The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interaction Between International Aid and South Sudanese

Lost in Translation: The interaction between international humanitarian aid and South Sudanese accountability systems September 2020 This research was conducted by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF) in August and September 2019 and was funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan. The CSRF is implemented by a consortium of the NGOs Saferworld and swisspeace. It is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. This research would not have been possible without the South Sudanese and international aid actors who generously gave their time and insights. It is dedicated to the South Sudanese aid workers who tirelessly balance their personal and professional cultures to deliver assistance to those who need it. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology and limitations ........................................................................................................................... -

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

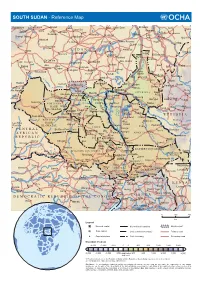

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map Kebkabiya El Fashir Abyad Bara Umm Dam El Kawa Ermil Nahl Doka Umm Bel Sennar Tawila Dirra Umm El Hilla Iyal Es Suki El Hawata Keddada Mahbub El Obeid Rabak Jebel Shangil Tobay Wad Banda Dud Singa Gallabat Wada`ah Umm Rawaba En Nahud El Rahad Higar Galegu El Jebelein Kas Taweisha S U D A N El Abbasiya Nyala Dilling Kortala Dangur El Odaiya Geigar Sharafa Delami Ed Damazin Rashad Renk e l El Barun Ed Da`ein i El Lagowa Abu Jibaiha Edd El Fursan N Babanusa e Heiban t Abu Abu i Bau Guba Ragag h Matariq Kulshabi Bikori Gabra W El Muglad Kadugli Kologi Keili Mumallah Umm Ulu Buram Keilak Talodi Barbit Wadega Belfodiyo Qardud Kaka Paloich Tungaru Junguls Asosa Radom Riangnom Sumeih El Melemm Oriny Kodok Mendi Boing Bambesi Hofrat Naam Fagwir Aboke en Nahas Malakal Nejo Abyei UPPER NILE Daga Bentiu Gimbi Bai War-awar Fangak Malwal Post Kafia Pan Nyal Mayom Kingi Malualkon Abwong Wang Kai Fagwir Kan Sobat Banyjiel Gidami Sadi Aweil Wun Rog Yubdo Gossinga UNITY Gumbiel Nasser NORTHERN Gogrial Nyerol Malek Thul Raga BAHR Akop Leer Mogogh Biel Bure Metu Wun Gambela EL GHAZAL WARRAP Ayod Waat Abay Gore Kwajok Shwai Adok Atiedo Warrap Fathai Faddoi Jonglei Canal Tor Deim Zubeir Madeir E T H I O P I A Bisellia Bir Di Duk Fadiat Akobo WESTERN Wau Gech`a Lol Mbili Duk Kongettit Les Trois BAHR Wakela Atum Faiwil Tepi Riviêres EL GHAZAL Tonj Shambe Peper Pochalla LAKES Kongor C E N T R A L Bo River Post Rafili Giamciar Teferi Rumbek Lau Akelo Palwal Jonglei JONGLEI Pibor A F R I C A N Ubori Akot Pibor Yirol Kantiere R E P U -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard. -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

An Analysis of Pibor County, South Sudan from the Perspective of Displaced People

Researching livelihoods and services affected by conflict Livelihoods, access to services and perceptions of governance: An analysis of Pibor county, South Sudan from the perspective of displaced people Working Paper 23 Martina Santschi, Leben Moro, Philip Dau, Rachel Gordon and Daniel Maxwell September 2014 About us Secure Livelihoods Research Consortium (SLRC) aims to generate a stronger evidence base on how people make a living, educate their children, deal with illness and access other basic services in conflict-affected situations (CAS). Providing better access to basic services, social protection and support to livelihoods matters for the human welfare of people affected by conflict, the achievement of development targets such as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and international efforts at peace- and state-building. At the centre of SLRC’s research are three core themes, developed over the course of an intensive one- year inception phase: . State legitimacy: experiences, perceptions and expectations of the state and local governance in conflict-affected situations . State capacity: building effective states that deliver services and social protection in conflict- affected situations . Livelihood trajectories and economic activity under conflict The Overseas Development Institute (ODI) is the lead organisation. SLRC partners include the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA) in Sri Lanka, Feinstein International Center (FIC, Tufts University), the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU), the Sustainable Development Policy -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The 8Th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan

The 8th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan Vaccines Work. Do Your Part! Submitted by the CORE Group Polio Project, South Sudan July 2018 INTRODUCTION This report documents efforts of South Sudan’s CORE Group Polio Project (CGPP) during the 8th African Vaccination Week (AVW) held in late April 2018. USAID provides funding for the CGPP’s immunization activities in 11 select counties in South Sudan. The brief highlights the implementation of program activities during AVW for the underserved, marginalized and hard-to-reach populations in Akobo County. From April 23 to April 29, CORE Group South Sudan collaborated with the Universal Network for Knowledge & Empowerment Agency (UNKEA), WHO, UNICEF, Nile Hope, International Medical Corps, and the Akobo County Health Department (CHD) that represents the Republic of South Sudan’s Ministry of Health. The main goal of the annual initiative is to strengthen immunization programs in South Sudan and to draw attention to the right of every child and woman to be protected from vaccine-preventable diseases. The theme for this year’s AVW was “Vaccines work. Do your part!” During the 2018 AVW, CORE Group undertook a variety of activities aimed at raising awareness through advocacy and social mobilization activities to promote the valuable benefits of immunization. These efforts resulted in increased numbers of children and women vaccinated through routine immunization outreach activities in Akobo County. SELECTING AKOBO COUNTY FOR AVW Akobo County is located in northeast South Sudan in Jonglei State and is situated near the international border of the Gambella Region of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia.