Party-Political Responses to the Alternative for Germany in Comparative Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Joint Committee on the Handling of Security-Relevant Research Publishing Information

October 2016 | Progress Report Joint Committee on the Handling of Security-Relevant Research Publishing information Published by Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher Leopoldina e. V. President: Prof. Jörg Hacker – German National Academy of Sciences – Jägerberg 1, 06108 Halle (Saale), Germany Editor Dr Johannes Fritsch, Yvonne Borchert German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina Contact Office of the Joint Committee on the Handling of Security-Relevant Research German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina Head: Dr Johannes Fritsch Reinhardtstraße 14, 10117 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49 (0)30 2038 997-420 [email protected] www.leopoldina.org/de/ausschuss-dual-use Contact at the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) Dr Ingrid Ohlert German Research Foundation Kennedyallee 40, 53175 Bonn, Germany Tel.: +49 (0)228 885-2258 [email protected] www.dfg.de Design and setting unicom Werbeagentur GmbH, Berlin Recommended form of citation German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) (2016): “Joint Committee on the Handling of Security- Relevant Research”, progress report of 1 October 2016, Halle (Saale), 22 pages Joint Committee on the Handling of Security-Relevant Research Preface 3 Preface This progress report begins with a summary in Chapter A of the developments leading up to the establishment of the Joint Committee on the Handling of Security-Relevant Research by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Founda- tion) and the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in November 2014. Chapter B reports on the tasks of the Joint Committee and its activities up to 1 Octo- ber 2016, with particular focus on the progress of implementing the DFG and the Leo- poldina’s “Recommendations for Handling Security-Relevant Research” of June 2014. -

Framing Through Names and Titles in German

Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2020), pages 4924–4932 Marseille, 11–16 May 2020 c European Language Resources Association (ELRA), licensed under CC-BY-NC Doctor Who? Framing Through Names and Titles in German Esther van den Berg∗z, Katharina Korfhagey, Josef Ruppenhofer∗z, Michael Wiegand∗ and Katja Markert∗y ∗Leibniz ScienceCampus, Heidelberg/Mannheim, Germany yInstitute of Computational Linguistics, Heidelberg University, Germany zInstitute for German Language, Mannheim, Germany fvdberg|korfhage|[email protected] fruppenhofer|[email protected] Abstract Entity framing is the selection of aspects of an entity to promote a particular viewpoint towards that entity. We investigate entity framing of political figures through the use of names and titles in German online discourse, enhancing current research in entity framing through titling and naming that concentrates on English only. We collect tweets that mention prominent German politicians and annotate them for stance. We find that the formality of naming in these tweets correlates positively with their stance. This confirms sociolinguistic observations that naming and titling can have a status-indicating function and suggests that this function is dominant in German tweets mentioning political figures. We also find that this status-indicating function is much weaker in tweets from users that are politically left-leaning than in tweets by right-leaning users. This is in line with observations from moral psychology that left-leaning and right-leaning users assign different importance to maintaining social hierarchies. Keywords: framing, naming, Twitter, German, stance, sentiment, social media 1. Introduction An interesting language to contrast with English in terms of naming and titling is German. -

Parlamentsmaterialien Beim DIP (PDF, 38KB

DIP21 Extrakt Deutscher Bundestag Diese Seite ist ein Auszug aus DIP, dem Dokumentations- und Informationssystem für Parlamentarische Vorgänge , das vom Deutschen Bundestag und vom Bundesrat gemeinsam betrieben wird. Mit DIP können Sie umfassende Recherchen zu den parlamentarischen Beratungen in beiden Häusern durchführen (ggf. oben klicken). Basisinformationen über den Vorgang [ID: 17-47093] 17. Wahlperiode Vorgangstyp: Gesetzgebung ... Gesetz zur Änderung des Urheberrechtsgesetzes Initiative: Bundesregierung Aktueller Stand: Verkündet Archivsignatur: XVII/424 GESTA-Ordnungsnummer: C132 Zustimmungsbedürftigkeit: Nein , laut Gesetzentwurf (Drs 514/12) Nein , laut Verkündung (BGBl I) Wichtige Drucksachen: BR-Drs 514/12 (Gesetzentwurf) BT-Drs 17/11470 (Gesetzentwurf) BT-Drs 17/12534 (Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht) Plenum: 1. Durchgang: BR-PlPr 901 , S. 448B - 448C 1. Beratung: BT-PlPr 17/211 , S. 25799A - 25809C 2. Beratung: BT-PlPr 17/226 , S. 28222B - 28237C 3. Beratung: BT-PlPr 17/226 , S. 28237B 2. Durchgang: BR-PlPr 908 , S. 160C - 160D Verkündung: Gesetz vom 07.05.2013 - Bundesgesetzblatt Teil I 2013 Nr. 23 14.05.2013 S. 1161 Titel bei Verkündung: Achtes Gesetz zur Änderung des Urheberrechtsgesetzes Inkrafttreten: 01.08.2013 Sachgebiete: Recht ; Medien, Kommunikation und Informationstechnik Inhalt Einführung eines sog. Leistungsschutzrechtes für Presseverlage zur Verbesserung des Schutzes von Presseerzeugnissen im Internet: ausschließliches Recht zur gewerblichen öffentlichen Zugänglichmachung als Schutz vor Suchmaschinen und vergleichbaren -

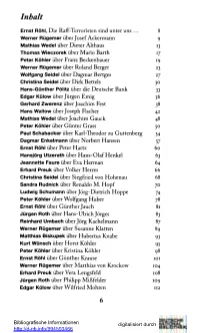

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen Sind Unter Uns

Inhalt Ernst Röhl, Die Raff-Terroristen sind unter uns ... 8 Werner Rügemer über Josef Ackermann 9 Mathias Wedel über Dieter Althaus 13 Thomas Wieczorek über Mario Barth 17 Peter Köhler über Franz Beckenbauer 19 Werner Rügemer über Roland Berger 23 Wolfgang Seidel über Dagmar Bertges 27 Christina Seidel über Dirk Bettels 30 Hans-Günther Pölitz über die Deutsche Bank 33 Edgar Külow über Jürgen Emig 36 Gerhard Zwerenz über Joachim Fest 38 Hans Wallow über Joseph Fischer 42 Mathias Wedel über Joachim Gauck 48 Peter Köhler über Günter Grass 50 Paul Schabacker über Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg 54 Dagmar Enkelmann über Norbert Hansen 57 Ernst Röhl über Peter Hartz 60 Hansjörg Utzerath über Hans-Olaf Henkel 63 Jeannette Faure über Eva Herman 64 Erhard Preuk über Volker Herres 66 Christina Seidel über Siegfried von Hohenau 68 Sandra Rudnick über Renaldo M. Hopf 70 Ludwig Schumann über Jörg-Dietrich Hoppe 74 Peter Köhler über Wolfgang Huber 78 Ernst Röhl über Günther Jauch 81 Jürgen Roth über Hans-Ulrich Jorges 83 Reinhard Limbach über Jörg Kachelmann 87 Werner Rügemer über Susanne Klatten 89 Matthias Biskupek über Hubertus Knabe 93 Kurt Wünsch über Horst Köhler 95 Peter Köhler über Kristina Köhler 98 Ernst Röhl über Günther Krause 101 Werner Rügemer über Matthias von Krockow 104 Erhard Preuk über Vera Lengsfeld 108 Jürgen Roth über Philipp Mißfelder 109 Edgar Külow über Wilfried Mohren 112 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/994503466 Paul Schabacker über Franz Müntefering 115 Christoph Hofrichter über Günther Oettinger 120 Reinhard Limbach über Hubertus Pellengahr 122 Stephan Krull über Ferdinand Piëch 123 Ernst Röhl über Heinrich von Pierer 127 Paul Schabacker über Papst Benedikt XVI. -

Germany 2018 International Religious Freedom Report

GERMANY 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution prohibits religious discrimination and provides for freedom of faith and conscience and the practice of one’s religion. The country’s 16 states exercise considerable autonomy on registration of religious groups and other matters. Unrecognized religious groups are ineligible for tax benefits. The federal and some state offices of the domestic intelligence service continued to monitor the activities of certain Muslim groups. Authorities also monitored the Church of Scientology (COS), which reported continued government discrimination against its members. Certain states continued to ban or restrict the use of religious clothing or symbols, including headscarves, for some state employees, particularly teachers and courtroom officials. While senior government leaders continued to condemn anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim sentiment, some members of the federal parliament and state assemblies from the Alternative for Germany (AfD) Party again made anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim statements. The federal and seven state governments appointed anti-Semitism commissioners for the first time, following a recommendation in a parliament-commissioned 2017 experts’ report to create a federal anti-Semitism commissioner in response to growing anti-Semitism. The federal anti-Semitism commissioner serves as a contact for Jewish groups and coordinates initiatives to combat anti-Semitism in the federal ministries. In July the government announced it would increase social welfare funding for Holocaust survivors by 75 million euros ($86 million) in 2019. In March Federal Interior Minister Horst Seehofer said he did not consider Islam to be a part of the country’s culture, and that the country was characterized by Christianity. -

Jahresbericht 2020

BaFin Jahresbericht der Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht 2020 Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht der Bundesanstaltfür Jahresbericht 2020 © Pixabay/antelope-canyon iStock-996573506_ooddysmile Jahresbericht 2020 der Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort 11 Die BaFin in Kürze 12 Die BaFin als integrierte Aufsicht und Nationale Abwicklungsbehörde 13 1 Aufgaben 13 2 Ein Blick auf die zentralen Aufgaben 14 2.1 Die Bankenaufsicht 14 2.2 Die Versicherungsaufsicht 15 2.3 Die Wertpapieraufsicht 15 2.4 Kollektiver Verbraucherschutz 15 2.5 Gegen Geldwäsche und unerlaubte Geschäfte 16 2.6 Abwicklung 16 2.7 Die BaFin international 17 2.8 Innere Verwaltung und Recht 17 Zahlen im Überblick 18 I. Schlaglichter 22 1 COVID-19 23 1.1 BaFin passt Rahmenbedingungen in der Krise an 23 1.1.1 Bankenaufsicht 23 1.1.2 Versicherungs- und Pensionsfondsaufsicht 25 1.1.3 Wertpapieraufsicht 26 1.1.4 Geldwäschebekämpfung 27 1.1.5 Erlaubnispflicht 27 2 Wirecard 27 3 Brexit 29 4 Digitalisierung 30 5 Sustainable Finance 32 6 Niedrigzinsumfeld 32 6.1 Lage der Kreditinstitute 32 6.2 Lage der Versicherer und Pensionskassen 32 7 Geldwäscheprävention 33 8 Solvency-II-Review 34 9 Bessere Liquiditätssteuerung bei offenen Investmentvermögen 35 II. Die BaFin international 40 1 Deutsche EU-Ratspräsidentschaft 41 1.1 MiCA – Märkte für Kryptowerte 41 1.2 DORA – Digitale operationelle Resilienz des Finanzsektors 42 1.3 Europäische Kapitalmarktunion 42 2 Bilaterale und multilaterale Zusammenarbeit 43 3 Arbeiten der drei ESAs 46 3.1 EBA 46 3.2 EIOPA 46 3.3 ESMA 47 3.4 Nachhaltigkeitsbezogene Offenlegungspflichten 47 4 Arbeiten der globalen Standardsetzer 48 4.1 Basler Ausschuss zieht Schlussstrich 48 4.2 IAIS setzt neue Rahmenwerke um 48 4.3 IOSCO im Pandemiejahr 49 4.4 FSB untersuchte Folgen der Corona-Pandemie 49 III. -

Germany: Baffled Hegemon Constanze Stelzenmüller

POLICY BRIEF Germany: Baffled hegemon Constanze Stelzenmüller Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany has transformed into a hegemonic power in Europe, but recent global upheaval will test the country’s leadership and the strength of its democracy. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY are challenging Europe’s cohesion aggressively, as does the Trump administration’s “America First” The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 turned reunified policy. The impact of this on Germany is stark. No Germany into Europe’s hegemon. But with signs of country in Europe is affected so dramatically by this a major global downturn on the horizon, Germany new systemic competition. Far from being a “shaper again finds itself at the fulcrum of great power nation,” Germany risks being shaped: by events, competition and ideological struggle in Europe. And competitors, challengers, and adversaries. German democracy is being challenged as never before, by internal and external adversaries. Germany’s options are limited. It needs to preserve Europe’s vulnerable ecosystem in its own The greatest political challenge to liberal democracy enlightened self-interest. It will have to compromise within Germany today is the Alternative für on some issues (defense expenditures, trade Deutschland (Alternative for Germany, or AfD), the surpluses, energy policy). But it will also have to first far-right party in the country’s postwar history push back against Russian or Chinese interference, to be represented in all states and in the federal and make common cause with fellow liberal legislature. While it polls nationally at 12 percent, its democracies. With regard to Trump’s America, disruptive impact has been real. -

Motion: Europe Is Worth It – for a Green Recovery Rooted in Solidarity and A

German Bundestag Printed paper 19/20564 19th electoral term 30 June 2020 version Preliminary Motion tabled by the Members of the Bundestag Agnieszka Brugger, Anja Hajduk, Dr Franziska Brantner, Sven-Christian Kindler, Dr Frithjof Schmidt, Margarete Bause, Kai Gehring, Uwe Kekeritz, Katja Keul, Dr Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth, Manuel Sarrazin, Jürgen Trittin, Ottmar von Holtz, Luise Amtsberg, Lisa Badum, Danyal Bayaz, Ekin Deligöz, Katja Dörner, Katharina Dröge, Britta Haßelmann, Steffi Lemke, Claudia Müller, Beate Müller-Gemmeke, Erhard Grundl, Dr Kirsten Kappert-Gonther, Maria Klein-Schmeink, Christian Kühn, Stephan Kühn, Stefan Schmidt, Dr Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn, Markus Tressel, Lisa Paus, Tabea Rößner, Corinna Rüffer, Margit Stumpp, Dr Konstantin von Notz, Dr Julia Verlinden, Beate Walter-Rosenheimer, Gerhard Zickenheiner and the Alliance 90/The Greens parliamentary group be to Europe is worth it – for a green recovery rooted in solidarity and a strong 2021- 2027 EU budget the by replaced The Bundestag is requested to adopt the following resolution: I. The German Bundestag notes: A strong European Union (EU) built on solidarity which protects its citizens and our livelihoods is the best investment we can make in our future. Our aim is an EU that also and especially proves its worth during these difficult times of the corona pandemic, that fosters democracy, prosperity, equality and health and that resolutely tackles the challenge of the century that is climate protection. We need an EU that bolsters international cooperation on the world stage and does not abandon the weakest on this earth. proofread This requires an EU capable of taking effective action both internally and externally, it requires greater solidarity on our continent and beyond - because no country can effectively combat the climate crisis on its own, no country can stamp out the pandemic on its own. -

![Detering | Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? [Was Bedeutet Das Alles?] Heinrich Detering Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? Zur Rhetorik Der Parlamentarischen Rechten](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3046/detering-was-hei%C3%9Ft-hier-%C2%BBwir%C2%AB-was-bedeutet-das-alles-heinrich-detering-was-hei%C3%9Ft-hier-%C2%BBwir%C2%AB-zur-rhetorik-der-parlamentarischen-rechten-173046.webp)

Detering | Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? [Was Bedeutet Das Alles?] Heinrich Detering Was Heißt Hier »Wir«? Zur Rhetorik Der Parlamentarischen Rechten

Detering | Was heißt hier »wir«? [Was bedeutet das alles?] Heinrich Detering Was heißt hier »wir«? Zur Rhetorik der parlamentarischen Rechten Reclam Reclams UniveRsal-BiBliothek Nr. 19619 2019 Philipp Reclam jun. Verlag GmbH, Siemensstraße 32, 71254 Ditzingen Gestaltung: Cornelia Feyll, Friedrich Forssman Druck und Bindung: Kösel GmbH & Co. KG, Am Buchweg 1, 87452 Altusried-Krugzell Printed in Germany 2019 Reclam, UniveRsal-BiBliothek und Reclams UniveRsal-BiBliothek sind eingetragene Marken der Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart ISBn 978-3-15-019619-9 Auch als E-Book erhältlich www.reclam.de Inhalt Reizwörter und Leseweisen 7 Wir oder die Barbarei 10 Das System der Zweideutigkeit 15 Unser Deutschland, unsere Vernichtung, unsere Rache 21 Ich und meine Gemeinschaft 30 Tausend Jahre, zwölf Jahre 34 Unsere Sprache, unsere Kultur 40 Anmerkungen 50 Nachbemerkung 53 Leseempfehlungen 58 Über den Autor 60 »Sie haben die unglaubwürdige Kühnheit, sich mit Deutschland zu verwechseln! Wo doch vielleicht der Augenblick nicht fern ist, da dem deutschen Volke das Letzte daran gelegen sein wird, nicht mit ihnen verwechselt zu werden.« Thomas Mann, Ein Briefwechsel (1936) Reizwörter und Leseweisen Die Hitlerzeit – ein »Vogelschiss«; die in Hamburg gebo- rene SPD-Politikerin Aydan Özoğuz – ein Fall, der »in Ana- tolien entsorgt« werden sollte; muslimische Flüchtlinge – »Kopftuchmädchen und Messermänner«: Formulierungen wie diese haben in den letzten Jahren und Monaten im- mer von neuem für öffentliche Empörung, für Gegenreden und Richtigstellungen -

Dr. Peter Gauweiler (CDU/CSU)

Inhaltsverzeichnis Plenarprotokoll 18/9 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 9. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 17. Januar 2014 Inhalt: Tagesordnungspunkt 15: Tagesordnungspunkt 16: Vereinbarte Debatte: zum Arbeitsprogramm Antrag der Abgeordneten Ulla Jelpke, Jan der Europäischen Kommission . 503 B Korte, Katrin Kunert, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Das Massen- Axel Schäfer (Bochum) (SPD) . 503 B sterben an den EU-Außengrenzen been- Alexander Ulrich (DIE LINKE) . 505 A den – Für eine offene, solidarische und hu- mane Flüchtlingspolitik der Europäischen Gunther Krichbaum (CDU/CSU) . 506 C Union Drucksache 18/288 . 524 D Manuel Sarrazin (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 508 C Ulla Jelpke (DIE LINKE) . 525 A Michael Roth, Staatsminister Charles M. Huber (CDU/CSU) . 525 D AA . 510 A Thomas Silberhorn (CDU/CSU) . 528 A Britta Haßelmann (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 510 C Luise Amtsberg (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 530 A Andrej Hunko (DIE LINKE) . 511 D Christina Kampmann (SPD) . 532 A Manuel Sarrazin (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 512 B Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) . 533 D Detlef Seif (CDU/CSU) . 513 A Stephan Mayer (Altötting) (CDU/CSU) . 534 D Dr. Diether Dehm (DIE LINKE) . 513 C Volker Beck (Köln) (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 535 C Annalena Baerbock (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 514 D Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) . 536 A Annalena Baerbock (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 515 D Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) . 536 D Dagmar Schmidt (Wetzlar) (SPD) . 517 B Tom Koenigs (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . 538 A Jürgen Hardt (CDU/CSU) . 518 C Sabine Bätzing-Lichtenthäler (SPD) . 539 A Norbert Spinrath (SPD) . 520 C Marian Wendt (CDU/CSU) . 540 C Dr. Peter Gauweiler (CDU/CSU) . -

Politische Jugendstudie Von BRAVO Und Yougov

Politische Jugendstudie von BRAVO und YouGov © 2017 YouGov Deutschland GmbH Veröffentlichungen - auch auszugsweise - bedürfen der schriftlichen Zustimmung durch die Bauer Media Group und die YouGov Deutschland GmbH. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Zusammenfassung 2. Ergebnisse 3. Untersuchungsdesign 4. Über YouGov und Bauer Media Group © YouGov 2017 – Politische Jugendstudie von Bravo und YouGov 2 Zusammenfassung 3 Zusammenfassung I Politisches Interesse § Das politische Interesse bei den jugendlichen Deutschen zwischen 14 und 17 Jahren fällt sehr gemischt aus (ca. 1/3 stark interessiert, 1/3 mittelmäßig und 1/3 kaum interessiert). Das Vorurteil über eine politisch desinteressierte Jugend lässt sich nicht bestätigen. § Kontaktpunkte zu politischen Themen haben die Jugendlichen vor allem in der Schule (75 Prozent). An zweiter Stelle steht die Familie (57 Prozent), gefolgt von den Freunden (47 Prozent). Vor allem die politisch stark Interessierten diskutieren politische Themen auch im Internet (17 Prozent Gesamt). § Nur ein gutes Drittel beschäftigt sich intensiv und regelmäßig mit politischen Themen . Bei ähnlich vielen spielt Politik im eigenem Umfeld keine große Rolle. Dennoch erkennt der Großteil der Jugendlichen (80 Prozent) die Bedeutung von Wahlen, um die eigenen Interessen vertreten zu lassen. Eine Mehrheit (65 Prozent) wünscht sich ebenfalls mehr politisches Engagement der Menschen. Bei Jungen zeigt sich dabei eine stärkere Beschäftigung mit dem Thema Politik als bei Mädchen. Informationsverhalten § Ihrem Alter entsprechend informieren sich die Jugendlichen am häufigsten im Schulunterricht über politische Themen (51 Prozent „sehr häufig“ oder „häufig“) . An zweiter Stelle steht das Fernsehen (48 Prozent), gefolgt von Gesprächen mit Familie, Bekannten oder Freunden (43 Prozent). Mit News-Apps und sozialen Netzwerken folgen danach digitale Kanäle. Print-Ausgaben von Zeitungen und Zeitschriften spielen dagegen nur eine kleinere Rolle.