Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Christs of the Black Christs of by J. Penn De

The Black Christs of Africa A Bible of Poems By J. Penn de Ngong Above all, I am not concerned with Poetry. My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. Wilfred Owen, British Poet Poem 22 petition for partition We, the auto-government of the Republic of Ruralia, Voicing the will of the democratic public of Ruralia, Are writing to your Theocratic Union of Urbania. Our grievances are on the following discontentment: Firstly, your purely autocratic Government of Urbania, Has solely dishonoured and condemned the document That we all signed – and codenamed – “Bible of Peace”. You’ve violated its gospel, the cause of our fatal disagreement; Wealth: You’re feeding our autonomous nation with ration apiece. In your annual tour, compare our city – Metropollutant – of Ruralia With its posh sister city of Urbania, proudly dubbed Metropolitania. All our resources, on our watching, are consumed up in Urbania. Our intellectuals and workforce are abundant but redundant. Henceforth, right here, we demarcate to be independent! You are busy strategizing to turn Ruralia into Somalia: Yourselves landlords, creating warlords, tribal militia, And bribing our politicians to speak out your voice, And turning our villages into large ghettos of slum, And our own towns into large cities of Islam. With these experiences, we’ve no choice, But t’ ask, demand, fight... for our voice. They oft’ say the end justifies the means, We, Ruralians, must reform all our ruins; The first option: thru the ballot, Last action: bullet! J. Penn de Ngong (John Ngong Alwong Alith as known in his family) came into this world on a day nobody knows. -

Education in Emergencies, Food Security and Livelihoods And

D e c e m b e r 2 0 1 5 Needs Assessment Report Education in Emergencies, Food Security, Livelihoods & Protection Fangak County, Jonglei State, South Sudan Finn Church Aid By Finn Church Aid South Sudan Country Program P.O. Box 432, Juba Nabari Area, Bilpham Road, Juba, South Sudan www.finnchurchaid.fi In conjunction with Ideal Capacity Development Consulting Limited P.O Box 54497-00200, Kenbanco House, Moi Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected], [email protected] www.idealcapacitydevelopment.org 30th November to 10th December 2015 i Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... VII 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 FOOD SECURITY AND LIVELIHOOD, EDUCATION AND PROTECTION CONTEXT IN SOUTH SUDAN ............................... 1 1.2 ABOUT FIN CHURCH AID (FCA) ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT IN FANGAK COUNTY .................................................................................................. 2 1.4 PURPOSE, OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................... -

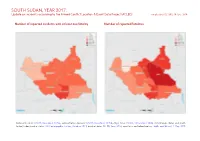

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018

SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 18 June 2018 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; Abyei Area: SSNBS, 1 December 2008; Ilemi triangle status and South Sudan/Sudan border status: UN Cartographic Section, October 2011; incident data: ACLED, June 2018; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Battles 604 300 3351 Conflict incidents by category 2 Violence against civilians 404 299 1348 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 2 Strategic developments 120 0 0 Riots/protests 46 1 3 Methodology 3 Remote violence 25 3 17 Conflict incidents per province 4 Non-violent activities 1 0 0 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 1200 603 4719 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). Disclaimer 5 Development of conflict incidents from 2012 to 2017 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, June 2018). 2 SOUTH SUDAN, YEAR 2017: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 18 JUNE 2018 Methodology an incident occured, or the provincial capital may be used if only the province is known. -

South Sudan Village Assessment Survey

IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY DATA COLLECTION: August-November 2019 COUNTIES: Bor South, Rubkona, Wau THEMATIC AREAS: Shelter and Land Ownership, Access and Communications, Livelihoods, Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies, Health, WASH, Education, Protection 1 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN CONTENTS RUBKONA COUNTY OVERVIEW 15 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 15 RETURN PATTERNS 15 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 16 KEY FINDINGS 17 Shelter and Land Ownership 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Access and Communications 17 LIST OF ACRONYMS 3 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 17 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 Livelihoods 18 BACKROUND 6 Health 19 WASH 19 METHODOLOGY 6 Education 20 LIMITATIONS 7 Protection 20 WAU COUNTY OVERVIEW 8 BOR SOUTH COUNTY OVERVIEW 21 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 8 RETURN PATTERNS 8 DISPLACEMENT DYNAMICS 21 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 9 RETURN PATTERNS 21 KEY FINDINGS 10 PAYAM CONTEXTUAL INFORMATION 22 KEY FINDINGS 23 Shelter and Land Ownership 10 Access and Communications 10 Shelter and Land Ownership 23 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 10 Access and Communications 23 Livelihoods 11 Markets, Food Security and Coping Strategies 23 Health 12 Livelihoods 24 WASH 13 Health 25 Protection 13 Education 26 Education 14 WASH 27 Protection 27 2 3 IOM DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX VILLAGE ASSESSMENT SURVEY SOUTH SUD AN LIST OF ACRONYMS AIDS: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome -

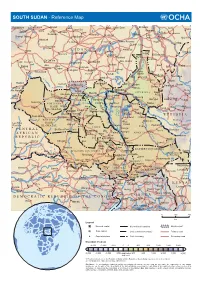

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map Kebkabiya El Fashir Abyad Bara Umm Dam El Kawa Ermil Nahl Doka Umm Bel Sennar Tawila Dirra Umm El Hilla Iyal Es Suki El Hawata Keddada Mahbub El Obeid Rabak Jebel Shangil Tobay Wad Banda Dud Singa Gallabat Wada`ah Umm Rawaba En Nahud El Rahad Higar Galegu El Jebelein Kas Taweisha S U D A N El Abbasiya Nyala Dilling Kortala Dangur El Odaiya Geigar Sharafa Delami Ed Damazin Rashad Renk e l El Barun Ed Da`ein i El Lagowa Abu Jibaiha Edd El Fursan N Babanusa e Heiban t Abu Abu i Bau Guba Ragag h Matariq Kulshabi Bikori Gabra W El Muglad Kadugli Kologi Keili Mumallah Umm Ulu Buram Keilak Talodi Barbit Wadega Belfodiyo Qardud Kaka Paloich Tungaru Junguls Asosa Radom Riangnom Sumeih El Melemm Oriny Kodok Mendi Boing Bambesi Hofrat Naam Fagwir Aboke en Nahas Malakal Nejo Abyei UPPER NILE Daga Bentiu Gimbi Bai War-awar Fangak Malwal Post Kafia Pan Nyal Mayom Kingi Malualkon Abwong Wang Kai Fagwir Kan Sobat Banyjiel Gidami Sadi Aweil Wun Rog Yubdo Gossinga UNITY Gumbiel Nasser NORTHERN Gogrial Nyerol Malek Thul Raga BAHR Akop Leer Mogogh Biel Bure Metu Wun Gambela EL GHAZAL WARRAP Ayod Waat Abay Gore Kwajok Shwai Adok Atiedo Warrap Fathai Faddoi Jonglei Canal Tor Deim Zubeir Madeir E T H I O P I A Bisellia Bir Di Duk Fadiat Akobo WESTERN Wau Gech`a Lol Mbili Duk Kongettit Les Trois BAHR Wakela Atum Faiwil Tepi Riviêres EL GHAZAL Tonj Shambe Peper Pochalla LAKES Kongor C E N T R A L Bo River Post Rafili Giamciar Teferi Rumbek Lau Akelo Palwal Jonglei JONGLEI Pibor A F R I C A N Ubori Akot Pibor Yirol Kantiere R E P U -

RVI Local Peace Processes in Sudan.Pdf

Rift Valley Institute ﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻷﺨدود اﻟﻌﻇﻴم Taasisi ya Bonde Kuu ySMU vlˆ yU¬T tí Machadka Dooxada Rift 东非大裂谷研究院 Institut de la Vallée du Rift Local Peace Processes in Sudan A BASELINE STUDY Mark Bradbury John Ryle Michael Medley Kwesi Sansculotte-Greenidge Commissioned by the UK Government Department for International Development “Our sons are deceiving us... … Our soldiers are confusing us” Chief Gaga Riak Machar at Wunlit Dinka-Nuer Reconciliation Conference 1999 “You, translators, take my words... It seems we are deviating from our agenda. What I expected was that the Chiefs of our land, Dinka and Nuer, would sit on one side and address our grievances against the soldiers. I differ from previous speakers… I believe this is not like a traditional war using spears. In my view, our discussion should not concentrate on the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer, but on the soldiers, who are the ones who are responsible for beginning this conflict. “When John Garang and Riek Machar [leaders of rival SPLA factions] began fighting did we understand the reasons for their fighting? When people went to Bilpam [in Ethiopia] to get arms, we thought they would fight against the Government. We were not expecting to fight against ourselves. I would like to ask Commanders Salva Mathok & Salva Kiir & Commander Parjak [Senior SPLA Commanders] if they have concluded the fight against each other. I would ask if they have ended their conflict. Only then would we begin discussions between the chiefs of Dinka and Nuer. “The soldiers are like snakes. When a snake comes to your house day after day, one day he will bite you. -

Initial Rapid Needs Assessment on Flood Disaster in Twic East County, Jonglei State

Coordinated Flood Disaster Assessment in the Former Twic East County Initial Rapid Needs Assessment On flood Disaster in Twic East County, Jonglei State July, 2019 Page 1 of 12 Coordinated Flood Disaster Assessment in the Former Twic East County Situation Overview Former Twic East County of Jonglei state composed of five Map Payams: Ajuong, Kongor, Lith, Nyuak, and Pakeer. According to the Fifth Population and Housing Census conducted in April 2008, Twic East County had a combined population of 8,5349 people, composed of 4,4039 males and 4,1310 female residents with 14326 Household (HHs) In the month of June 2019, there was a flooding in the former Twic East County which has affected all the five Payams. Nyuak, Kongor and Lith Payams were highly affected while Pakeer and Ajuong Payam were partly flooded. The flooding was caused by erratic and heavy rainfall which happened in the month of June 2019. For the last three years, there has been Twic East County heavy rainfall that causes flooding. The natural land scape of Twic East does not allow free water movement to downstream Affected population: 1547 HHS, total of 8722 people has and the water accumulation has increased in villages, especially been affected. Refer Annex 1 for in agricultural and grazing/pasture land. details. As rainy season is currently on its peak, flooding is expected to Displaced population: increase which might aggravate the situation before impact of Over 1000 HHS have been displaced.) the current flood is tackled and water level goes down. In addition, the rain condition in upper basin of Nile (from Central Key Priorities equatorial and Uganda) is expected to increase the river water Urgent seed vegetable seeds level and water level in swampy area (Sudd part of Twic East), supply for fresh food which will in turn causes breakage of primary dyke (which has production already some weak points) and add more crises in the county. -

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #2, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 December 7, 2018

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 DECEMBER 7, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Relief actor records at least 150 GBV cases in Bentiu during a 12-day period 5% 7% 20% UN records two aid worker deaths, 60 7 million 7% Estimated People in South humanitarian access incidents in October 10% Sudan Requiring Humanitarian USAID/FFP partner reaches 2.3 million Assistance 19% 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan – people with assistance in October December 2017 15% 17% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE 6.1 million Health (17%) Nutrition (15%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/FFP $402,253,743 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) September 2018 Shelter & Settlements (5%) 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $628,994,9784 2 million BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 Estimated IDPs in 84% 9% 5% South Sudan OCHA – November 8, 2018 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,760,121,951 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES 194,900 Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases KEY DEVELOPMENTS UNMISS – November 15, 2018 During a 12-day period in late November, non-governmental organization (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) recorded at least 150 gender-based violence (GBV) cases in Unity State’s Bentiu town, representing a significant increase from the approximately 2.2 million 100 GBV cases that MSF recorded in Bentiu between January and October. -

The 8Th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan

The 8th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan Vaccines Work. Do Your Part! Submitted by the CORE Group Polio Project, South Sudan July 2018 INTRODUCTION This report documents efforts of South Sudan’s CORE Group Polio Project (CGPP) during the 8th African Vaccination Week (AVW) held in late April 2018. USAID provides funding for the CGPP’s immunization activities in 11 select counties in South Sudan. The brief highlights the implementation of program activities during AVW for the underserved, marginalized and hard-to-reach populations in Akobo County. From April 23 to April 29, CORE Group South Sudan collaborated with the Universal Network for Knowledge & Empowerment Agency (UNKEA), WHO, UNICEF, Nile Hope, International Medical Corps, and the Akobo County Health Department (CHD) that represents the Republic of South Sudan’s Ministry of Health. The main goal of the annual initiative is to strengthen immunization programs in South Sudan and to draw attention to the right of every child and woman to be protected from vaccine-preventable diseases. The theme for this year’s AVW was “Vaccines work. Do your part!” During the 2018 AVW, CORE Group undertook a variety of activities aimed at raising awareness through advocacy and social mobilization activities to promote the valuable benefits of immunization. These efforts resulted in increased numbers of children and women vaccinated through routine immunization outreach activities in Akobo County. SELECTING AKOBO COUNTY FOR AVW Akobo County is located in northeast South Sudan in Jonglei State and is situated near the international border of the Gambella Region of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

Humanitarian Response Plan South Sudan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

Interethnic Conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging Ethnic Hatred Between the Lou Nuer and the Murle

Interethnic conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging ethnic hatred between the Lou Nuer and the Murle Yuki Yoshida* Abstract This article analyses the escalation of interethnic confl icts between the Lou Nuer and the Murle in Jonglei State of South Sudan. Historically, interethnic confl icts in Jonglei were best described as environmental confl icts, in which multiple ethnic groups competed over scarce resources for cattle grazing. Cattle raiding was commonly committed. The global climate change exacerbated resource scarcity, which contributed to intensifying the confl icts and developing ethnic cleavage. The type of confl ict drastically shifted from resource-driven to identity-driven confl ict after the 2005 government-led civilian disarmament, which increased the existing security dilemma. In the recent confl icts, there have been clear demonstrations of ethnic hatred in both sides, and arguably the tactics used amounted to acts of genocide. The article ends with some implications drawn from the Jonglei case on post-confl ict reform of the security sector and management of multiple identities. * Yuki Yoshida is a graduate student studying peacebuilding and conflict resolution at the Center for Global Affairs, New York University. His research interests include UN peacekeeping, post-conflict peacebuilding, democratic governance, humanitarian intervention, and the responsibility to protect. He obtained his BA in Liberal Arts from Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, CA, in 2012. 39 Yuki Yoshida Introduction After decades of civil war, the Republic of South Sudan achieved independence in July 2011 and was recognised as the newest state by the international community. However, South Sudan has been plagued by the unresolved territorial dispute over the Abyei region with northern Sudan, to which the world has paid much attention.