Cattle Rustling and Its Effects Among Three Communities (Dinka, Murle and Nuer) in Jonglei State, South Sudan Phillip T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interaction Between International Aid and South Sudanese

Lost in Translation: The interaction between international humanitarian aid and South Sudanese accountability systems September 2020 This research was conducted by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF) in August and September 2019 and was funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan. The CSRF is implemented by a consortium of the NGOs Saferworld and swisspeace. It is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. This research would not have been possible without the South Sudanese and international aid actors who generously gave their time and insights. It is dedicated to the South Sudanese aid workers who tirelessly balance their personal and professional cultures to deliver assistance to those who need it. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology and limitations ........................................................................................................................... -

The Black Christs of the Black Christs of by J. Penn De

The Black Christs of Africa A Bible of Poems By J. Penn de Ngong Above all, I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. Wilfred Owen, British Poet Poem 22 petition for partition We, the auto-government of the Republic of Ruralia, Voicing the will of the democratic public of Ruralia, Are writing to your Theocratic Union of Urbania. Our grievances are on the following discontentment: Firstly, your purely autocratic Government of Urbania, Has solely dishonoured and condemned the document That we all signed – and codenamed – “Bible of Peace”. You’ve violated its gospel, the cause of our fatal disagreement; Wealth: You’re feeding our autonomous nation with ration apiece. In your annual tour, compare our city – Metropollutant – of Ruralia With its posh sister city of Urbania, proudly dubbed Metropolitania. All our resources, on our watching, are consumed up in Urbania. Our intellectuals and workforce are abundant but redundant. Henceforth, right here, we demarcate to be independent! You are busy strategizing to turn Ruralia into Somalia: Yourselves landlords, creating warlords, tribal militia, And bribing our politicians to speak out your voice, And turning our villages into large ghettos of slum, And our own towns into large cities of Islam. With these experiences, we’ve no choice, But t’ ask, demand, fight... for our voice. They oft’ say the end justifies the means, We, Ruralians, must reform all our ruins; The first option: thru the ballot, Last action: bullet! J. Penn de Ngong (John Ngong Alwong Alith as known in his family) came into this world on a day nobody knows. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Heading with Word in Woodblock

Gambella Region Area Brief Regional Overview Gambella Peoples' region is one of the nine regional states of Ethiopia. This region is located at the western edge of the country bordering South Sudan. The capital of the region, Gambella, is 766km from Addis Ababa. This region has an estimated density of 10 people per square kilometre. The main ethnicities of the region are the Nuer (46.66%), the Anuak 21.16%), Amhara (8.42%), Kafficho (5.04%), Oromo (4.83%), Mezhenger (4%), Shakacho (2.27%), Kambata (1.44%), Tigrean (1.32%) and other ethnic groups predominantly from southern Ethiopia 4.86%. Children below the age of 18 years accounts for 66.5% (27,974) of the refugee population. Female (women and girls) significantly outnumber male (adult & young men) due to the fact that sizable number of adult and young men died during the 21 years of liberation struggle. Currently there are three refugee camps in Gambella region namely Pugnido, Leite Chore and Okugo which host about 68,000 refugees from South Sudan. Pugnido, 876 kilometres from Addis Ababa to the south west is the oldest refugee camp, which is hosting 42,044 refugees and has existed since 1992 while Okugo, which hosts 5,927 refugees, was established in mid 2013 following interethnic clash between Nuer and Murle people. Leite Chore refugee camp, which is under establishment, will host 20,000 South Sudanese asylum seekers displaced from their homeland due to the countrywide deadly armed conflict that erupted in December, 2013 between the supporters of President Salva Kir and the former vice president Dr. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

A Program of USAID/REDSO/ESA Quarterly Report October 1, 2004

A program of USAID/REDSO/ESA Quarterly Report October 1, 2004 – December 31st, 2004 Pact. Cooperative Agreement No. # 623-C-00-02-00101-00 Page 2 of 35 SPF LIST OF ACRONYMS ACAD Abyei Community Action for Development AU-IBAR African Union’s Inter-Africa Bureau for Animal Resources AUNPC All Upper Nile Peace Committee BYDA Bahr el Ghazal Youth Development Agency CA Civil Authorities / Christian Aid CBO Community-Based Organization CRS Catholic Relief Service CSO Civil Society Organization CTO Cognizant Technical Officer DMR Dinka, Misiriyia and Rezeigat DoT Diocese of Torit EDC Education Development Centre EUCO Eastern Upper Nile Consortium FOSCO Federation of Sudanese Civil Society Organization GoS Government of Sudan IAS International Aid Services (formerly International Aid Sweden) IGAD Inter-Governmental Authority on Development KVPPD Kidepo Valley Peace Project and Development NGO Non-Governmental Organization NMPACT Nuba Mountains Plan to Advance Conflict Transformation NRM Natural Resources Management NSCC New Sudan Council of Churches OCA Organizational Capacity Assessment OTI USAID/DCHA’s Office of Transition Initiatives PACTA Project to Advance Conflict Transformation in Abyei PCOS Presbyterian Church of Sudan PDA Pibor Peace and Development Association REDSO/ESA Regional Economic Development Services Office for East and Southern Africa SBeG Southern Bahr el Ghazal SBN Southern Blue Nile SPF Sudan Peace Fund SPLM/A Sudan Peace Liberation Movement/Army SSTI USAID/OTI-funded South Sudan Transition Initiative, implemented by Pact -

Nuer Inter-Communal Conflict and Its Impacts in South Sudan

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-3, Issue-2, 2017 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in The Dinka- Nuer Inter-Communal Conflict and Its Impacts in South Sudan. Wurok Chan Malith Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department Of Sociology, Kariavattom, Campus, University of Kerala. Abstract: Ethnic conflicts become immensely, a and steadfastly, weighed, to be achingly, sparked contentious and controversial conundrum in Africa by an ignominious political rivalry or sturdy vying and in the World, after the end of the Cold War for power and leadership in the country. era. However, the conflict conspicuously encapsulates as an explicit confrontation or Keyword: Ethnicity, Conflict, Natural resources, struggle between groups or individuals over Politics, economic, power, tribal identity, resources and power. Hence the conflict evinces, animosity. attests enormously, a natural process in any community and especially a process of change. 1. Introduction Consequently, the ethnic conflicts are politically floundered and engulfed over economic or political To thoroughly, discuss and belabor the Dinka-Nuer power or over resources such as land and conflict, it necessarily warrants and certainly invaluable minerals. Additionally, internecine precipitates a need to assiduously adumbrate and ethnic conflicts are politically demoed and vouchsafe implicit ideas and the background of the presaged as a slant unequal distribution of Dinka - Nuer lifestyles, their social life, and their resources, the struggle over leadership, inequity, environment. The social structure of Dinka- Nuer, and a vast economic chasm between people, the the traditions, the socio-political system. Moreover, dearth of good governance, management, weak and and the Dinka -Nuer life conflict is normally, unstable regimes and institutions, identity politics characterized by their traditional way of life in their and historical woes and cataclysms. -

Murle History

The History of Murle Migrations The Murle people live in southeastern Sudan and are proud to be Murle. They are proud of their language and customs. They also regard themselves as distinct from the people that live around them. At various times they have been at war with all of the surrounding tribes so they present a united front against what they regard as hostile neighbors. The people call themselves Murle and all other peoples are referred to as moden. The literal translation of this word is “enemy,” although it can also be translated as “strangers.” Even when the Murle are at peace with a given group of neighbors, they still refer to them as moden. The neighboring tribes also return the favor by referring to the Murle as the “enemy.” The Dinka people refer to the Murle as the Beir and the Anuak call them the Ajiba. These were the terms originally used in the early literature to refer to the Murle people. Only after direct contact by the British did their self-name become known and the term Murle is now generally accepted. The Murle are a relatively new ethnic group in Sudan, having immigrated into the region from Ethiopia. The language they speak is from the Surmic language family - languages spoken primarily in southwest Ethiopia. There are three other Surmic speaking people groups presently living in the Sudan: the Didinga, the Longarim and the Tenet. When I asked the Murle elders about their origins they always pointed to the east and said they originated in a place called Jen. -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

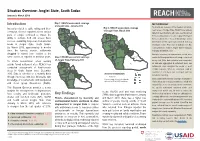

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

UNICEF South Sudan Humanitarian Situation August 2019

UNICEF SOUTH SUDAN SITUATION REPORT August 2019 South Sudan Humanitarian Lunch time at Juba Na Bari primary school in Juba. School meals provide at least one nutritious meal a Situation Report day for the children and give them the energy they need to concentrate. Photo: UNICEF South Sudan/De La Guardia AUGUST 2019: SOUTH SUDAN SITREP #135 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights •UNICEF and implementing partners distributed essential educational 1.83 million supplies (exercise books, pens, pencils, rulers, school bags, hygiene Internally displaced persons (IDPs) supplies) to 9,326 learners (including 3,989 girls) in 13 schools in Eastern (OCHA South Sudan Humanitarian Snapshot, July 2019) Equatoria. In Yambio teaching and learning materials, including students’ kits and other supplies were distributed to 6,380 children (3,334 girls; 3046 boys). 2.32 million South Sudanese refugees in •Additionally, all 32 released children from opposition forces in July 2019 neighbouring countries have begun receiving reintegration services in their communities through (UNHCR Regional Portal, South Sudan Situation coordinated case management services. 31 August 2019) •In 2019, no suspected cases of cholera have been reported. Cholera prevention activities continue to mitigate the risk of cholera outbreaks in 6.35 million hotspots. UNICEF and partners have reviewed the cholera preparedness South Sudanese facing acute food plan for 2019 in readiness for expected events in the country. insecurity or worse (August 2019 Projection, Integrated Food Security Phase Classification)