Third Party Monitoring of the World Bank Rapid Results Health Project Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education in Emergencies, Food Security and Livelihoods And

D e c e m b e r 2 0 1 5 Needs Assessment Report Education in Emergencies, Food Security, Livelihoods & Protection Fangak County, Jonglei State, South Sudan Finn Church Aid By Finn Church Aid South Sudan Country Program P.O. Box 432, Juba Nabari Area, Bilpham Road, Juba, South Sudan www.finnchurchaid.fi In conjunction with Ideal Capacity Development Consulting Limited P.O Box 54497-00200, Kenbanco House, Moi Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected], [email protected] www.idealcapacitydevelopment.org 30th November to 10th December 2015 i Table of Contents ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................... VI EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................... VII 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 FOOD SECURITY AND LIVELIHOOD, EDUCATION AND PROTECTION CONTEXT IN SOUTH SUDAN ............................... 1 1.2 ABOUT FIN CHURCH AID (FCA) ....................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 HUMANITARIAN CONTEXT IN FANGAK COUNTY .................................................................................................. 2 1.4 PURPOSE, OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE OF ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................... -

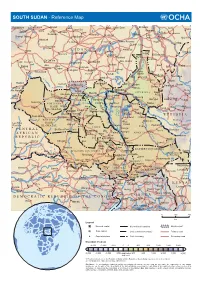

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map

SOUTH SUDAN - Reference Map Kebkabiya El Fashir Abyad Bara Umm Dam El Kawa Ermil Nahl Doka Umm Bel Sennar Tawila Dirra Umm El Hilla Iyal Es Suki El Hawata Keddada Mahbub El Obeid Rabak Jebel Shangil Tobay Wad Banda Dud Singa Gallabat Wada`ah Umm Rawaba En Nahud El Rahad Higar Galegu El Jebelein Kas Taweisha S U D A N El Abbasiya Nyala Dilling Kortala Dangur El Odaiya Geigar Sharafa Delami Ed Damazin Rashad Renk e l El Barun Ed Da`ein i El Lagowa Abu Jibaiha Edd El Fursan N Babanusa e Heiban t Abu Abu i Bau Guba Ragag h Matariq Kulshabi Bikori Gabra W El Muglad Kadugli Kologi Keili Mumallah Umm Ulu Buram Keilak Talodi Barbit Wadega Belfodiyo Qardud Kaka Paloich Tungaru Junguls Asosa Radom Riangnom Sumeih El Melemm Oriny Kodok Mendi Boing Bambesi Hofrat Naam Fagwir Aboke en Nahas Malakal Nejo Abyei UPPER NILE Daga Bentiu Gimbi Bai War-awar Fangak Malwal Post Kafia Pan Nyal Mayom Kingi Malualkon Abwong Wang Kai Fagwir Kan Sobat Banyjiel Gidami Sadi Aweil Wun Rog Yubdo Gossinga UNITY Gumbiel Nasser NORTHERN Gogrial Nyerol Malek Thul Raga BAHR Akop Leer Mogogh Biel Bure Metu Wun Gambela EL GHAZAL WARRAP Ayod Waat Abay Gore Kwajok Shwai Adok Atiedo Warrap Fathai Faddoi Jonglei Canal Tor Deim Zubeir Madeir E T H I O P I A Bisellia Bir Di Duk Fadiat Akobo WESTERN Wau Gech`a Lol Mbili Duk Kongettit Les Trois BAHR Wakela Atum Faiwil Tepi Riviêres EL GHAZAL Tonj Shambe Peper Pochalla LAKES Kongor C E N T R A L Bo River Post Rafili Giamciar Teferi Rumbek Lau Akelo Palwal Jonglei JONGLEI Pibor A F R I C A N Ubori Akot Pibor Yirol Kantiere R E P U -

Humanitarian Response Plan South Sudan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack

Resident Coordinator Support Office, Upper Nile State Briefing Pack Table of Contents Page No. Table of Contents 1 State Map 2 Overview 3 Security and Political History 3 Major Conflicts 4 State Government Structure 6 Recovery and Development 7 State Resident Coordinator’s Support Office 8 Organizations Operating in the State 9-11 1 Map of Upper Nile State 2 Overview The state of Upper Nile has an area of 77,773 km2 and an estimated population of 964,353 (2009 population census). With Malakal as its capital, the state has 13 counties with Akoka being the most recent. Upper Nile shares borders with Southern Kordofan and Unity in the west, Ethiopia and Blue Nile in the east, Jonglei in the south, and White Nile in the north. The state has four main tribes: Shilluk (mainly in Panyikang, Fashoda and Manyo Counties), Dinka (dominant in Baliet, Akoka, Melut and Renk Counties), Jikany Nuer (in Nasir and Ulang Counties), Gajaak Nuer (in Longochuk and Maiwut), Berta (in Maban County), Burun (in Maban and Longochok Counties), Dajo in Longochuk County and Mabani in Maban County. Security and Political History Since inception of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), Upper Nile State has witnessed a challenging security and political environment, due to the fact that it was the only state in Southern Sudan that had a Governor from the National Congress Party (NCP). (The CPA called for at least one state in Southern Sudan to be given to the NCP.) There were basically three reasons why Upper Nile was selected amongst all the 10 states to accommodate the NCP’s slot in the CPA arrangements. -

Tables from the 5Th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008

Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 CENSU OR S,S F TA RE T T IS N T E IC C S N A N A 123 D D β U E S V A N L R ∑σ µ U E A H T T I O U N O S S S C C S E Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 ii Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... x Foreword ....................................................................................................................... xiv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ xv Background and Mandate of the Southern Sudan Centre for Census, Statistics and Evaluation (SSCCSE) ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 History of Census-taking in Southern Sudan....................................................................... 2 Questionnaire Content, Sampling and Methodology ............................................................ 2 Implementation .............................................................................................................. 2 -

Republic of South Sudan EARLY WARNING and DISEASE

Early Warning and Disease Surveillance System Republic of South Sudan EARLY WARNING AND DISEASE SURVEILLANCE BULLETIN (IDP CAMPS AND COMMUNITIES) Week 48 24 – 30 November 2014 General Overview Completeness for weekly reporting decreased from 98% to 92% while timeliness decreased from 72% to 50% in week 48 when compared to week 47. Malaria remains the top cause of morbidity in week 48 with Malakal PoC having the highest incidence followed by Tongping, Bentiu, Bor and Lankien. During week 48, Malakal PoC had the highest incidence for malaria and ABD, while Bentiu PoC had the highest incidence for ARI and AWD. A total of three suspect measles cases were reported from Melut (1 case) and Lankien (2 cases) during week 48. There are no new HEV cases reported since week 47. The cumulative for HEV in Mingkaman remains at 124 cases including four deaths (CFR 3.23%). There are no new cholera cases reported since week 47. The cumulative remains at 6,421 cholera cases including 167 deaths (CFR 2.60%) from 16 counties in South Sudan. The under-five and crude mortality rates in all IDP sites were below the emergency threshold in week 48. Seven suspect meningitis deaths have been reported from Chotbora PHCC in Longechuk County. The preliminary verification report indicates no new suspect cases since 18 November 2014. Completeness and Timeliness of Reporting Completeness for weekly reporting decreased from 48 (98%) in week 47, to 46 (92%) in week 48. Timeliness for weekly reporting decreased from 35 (72%) in week 47 to 25 (50%) in week 48. -

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War”

South Sudan: Jonglei – “We Have Always Been at War” Africa Report N°221 | 22 December 2014 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Jonglei’s Conflicts Before the Civil War ........................................................................... 3 A. Perpetual Armed Rebellion ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Politics of Inter-Communal Conflict .................................................................. 4 1. The communal is political .................................................................................... 4 2. Mixed messages: Government response to intercommunal violence ................. 7 3. Ethnically-targeted civilian disarmament ........................................................... 8 C. Region over Ethnicity? Shifting Alliances between the Bahr el Ghazal Dinka, Greater Bor Dinka and Nuer ...................................................................................... 9 III. South Sudan’s Civil War in Jonglei .................................................................................. 12 A. Armed Factions in Jonglei ........................................................................................ -

SOUTH SUDAN Consolidated Appeal 2014 - 2016

SOUTH SUDAN Consolidated Appeal 2014 - 2016 UNOCHA Clusters Assess and analyze needs Clusters and HCT Humanitarian Country Monitor, review Team and Coordinator and report Set strategy and priorities HUMANITARIAN PLANNING PROCESS Organizations Clusters Mobilize resources Develop objectives, indicators, and implement response plans and projects OCHA Compile strategy and plans into Strategic Response Plans and CAP 2014-2016 CONSOLIDATED APPEAL FOR SOUTH SUDAN AAR Japan, ACEM, ACF USA, ACT/DCA, ACT/FCA, ACTED, ADESO, ADRA, AHA, AHANI, AMURT International, ARARD, ARC, ARD, ASMP, AVSI, AWODA, BARA, C&D, CAD, CADA, CARE International, Caritas CCR, Caritas DPO-CDTY, CCM, CCOC, CDoT, CESVI, Chr. Aid, CINA, CMA, CMD, CMMB, CORDAID, COSV, CRADA, CRS, CUAMM, CW, DDG, DORD, DRC, DWHH, FAO, FAR, FLDA, GHA, GKADO, GOAL, HCO, HELP e.V., HeRY, HI, HLSS, Hoffnungszeichen, IAS, IMC UK, Intermon Oxfam, INTERSOS, IOM, IRC, IRW, JUH, KHI, LCED, LDA, MaCDA, MAG, MAGNA, Mani Tese, MAYA, MEDAIR, Mercy Corps, MERLIN, MI, Mulrany International, NCDA, NGO Forum, Nile Hope, NPA, NPC, NPP, NRC, OCHA, OSIL, OXFAM GB, PAH, PCO, PCPM, PIN, Plan, PWJ, RedR UK, RI, RUWASSA, SALF, Samaritan's Purse, SC, SCA, SIMAS, SMC, Solidarités, SPEDP, SSUDA, SUFEM, TEARFUND, THESO, TOCH, UDA, UNDSS, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIDO, UNKEA, UNMAS, UNOPS, UNWWA, VSF (Belgium), VSF (Switzerland), WFP, WHO, World Relief, WTI, WV South Sudan, ZOA Refugee Care Please note that appeals are revised regularly. The latest version of this document is available on http://unocha.org/cap. Full project details, continually updated, can be viewed, downloaded and printed from http://fts.unocha.org. Photo caption: Fishermen on the Nile River in South Sudan. -

Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advises the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project, supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state and county levels. The consultation process was led by the Government of South Sudan, with support from the Govern- ment of the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Cover photo: A senior chief from Upper Nile. © UNDP/Sun-ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Upper Nile State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword .......................................................................................................................... -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 Update)

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 update) Three months have elapsed since widespread conflict broke out in South Sudan, and Malakal, Upper Nile’s state capital, remains deserted and largely burned to the ground. The state is patchwork of zones of control, with the rebels holding the largely Nuer south (Longochuk, Maiwut, Nasir, and Ulang counties), and the government retaining the north (Renk), east (Maban and Melut), and the crucial areas around Upper Nile’s oil fields. The rest of the state is contested. The conflict in Upper Nile began as one between different factions within the SPLA but has now broadened to include the targeted ethnic killing of civilians by both sides. With the status of negotiations in Addis Ababa unclear, and the rebel’s 14 March decision to refuse a regional peacekeeping force, conflict in the state shows no sign of ending in the near future. With the first of the seasonal rains now beginning, humanitarian costs of ongoing conflict are likely to be substantial. Conflict began in Upper Nile on 24 December 2013, after a largely Nuer contingent of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLA) 7th division, under the command of General Gathoth Gatkuoth, declared their loyalty to former vice-president Riek Machar and clashed with government troops in Malakal. Fighting continued for three days. The central market was looted and shops set on fire. Clashes also occurred in Tunja (Panyikang county), Wanding (Nasir county), Ulang (Ulang county), and Kokpiet (Baliet county), as the SPLA’s 7th division fragmented, largely along ethnic lines, and clashed among themselves, and with armed civilians. -

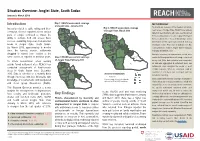

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

South Sudan 2015 Human Rights Report

SOUTH SUDAN 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South Sudan is a republic operating under a transitional constitution signed into law upon declaration of independence from Sudan in 2011. President Salva Kiir Mayardit, whose authority derives from his 2010 election as president of what was then the semiautonomous region of Southern Sudan within the Republic of Sudan, led the country. While the 2010 Sudan-wide elections did not wholly meet international standards, international observers believed Kiir’s election reflected the will of a large majority of Southern Sudanese. International observers considered the 2011 referendum on South Sudanese self-determination, in which 98 percent of voters chose to separate from Sudan, to be free and fair. President Kiir is a founding member of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) political party, the political wing of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). Of the 27 ministries, only 21 had appointed ministers in charge, of which 19 are SPLM representatives. The bicameral legislature consists of 332 seats in the National Legislative Assembly (NLA), of which 296 were filled, and 50 seats in the Council of States. SPLM representatives controlled the vast majority of seats in the legislature. Through presidential decrees Kiir replaced eight of the 10 state governors elected since 2010. The constitution states that an election must be held within 60 days if an elected governor has been relieved by presidential decree. This has not happened. The legislature lacked independence, and the ruling party dominated it. Civilian authorities failed at times to maintain effective control over the security forces. In 2013 armed conflict between government and opposition forces began after violence erupted within the Presidential Guard Force (PG) of the SPLA, also known as the Tiger Division.