Expression of the PPM1F Gene Is Regulated by Stress and Associated with Anxiety and Depression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Profiling Data

Compound Name DiscoveRx Gene Symbol Entrez Gene Percent Compound Symbol Control Concentration (nM) JNK-IN-8 AAK1 AAK1 69 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(E255K)-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317I)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 87 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317I)-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317L)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 65 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(F317L)-phosphorylated ABL1 61 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(H396P)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 42 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(H396P)-phosphorylated ABL1 60 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(M351T)-phosphorylated ABL1 81 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Q252H)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Q252H)-phosphorylated ABL1 56 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(T315I)-nonphosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(T315I)-phosphorylated ABL1 92 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1(Y253F)-phosphorylated ABL1 71 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1-nonphosphorylated ABL1 97 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL1-phosphorylated ABL1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ABL2 ABL2 97 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR1 ACVR1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR1B ACVR1B 88 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR2A ACVR2A 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVR2B ACVR2B 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ACVRL1 ACVRL1 96 1000 JNK-IN-8 ADCK3 CABC1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ADCK4 ADCK4 93 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT1 AKT1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT2 AKT2 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AKT3 AKT3 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ALK ALK 85 1000 JNK-IN-8 AMPK-alpha1 PRKAA1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AMPK-alpha2 PRKAA2 84 1000 JNK-IN-8 ANKK1 ANKK1 75 1000 JNK-IN-8 ARK5 NUAK1 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ASK1 MAP3K5 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 ASK2 MAP3K6 93 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKA AURKA 100 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKA AURKA 84 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKB AURKB 83 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKB AURKB 96 1000 JNK-IN-8 AURKC AURKC 95 1000 JNK-IN-8 -

Gene Expression Profiling of Micrornas Associated with UCA1 in Bladder Cancer Cells

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY 48: 1617-1627, 2016 Gene expression profiling of microRNAs associated with UCA1 in bladder cancer cells XIAOJUAN XIE1,2, JINGJING PAN1, LIQIANG WEI2, SHOUZHEN WU3, HUILIAN HOU4, XU LI3 and WEI CHEN1 1Department of Clinical Laboratory, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061; 2Shaanxi Center for Clinical Laboratory, Shaanxi Provincial People's Hospital, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710068; 3Center for Translational Medicine, 4Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061, P.R. China Received November 11, 2015; Accepted December 27, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3357 Abstract. Emerging evidence indicates that non-coding and positively correlated with miR-196a, whereas UCA1 and RNAs, such as lncRNAs and microRNAs, play important miR-196a were negatively correlated with p27kip1, which was roles in diverse diseases, such as cancer, immune diseases downregulated in bladder cancer patients. Thus, our findings and cardiovascular diseases. Interestingly, lncRNAs could provided valuable information on miRNAs associated with directly or indirectly regulate the expression of miRNAs. UCA1 in bladder cancer, which could be helpful to further However, the expression profiling of miRNAs associated with explore the related genes and molecular networks fundamental UCA1 in bladder cancer remains unknown. Here, we used in bladder cancer progression. Illumina deep sequencing to sequence miRNA libraries from both the UCA1 knockdown and normal high-expression 5637 Introduction cells. We identified 225 and 235 miRNAs expressed in 5637 cells of normal high-expression and knockdown of UCA1, Recently, emerging studies have demonstrated that 70-90% of respectively. -

New Insights in RBM20 Cardiomyopathy

Current Heart Failure Reports (2020) 17:234–246 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-020-00475-x TRANSLATIONAL RESEARCH IN HEART FAILURE (J BACKS & M VAN DEN HOOGENHOF, SECTION EDITORS) New Insights in RBM20 Cardiomyopathy D. Lennermann1,2 & J. Backs1,2 & M. M. G. van den Hoogenhof1,2 Published online: 13 August 2020 # The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Purpose of Review This review aims to give an update on recent findings related to the cardiac splicing factor RNA-binding motif protein 20 (RBM20) and RBM20 cardiomyopathy, a form of dilated cardiomyopathy caused by mutations in RBM20. Recent Findings While most research on RBM20 splicing targets has focused on titin (TTN), multiple studies over the last years have shown that other splicing targets of RBM20 including Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase IIδ (CAMK2D) might be critically involved in the development of RBM20 cardiomyopathy. In this regard, loss of RBM20 causes an abnormal intracellular calcium handling, which may relate to the arrhythmogenic presentation of RBM20 cardiomyopathy. In addition, RBM20 presents clinically in a highly gender-specific manner, with male patients suffering from an earlier disease onset and a more severe disease progression. Summary Further research on RBM20, and treatment of RBM20 cardiomyopathy, will need to consider both the multitude and relative contribution of the different splicing targets and related pathways, as well as gender differences. Keywords RBM20 . Dilated cardiomyopathy . CaMKIIδ . Calcium handling . Gender differences . Titin Introduction (ARVC), where a small number of genes account for most of the genetic causes, DCM-causing mutations have been ob- Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), as defined by left ventricular served in a variety of genes of diverse ontology [2]. -

Supplementary Table 9. Functional Annotation Clustering Results for the Union (GS3) of the Top Genes from the SNP-Level and Gene-Based Analyses (See ST4)

Supplementary Table 9. Functional Annotation Clustering Results for the union (GS3) of the top genes from the SNP-level and Gene-based analyses (see ST4) Column Header Key Annotation Cluster Name of cluster, sorted by descending Enrichment score Enrichment Score EASE enrichment score for functional annotation cluster Category Pathway Database Term Pathway name/Identifier Count Number of genes in the submitted list in the specified term % Percentage of identified genes in the submitted list associated with the specified term PValue Significance level associated with the EASE enrichment score for the term Genes List of genes present in the term List Total Number of genes from the submitted list present in the category Pop Hits Number of genes involved in the specified term (category-specific) Pop Total Number of genes in the human genome background (category-specific) Fold Enrichment Ratio of the proportion of count to list total and population hits to population total Bonferroni Bonferroni adjustment of p-value Benjamini Benjamini adjustment of p-value FDR False Discovery Rate of p-value (percent form) Annotation Cluster 1 Enrichment Score: 3.8978262119731335 Category Term Count % PValue Genes List Total Pop Hits Pop Total Fold Enrichment Bonferroni Benjamini FDR GOTERM_CC_DIRECT GO:0005886~plasma membrane 383 24.33290978 5.74E-05 SLC9A9, XRCC5, HRAS, CHMP3, ATP1B2, EFNA1, OSMR, SLC9A3, EFNA3, UTRN, SYT6, ZNRF2, APP, AT1425 4121 18224 1.18857065 0.038655922 0.038655922 0.086284383 UP_KEYWORDS Membrane 626 39.77128335 1.53E-04 SLC9A9, HRAS, -

Characterization of the Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitor SU11248 (Sunitinib/ SUTENT in Vitro and in Vivo

TECHNISCHE UNIVERSITÄT MÜNCHEN Lehrstuhl für Genetik Characterization of the Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitor SU11248 (Sunitinib/ SUTENT in vitro and in vivo - Towards Response Prediction in Cancer Therapy with Kinase Inhibitors Michaela Bairlein Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ. -Prof. Dr. K. Schneitz Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. Univ.-Prof. Dr. A. Gierl 2. Hon.-Prof. Dr. h.c. A. Ullrich (Eberhard-Karls-Universität Tübingen) 3. Univ.-Prof. A. Schnieke, Ph.D. Die Dissertation wurde am 07.01.2010 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät Wissenschaftszentrum Weihenstephan für Ernährung, Landnutzung und Umwelt am 19.04.2010 angenommen. FOR MY PARENTS 1 Contents 2 Summary ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 3 Zusammenfassung .................................................................................................................................................... 6 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 4.1 Cancer .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Activation of Diverse Signalling Pathways by Oncogenic PIK3CA Mutations

ARTICLE Received 14 Feb 2014 | Accepted 12 Aug 2014 | Published 23 Sep 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5961 Activation of diverse signalling pathways by oncogenic PIK3CA mutations Xinyan Wu1, Santosh Renuse2,3, Nandini A. Sahasrabuddhe2,4, Muhammad Saddiq Zahari1, Raghothama Chaerkady1, Min-Sik Kim1, Raja S. Nirujogi2, Morassa Mohseni1, Praveen Kumar2,4, Rajesh Raju2, Jun Zhong1, Jian Yang5, Johnathan Neiswinger6, Jun-Seop Jeong6, Robert Newman6, Maureen A. Powers7, Babu Lal Somani2, Edward Gabrielson8, Saraswati Sukumar9, Vered Stearns9, Jiang Qian10, Heng Zhu6, Bert Vogelstein5, Ben Ho Park9 & Akhilesh Pandey1,8,9 The PIK3CA gene is frequently mutated in human cancers. Here we carry out a SILAC-based quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis using isogenic knockin cell lines containing ‘driver’ oncogenic mutations of PIK3CA to dissect the signalling mechanisms responsible for oncogenic phenotypes induced by mutant PIK3CA. From 8,075 unique phosphopeptides identified, we observe that aberrant activation of PI3K pathway leads to increased phosphorylation of a surprisingly wide variety of kinases and downstream signalling networks. Here, by integrating phosphoproteomic data with human protein microarray-based AKT1 kinase assays, we discover and validate six novel AKT1 substrates, including cortactin. Through mutagenesis studies, we demonstrate that phosphorylation of cortactin by AKT1 is important for mutant PI3K-enhanced cell migration and invasion. Our study describes a quantitative and global approach for identifying mutation-specific signalling events and for discovering novel signalling molecules as readouts of pathway activation or potential therapeutic targets. 1 McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine and Department of Biological Chemistry, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, 733 North Broadway, BRB 527, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA. -

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain -

Clinical, Molecular, and Immune Analysis of Dabrafenib-Trametinib

Supplementary Online Content Chen G, McQuade JL, Panka DJ, et al. Clinical, molecular and immune analysis of dabrafenib-trametinib combination treatment for metastatic melanoma that progressed during BRAF inhibitor monotherapy: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. Published online April 28, 2016. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0509. eMethods. eReferences. eTable 1. Clinical efficacy eTable 2. Adverse events eTable 3. Correlation of baseline patient characteristics with treatment outcomes eTable 4. Patient responses and baseline IHC results eFigure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival eFigure 2. Correlation between IHC and RNAseq results eFigure 3. pPRAS40 expression and PFS eFigure 4. Baseline and treatment-induced changes in immune infiltrates eFigure 5. PD-L1 expression eTable 5. Nonsynonymous mutations detected by WES in baseline tumors This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2016 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/30/2021 eMethods Whole exome sequencing Whole exome capture libraries for both tumor and normal samples were constructed using 100ng genomic DNA input and following the protocol as described by Fisher et al.,3 with the following adapter modification: Illumina paired end adapters were replaced with palindromic forked adapters with unique 8 base index sequences embedded within the adapter. In-solution hybrid selection was performed using the Illumina Rapid Capture Exome enrichment kit with 38Mb target territory (29Mb baited). The targeted region includes 98.3% of the intervals in the Refseq exome database. Dual-indexed libraries were pooled into groups of up to 96 samples prior to hybridization. -

In KRAS-Mutated Colorectal Cancer

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 5, 2010; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0376 AuthorPublished manuscripts OnlineFirst have been peeron Octoberreviewed and 5, 2010accepted as for10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0376 publication but have not yet been edited. Identification of Predictive Markers of Response to the MEK1/2 Inhibitor Selumetinib (AZD6244) in KRAS-Mutated Colorectal Cancer John J. Tentler1, Sujatha Nallapareddy1, Aik Choon Tan1, Anna Spreafico1, Todd M. Pitts1, M. Pia Morelli1, Heather M. Selby1, Maria I. Kachaeva1, Sara A. Flanigan1, Gillian N. Kulikowski1, Stephen Leong1 John J. Arcaroli1, Wells A. Messersmith1 and S. Gail Eckhardt1 Author Affilliations: Division of Medical Oncology1, University of Colorado Denver Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colorado Running Title: Predictive Biomarkers for Selumetinib in CRC Key Words: MEK inhibitors, predictive biomarkers, colorectal cancer Abbreviations: CRC: colorectal cancer; MAPK: mitogen activated protein kinase; MEK: MAPK/ERK kinase; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; FZD2: frizzled homolog 2 Financial Support: Research grants CA106349 (SGE); CA079446 (SGE), CA46934 (NCI Cancer Center Support Grant); AstraZeneca Inc. Research Agreement (AS, SGE); Cancer League of Colorado Seed Grant (JJT). Requests for reprints: John J. Tentler, Ph.D. 12801 E 17th Ave, MS 8117, Aurora, CO 80045. email: [email protected]; 1 1 Potential Conflicts of Interest: Research funding provided by AstraZeneca to AS, SGE. Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Copyright © 2010 American Association for Cancer Research 1 Downloaded from mct.aacrjournals.org on September 30, 2021. © 2010 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on October 5, 2010; DOI: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0376 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. -

Targeted MS Quantitation Assays for Signal Transduction Protein Pathways

Targeted MS quantitation assays for signal transduction protein pathways Paul Haney R&D Platform Manager Thermo Scientific Protein Research Products Rockford, IL Why Targeted Quantitative Proteomics via Mass Spec? . Measure protein abundance and protein isoforms (e.g. splice variants, PTMs) without the need for antibodies . Avoid immuno-based cross- reactivity during multiplexing. Validate relative quantitation data from discovery proteomic experiments 2 How Do You Select Peptides for Targeted MS Assays? List of Proteins Spectral library Discovery data repositories In silico prediction Pinpoint 1.2 Hypothesis Experimental List of target peptides and transitions 3 How Do You Select Peptides for Targeted MS Assays? List of Proteins Spectral library Discovery data repositories In silico prediction Pinpoint 1.2 Hypothesis Experimental Validation Assay results List of target peptides and transitions 4 Tools for Target Peptide Identification and Scheduling . Active-site probes for enzyme subclass enrichment . Rapid recombinant heavy protein expression using human cell-free extracts . Peptide retention time calibration mixture for chromatography QC and targeted method 100 80 60 acquisition scheduling Intensity 40 20 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 5 Tools for Target Peptide Identification and Scheduling . Active-site probes for enzyme subclass enrichment . Rapid recombinant heavy protein expression using human cell-free extracts • Stergachis, A. & MacCoss, M. (2011) Nature Methods (submitted) . Peptide retention time calibration mixture for 100 80 chromatography -

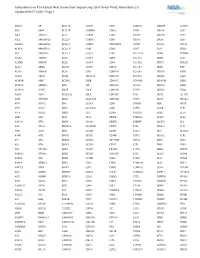

Comprehensive Pan-Cancer Next Generation Sequencing Solid Tumor Panel, Aberration List Updated 08-07-2020 --Page 1

Comprehensive Pan-Cancer Next Generation Sequencing Solid Tumor Panel, Aberration List Updated 08-07-2020 --Page 1 ABCC3 AR BCL11A CANT1 CDK1 CMKLR1 DAB2IP DUSP9 ABI1 ARAF BCL11B CAPRIN1 CDK12 CNBP DACH1 E2F1 ABL1 ARFRP1 BCL2 CAPZB CDK2 CNOT2 DACH2 E2F3 ABL2 ARHGAP20 BCL2A1 CARD11 CDK4 CNTN1 DAXX EBF1 ABLIM1 ARHGAP26 BCL2L1 CARM1 CDK5RAP2 CNTRL DCLK2 ECT2L ACACA ARHGEF12 BCL2L11 CARS CDK6 COG5 DCN EDIL3 ACE ARHGEF7 BCL2L2 CASC5 CDK7 COL11A1 DDB1 EDNRB ACER1 ARID1A BCL3 CASP3 CDK8 COL1A1 DDB2 EED ACSBG1 ARID1B BCL6 CASP7 CDK9 COL1A2 DDIT3 EEFSEC ACSL3 ARID2 BCL7A CASP8 CDKL5 COL3A1 DDR2 EGF ACSL6 ARID5B BCL9 CAV1 CDKN1A COL6A3 DDX10 EGFR ACVR1 ARIH2 BCOR CBFA2T3 CDKN1B COL9A3 DDX20 EGR1 ACVR1B ARNT BCORL1 CBFB CDKN1C COMMD1 DDX39B EGR2 ACVR1C ARRDC4 BCR CBL CDKN2A COX6C DDX3X EGR3 ACVR2A ASMTL BDNF CBLB CDKN2B CPNE1 DDX41 EGR4 ADD3 ASPH BHLHE22 CBLC CDKN2C CPS1 DDX5 EIF1AX ADM ASPSCR1 BICC1 CCDC28A CDKN2D CPSF6 DDX6 EIF4A2 AFF1 ASTN2 BIN1 CCDC6 CDX1 CRADD DEK EIF4E AFF3 ASXL1 BIRC3 CCDC88C CDX2 CREB1 DGKB ELF3 AFF4 ASXL2 BIRC6 CCK CEBPA CREB3L1 DGKI ELF4 AGR3 ATF1 BLM CCL2 CEBPB CREB3L2 DGKZ ELK4 AHCYL1 ATF3 BMP4 CCNA2 CEBPD CREBBP DICER1 ELL AHI1 ATG13 BMPR1A CCNB1IP1 CEBPE CRKL DIRAS3 ELN AHR ATG5 BRAF CCNB3 CENPF CRLF2 DIS3 ELOVL2 AHRR ATIC BRCA1 CCND1 CENPU CRTC1 DIS3L2 ELP2 AIP ATL1 BRCA2 CCND2 CEP170B CRTC3 DKK1 EML1 AK2 ATM BRCC3 CCND3 CEP57 CSF1 DKK2 EML4 AK5 ATP1B4 BRD1 CCNE1 CEP85L CSF1R DKK4 ENPP2 AKAP12 ATP8A2 BRD3 CCNG1 CHCHD7 CSF3 DLEC1 EP300 AKAP6 ATR BRD4 CCT6B CHD2 CSF3R DLL1 EP400 AKAP9 ATRNL1 BRIP1 CD19 CHD4 CSNK1A1 DLL3 -

Brain-Restricted Mtor Inhibition with Binary Pharmacology 2 3 Ziyang Zhang1, Qiwen Fan2,3, Xujun Luo2,3, Kevin J

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.12.336677; this version posted October 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Brain-Restricted mTOR Inhibition with Binary Pharmacology 2 3 Ziyang Zhang1, Qiwen Fan2,3, Xujun Luo2,3, Kevin J. Lou1, William A. Weiss2,3,4,5, Kevan 4 M. Shokat1,* 5 6 1 Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology and Howard Hughes Medical 7 Institute, University of California, San Francisco, California 8 2 Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center, San Francisco, California 9 3 Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, California 10 4 Department of Pediatrics, University of California, San Francisco, California 11 5 Department of Neurological Surgery, University of California, San Francisco, California 12 * Corresponding author. [email protected] (K.M.S.). 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.12.336677; this version posted October 12, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 13 Abstract 14 On-target-off-tissue drug engagement is an important source of adverse effects 15 that constrains the therapeutic window of drug candidates. In diseases of the central 16 nervous system, drugs with brain-restricted pharmacology are highly desirable.