World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Covid-19 Weekly Situation

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH (MOH) PUBLIC HEALTHPUBLIC EMERGENCY HEALTH EMERGENCY OPERATIONS OPERATIONS CENTRE (PHEOC) CENTRE (PHEOC) COVID-19 WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Issue NO: 33 Reporting Period: 12-18 October 2020 (week 42) 36,740 2,655 CUMULATIVE SAMPLES TESTED CUMULATIVE RECOVERIES 2,847 CUMULATIVE CONFIRMED CASES 55 9,152 CUMULATIVE DEATHS CUMULATIVE CONTACTS LISTED FOR FOLLOW UP 1. KEY HIGHLIGHTS A cumulative total of 2,847 cases have been confirmed and 55 deaths have been recorded, with case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.9 percent including 196 imported cases as of 18 October 2020. 1 case is currently isolated in health facilities in the Country; and the National IDU has 99% percent bed occupancy available. 2,655 cases (0 new) have been discharged to date. 135 Health Care Workers have been infected since the beginning of the outbreak, with one death. 9,152cumulative contacts have been registered, of which 8,835 have completed the 14-day quarantine. Currently, 317 contacts are being followed, of these 92.1 percent (n=292) contacts were reached. 722 contacts have converted to cases to date; accounting for 25.3 percent of all confirmed cases. Cumulatively 36,740 laboratory tests have been performed with 7.7 percent positivity rate. There is cumulative total of 1,373 alerts of which 86.5 percent (n=1, 187) have been verified and sampled; Most alerts have come from Central Equatorial State (75.1 percent), Eastern Equatoria State (4.4 percent); Upper Nile State (3.2 percent) and the remaining 17.3 percent are from the other States and Administrative Areas. -

The 8Th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan

The 8th African Vaccination Week Report Akobo County, South Sudan Vaccines Work. Do Your Part! Submitted by the CORE Group Polio Project, South Sudan July 2018 INTRODUCTION This report documents efforts of South Sudan’s CORE Group Polio Project (CGPP) during the 8th African Vaccination Week (AVW) held in late April 2018. USAID provides funding for the CGPP’s immunization activities in 11 select counties in South Sudan. The brief highlights the implementation of program activities during AVW for the underserved, marginalized and hard-to-reach populations in Akobo County. From April 23 to April 29, CORE Group South Sudan collaborated with the Universal Network for Knowledge & Empowerment Agency (UNKEA), WHO, UNICEF, Nile Hope, International Medical Corps, and the Akobo County Health Department (CHD) that represents the Republic of South Sudan’s Ministry of Health. The main goal of the annual initiative is to strengthen immunization programs in South Sudan and to draw attention to the right of every child and woman to be protected from vaccine-preventable diseases. The theme for this year’s AVW was “Vaccines work. Do your part!” During the 2018 AVW, CORE Group undertook a variety of activities aimed at raising awareness through advocacy and social mobilization activities to promote the valuable benefits of immunization. These efforts resulted in increased numbers of children and women vaccinated through routine immunization outreach activities in Akobo County. SELECTING AKOBO COUNTY FOR AVW Akobo County is located in northeast South Sudan in Jonglei State and is situated near the international border of the Gambella Region of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia. -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

World Vision South Sudan ECHO FOOD VOUCHER RAPID ASSESSMENT REPORT

1 | P a g e World Vision South Sudan ECHO FOOD VOUCHER RAPID ASSESSMENT REPORT JUNE 2014 By: Bernard D. Togba Jr. Francis Thomas Mogga World Vision South Sudan 2 | P a g e Table of Contents Topic Page List of Tables……………………………………………………………………….………………….. 3 List of Acronyms……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………..……………… 5 2. Objectives……………………………………………………………………………….…………. 6 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………………….………. 6 3.1. Sample………………………………………………………………………………………….7 3.2. Data Management & Analysis………………………………………………………………….. 7 3.3. Limitations……………………………………………………………………………………… 7 4. Overview of Towns…………………………………………………………………………………. 8 4.1. Overview of Malakal…………………………………………………………………………… 8 4.2. Overview of Renk………………………………………………………………………………. 8 4.3. Overview of Kodok…………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4.4. Overview of Lul……………………………………………………………………………….. 10 4.5. Food Availability……………..…………………………………………………………………. 11 5. Summary Results………………………………………………………………………………………11 5.1. Key Informants……………………..……………………………………………………………..11 5.2. Traders…………………………………………………………………………………………….12 5.2.1. Business & Supply………………………………………………………………………. 13 5.2.2. Payment & Transport…………………………….……………………………………. 17 5.3. Beneficiaries………………………………………………………..…………………………….. 19 5.3.1. IDPs Perception…………………………….……..…………………………………… 19 5.3.2. General Characteristics………………………………………………………………….19 5.3.3. Household Welfare & Vulnerability………………………………..…………………… 19 6. Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………………………… 22 World Vision South Sudan 3 | P -

Final Report

THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Ministry of Physical Infrastructure and Rural Development, Upper Nile State THE PROJECT FOR COMPREHENSIVE PLANNING AND SUPPORT FOR URGENT DEVELOPMENT ON SOCIAL ECONOMIC INFRASTRUCTURE IN MALAKAL TOWN IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN FINAL REPORT MAIN TEXT JULY 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL YACHIYO ENGINEERING CO., LTD. EI RECS INTERNATIONAL INC. JR KOKUSAI KOGYO CO., LTD. 14-122 The Project for Comprehensive Planning and Support for Urgent Development on Social Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town in the Republic of South Sudan Project Area Malakal Air Port ✈ Outer Ring Road Ring Road Ring Nile River Nile LBT Road-1 M al ak al Ri ve LB r T Po Ro ad- MoPI&RD 3 LBT Road-1 LEGEND: :Block Boundary :Road :River :Forest :Grassland :Idle Land (Sand and Mud) :Shrub Urgnt Development Support Projects :Water Treatment Plant :Water Pipe :Water Public Tab :Malakal Port :LBT Road PROJECT LOCATION MAP Final Report The Project for Comprehensive Planning and Support for Urgent Development on Social Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town in the Republic of South Sudan Photographs Present Situation of Socio-Economic Infrastructure in Malakal Town 1 Water Treatment Plant of SSUWC Water pipes are detariorated and damaged, (Filter Tank) resulting in high ratio of non-revenue water Malakal Port (Cargo Jetty) Malakal Port (Passenger Jetty) Community Road (Black and Clayey Soil Community roads easily get muddy in rainy called Black Cotton Soil) season. LBT Construction Site (Upper -

Strengthening Free and Independent Media in South Sudan (I-STREAM) Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Progress Report October 2014-Septem

Strengthening Free and Independent Media in South Sudan (i-STREAM) Award No: AID-668-A-13-00005 Fiscal Year 2015 Annual Progress Report October 2014-September 2015 Prepared for: United States Agency for International Development/South Sudan C/O American Embassy Juba, South Sudan Submitted: October 30, 2015 Prepared by: Deborah Ensor Chief of Party Internews in South Sudan PO Box 425, Plot 48 Block 1 Korok The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................... I ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... 2 A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 1 B. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS ............................................................................................................. 2 Eye Media ......................................................................................................................................2 THe Radio Community (TRC) ...........................................................................................................3 Training .........................................................................................................................................4 Humanitarian -

South Sudan Crisis Fact Sheet #44 May 30, 2014

SOUTH SUDAN – CRISIS FACT SHEET #44, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2014 MAY 30, 2014 1 NUMBERS AT USAID/OFDA F U N D I N G HIGHLIGHTS BY SECTOR IN FY 2014 A GLANCE Nearly 900 cholera cases, including 27 deaths, 2% reported in Juba since late April. 3% 5% New UNMISS mandate makes civilian 1,0 40,706 5% 24% protection a priority. Total Number of Individuals Four donors commit 86 percent of the new Displaced in South Sudan 12% since December 15 $618 million in pledges announced at the U.N. Office for the Coordination of humanitarian conference in Oslo, Norway. Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) – May HUMANITARIAN FUNDING 30, 2014 12% 23% TO SOUTH SUDAN TO DATE IN FY 2014 95,000 14% USAID/OFDA $110,000,000 USAID/FFP2 $147,400,000 Total Number of Individuals Water, Sanitation, & Hygiene (24%) 3 Seeking Refuge at U.N. USAID/AFR $14,200,000 Logistics & Relief Supplies (23%) Mission in the Republic of Multi-Sector Rapid Response Fund (14%) 4 State/PRM $73,300,000 South Sudan (UNMISS) Agriculture & Food Security (12%) Compounds Health (12%) $344,900,000 Protection (5%) OCHA – May 30, 2014 Nutrition (5%) TOTAL USAID AND STATE Humanitarian Coordination & Information Management (3%) HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE Economic Recovery and Market Systems (2%) TO SOUTH SUDAN 9 45,706 Total Number of Individuals Displaced in Other Areas of KEY DEVELOPMENTS South Sudan The number of cholera cases in South Sudan continues to steadily increase, with nearly 900 OCHA – May 30, 2014 cases, including 27 cholera-related deaths, reported in Juba, Central Equatoria State, since late April, according to the U.N. -

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 Update)

The Conflict in Upper Nile State (18 March 2014 update) Three months have elapsed since widespread conflict broke out in South Sudan, and Malakal, Upper Nile’s state capital, remains deserted and largely burned to the ground. The state is patchwork of zones of control, with the rebels holding the largely Nuer south (Longochuk, Maiwut, Nasir, and Ulang counties), and the government retaining the north (Renk), east (Maban and Melut), and the crucial areas around Upper Nile’s oil fields. The rest of the state is contested. The conflict in Upper Nile began as one between different factions within the SPLA but has now broadened to include the targeted ethnic killing of civilians by both sides. With the status of negotiations in Addis Ababa unclear, and the rebel’s 14 March decision to refuse a regional peacekeeping force, conflict in the state shows no sign of ending in the near future. With the first of the seasonal rains now beginning, humanitarian costs of ongoing conflict are likely to be substantial. Conflict began in Upper Nile on 24 December 2013, after a largely Nuer contingent of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army’s (SPLA) 7th division, under the command of General Gathoth Gatkuoth, declared their loyalty to former vice-president Riek Machar and clashed with government troops in Malakal. Fighting continued for three days. The central market was looted and shops set on fire. Clashes also occurred in Tunja (Panyikang county), Wanding (Nasir county), Ulang (Ulang county), and Kokpiet (Baliet county), as the SPLA’s 7th division fragmented, largely along ethnic lines, and clashed among themselves, and with armed civilians. -

Security Responses in Jonglei State in the Aftermath of Inter-Ethnic Violence

Security responses in Jonglei State in the aftermath of inter-ethnic violence By Richard B. Rands and Dr. Matthew LeRiche Saferworld February 2012 1 Contents List of acronyms 1. Introduction and key findings 2. The current situation: inter-ethnic conflict in Jonglei 3. Security responses 4. Providing an effective response: the challenges facing the security forces in South Sudan 5. Support from UNMISS and other significant international actors 6. Conclusion List of Acronyms CID Criminal Intelligence Division CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement CRPB Conflict Reduction and Peace Building GHQ General Headquarters GoRSS Government of the Republic of South Sudan ICG International Crisis Group MSF Medecins Sans Frontières MI Military Intelligence NISS National Intelligence and Security Service NSS National Security Service SPLA Sudan People’s Liberation Army SPLM Sudan People’s Liberation Movement SRSG Special Representative of the Secretary General SSP South Sudanese Pounds SSPS South Sudan Police Service SSR Security Sector Reform UNMISS United Nations Mission in South Sudan UYMPDA Upper Nile Youth Mobilization for Peace and Development Agency Acknowledgements This paper was written by Richard B. Rands and Dr Matthew LeRiche. The authors would like to thank Jessica Hayes for her invaluable contribution as research assistant to this paper. The paper was reviewed and edited by Sara Skinner and Hesta Groenewald (Saferworld). Opinions expressed in the paper are those of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of Saferworld. Saferworld is grateful for the funding provided to its South Sudan programme by the UK Department for International Development (DfID) through its South Sudan Peace Fund and the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) through its Global Peace and Security Fund. -

Jonglei State, South Sudan Introduction Key Findings

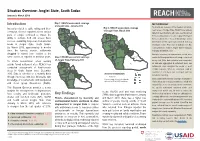

Situation Overview: Jonglei State, South Sudan January to March 2019 Introduction Map 1: REACH assessment coverage METHODOLOGY of Jonglei State, January 2019 To provide an overview of the situation in hard-to- Insecurity related to cattle raiding and inter- Map 3: REACH assessment coverage of Jonglei State, March 2019 reach areas of Jonglei State, REACH uses primary communal violence reported across various data from key informants who have recently arrived parts of Jonglei continued to impact the from, recently visited, or receive regular information ability to cultivate food and access basic Fangak Canal/Pigi from a settlement or “Area of Knowledge” (AoK). services, sustaining large-scale humanitarian Nyirol Information for this report was collected from key needs in Jonglei State, South Sudan. Ayod informants in Bor Protection of Civilians site, Bor By March 2019, approximately 5 months Town and Akobo Town in Jonglei State in January, since the harvest season, settlements February and March 2019. Akobo Duk Uror struggled to extend food rations to the In-depth interviews on humanitarian needs were Twic Pochalla same extent as reported in previous years. Map 2: REACH assessment coverage East conducted throughout the month using a structured of Jonglei State, February 2019 survey tool. After data collection was completed, To inform humanitarian actors working Bor South all data was aggregated at settlement level, and outside formal settlement sites, REACH has Pibor settlements were assigned the modal or most conducted assessments of hard-to-reach credible response. When no consensus could be areas in South Sudan since December found for a settlement, that settlement was not Assessed settlements 2015. -

Bentiu and Malakal Poc Sites’

Conflict Sensitivity Analysis: United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) Protection of Civilian (PoC) Sites Transition: Bentiu, Unity State, and Malakal, Upper Nile State Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility March 2021 This Conflict Sensitivity Analysis (CSA) was requested by the Inter-Cluster Coordination Group in October 2020 and examines the conflict sensitivity implications of the transition of UN Protection of Civilian sites in Bentiu, Unity State, and Malakal, Upper Nile State, from sites under the protection of United Nations Mission in South Sudan to camps for internally displaced persons (IDPs) under the jurisdiction of the Government of the Republic of South Sudan. The Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. The Facility is funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan and is implemented by a consortium of NGOs including Saferworld and swisspeace. Conflict Sensitivity Analysis: Malakal and Bentiu PoC sites Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................................... i 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Overview ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Briefing Paper

BRIEFING PAPER Recommendations for addressing internal displacement and returns in South Sudan INTRODUCTION The study’s findings indicate that POCs provide essen- tial protection for those afraid of being targeted on ethnic Following decades of civil war, a comprehensive peace agree- grounds. This includes IDPs and returning refugees who find ment and the subsequent independence of South Sudan in themselves living in internal displacement once back in the 2011 prompted as many as two million refugees to return to country. Despite the opposition of humanitarian organisations, the world’s youngest country.1 Many, however, were displaced however, the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) again when internal conflict erupted in December 2013. A began to withdraw from the sites in September 2020. temporary reprieve following the signing of a peace agree- ment in 2015 enabled some to return to their homes, but To examine the implications of this withdrawal for the short conflict soon flared up again. and long-term response to internal displacement, IDMC organ- ised an online discussion with partners from the Norwegian A revitalised peace agreement was signed in 2018, but conflict Refugee Council, France’s Agency for Technical Cooperation and violence triggered almost 259,000 new displacements and Development (ACTED) and REACH. the following year.2 A study by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) also found that displaced people Drawing on the outcome of the discussion, this paper calls in South Sudan continue to face barriers in their pursuit of for a comprehensive study of land use to inform discussions durable solutions. Despite the peace agreement, many inter- about return and durable solutions in South Sudan, and nally displaced people (IDPs) and returning refugees remain concerted efforts by all those involved in the response to in Protection of Civilians sites (POCs) because they do not feel promote peaceful coexistence.