Education in Emergencies, Food Security and Livelihoods And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan - Crisis Fact Sheet #2, Fiscal Year (Fy) 2019 December 7, 2018

SOUTH SUDAN - CRISIS FACT SHEET #2, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2019 DECEMBER 7, 2018 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA1 FUNDING HIGHLIGHTS A GLANCE BY SECTOR IN FY 2018 Relief actor records at least 150 GBV cases in Bentiu during a 12-day period 5% 7% 20% UN records two aid worker deaths, 60 7 million 7% Estimated People in South humanitarian access incidents in October 10% Sudan Requiring Humanitarian USAID/FFP partner reaches 2.3 million Assistance 19% 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan – people with assistance in October December 2017 15% 17% HUMANITARIAN FUNDING Logistics Support & Relief Commodities (20%) Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (19%) FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE 6.1 million Health (17%) Nutrition (15%) USAID/OFDA $135,187,409 Estimated People in Need of Protection (10%) Food Assistance in South Sudan Agriculture & Food Security (7%) USAID/FFP $402,253,743 IPC Technical Working Group – Humanitarian Coordination & Info Management (7%) September 2018 Shelter & Settlements (5%) 3 State/PRM $91,553,826 USAID/FFP2 FUNDING $628,994,9784 2 million BY MODALITY IN FY 2018 1% TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE SOUTH SUDAN CRISIS IN FY 2018 Estimated IDPs in 84% 9% 5% South Sudan OCHA – November 8, 2018 U.S. In-Kind Food Aid (84%) 1% $3,760,121,951 Local & Regional Food Procurement (9%) TOTAL USG HUMANITARIAN FUNDING FOR THE Complementary Services (5%) SOUTH SUDAN RESPONSE IN FY 2014–2018, Cash Transfers for Food (1%) INCLUDING FUNDING FOR SOUTH SUDANESE Food Vouchers (1%) REFUGEES IN NEIGHBORING COUNTRIES 194,900 Estimated Individuals Seeking Refuge at UNMISS Bases KEY DEVELOPMENTS UNMISS – November 15, 2018 During a 12-day period in late November, non-governmental organization (NGO) Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) recorded at least 150 gender-based violence (GBV) cases in Unity State’s Bentiu town, representing a significant increase from the approximately 2.2 million 100 GBV cases that MSF recorded in Bentiu between January and October. -

Interethnic Conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging Ethnic Hatred Between the Lou Nuer and the Murle

Interethnic conflict in Jonglei State, South Sudan: Emerging ethnic hatred between the Lou Nuer and the Murle Yuki Yoshida* Abstract This article analyses the escalation of interethnic confl icts between the Lou Nuer and the Murle in Jonglei State of South Sudan. Historically, interethnic confl icts in Jonglei were best described as environmental confl icts, in which multiple ethnic groups competed over scarce resources for cattle grazing. Cattle raiding was commonly committed. The global climate change exacerbated resource scarcity, which contributed to intensifying the confl icts and developing ethnic cleavage. The type of confl ict drastically shifted from resource-driven to identity-driven confl ict after the 2005 government-led civilian disarmament, which increased the existing security dilemma. In the recent confl icts, there have been clear demonstrations of ethnic hatred in both sides, and arguably the tactics used amounted to acts of genocide. The article ends with some implications drawn from the Jonglei case on post-confl ict reform of the security sector and management of multiple identities. * Yuki Yoshida is a graduate student studying peacebuilding and conflict resolution at the Center for Global Affairs, New York University. His research interests include UN peacekeeping, post-conflict peacebuilding, democratic governance, humanitarian intervention, and the responsibility to protect. He obtained his BA in Liberal Arts from Soka University of America, Aliso Viejo, CA, in 2012. 39 Yuki Yoshida Introduction After decades of civil war, the Republic of South Sudan achieved independence in July 2011 and was recognised as the newest state by the international community. However, South Sudan has been plagued by the unresolved territorial dispute over the Abyei region with northern Sudan, to which the world has paid much attention. -

Tables from the 5Th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008

Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 CENSU OR S,S F TA RE T T IS N T E IC C S N A N A 123 D D β U E S V A N L R ∑σ µ U E A H T T I O U N O S S S C C S E Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 ii Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... x Foreword ....................................................................................................................... xiv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ xv Background and Mandate of the Southern Sudan Centre for Census, Statistics and Evaluation (SSCCSE) ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 History of Census-taking in Southern Sudan....................................................................... 2 Questionnaire Content, Sampling and Methodology ............................................................ 2 Implementation .............................................................................................................. 2 -

South Sudan Arabica Coffee Land Race Survey in Boma Germplasm Assessment and Conservation Project Report Dr

South Sudan Arabica Coffee Land Race Survey in Boma Germplasm Assessment and Conservation Project Report Dr. Sarada Krishnan Dr. Aaron P. Davis 1. Introduction and Background: Coffee is an extremely important agricultural commodity (Vega et al. 2003) produced in about 80 tropical countries, with an annual production of nearly seven million tons of green beans (Musoli et al. 2009). It is the second most valuable commodity exported by developing countries after oil, with over 75 million people depending on it for their livelihood (Vega et al. 2003; Pendergrast 2009). It is thought that coffee was introduced to Yemen from its origins in Ethiopia around the sixth century (Pendergrast 1999). From Yemen, two genetic bases spread giving rise to most of the present commercial cultivars of Arabica coffee grown worldwide (Anthony et al. 2002). The two sub-populations of wild coffee introduced from Ethiopia to Yemen underwent successive reductions in genetic diversity with the first reduction occurring with the introduction of coffee to Yemen 1,500 to 300 years ago (Anthony et al. 2002). Introduction of coffee to Java, Amsterdam, and La Réunion at the beginning of the 18th century led to further reductions in genetic diversity (Anthony et al. 2002). In addition to Ethiopia, wild plants of C. arabica were observed in the Boma Plateau of South Sudan (Thomas 1942; Meyer 1965) and Mount Marsabit in northern Kenya (Meyer 1965). A consortium led by Texas A&M University’s Norman Borlaug Institute for International Agriculture has been commissioned to support the John Garang University of Science and Technology (JG-MUST) of South Sudan. -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

SOUTH SUDAN Consolidated Appeal 2014 - 2016

SOUTH SUDAN Consolidated Appeal 2014 - 2016 UNOCHA Clusters Assess and analyze needs Clusters and HCT Humanitarian Country Monitor, review Team and Coordinator and report Set strategy and priorities HUMANITARIAN PLANNING PROCESS Organizations Clusters Mobilize resources Develop objectives, indicators, and implement response plans and projects OCHA Compile strategy and plans into Strategic Response Plans and CAP 2014-2016 CONSOLIDATED APPEAL FOR SOUTH SUDAN AAR Japan, ACEM, ACF USA, ACT/DCA, ACT/FCA, ACTED, ADESO, ADRA, AHA, AHANI, AMURT International, ARARD, ARC, ARD, ASMP, AVSI, AWODA, BARA, C&D, CAD, CADA, CARE International, Caritas CCR, Caritas DPO-CDTY, CCM, CCOC, CDoT, CESVI, Chr. Aid, CINA, CMA, CMD, CMMB, CORDAID, COSV, CRADA, CRS, CUAMM, CW, DDG, DORD, DRC, DWHH, FAO, FAR, FLDA, GHA, GKADO, GOAL, HCO, HELP e.V., HeRY, HI, HLSS, Hoffnungszeichen, IAS, IMC UK, Intermon Oxfam, INTERSOS, IOM, IRC, IRW, JUH, KHI, LCED, LDA, MaCDA, MAG, MAGNA, Mani Tese, MAYA, MEDAIR, Mercy Corps, MERLIN, MI, Mulrany International, NCDA, NGO Forum, Nile Hope, NPA, NPC, NPP, NRC, OCHA, OSIL, OXFAM GB, PAH, PCO, PCPM, PIN, Plan, PWJ, RedR UK, RI, RUWASSA, SALF, Samaritan's Purse, SC, SCA, SIMAS, SMC, Solidarités, SPEDP, SSUDA, SUFEM, TEARFUND, THESO, TOCH, UDA, UNDSS, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIDO, UNKEA, UNMAS, UNOPS, UNWWA, VSF (Belgium), VSF (Switzerland), WFP, WHO, World Relief, WTI, WV South Sudan, ZOA Refugee Care Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. Photo caption: Fishermen on the Nile River in South Sudan. -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

49A65b110.Pdf

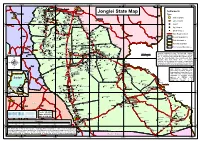

30°0'0"E 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Buheyrat No ") Popuoch Maya Sinyora Wath Wang Kech Malakal Dugang New Fangak Juaibor " Fatwuk " Pul Luthni Doleib Hill Fakur Ful Nyak " Settlements Rub-koni Ngwer Gar Keuern Fachop " Mudi Kwenek Konna Jonglei State Map Yoynyang Kau Keew Tidfolk " Fatach Fagh Atar Nyiyar Wunalong Wunakir Type Jwol Dajo ") Tiltil Torniok Atar 2 Machar Shol Ajok Fangak Kir Nyin Yar Kuo " Nur Yom Chotbora AbwongTarom ") State Capitals Bentiu Chuth Akol Fachod Thantok Kuleny Abon Abwong Jat Paguir Abuong Ayiot Ariath OLD FANGAK Fangak " ") Kot Fwor Lam Baar Shwai Larger Towns Fulfam Fajur Malualakon Tor Lil Riep ") Madhol ATAR N Rier Mulgak N " " " Mayen Pajok Foan Wuriyang Kan 0 0 ' " ' Kaljak Dier Wunlam Upper Nile Towns 0 Gon Toych Wargar 0 ° Akuem Toch Wunrok Kuey ° 9 Long Wundong Ayien Gwung Tur Dhiak Kuei 9 Fulkwoz Weibuini Dornor Tam Kolatong Wadpir Wunapith Nyinabot Big Villages Fankir Yarkwaich Chuai Twengdeng Mawyek Muk Tidbil Fawal Wunador Manyang Gadul Nyadin Wunarual Tel Luwangni Small Villages Rublik List Wunanomdamir Piath Nyongchar Yafgar Paguil Kunmir Toriak Akai Uleng Fanawak Pagil Fawagik Kor Nyerol Nyirol Main Road Network Nyakang Liet Tundi Wuncum Tok Rial Kurnyith Gweir Lung Nasser Koch Nyod Falagh Kandak Pulturuk Maiwut " Famyr Tar Turuk ") County Boundaries Jumbel Menime Kandag Dor " Dur NYIROL Ad Fakwan Haat Agaigai Rum Kwei Ket Thol Wor Man Lankien State Boundaries Dengdur Maya Tawil Raad Turu Garjok Mojogh Obel Pa Ing Wang Gai Rufniel Mogok Maadin Nyakoi Futh Dengain Mandeng Kull -

[email protected], Area Mapped Logcluster Office, UNOCHA Compound and Jebel Kajur, Juba South Sudan

Sani Mingyeir Sullu Oubbe Wada`ah Djiri Bajouggi Karaw Balla Nyama Ludung Margibba Arga Gertobak Dalia Zulumingtong Gostoweir El Rahad Gyaga Manawashi En Nahud Duraysah Kurbi Karbab Godoba Silo Arid Limo Menawashei Tebeldina Kurto Kulme Gabir Futajiggi Shurab Zulata Tanako Burbur Seingo Kalamboa Uraydimah Kass Attib Deleig Kalu Dilu Shearia Shaqq Bunzuga al Gawa Galgani Duma Garoula Tangya Korgusa Garsila Kagko Khamis Abu zor Amar Seilo Ballah Umm Marabba Gedid Mogara Dauro Shalkha Harun Tumbo Qawz Beringil Lerwa Baya Saq an Na`am Buhera Sineit Goldober Singeiwa Agra Nyala Labado Sereiwa Baddal Sigeir Dilling Kirarow Tumko Umm Sa Disa Um Kurdus Shaqq Girbanat Kasoleri Buronga Gerger Saheib Mabrouka al Huja El Lait Bendisi Diri Tono Abu Mukjar Ambara Deimbo Buddu El doma Gartaga Abou Sufyan Dalami Artala Shuwayy Rashad El Roseires Um Sarir @Adid Al Muturwed Dashi Wad Abu Kubum Dago Ed Damazin Tetene Keikei Hassib Gheid Renk Nurlei Um Boim Î Damba El kharaba West Lasirei Luma Solwong Murr Njumbeil Agi Abu Ghazal Qubba Girru Ajala Um La`ota Abu Marlenga Ma'aliah 1 Jawazat Karinka Hajar Wajage Markundi Al Marwahah Abu Ma'aliah 2 Banda Dimbala 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"EUmm 31°0'0"E 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E 36°0'0"E Timassi Ajura heitan Abu Edd el Faki Jibaiha Lujugo Milmeidi Gettin Ibrahim 42Bakau Fursan Kukur Kosua Dambar p Lagawa Sali Kulaykili Abu @ Tabanu Agabullah Adilla Wisko War e ho u se Aradeiba Gereida Manasis Anja C ap a ci t i e s 20 11 Katayla Muhajiriye Abu `Ud Heiban Um- 68Akoc Dukhun Gueighrin -

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January-March 2018

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January-March 2018 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage Map 3: REACH assessment coverage Bor Town, c) two FGDs for Ayod in Bor PoC. of Jonglei State, January 2018 of Jonglei State, March 2018 All this information is included in the data used Ongoing conflict in Jonglei continued for this Situation Overview. to negatively affect humanitarian needs among the population in the first quarter of This Situation Overview provides an update 2018. Clashes between armed groups and to key findings from the November 2017 1 pervasive insecurity, particularly in northern Situation Overview. The first section analyses Jonglei caused displacement among affected displacement and population movement in communities, negatively impacting the ability Jonglei during the first quarter of 2018, and the to meet their primary needs. second section evaluates access to food and basic services for both IDP and non-displaced REACH has been assessing the situation in Map 2: REACH assessment coverage communities. hard-to-reach areas in South Sudan since of Jonglei State, February 2018 December 2015, to inform the response Population Movement and of humanitarian actors working outside of Displacement formal settlement sites. This settlement data Levels of depopulation remained high but is collected across South Sudan on a monthly stable overall in most parts of Jonglei in the first basis. Between 2 January and 23 March, Assessed settlements quarter of 2018. The proportion of assessed REACH interviewed 1527 Key Informants Settement settlements in Jonglei reporting that half or (KIs) with knowledge of humanitarian needs Cover percentae o aeed ettement reative to the OCHA COD tota dataet more of the population had left remained in 710 settlements in 7 of the 11 counties in similar between December 2017 (45%) and Jonglei State. -

IRNA Report: Jiech, Ayod County, Jonglei State 13/14 May 2014

IRNA Report: Jiech, Ayod County, Jonglei State 13/14 May 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. Situation overview Ayod County is located in the northwest part of Jonglei state and borders Fangak and Khorflus Counties to the north, Nyirol and Uror Counties to the east, Duk County to the south and Unity State to the west. It is comprised of five Payams, namely Ayod, Mogok, Pajiek, Pagil, Kuachdeng and Wau. Ayod County and its environs are inhabited by Gaawar Nuer. It had a population of 139,282 people as per South Sudan Household Census of 2008. Jiech now hosts the County Administration. The community and county headquarters is currently calm, after being compelled to flee to following a SPLA offensive resulting in the capture of Ayod. On May 10th, OCHA received reports that up to an estimated 25,283 IDP’s were seeking refuge in Jiech Payam, Ayod County .In response an IRNA mission was launched through OCHA taking the lead and convening an Inter cluster Working Group for actors in Ayod County. The area normally has high levels of food insecurity and following the withdrawal of health actors, has lacked health interventions which has worsened over the last few weeks with IDPs fleeing their homes with no basic commodities. IDP’s reported are 25,283, however far fewer civilians were seen and the population will need to be verified as soon as possible.