The Wind Done Gone: Transforming Tara Into a Plantation Parody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Wind Done Gone Or Rewriting Gone Wrong: Retelling Southern Social, Racial, and Gender Norms Through Parody

The Wind Done Gone or Rewriting Gone Wrong: Retelling Southern Social, Racial, and Gender Norms through Parody. Emmeline Gros To cite this version: Emmeline Gros. The Wind Done Gone or Rewriting Gone Wrong: Retelling Southern Social, Racial, and Gender Norms through Parody.. South Atlantic Review, South Atlantic Modern Language Asso- ciation, 2016, 80 (3-4), pp.136-160. hal-01671950 HAL Id: hal-01671950 https://hal-univ-tln.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01671950 Submitted on 3 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. “Re-vision, the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction is for women more than a chapter in cultural history: it is an act of survival.” (Adrienne Rich 18). The Wind Done Gone or Rewriting Gone Wrong: Retelling Southern Social, Racial, and Gender Norms through Parody. Dr. Emmeline GROS “Any good plot would stand retelling” and “style does not matter so long as you know what the characters are doing” (Farr 14). It is with these words that Margaret Mitchell justified her love for boys’ stories, The Rover Boys, which her brother criticized for their lack of style and their repetitive structure. -

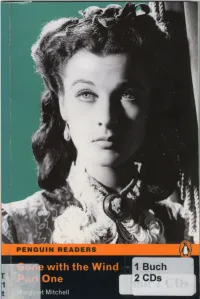

Gone with the Wind Part 1

Gone with the Wind Part 1 MARGARET MITCHELL Level 4 Retold by John Escott Series Editors: Andy Hopkins and Jocelyn Potter Pearson Education Limited Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England and Associated Companies throughout the world. ISBN: 978-1-4058-8220-0 Copyright © Margaret Mitchell 1936 First published in Great Britain by Macmillan London Ltd 1936 This adaptation first published by Penguin Books 1995 Published by Addison Wesley Longman Limited and Penguin Books Ltd 1998 New edition first published 1999 This edition first published 2008 3579 10 8642 Text copyright ©John Escott 1995 Illustrations copyright © David Cuzik 1995 All rights reserved The moral right of the adapter and of the illustrator has been asserted Typeset by Graphicraft Ltd, Hong Kong Set in ll/14pt Bembo Printed in China SWTC/02 All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publishers. Published by Pearson Education Ltd in association with Penguin Books Ltd, both companies being subsidiaries of Pearson Pic For a complete list of the titles available in the Penguin Readers series please write to your local Pearson Longman office or to: Penguin Readers Marketing Department, Pearson Education, Edinburgh Gate, Harlow, Essex CM20 2JE, England. Contents page Introduction V Chapter 1 News of a Wedding 1 Chapter 2 Rhett Butler 7 Chapter 3 Changes 9 Chapter 4 Atlanta 16 Chapter 5 Heroes 23 Chapter 6 Missing 25 Chapter 7 News from Tara 31 Chapter 8 The Yankees Are Coming 36 Chapter 9 Escape from Atlanta 41 Chapter 10 Home 45 Chapter 11 Murder 49 Chapter 12 Peace, At Last 54 Activities 58 Introduction ‘You, Miss, are no lady/ Rhett Butler said. -

Happy 75Th Anniversary

Literature County girlhood home, Tara. Clayton County was designated the official home of Gone with the Wind by Mitchell’s brother Stephens. All around were signs that this is truly GWTW country: Tara Elementary School, Tara Wedding Chapel, Tara Gone with the Wind Florist and – well, you get the idea. The county has even had a couple of Scarletts: Melly Meadows, a striking Vivien Leigh lookalike who traveled worldwide in this role, delighting Happy 75th Anniversary everyone she meets with her fiddle-dee-dees and, more recently, By Lillian Africano Cynthia Evans. My GWTW orientation began at the Road to Tara Museum, housed in the 1867 Jonesboro Railroad Station, Gone with the Wind about 15 miles south of Atlanta. Movie Set This relatively small museum has BELOW Gone with the Wind drawn Windies from all over the Movie Poster world; the guest book includes visitors from Norway, Finland, Sweden, New Zealand, Australia, largest collections of GWTW At the Patrick Cleburne Memorial the U.K., China and Japan. autographed photos. Olivia de Confederate Cemetery, where some Haviland, who played Melly and who 1,000 fallen soldiers from the Battle Here is so much to delight the most celebrated her 98th birthday in July, of Jonesboro are buried, Bonner, who dedicated fan: first editions of the is here of course, but so are the has taken part in past re-enactments novel, autographed photos, costumes movie’s bit players, such as the of the battle, vividly described the (including the pantalets worn by Tarleton twins. (Actor George ferocity of the two-day combat. -

2015-Pre-Conference-Magazine.Pdf

From the desk of Laurie N. Robinson Haden Founder & CEO Corporate Counsel Women of Color® I am proud to report that our Atlanta Eleventh Annual more. We will discuss what legal department leaders are Career Strategies Conference (September 23-25, 2015) is actually doing to foster the advancement of women of col- SOLD OUT! or at their companies (through recruitment, retention, and advancement). We will hear from Ricardo A. Anzaldua Through your continued support, the growth of the orga- (MetLife), Lori A. Schechter (McKesson), Audrey Boone nization has been tremendous. Over the years, we have Tillman (Aflac Incorporated), Teresa Wynn Roseborough helped numerous attorneys of color to advance their ca- (The Home Depot), and Sari Dweck (Thomson Reuters), reers in corporate America. Recently, we surpassed 3,300 and other dynamic speakers. members around the world. We thank the in-house leaders who have helped to institutionalize our conference at their Further, we will honor Leslie M. Turner (Senior Vice Presi- companies by actively including CCWC in their recruiting dent, General Counsel and Secretary, The Hershey Compa- efforts to find a diverse slate of candidates and by support- ny) with our Diamond Award of Excellence. Also, attendees ing the diverse attorneys they send to our conference year will hear from luminaries including Commissioner Sharon Y. after year. Bowen (U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission), Dr. Yvonne Thompson CBE (CEO, ASAP Communications), I would like to thank our corporate and law firm spon- Malvina Camejo Longoria (Group Executive and Associ- sors who make the growth and expansion of our con- ate General Counsel, MasterCard), Jacqueline Berrien (for- ference possible. -

An Incredible Investment Opportunity the Twelve Oaks in a Truly

An Incredible Investment Opportunity The Twelve Oaks in a truly exceptional business opportunity. It is already income-producing, profitable, and award-winning. There are four different avenues for producing revenue with all permits already in place: as a Bed & Breakfast, an event venue, a historic site offering tours, and as a location for filming located right in the heart of the original “Hollywood of the South” in Covington, GA, which is an area for tremendous growth and part of the metro Atlanta area. The world’s busiest international airport is just 38 miles from the property and Covington houses its own regional airport as well. Georgia welcomes over 100 million tourists per year1 and approximately 50 million visit the Atlanta area. Income Opportunities: 1. Bed & Breakfast/Luxury Inn: The property opened as a Bed & Breakfast for the first time in late 2012. Every year since opening has brought tremendous growth and unheard of awards for a “new” inn. Some of the awards won and recognitions received follow: • Southern Living South’s Best Inns: Just last year (2018), the readers of Southern Living voted the Twelve Oaks as one of the South’s Best Inns in the #4 spot! This is amazing as a relatively “new” inn opened just six years prior beat out places like The Cloister, Blackberry Farm, Grove Park Inn, etc. • Tripadvisor Hall of Fame (2019 and 2018). Every year Tripadvisor gives a Certificate of Excellence to places with amazing reviews. The Twelve Oaks has received a Certificate of Excellence for every single year in business and was thus inducted into the “Hall of Fame” in 2018 and just received the designation for 2019 as well. -

Stereotypes, Sexuality, and Intertextuality in Alice Randall's The

Language, Literature, and Interdisciplinary Studies (LLIDS) ISSN: 2547-0044 ellids.com/archives/2018/12/2.2-Woltmann.pdf CC Attribution-No Derivatives 4.0 International License www.ellids.com Stereotypes, Sexuality, and Intertextuality in Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone Suzy Woltmann Towards the end of Alice Randall’s 2001 novel The Wind Done Gone (TWDG), the reader is confronted by an epistolary inclusion: the narrator’s mother, Mammy, writes from beyond the grave to negotiate a marriage proposal for her daughter. Mammy’s voice is clear. As Cy- nara, the narrator, tells us, “...syllable and sound, the words were Mammy’s” (162). TWDG retells the history of Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (GWTW), along with the inclusion of Mammy’s voice and identity as something far beyond being a mere appendage to GWTW’s protagonist, Scarlett. In similar ways, Randall gives voice to characters that lacked agency in GWTW and in doing so infuses them with complex personhood. TWDG’s countercultural approach signifies other literary works, especially its source text and slave narratives. The paper argues that TWDG intertextually parodies the portrayal of stereotypes and sexuality found in GWTW and highlights the African- American literary tradition through its use of irony, signposting front cover portraiture, and confirmation documents found in slave narra- tives. By doing so, the adaptation illustrates the continued haunting presence of slavery in today’s cultural imagination and pushes against its ideological effects. This matters because Cheryl Wall, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Avery Gordon, and others show, African-American authors often rely on significant past works that constitute a sort of literary tra- dition highlighting racist discourse rather than analyzing the continu- ing and contemporary relevance of the horrors of slavery. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Alice Randall

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Alice Randall Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Alice Randall Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Alice Randall Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Alice Randall, Dates: March 17, 2007 Bulk Dates: 2007 Physical Description: 9 Betacam SP videocassettes (4:06:54). Abstract: Fiction writer, lyricist, and screenwriter Alice Randall (1959 - ) wrote New York Times bestseller "The Wind Done Gone." Randall is the first African American woman to have a number one country hit ("XXX's and OOO's: An American Girl"). Randall was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on March 17, 2007, in Nashville, Tennessee. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2007_094 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Fiction writer, lyricist, and screenwriter Alice Randall was born to Mari-Alice and George Randall on May 4, 1959 in Detroit, Michigan. She spent her early years in Detroit where she attended St. Phillips Lutheran School and Greenfield Peace Lutheran School. Moving with her mother to Washington, D.C., she was enrolled at Amidon Elementary School and graduated from Georgetown Day School. Briefly traveling to Great Britain to enroll in the Institute of Archaeology at the University of London, she returned to enter Harvard University in the fall of 1977. At Harvard, she was influenced by Hubert Matos, Harry Levin and Nathan Irving Huggins and was a member of the International Relations Council. -

Gone with the Wind and the Imagined Geographies of the American South Taulby H. Edmondson Dissertation Submitt

The Wind Goes On: Gone with the Wind and the Imagined Geographies of the American South Taulby H. Edmondson Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Emily M. Satterwhite, Co-Chair David P. Cline, Co-Chair Marian B. Mollin Scott G. Nelson February 13, 2018 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Gone with the Wind, Mass Media and History, US South, Slavery, Civil War, Reconstruction, African American History, Memory, Race Relations, Whiteness, Nationalism, Tourism, Audiences Copyright: Taulby H. Edmondson 2018 The Wind Goes On: Gone with the Wind and the Imagined Geographies of the American South Taulby H. Edmondson ABSTRACT Published in 1936, Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind achieved massive literary success before being adapted into a motion picture of the same name in 1939. The novel and film have amassed numerous accolades, inspired frequent reissues, and sustained mass popularity. This dissertation analyzes evidence of audience reception in order to assess the effects of Gone with the Wind’s version of Lost Cause collective memory on the construction of the Old South, Civil War, and Lost Cause in the American imagination from 1936 to 2016. By utilizing the concept of prosthetic memory in conjunction with older, still-existing forms of collective cultural memory, Gone with the Wind is framed as a newly theorized mass cultural phenomenon that perpetuates Lost Cause historical narratives by reaching those who not only identify closely with it, but also by informing what nonidentifying consumers seeking historical authenticity think about the Old South and Civil War. -

Copy This Essay: How Fair Use Doctrine Harms Free Speech and How Copying Serves It

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2004 Copy This Essay: How Fair Use Doctrine Harms Free Speech and How Copying Serves It Rebecca Tushnet Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/797 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1793181 114 Yale L.J. 535-590 (2004) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons TUSHNET_POST_FLIP2.DOC 12/1/2004 6:05:00 PM Essay Copy This Essay: How Fair Use Doctrine Harms Free Speech and How Copying Serves It Rebecca Tushnet† CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 537 I. OVERVIEW: THE FIRST AMENDMENT, COPYRIGHT, AND THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THEM ................................................................ 538 A. What Free Speech Is For ............................................................. 538 B. Copyright and Fair Use............................................................... 540 C. The First Amendment Value of Copying...................................... 545 II. LIMITING THE FIRST AMENDMENT BY INVOKING FAIR USE .............. 547 A. How the First Amendment Value of Dissent Maps onto Transformative Fair Use............................................................. -

Gone with the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy

Gone With the Wind Chapter 1 Scarlett's Jealousy (Tara is the beautiful homeland of Scarlett, who is now talking with the twins, Brent and Stew, at the door step.) BRENT What do we care if we were expelled from college, Scarlett. The war is going to start any day now so we would have left college anyhow. STEW Oh, isn't it exciting, Scarlett? You know those poor Yankees actually want a war? BRENT We'll show 'em. SCARLETT Fiddle-dee-dee. War, war, war. This war talk is spoiling all the fun at every party this spring. I get so bored I could scream. Besides, there isn't going to be any war. BRENT Not going to be any war? STEW Ah, buddy, of course there's going to be a war. SCARLETT If either of you boys says "war" just once again, I'll go in the house and slam the door. BRENT But Scarlett honey.. STEW Don't you want us to have a war? BRENT Wait a minute, Scarlett... STEW We'll talk about this... BRENT No please, we'll do anything you say... SCARLETT Well- but remember I warned you. BRENT I've got an idea. We'll talk about the barbecue the Wilkes are giving over at Twelve Oaks tomorrow. STEW That's a good idea. You're eating barbecue with us, aren't you, Scarlett? SCARLETT Well, I hadn't thought about that yet, I'll...I'll think about that tomorrow. STEW And we want all your waltzes, there's first Brent, then me, then Brent, then me again, then Saul. -

Gone with the Wind and the Lost Cause Caitlin Hall

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2019 Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause Caitlin Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Caitlin, "Gone with the Wind and The Lost Cause" (2019). University Honors Program Theses. 407. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/407 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gone with the Wind and the Myth of the Lost Cause An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Literature. By Caitlin M. Hall Under the mentorship of Joe Pellegrino ABSTRACT Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind is usually considered a sympathetic portrayal of the suffering and deprivation endured by Southerners during the Civil War. I argue the opposite, that Mitchell is subverting the Southern Myth of the Lost Cause, exposing it as hollow and ultimately self-defeating. Thesis Mentor:________________________ Dr. Joe Pellegrino Honors Director:_______________________ Dr. Steven Engel April 2019 Department Name University Honors Program Georgia Southern University 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements -

Learn More at Chester County Juneteenth Festival Keynote Speakers Journeying Towards Freedom

Chester County Juneteenth Festival Journeying Towards Freedom C hester County, Pennsylvania, plans a county-wide commemoration of Juneteenth, the oldest-known celebration of the ending of slavery in the United States. Four partners ---the Chester County Historic Preservation Society, Voices Underground, the Chester County History Center, and the Chester County Planning Commission – are working together to present an array of programs and public events that honor the courage and commitment of residents, past and present, in support of freedom and equality for all. Juneteenth 2021 will highlight the history of Chester County’s role in the Under- ground Railroad and the Anti-Slavery movement. In the mid-19th century, Chester County became a hotbed for the Underground Railroad, with free Blacks, escaping slaves, and White abolitionists working together to aid runaways on their perilous journey to freedom. This commitment to social justice has continued through the County’s history, seen in decades of brave efforts to secure equal rights and social justice that continue to echo in today’s campaigns. The Festival will kick off on June 12 with a United Faith Community Celebration, led by area clergy. The Festival ‘s keynote events will take place in and around Kennett Square the weekend of June 18, featuring nationally-known speakers, performances, gatherings, and tours. The annual Town Tours and Village Walks, all dedicated to the Festival’s theme, will begin on June 17. Local programs and celebrations will be held in communities across the County from June 12 through July 3 and will include an array of visits to historic sites, walking tours, speakers, and family programs.