Dinner, March 16, 1940, which features a picture of the fictitious plantation, "Tara", on the cover and includes the lyrics to the song, "The Harp that Once Through Tara's Hall." Index Terms Hibernian Society (Savannah, Ga.) Letters (correspondence) McAvoy, Joseph W., b.