RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018

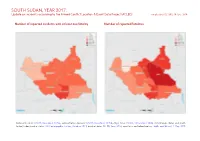

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, June 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 604 300 3351 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 404 299 1348 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 2 Strategic developments 120 0 0 Riots/protests 46 1 3 Methodology 3 Remote violence 25 3 17 Conflict incidents per province 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1200 603 4719 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). 2 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Methodology an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province is known. -

Principales Movimientos Rebeldes Armados Del Sur De Sudán

Humania del Sur. Año 11, Nº 20. Enero-Junio, 2016. Alfredo Langa Herrero Principales movimientos rebeldes armados del sur de Sudán... pp. 43-55. Principales movimientos rebeldes armados del sur de Sudán Alfredo Langa Herrero Universidad Pablo de Olavide (Sevilla, España) Universidad Alice Salomon (Berlín, Alemania) [email protected] Resumen En este artículo se presenta una descripción detallada de los principales grupos armados que han actuado en el sur de Sudán desde la independencia hasta la fundación de la República de Sudán del Sur, como consecuencia del escenario del confl icto armado que ha vivido el país durante prácticamente toda su existencia. El carácter y la evolución de dichos grupos ha sido muy diversa y su desarrollo no se ha limitado al sur del país, sino también al norte, donde la represión ejercida por los sucesivos gobiernos centrales ha propiciado la organización de diversas formas de resistencia y oposición armada. Palabras clave: Sudán, Guerra, Grupos armados, Rebeldes, Oposición. Main Armed Rebel Movements in Southern Sudan Abstract Th is article introduces a detailed description of the main armed groups that have been acting in the southern territories of Sudan, until the foundation of the Republic of South Sudan as a result of the armed confl ict the country has faced during practically the whole of its existence. Th e character and evolution of those groups has been quite diverse and their development has not been circumscribed to the South, for they have also arisen in the North, where armed repression by the successive central governments has yielded diverse forms of resistance and armed opposition. -

South Sudan: Force Protection Map As of October 2018 White Nile Sennar

South Sudan: Force Protection map as of October 2018 White Nile Sennar The map is shown where the road require force protection for convoy and access denied. Girbanat ! Renk Manyo ! Dakona! SUDAN ! El-galhak Renk ! Kaka Melut ! ! Paloich ! Melut ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wuntau ! ! ! ! ! ! Yida ! ! ! o Adar Bunj ! ! ! ! ! Fashoda o ! Rom ! Pariang ! ! ! ! ! Guel Guk an ! Kodok! Mab ! Malakal ! ! ! ! Akoka ! ! ! ! ! ! Biu Panyikang ! ! ! Agarak ! ! Malual ! Abiemnhom Tonga ! P ! ! o ! Malakal Baliet ! ! ! ! ! Abiemnom ! Wath Wang! Kech ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Banglai ! Aweil North ! Pul Luthni Pakoi ! Baliet Aweil ! ! !! ! Udier Bentiu Keew ! Nyinthok Gok-machar ! East Twic ! P Longochuk ! Mayom o ! Guit ! Chotbora Raga ! Wanyjok Akoc Rubkona Paguir Canal/Pigi ! Chuei ! ! Mayom ny ! Turalei ! Luakpi Warweng Chelkou Yargot ! Guit Kuon ! ! Pakor Wunrok Nhialdu ! Toch ! Aweil West ! ! Mayenjur k igi Mutthiang Fanga Canal/P ! Dome ! Nasir ! ! Ying Juong Aweil Gogrial Gogrial ! ! Nyadin ! Aroyo P ! Dindin Duar Pagil West East ! ! Ulang Maiwut Gossinga ! ! Buaw Nyirol ! Aweil Koch ! ! ! Nasser ! Gabir ! ! Liet-nhom ! Kandag! ! South ! Nyirol ! Haat ! Lankien ! ! Gogrial Ulang ! Raja Elok ! Koch Kosho ! Pagak ! ! Kull Bukteng ! AweilC entre Bar Mayen PKuajok Akop !o!Leer ! ! Ghanna Lunyaker Mayendit ! Walgak Thonyor ! Adok Ayod Pulchuol ! ! Ayod Tanyang ! Rualbet Mayendit! Jwong ! Pathai ! ! Yieth-liet Warrap ! ! ! ! Kaikuiny ! ! Sopo ! Thar-kueng ! Leer Wanding Pabuong ETHIOPIA Tonj ! Romich ! Kier Madol ! ! North ! -

Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan's Equatoria

SPECIAL REPORT NO. 493 | APRIL 2021 UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org Conflict and Crisis in South Sudan’s Equatoria By Alan Boswell Contents Introduction ...................................3 Descent into War ..........................4 Key Actors and Interests ............ 9 Conclusion and Recommendations ...................... 16 Thomas Cirillo, leader of the Equatoria-based National Salvation Front militia, addresses the media in Rome on November 2, 2019. (Photo by Andrew Medichini/AP) Summary • In 2016, South Sudan’s war expand- Equatorians—a collection of diverse South Sudan’s transitional period. ed explosively into the country’s minority ethnic groups—are fighting • On a national level, conflict resolu- southern region, Equatoria, trig- for more autonomy, local or regional, tion should pursue shared sover- gering a major refugee crisis. Even and a remedy to what is perceived eignty among South Sudan’s con- after the 2018 peace deal, parts of as (primarily) Dinka hegemony. stituencies and regions, beyond Equatoria continue to be active hot • Equatorian elites lack the external power sharing among elites. To spots for national conflict. support to viably pursue their ob- resolve underlying grievances, the • The war in Equatoria does not fit jectives through violence. The gov- political process should be expand- neatly into the simplified narratives ernment in Juba, meanwhile, lacks ed to include consultations with of South Sudan’s war as a power the capacity and local legitimacy to local community leaders. The con- struggle for the center; nor will it be definitively stamp out the rebellion. stitutional reform process of South addressed by peacebuilding strate- Both sides should pursue a nego- Sudan’s current transitional period gies built off those precepts. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS UPDATE September 2014

SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS UPDATE September 2014 SUDAN Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Melut Borders (MSF) has more than 3,300 local Yida Upper Maban staff and 350 international staff working in Abyei Nile Pamat Agok Malakal State Northern ETHIOPIA South Sudan and the neighbouring countries Bentiu Bahr Unity El Ghazal as part of its response to the humanitarian Aweil Leer Gogrial Jikmir Pagak Lankien Kuacjok crisis. Letchuor Mayendit Yuai Itang Warrap Tiergol Western Wau Bahr Nyal El Ghazal Jonglei At present, MSF operates 25 projects in 8 Lakes Rumbek states of South Sudan, including Unity, Upper CENTRAL Lekuongole Pibor AFRICAN Bor Gumuruk Nile and Jonglei states where the conflict REPUBLIC Western Awerial Equatoria has taken a particularly heavy toll on the Eastern population. Teams are responding to various Equatoria health needs including surgery, obstetrics, Yambio Juba Torit Central Equatoria Nadapal malaria, kala azar, vaccinations against- Existing intervention Nimule preventable diseases and malnutrition. Barutuku KENYA Dzaipi New intervention Nyumanzi DEMOCRATIC Ayilo Refugee Camps MSF calls on all parties to respect medical REPUBLIC UGANDA Violence in hospitals OF CONGO facilities, to allow aid organisations access to Directly aected by violence affected communities and to allow patients Indirectly aected by violence 0 100 200 km to receive medical treatment irrespective of Population migration 0 100 mi their origin or ethnicity. MSF in Numbers 15 December 2013–September 2014 498,495 29,919 2,888 12,702 11,587 Outpatient Consultations Inpatient Admissions War Wounded Treated Deliveries Children Received Nutrition of which of which and treatment as Outpatients 202,187 15,101 3,378 6,170 2,468 Children admitted to Inpatient Surgeries Performed Vaccinations Children Under 5 years Children Under 5 years Therapeutic Feeding Centres Nutrition Data in the above table from March 2014 to August 2014. -

Final Report

THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Rural Development, Upper Nile State THE PROJECT FOR COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING AND SUPPORT FOR URGENT DEVELOPMENT ON SOCIAL ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE IN MALAKAL TOWN IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT JULY 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. EI RECS INTERNATIONAL INC. JR KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. 14-122 The Project for Comprehensive Planning and Support for Urgent Development on Social Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town in the Republic of South Sudan Project Area Malakal Air Port ✈ Outer Ring Road Ring Road Ring Nile River Nile LBT Road-1 M al ak al Ri ve LB r T Po Ro ad- MoPI&RD 3 LBT Road-1 LEGEND: :Block Boundary :Road :River :Forest :Grassland :Idle Land (Sand and Mud) :Shrub Urgnt Development Support Projects :Water Treatment Plant :Water Pipe :Water Public Tab :Malakal Port :LBT Road PROJECT LOCATION MAP Final Report The Project for Comprehensive Planning and Support for Urgent Development on Social Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town in the Republic of South Sudan Photographs Present Situation of Socio-Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town 1 Water Treatment Plant of SSUWC Water pipes are detariorated and damaged, (Filter Tank) resulting in high ratio of non-revenue water Malakal Port (Cargo Jetty) Malakal Port (Passenger Jetty) Community Road (Black and Clayey Soil Community roads easily get muddy in rainy called Black Cotton Soil) season. LBT Construction Site (Upper -

Experiences from South Sudan

Security Promotion Seen from Below: Experiences from South Sudan Rens Willems (CCS) Hans Rouw (IKV Pax Christi) Working Group Community Security and Community-based DDR in Fragile States September 2011 i Working Group Members: Centre for Conflict Studies (CCS), Utrecht University Centre for International Conflict Analysis and Management (CICAM), Radboud University Nijmegen Conflict Research Unit (CRU) of the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’ European Centre for Conflict Prevention (ECCP) IKV Pax Christi Netherlands Ministry of Defence Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs PSO (Capacity Building in Developing Countries Dutch Council for Refugees Authors: Rens Willems (CCS) Hans Rouw (IKV Pax Christi) This publication is an outcome of the in 2008 established ‘Network for Peace, Security and Development’. The Network aims to support and encourage the sharing of expertise and cooperation between the different Dutch sectors and organisations involved in fragile states. The PSD Network is an initiative under the Schokland Agreements in 2007. More information on the PSD Network en other millennium agreements: www.milleniumakkoorden.nl The views expressed and analysis put forward in this report are entirely those of the authors in their professional capacity and cannot be attributed to the Peace, Security and Development Network and / or partners involved in its working groups and/ or the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs Executive Summary This report is based on seven weeks of field research in Jonglei, WES and EES, and was undertaken shortly after the results of the referendum for independence were declared. South Sudan was preparing for its official independence on 9 July 2011, after decades of cataclysmal conflict in which tensions within the south have been exacerbated, and development hardly took place. -

Institute For

INSTITUTE FOR SECURITY STUDIES INTERVIEW WITH DR LAM AKOL OF THE JUSTICE PARTY AFRICAN SECURITY ANALYSIS PROGRAMME INTERVIEW, KHARTOUM 31 MAY 2003 Introduction Dr. Lam Akol was a senior member of the SPLM/A before joining Dr. Riek Machar in a rebellion that split the mother party. He then broke from Dr. Riek, after which he signed the Fashoda Agreement with the government in 1997 and became the Minister of Transport. Dr. Akol held this position until a year ago. He is the author of ‘SPLM/SPLA: Inside an African Revolution’ and is currently a leading member of the opposition Justice Party. ASAP conducted this interview with Dr. Lam on 31 May 2003 in Khartoum. Assessing the current IGAD peace process Dr. Akol was very optimistic about the outcome of the peace process in his meeting with ASAP. However, he follows Special Sudan Envoy General Lazarus Sumbeiywo and others who expect that negotiations will extend beyond the end of June, the anticipated completion date. While acknowledging that both the SPLM/A and GoS were highly apprehensive about the process and outcome, Dr. Akol said that circumstances dictate a final peace agreement. He said the parties ‘do not have the freedom to indefinitely delay the outcome’. The Sudanese people, whether in the north or the south, want an agreement. The mediators, and in particular the US (which plays a critical role in the negotiations) understand this very well and this provides them with considerable leverage. The Sudanese will ‘cling to the agreement. It will be an agreement of all the Sudanese and not just the parties in the negotiations’. -

Clanship, Conflict and Refugees: an Introduction to Somalis in the Horn of Africa

CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA Guido Ambroso TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I: THE CLAN SYSTEM p. 2 The People, Language and Religion p. 2 The Economic and Socials Systems p. 3 The Dir p. 5 The Darod p. 8 The Hawiye p. 10 Non-Pastoral Clans p. 11 PART II: A HISTORICAL SUMMARY FROM COLONIALISM TO DISINTEGRATION p. 14 The Colonial Scramble for the Horn of Africa and the Darwish Reaction (1880-1935) p. 14 The Boundaries Question p. 16 From the Italian East Africa Empire to Independence (1936-60) p. 18 Democracy and Dictatorship (1960-77) p. 20 The Ogaden War and the Decline of Siyad Barre’s Regime (1977-87) p. 22 Civil War and the Disintegration of Somalia (1988-91) p. 24 From Hope to Despair (1992-99) p. 27 Conflict and Progress in Somaliland (1991-99) p. 31 Eastern Ethiopia from Menelik’s Conquest to Ethnic Federalism (1887-1995) p. 35 The Impact of the Arta Conference and of September the 11th p. 37 PART III: REFUGEES AND RETURNEES IN EASTERN ETHIOPIA AND SOMALILAND p. 42 Refugee Influxes and Camps p. 41 Patterns of Repatriation (1991-99) p. 46 Patterns of Reintegration in the Waqoyi Galbeed and Awdal Regions of Somaliland p. 52 Bibliography p. 62 ANNEXES: CLAN GENEALOGICAL CHARTS Samaal (General/Overview) A. 1 Dir A. 2 Issa A. 2.1 Gadabursi A. 2.2 Isaq A. 2.3 Habar Awal / Isaq A.2.3.1 Garhajis / Isaq A. 2.3.2 Darod (General/ Simplified) A. 3 Ogaden and Marrahan Darod A. -

Barbarian Beasts Or Mothers of Invention Relation of Gendered Fighter and Citizen Images Dissertation by Annette Weber

Barbarian Beasts or Mothers of Invention Relation of Gendered Fighter and Citizen Images with a specific case study on Southern Sudan Dissertation by Annette Weber Fachbereich Politik- und Sozialwissenschaften Freie Universität Berlin July 2006 Annette Weber betreut von Prof. Dr. Marianne Braig/ Erstgutachterin Prof. Dr. Ute Luig/ Zweitgutachterin Verteidigt am 23. April 2006 Magna cum laude 2 To you Meret! you rule my world 3 Acknowledgement: To those staying with me in times of tension. And those who kept me happy. To all my friends who brought life and fun to me and my house. To my family who hardly ever asked why this is still going on but never gave up believing it will be done. To the women in Sudan who took me in – regardless, who talked to me – in spite of, who inspired me with their clarity and power, who kept their friendship over all these years, who questioned and critizised and challenged. To the women in Eritrea who were disillusioned but new their strength and will never go back. To all the people, women, men and children in the conflict areas of Chiapas, Los Angeles, Sudan, Darfur, Nuba Mountains, Upper Nile, Bahr el Ghazal, Equatoria, Khartoum, Cairo, Uganda, Eritrea, DR Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, who allowed me to take their thoughts, their experiences, their suffering and sorrow, their knowledge and hopes with me in my notebook. To Marianne Braig and Ute Luig who are my supervisors. To Ulrich Albrecht, who was my supervisor for many years. To Kris, who was reading it and re-reading it and kept on giving me the right words and grammar and encouragement.