Atlanta's Marketplace for Gone with the Wind Memory Jennifer Word Dickey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Objectivity, Interdisciplinary Methodology, and Shared Authority

ABSTRACT HISTORY TATE. RACHANICE CANDY PATRICE B.A. EMORY UNIVERSITY, 1987 M.P.A. GEORGIA STATE UNIVERSITY, 1990 M.A. UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- MILWAUKEE, 1995 “OUR ART ITSELF WAS OUR ACTIVISM”: ATLANTA’S NEIGHBORHOOD ARTS CENTER, 1975-1990 Committee Chair: Richard Allen Morton. Ph.D. Dissertation dated May 2012 This cultural history study examined Atlanta’s Neighborhood Arts Center (NAC), which existed from 1975 to 1990, as an example of black cultural politics in the South. As a Black Arts Movement (BAM) institution, this regional expression has been missing from academic discussions of the period. The study investigated the multidisciplinary programming that was created to fulfill its motto of “Art for People’s Sake.” The five themes developed from the program research included: 1) the NAC represented the juxtaposition between the individual and the community, local and national; 2) the NAC reached out and extended the arts to the masses, rather than just focusing on the black middle class and white supporters; 3) the NAC was distinctive in space and location; 4) the NAC seemed to provide more opportunities for women artists than traditional BAM organizations; and 5) the NAC had a specific mission to elevate the social and political consciousness of black people. In addition to placing the Neighborhood Arts Center among the regional branches of the BAM family tree, using the programmatic findings, this research analyzed three themes found to be present in the black cultural politics of Atlanta which made for the center’s unique grassroots contributions to the movement. The themes centered on a history of politics, racial issues, and class dynamics. -

The Atlanta Preservation Center's

THE ATLANTA PRESERVATION CENTER’S Phoenix2017 Flies A CELEBRATION OF ATLANTA’S HISTORIC SITES FREE CITY-WIDE EVENTS PRESERVEATLANTA.COM Welcome to Phoenix Flies ust as the Grant Mansion, the home of the Atlanta Preservation Center, was being constructed in the mid-1850s, the idea of historic preservation in America was being formulated. It was the invention of women, specifically, the ladies who came J together to preserve George Washington’s Mount Vernon. The motives behind their efforts were rich and complicated and they sought nothing less than to exemplify American character and to illustrate a national identity. In the ensuing decades examples of historic preservation emerged along with the expanding roles for women in American life: The Ladies Hermitage Association in Nashville, Stratford in Virginia, the D.A.R., and the Colonial Dames all promoted preservation as a mission and as vehicles for teaching contributive citizenship. The 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition held in Piedmont Park here in Atlanta featured not only the first Pavilion in an international fair to be designed by a woman architect, but also a Colonial Kitchen and exhibits of historic artifacts as well as the promotion of education and the arts. Women were leaders in the nurture of the arts to enrich American culture. Here in Atlanta they were a force in the establishment of the Opera, Ballet, and Visual arts. Early efforts to preserve old Atlanta, such as the Leyden Columns and the Wren’s Nest were the initiatives of women. The Atlanta Preservation Center, founded in 1979, was championed by the Junior League and headed by Eileen Rhea Brown. -

Furman Vs Clemson (9/10/1988)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1988 Furman vs Clemson (9/10/1988) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Furman vs Clemson (9/10/1988)" (1988). Football Programs. 195. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/195 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. $2.00 September 10, 1988 Clemson Football *88 i \i\ii<sin Clemson vs. Furman Memorial Stadium Bullish Blockers MANGE YOU WORTHY OF THE BEST? Batson is the exclusive U.S. agent for textile equipment from the leading textile manufacturers worldwide. Experienced people back up our sales with complete service, spare parts, technical assistance, training and follow-up. DREF 3 FRICTION SPINNING MACHINE delivers yarn to 330 ypm. i FEHRER K-21 RANDOM CARDING MACHINE has weight range ^ 2 10-200 g/m , production speedy | m/min. rttfjfm 1 — •• fj := * V' " VAN DE WIELE PLUSH WEAVING MACHINES weave apparel, DORNIER RAPIER WEAVING MACHINES are upholstery, carpet. -

Acworth Mill Village Is a Tributary to Proctor Creek, Running Northeast to Southwest, That More Or Less Bisects the Village (Photograph #59)

ACWORTH MILL AND MILL VILLAGE HISTORIC DISTRICT INFORMATION FORM (HDIF) Section 1. General Information Section 2. Description Section 3. History Section 4. Significance Section 5. Supporting Documentation and Checklist Submitted to: National Register Coordinator Historic Preservation Division 254 Washington Street Ground Level Atlanta, GA 30334 Submitted by: Jaime L. Destefano, MS and Michelle K. Taylor, MLA of Environmental Corporation of America SECTION 1 General Information 1. Historic Name of District: Acworth Mill and Mill Village 2. Location of District: The district boundaries include the CSX Railroad along the north, the rear property lines of parcels fronting Toccoa Drive on the east, a triangular parcel of land (4288 S. Main Street) and New McEver Road to the south, and Thomasville Drive and S. Main Street along the west. Addresses of parcels within the district boundaries include the following: 4525 Acworth Industrial Drive 3941-3961 Albany Drive 4445-4503 Clarkdale Drive CSX Railroad Corridor (formerly Western & Atlantic Railroad) 4288, 4424-4458 (even street numbers) South Main Street 4470-4512 Thomasville Drive 4310-4396 Toccoa Drive (even only) 4408-4483 Toccoa Drive City: Acworth County: Cobb Zip Code: 30101 Distance to County Seat of Marietta: ~10 miles 3. Acreage of district to be nominated (approximately): ~55 acres 4. a. Total Number of Historic/Contributing Resources in district: 52 b. Total Number of Noncontributing Resources in district: 7 5. Are a majority of buildings in the district less than 50 years old: No 6. Property Ownership Does a federal agency own property within the district: No Do the property owners within the district support nomination of the district to the National Register? Unknown Explain: As of October 2011, property owners have not been notified of potential National Register nomination. -

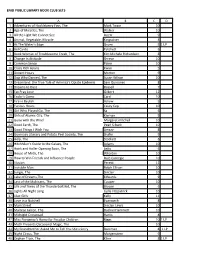

Web Book Club Sets

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

NORTH Highland AVENUE

NORTH hIGhLAND AVENUE study December, 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Study Prepared by the City of Atlanta Department of Planning, Development and Neighborhood Conservation Bureau of Planning In conjunction with the North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force December 1999 North Highland Avenue Transportation and Parking Task Force Members Mike Brown Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Warren Bruno Virginia Highlands Business Association Winnie Curry Virginia Highlands Civic Association Peter Hand Virginia Highlands Business Association Stuart Meddin Virginia Highlands Business Association Ruthie Penn-David Virginia Highlands Civic Association Martha Porter-Hall Morningside-Lenox Park Civic Association Jeff Raider Virginia Highlands Civic Association Scott Riley Virginia Highlands Business Association Bill Russell Virginia Highlands Civic Association Amy Waterman Virginia Highlands Civic Association Cathy Woolard City Council – District 6 Julia Emmons City Council Post 2 – At Large CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS VISION STATEMENT Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 1:1 Purpose 1:1 Action 1:1 Location 1:3 History 1:3 The Future 1:5 Chapter 2 TRANSPORTATION OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 2:1 Introduction 2:1 Motorized Traffic 2:2 Public Transportation 2:6 Bicycles 2:10 Chapter 3 PEDESTRIAN ENVIRONMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 3:1 Sidewalks and Crosswalks 3:1 Public Areas and Gateways 3:5 Chapter 4 PARKING OPPORTUNITIES AND ISSUES 4:1 On Street Parking 4:1 Off Street Parking 4:4 Chapter 5 VIRGINIA AVENUE OPPORTUNITIES -

The Church That Christ Built” Sincerely

The Foster Family Dear Big Bethel Family and Friends: I greet you in the Name of our Lord and Savior Jesus the Christ. Today, Big Bethel AME Church - Atlanta’s oldest African American church congregation - celebrates One Hundred Seventy-Two (172) years of worship, fellowship and ministry. Big Bethel has withstood the test of time and yet, God still signifies Big Bethel as a Beacon of Light for downtown Atlanta which still proudly proclaims that “Jesus Saves.” At this time of celebration – let us all give thanks and honor to the glory of God for Big Bethel AME Church. We joyously welcome Bishop John Richard Bryant as our anniversary preacher. We welcome Bishop Bryant and his guests to Big Bethel AME Church. Please allow me to give God praise for our Church Anniversary Chairpersons: Sis. Nannette McGee, Sis. Geri Dod- son, Sis. Roz Thomas. Let me also thank the entire Church Anniversary committee for a job well done!!! We thank God again for all of the wonderful Anniversary Month activities - the Tailgate Kickoff Sunday, the Pilgrimage to Oak- land Cemetery, the Youth History Program, the Revival Week, the Trinity Table Weekend, the Kwanzaa-Sol and Mime Anniversary Concert and the Children Sabbath Weekend. Sis. Mary Ann, Kristina (Dewey and Zoey), John Jr. and Jessica join me in wishing our ‘Big Bethel Family’ a blessed 172nd Anniversary!!! “The Church that Christ Built” Sincerely, Rev. John Foster, Ph.D. Senior Pastor 2 Big Bethel AME Church BISHOP JOHN RICHARD BRYANT—RETIRED 106TH ELECTED & CONSECRATED BISHOP OF THE AFRICAN METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH Bishop John Richard Bryant is the son of the late Bishop Harrison James Bryant and Edith Holland Bryant. -

Atlanta History Center HOWARD POUSNER

Atlanta History Center HOWARD POUSNER 76 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • August 2017 t’s safe to say that in its nine-decade history, the Atlanta History Center has never borrowed a phrase from a popular rap song for a marketing slogan. But there it was this spring on a billboard towering over Atlanta’s I-75/85 Downtown Connector, in giant mint-colored letters sharing space with Iblown-up vintage buttons representing Hank Aaron, the Fox Theatre, and other Atlanta icons: “Do It for the Culture.” As part of a bold rebranding, the illuminated bill- Atlanta community of Buckhead in late 2015. Its main board lifted the line from a hit song by Atlanta rappers point of entry, the Atlanta History Museum, now features Migos. History museums aren’t usually in the habit of a large curved expanse of structural glass and limestone referencing rap songs, but the Atlanta History Center is rising from a base of Georgia granite. The façade opens going through an unprecedented period of reinvention, into an atrium with 30-foot-high ceilings that replaced a clearing cobwebs from its image and projecting the slightly dim and cramped train station-styled lobby. An daring notion that history can be, well, hip. allusion to Atlanta’s railroading-fueled past, that look When the Federal Bar Association holds a reception didn’t fully reflect the city’s more dynamic present, but on the Atlanta History Center’s leafy 33-acre campus the soaring, sunlight-filled new entrance does. And all during its Atlanta Convention on Sept. 14, there will be that curved glass facing West Paces Ferry Road—an other apparent recent changes and evidence of even important stretch that connects the Buck- more afoot. -

Raise the Curtain

JAN-FEB 2016 THEAtlanta OFFICIAL VISITORS GUIDE OF AtLANTA CoNVENTI ON &Now VISITORS BUREAU ATLANTA.NET RAISE THE CURTAIN THE NEW YEAR USHERS IN EXCITING NEW ADDITIONS TO SOME OF AtLANTA’S FAVORITE ATTRACTIONS INCLUDING THE WORLDS OF PUPPETRY MUSEUM AT CENTER FOR PUPPETRY ARTS. B ARGAIN BITES SEE PAGE 24 V ALENTINE’S DAY GIFT GUIDE SEE PAGE 32 SOP RTS CENTRAL SEE PAGE 36 ATLANTA’S MUST-SEA ATTRACTION. In 2015, Georgia Aquarium won the TripAdvisor Travelers’ Choice award as the #1 aquarium in the U.S. Don’t miss this amazing attraction while you’re here in Atlanta. For one low price, you’ll see all the exhibits and shows, and you’ll get a special discount when you book online. Plan your visit today at GeorgiaAquarium.org | 404.581.4000 | Georgia Aquarium is a not-for-profit organization, inspiring awareness and conservation of aquatic animals. F ATLANTA JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016 O CONTENTS en’s museum DR D CHIL ENE OP E Y R NEWL THE 6 CALENDAR 36 SPORTS OF EVENTS SPORTS CENTRAL 14 Our hottest picks for Start the year with NASCAR, January and February’s basketball and more. what’S new events 38 ARC AROUND 11 INSIDER INFO THE PARK AT our Tips, conventions, discounts Centennial Olympic Park on tickets and visitor anchors a walkable ring of ATTRACTIONS information booth locations. some of the city’s best- It’s all here. known attractions. Think you’ve already seen most of the city’s top visitor 12 NEIGHBORHOODS 39 RESOURCE Explore our neighborhoods GUIDE venues? Update your bucket and find the perfect fit for Attractions, restaurants, list with these new and improved your interests, plus special venues, services and events in each ’hood. -

1 Spring 2021 Founded by the Cherokee Garden Club In

GARDEN SPRING 2021 CITINGS FOUNDED BY THE CHEROKEE GARDEN CLUB IN 1975 A LIBRARY OF THE KENAN RESEARCH CENTER AT THE ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 04 THE EARTH IN HER HANDS: 75 EXTRAORDINARY WOMEN WORKING IN THE WORLD OF PLANTS 06 DIRECTOR & EDITOR NEW BOOKS, OLD WISDOM Staci L. Catron ASSOCIATE EDITORS 10 Laura R. Draper Louise S. Gunn Jennie Oldfield SNOWFLAKES IN SPRING FOUNDING PRESIDENT Anne Coppedge Carr 14 (1917–2005) HEAD, HEART, HANDS, HEALTH, AND HISTORY CHAIR Tavia C. McCuean 18 WELCOME INCOMING ADVISORY BOARD MEMBERS ADVISORY BOARD C. Duncan Beard Wright Marshall 22 Helen Mattox Bost Tavia C. McCuean Jeanne Johnson Bowden Raymond McIntyre THE AMERICAN CHESTNUT ORCHARD AT ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER Sharon Jones Cole Ann James Offen Jennifer Cruse-Sanders Caye Johnson Oglesby Elise Blitch Drake Nancy Roberts Patterson Laura Rains Draper Betsy Wilkins Robinson Lee C. Dunn Claire McCants Schwahn 26 Ginger Dixon Fasy T. Blake Segars Kinsey Appleby Harper Melissa Stahel Chris Hastings Martha Tate GIFTS & TRIBUTES TO THE CHEROKEE GARDEN LIBRARY ANNUAL FUND Dale M. Jaeger Yvonne Wade James H. Landon Jane Robinson Whitaker Richard H. Lee Melissa Furniss Wright 34 BOOK, MANUSCRIPT, AND VISUAL ARTS DONATIONS ON COVER Plate 2 from Jane Loudon’s The Ladies’ Flower-Garden of Ornamental Bulbous Plants (London: William Smith, 1841), Cherokee Garden Library Historic Collection. THE EARTH IN HER HANDS: 75 EXTRAORDINARY WOMEN WORKING IN THE WORLD OF PLANTS JENNIFER JEWELL The Earth in Her Hands: 75 Extraordinary CHEROKEE GARDEN LIBRARY UPCOMING Women Working in VIRTUAL TALK WEDNESDAY MAY 12, 2021 the World of Plants 7:00pm Join us on May 12th for a conversation with Jennifer Jewell—host of public radio’s award-winning program and podcast Cultivating Place—as she introduces 75 inspiring women featured in her book, The Earth in Her Hands: 75 Extraordinary Women Working in the World of Plants. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3. -

Artist's Resume

R O B E R T S H E R E R [email protected] www.robertsherer.com ___________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION 1989-92 Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.) degree, Painting. Edinboro University of Pennsylvania, Edinboro, PA. 1987-88 Post-Baccalaureate Independent Study, Advanced Painting, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI. 1982-86 Bachelor of Fine Arts (B.F.A.) degree, Drawing and Painting, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA. 1979-80 Foundation Studies Program, Visual Art, Atlanta College of Art, Atlanta, GA. 1976-78 Arts and Science (A.S.) degree, Visual Art, Walker College, Jasper, AL. SELECTED EXHIBITIONS 2014 - Art, AIDS, America, Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA. (invitational) 2013 - Head, Shoulders, Genes, and Toes, FSU Museum of Fine Arts, Tallahassee, FL. (invitational) 2012 - Permanent Collection, Davis Lisboa Museum of Contemporary Art, Barcelona, Spain. (collection) - Robert Sherer: American Pyrography, Lyman-Eyer Gallery, Provincetown, MA. (solo) - 30x30 No. 10, Gruppenaustellung, Galerie Kunstbehandlung. KG, Munich, Germany. (group) - Centennial Ball Auction, Alliance Française d'Atlanta, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - 17th Annual Hambidge Center Gala, Goat Farm Art Center, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - Summer Group Show, Lyman-Eyer Gallery, Provincetown, MA. (group) - Evening for Equality, Equality Foundation of Georgia, Twelve Hotel, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - Selected Blood Works: Robert Sherer, Lyman-Eyer Gallery, Provincetown, MA. (solo) - Faculty Exhibition, Fine Arts Gallery, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA. (group) - Art Papers Auction, Mason Murer Gallery, Atlanta, GA. (invitational) - 30x30 No.10, Gruppenaustellung, Galerie Kunstbehandlung. KG, Munich, Germany. (group) - Hidden and Forbidden Identities, ArtExpo International, Palazzo Albrizzi, Venice, Italy (juried) - Georgia Lawyers for the Arts - 35th Annual Gala, King Plow Art Center, Atlanta, (invitational) - Gallery Artists, Galerie Kunstbehandlung.