1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advise the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state, and county levels. Cover photo: © UNDP/Sun-Ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword ........................................................................................................................... .ii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... -

South Sudan Country Portfolio

South Sudan Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2013. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Foundation for manages a portfolio of 9 projects and one Cooperative Agreement. Tom Coogan, Regional Director Youth Initiative Total active commitment is $737,000. Regional Director Albino Gaw Dar, Director Country Strategy: The program focuses on food security and Email: [email protected] Tel: +211 955 413 090 export-oriented products. Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Kanybek General Trading and 2015-2018 $98,772 Sector: Agro-Processing (Maize Milling) Investment Company Ltd. Location: Mugali, Eastern Equatoria State 4155-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to build Kanybek’s capacity in business and financial management. The funds will also build technical capacity by providing training in sustainable agriculture and establishing a small milling facility to process raw maize into maize flour. Kajo Keji Lulu Works 2015-2018 $99,068 Sector: Manufacturing (Shea Butter) Multipurpose Cooperative Location: Kajo Keji County, Central Equatoria State Society (LWMCS) Summary: The project funds will be used to develop LWMCS’s capacity in financial and 4162-SSD business management, and to improve its production capacity by establishing a shea nut purchase fund and purchasing an oil expeller and related equipment to produce grade A shea butter for export. Amimbaru Paste Processing 2015-2018 $97,523 Sector: Agro-Processing (Peanut Paste) Cooperative Society (APP) Location: Loa in the Pageri Administrative Area, Eastern Equatoria State 4227-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to improve the business and financial management of APP through a series of trainings and the hiring of a management team. -

Solar Powered Transmission: a Case Study from South Sudan

Figure 1 – Solar Panels, viewed from above Solar Powered Transmission: A Case Study from South Sudan By Issa Kassimu, Natalie Chang and Ann Charles On behalf of The Radio Community and Internews Version 1.0, November 2016 About The Radio Community The Radio Community (TRC) is a network of community radio stations in South Sudan that reach an estimated 2.1 million potential listeners. These include Mayardit FM in Turalei, Warrap State; Nhomlaau FM in Malualkon, Northern Bahr el Ghazal State; Singaita FM in Kapoeta, Eastern Equatoria State; Mingkaman FM in Awerial County, Lakes State; and Nile FM in Malakal, Upper Nile State (operated in partnership with Internews’ Humanitarian Information Services). Stations in Leer and Nasir are currently off-air due to conflict. About Internews Internews is an international non-profit organization whose mission is to empower local media worldwide to give people the news and information they need, the ability to connect and the means to make their voices heard. Internews provides communities the resources to produce local news and information with integrity and independence. With global expertise and reach, Internews trains both media professionals and citizen journalists, introduces innovative media solutions, increases coverage of vital issues and helps establish policies needed for open access to information. Internews operates internationally, with administrative centers in California, Washington DC, and London, as well as regional hubs in Bangkok and Nairobi. Formed in 1982, Internews has worked in more than 90 countries, and currently has offices in Africa, Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Latin America and North America. Internews Network is registered as a 501(c)3 organization in California, EIN 94-302-7961. -

Principales Movimientos Rebeldes Armados Del Sur De Sudán

Humania del Sur. Año 11, Nº 20. Enero-Junio, 2016. Alfredo Langa Herrero Principales movimientos rebeldes armados del sur de Sudán... pp. 43-55. Principales movimientos rebeldes armados del sur de Sudán Alfredo Langa Herrero Universidad Pablo de Olavide (Sevilla, España) Universidad Alice Salomon (Berlín, Alemania) [email protected] Resumen En este artículo se presenta una descripción detallada de los principales grupos armados que han actuado en el sur de Sudán desde la independencia hasta la fundación de la República de Sudán del Sur, como consecuencia del escenario del confl icto armado que ha vivido el país durante prácticamente toda su existencia. El carácter y la evolución de dichos grupos ha sido muy diversa y su desarrollo no se ha limitado al sur del país, sino también al norte, donde la represión ejercida por los sucesivos gobiernos centrales ha propiciado la organización de diversas formas de resistencia y oposición armada. Palabras clave: Sudán, Guerra, Grupos armados, Rebeldes, Oposición. Main Armed Rebel Movements in Southern Sudan Abstract Th is article introduces a detailed description of the main armed groups that have been acting in the southern territories of Sudan, until the foundation of the Republic of South Sudan as a result of the armed confl ict the country has faced during practically the whole of its existence. Th e character and evolution of those groups has been quite diverse and their development has not been circumscribed to the South, for they have also arisen in the North, where armed repression by the successive central governments has yielded diverse forms of resistance and armed opposition. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government. -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Project Proposal

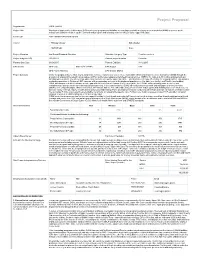

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

Southern Sudan News Bulletin ______

Southern Sudan News Bulletin ___________________________________________________________________________ An Overview of UN Activities in Southern Sudan Published by the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) _____________________________________________________________________ Vol. 4 Issue No.1 January 2009 Highlights: ¾ Thousands flee LRA attacks ¾ Sudan marks fourth CPA anniversary ¾ Former SPLA combatants turned into Prison Services Wardens ¾ Misseriya still in Southern Kordofan ¾ Planning underway for Tri-State Peace Conference ¾ Data compilation for essential services in Lakes State completed . Sector I – Juba Sudan Marks fourth CPA anniversary Thousands flee LRA attacks On January 9, Sudan marked the fourth Thousands of internally displaced persons anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace (IDPs) and refugees fleeing attacks by Agreement (CPA) that ended 21 years of Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebels have conflict between northern and southern poured into Western Equatoria State, Sudan in the Upper Nile State capital of prompting Governor Jemma Nunu Kumba to Malakal. The ceremony, which was attended launch a humanitarian appeal for by both the President of the Government of assistance. The displacement follows a joint National Unity (GONU), Omar Al Bashir, and military offensive by Ugandan and the First Vice-President of the GONU, Salva Congolese forces against the LRA that was Kiir, drew thousands of Sudanese to the launched on 14 December. The IDPs and city’s stadium. refugees, most of whom come from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), During the celebrations, President Bashir moved into Sudan after LRA attacks on and Vice-President Kiir, who is also their villages killed hundreds and led to the president of the Government of Southern abduction of women, children and even Sudan (GoSS), inaugurated the Malakal men. -

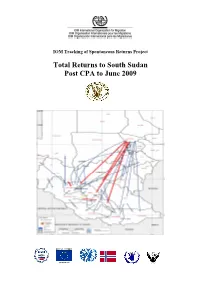

Total Returns to South Sudan Post CPA to June 2009

IOM Tracking of Spontaneous Returns Project Total Returns to South Sudan Post CPA to June 2009 Table of Contents Acknowledgements..................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary..................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Background....................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Objectives ......................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Methodology..................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. En-route Tracking............................................................................................................................. 5 3.2. Area of Return Tracking................................................................................................................... 6 4. Capacity Building of SSRRC and VRRC......................................................................................... 6 5. Total Estimated Number of Returns ................................................................................................. 8 6. Analysis of Area of Return - Cumulative Data, February 2007 to June 2009................................ 10 6.1. Total -

South Sudan Rapid Response Ebola 2019

RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS YEAR: 2019 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS SOUTH SUDAN RAPID RESPONSE EBOLA 2019 19-RR-SSD-33820 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR ALAIN NOUDÉHOU REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After-Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. 10 October 2019 The AAR took place on 10 October 2019, with the participation of WHO, UNICEF, IOM, WFP, and the Ebola Secretariat (EVD Secretariat). b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report on the Yes No use of CERF funds was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team. The report was not discussed within the Humanitarian Country Team due to time constraints; however, they received a draft of the completed report for their review and comment as of the 25 October 2019. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant Yes No government counterparts)? The final version of the RC/HC report was shared with CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, as well as with cluster coordinators and the EVD Secretariat, as of 16 October 2019. 2 PART I Strategic Statement by the Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator South Sudan is considered to be one of the countries neighbouring the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) at highest risk of Ebola importation and transmission. Thanks to the allocation of USD $2.1 million from the Central Emergency Relief Fund Ebola preparedness in South Sudan, including the capacity to detect and respond to Ebola, has been strengthened. -

Human Security in Sudan: the Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission

Human Security in Sudan: The Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission Prepared for the Minister of Foreign Affairs Ottawa, January 2000 Disclaimer: This report was prepared by Mr. John Harker for the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. The views and opinions contained in this report are not necessarily those of the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. 1 Human Security in Sudan: Executive Summary 1 Introduction On October 26, 1999, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lloyd Axworthy and the Minister for International Co-operation, Maria Minna, announced several Canadian initiatives to bolster international efforts backing a negotiated settlement to the 43-year civil war in Sudan, including the announcement of an assessment mission to Sudan to examine allegations about human rights abuses, including the practice of slavery. There are few other parts of the world where human security is so lacking, and where the need for peace and security - precursors to sustainable development - is so pronounced. Canada's commitment to human security, particularly the protection of civilians in armed conflict, provides a clear basis for its involvement in Sudan and its support for the peace process. Charm Offensive, or Signs of Progress? Following the visit to Khartoum of an EU Mission, a political dialogue was launched by the European Union on November 11 1999. The EU was of the view that there has been sufficient progress in Sudan to warrant a renewed dialogue. In this view, there has been a positive change, and it is necessary to encourage the Sudanese, and push them further where there is need.