Displaced and Immiserated: the Shilluk of Upper Nile in South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Interaction Between International Aid and South Sudanese

Lost in Translation: The interaction between international humanitarian aid and South Sudanese accountability systems September 2020 This research was conducted by the Conflict Sensitivity Resource Facility (CSRF) in August and September 2019 and was funded by the UK, Swiss, Dutch and Canadian donor missions in South Sudan. The CSRF is implemented by a consortium of the NGOs Saferworld and swisspeace. It is intended to support conflict-sensitive aid programming in South Sudan. This research would not have been possible without the South Sudanese and international aid actors who generously gave their time and insights. It is dedicated to the South Sudanese aid workers who tirelessly balance their personal and professional cultures to deliver assistance to those who need it. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology and limitations ........................................................................................................................... -

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017

Situation Overview: Upper Nile State, South Sudan June 2017 SUDAN Introduction previous REACH assessments of hard-to- presence returned to the averages from April reach areas of Upper Nile State. (22% June, 42% May, 28% April).1 This may Despite a potential respite in fighting in lower MANYO be indicative of the slowing of movement due This Situation Overview outlines displacement counties along the western bank, dispersed to the rainy season. Although fighting that took RENK and access to basic services in Upper Nile fighting and widespread displacements trends place in Panyikang and Fashoda appeared to in June 2017. The first section analyses continued into June and impeded the provision subside, clashes between armed groups armed displacement trends in Upper Nile State. of primary needs and access to basic services groups reportedly commenced in Manyo and The second section outlines the population for assessed settlements. Only 45% of assessed Renk Counties, causing the local population to MELUT dynamics in the assessed settlements, as well settlements reported adequate access to food flee across the border as well as to Renk Town.2 and half reported access to healthcare facilities as access to food and basic services for both FASHODA These clashes may have also contributed to across Upper Nile State, while the malnutrition, MABAN IDP and non-displaced communities. MALAKAL a lack of IDPs, with no assessed settlement malaria and cholera concerns reported in May PANYIKANG BALIET Baliet, Maban, Melut and Renk Counties had in Manyo reporting an IDP presence in June, continued into June. LONGOCHUK less than 5% settlement coverage (Map 1), compared to 50% in May. -

The Crisis in South Sudan

Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs September 22, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43344 Conflict in South Sudan and the Challenges Ahead Summary South Sudan, which separated from Sudan in 2011 after almost 40 years of civil war, was drawn into a devastating new conflict in late 2013, when a political dispute that overlapped with preexisting ethnic and political fault lines turned violent. Civilians have been routinely targeted in the conflict, often along ethnic lines, and the warring parties have been accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The war and resulting humanitarian crisis have displaced more than 2.7 million people, including roughly 200,000 who are sheltering at U.N. peacekeeping bases in the country. Over 1 million South Sudanese have fled as refugees to neighboring countries. No reliable death count exists. U.N. agencies report that the humanitarian situation, already dire with over 40% of the population facing life-threatening hunger, is worsening, as continued conflict spurs a sharp increase in food prices. Famine may be on the horizon. Aid workers, among them hundreds of U.S. citizens, are increasingly under threat—South Sudan overtook Afghanistan as the country with the highest reported number of major attacks on humanitarians in 2015. At least 62 aid workers have been killed during the conflict, and U.N. experts warn that threats are increasing in scope and brutality. In August 2015, the international community welcomed a peace agreement signed by the warring parties, but it did not end the conflict. -

Central African Republic (C.A.R.) Appears to Have Been Settled Territory of Chad

Grids & Datums CENTRAL AFRI C AN REPUBLI C by Clifford J. Mugnier, C.P., C.M.S. “The Central African Republic (C.A.R.) appears to have been settled territory of Chad. Two years later the territory of Ubangi-Shari and from at least the 7th century on by overlapping empires, including the the military territory of Chad were merged into a single territory. The Kanem-Bornou, Ouaddai, Baguirmi, and Dafour groups based in Lake colony of Ubangi-Shari - Chad was formed in 1906 with Chad under Chad and the Upper Nile. Later, various sultanates claimed present- a regional commander at Fort-Lamy subordinate to Ubangi-Shari. The day C.A.R., using the entire Oubangui region as a slave reservoir, from commissioner general of French Congo was raised to the status of a which slaves were traded north across the Sahara and to West Africa governor generalship in 1908; and by a decree of January 15, 1910, for export by European traders. Population migration in the 18th and the name of French Equatorial Africa was given to a federation of the 19th centuries brought new migrants into the area, including the Zande, three colonies (Gabon, Middle Congo, and Ubangi-Shari - Chad), each Banda, and M’Baka-Mandjia. In 1875 the Egyptian sultan Rabah of which had its own lieutenant governor. In 1914 Chad was detached governed Upper-Oubangui, which included present-day C.A.R.” (U.S. from the colony of Ubangi-Shari and made a separate territory; full Department of State Background Notes, 2012). colonial status was conferred on Chad in 1920. -

Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014

IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Initial Rapid Needs Assessment: Dethoma, Melut County, Upper Nile State 31 January 2014 This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. 0 IRNA Report: Dethoma, Melut, 31 January 2014 Situation Overview: An ad-hoc IDP camp has been established by the Melut County Commissioner at Dethoma in order to accommodate Dinka IDPs who have fled from Baliet county. Reports of up to 45,000 based in Paloich were initially received by OCHA from RRC and UNMISS staff based in Melut but then subsequent information was received that they had moved to Dethoma. An IRNA mission from Malakal was conducted on 31 January 2014. Due to delays in the deployment by helicopter, the RRC Coordinator was unable to meet the team but we were able to speak to the Deputy Paramount Chief, Chief and a ROSS NGO at the site. The local NGO (Woman Empowerment for Cooperation and Development) had said they had conducted a preliminary registration that showed the presence of 3,075 households. The community leaders said that the camp contained approximately 26,000 individuals. The IRNA team could only visually estimate 5 – 6000 potentially displaced however some may have been absent at the river. The camp is situated on an open field provided and cleared by the Melut County Commissioner, with a river approximately 300metres to the south. There is no cover and as most IDPs had walked to this location, they had carried very minimal NFIs or food. -

South Sudan's

Untapped and Unprepared Dirty Deals Threaten South Sudan’s Mining Sector April 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Invitation to Exploitation 4 Beneath the Battlefield: Mineral Development During Conflict 12 Indications of Possible Money Laundering 19 Recommendations 20 We are grateful for the support we receive from our donors who have helped make our work possible. To learn more about The Sentry’s funders, please visit The Sentry website at www.thesentry.org/about/. UNTAPPED AND UNPREPARED: DIRTY DEALS THREATEN SOUTH SUDAN’S MINING SECTOR TheSentry.org Executive Summary South Sudan’s mining sector has seen rapid development in recent years, and preliminary reports suggest that the industry could become an engine for major economic growth. However, ineffective accountability mechanisms, an opaque corporate landscape, and inadequate due diligence have exposed the sector to abuse by bad actors within South Sudan’s ruling clique. The Sentry has found that existing laws have proven insufficient bulwarks against abuse, raising concerns that the country’s mineral wealth could do little more than spur the kind of violent competition that has ravaged the oil sector. Although South Sudan took welcome steps to reform the mining sector in 2012, some government officials, their relatives, and their close associates have fostered a weak regulatory environment susceptible to exploitation. In one example of how the privileged few have apparently exploited kleptocratic arrangements, President Salva Kiir’s daughter partly owns a company with three active licenses, while another company with three licenses lists former Vice President James Wani Igga’s son as a shareholder. Ashraf Seed Ahmed Hussein Ali, a businessman commonly known as Al-Cardinal who was placed under Global Magnitsky sanctions in October 2019, reportedly owns the company currently holding the greatest number of licenses.1 In the gold-rich region of Kapoeta, state government officials have begun issuing licenses independently of the central government. -

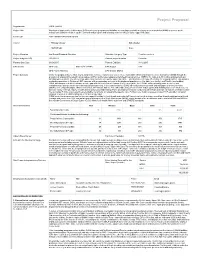

Project Proposal

Project Proposal Organization GOAL (GOAL) Project Title Provision of treatment to children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women diagnosed with moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) or severe acute malnutrition (SAM) for children aged 659 month and pregnant and lactating women in Melut County, Upper Nile State Fund Code SSD15/HSS10/SA2/N/INGO/526 Cluster Primary cluster Sub cluster NUTRITION None Project Allocation 2nd Round Standard Allocation Allocation Category Type Frontline services Project budget in US$ 150,000.01 Planned project duration 5 months Planned Start Date 01/08/2015 Planned End Date 31/12/2015 OPS Details OPS Code SSD15/H/73049/R OPS Budget 0.00 OPS Project Ranking OPS Gender Marker Project Summary Under the proposed intervention, GOAL will provide curative responses to severe acute malnutrition (SAM) and moderate acute malnutrition (MAM) through the provision of outpatient therapeutic programmes (OTPs) and targeted supplementary feeding programmes (TSFPs) for children 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW). The intervention will be targeted to Melut County, Upper Nile State – which has been heavily affected by the ongoing conflict. This includes continuing operations in Dethoma II IDP camp as well as expanding services to the displaced populations in Kor Adar (one facility) and Paloich (two facilities). GOAL also proposes to fill the nutrition service gap in Melut Protection of Civilians (PoC) camp. In the PoC, GOAL will be providing static services, with complementary primary health care and nutrition programming. In the same locations, GOAL will conduct mass outreach and mid upper arm circumference (MUAC) screening campaigns within communities, IDP camps, and the PoC with children aged 659 months and pregnant and lactating women (PLW) in order to increase facility referrals. -

Southern Sudan News Bulletin ______

Southern Sudan News Bulletin ___________________________________________________________________________ An Overview of UN Activities in Southern Sudan Published by the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) _____________________________________________________________________ Vol. 4 Issue No.1 January 2009 Highlights: ¾ Thousands flee LRA attacks ¾ Sudan marks fourth CPA anniversary ¾ Former SPLA combatants turned into Prison Services Wardens ¾ Misseriya still in Southern Kordofan ¾ Planning underway for Tri-State Peace Conference ¾ Data compilation for essential services in Lakes State completed . Sector I – Juba Sudan Marks fourth CPA anniversary Thousands flee LRA attacks On January 9, Sudan marked the fourth Thousands of internally displaced persons anniversary of the Comprehensive Peace (IDPs) and refugees fleeing attacks by Agreement (CPA) that ended 21 years of Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebels have conflict between northern and southern poured into Western Equatoria State, Sudan in the Upper Nile State capital of prompting Governor Jemma Nunu Kumba to Malakal. The ceremony, which was attended launch a humanitarian appeal for by both the President of the Government of assistance. The displacement follows a joint National Unity (GONU), Omar Al Bashir, and military offensive by Ugandan and the First Vice-President of the GONU, Salva Congolese forces against the LRA that was Kiir, drew thousands of Sudanese to the launched on 14 December. The IDPs and city’s stadium. refugees, most of whom come from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), During the celebrations, President Bashir moved into Sudan after LRA attacks on and Vice-President Kiir, who is also their villages killed hundreds and led to the president of the Government of Southern abduction of women, children and even Sudan (GoSS), inaugurated the Malakal men. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

Map of South Sudan

UNITED NATIONS SOUTH SUDAN Geospatial 25°E 30°E 35°E Nyala Ed Renk Damazin Al-Fula Ed Da'ein Kadugli SUDAN Umm Barbit Kaka Paloich Ba 10°N h Junguls r Kodok Āsosa 10°N a Radom l-A Riangnom UPPER NILEBoing rab Abyei Fagwir Malakal Mayom Bentiu Abwong ^! War-Awar Daga Post Malek Kan S Wang ob Wun Rog Fangak at o Gossinga NORTHERN Aweil Kai Kigille Gogrial Nasser Raga BAHR-EL-GHAZAL WARRAP Gumbiel f a r a Waat Leer Z Kuacjok Akop Fathai z e Gambēla Adok r Madeir h UNITY a B Duk Fadiat Deim Zubeir Bisellia Bir Di Akobo WESTERN Wau ETHIOPIA Tonj Atum W JONGLEI BAHR-EL-GHAZAL Wakela h i te LAKES N Kongor CENTRAL Rafili ile Peper Bo River Post Jonglei Pibor Akelo Rumbek mo Akot Yirol Ukwaa O AFRICAN P i Lol b o Bor r Towot REPUBLIC Khogali Pap Boli Malek Mvolo Lowelli Jerbar ^! National capital Obo Tambura Amadi WESTERN Terakeka Administrative capital Li Yubu Lanya EASTERN Town, village EQUATORIAMadreggi o Airport Ezo EQUATORIA 5°N Maridi International boundary ^! Juba Lafon Kapoeta 5°N Undetermined boundary Yambio CENTRAL State (wilayah) boundary EQUATORIA Torit Abyei region Nagishot DEMOCRATIC Roue L. Turkana Main road (L. Rudolf) Railway REPUBLIC OF THE Kajo Yei Opari Lofusa 0 100 200km Keji KENYA o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o 0 50 100mi CONGO o e The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

UNHCR OPERATIONAL UPDATE 01/2017 01-15 January 2017

UNHCR OPERATIONAL UPDATE 01/2017 01-15 January 2017 HIGHLIGHTS KEY FIGURES Maban IDP assessment undertaken after December Unrest: In Maban, UNHCR, and partners Humanitarian Development Consortium (HDC), WFP and South Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Commission (RRC) forged a multi-functional team and INSIDE SOUTH SUDAN conducted a rapid need assessment to the areas hosting IDPs. On the riverbank site, the team identified 1,207 households consisting of 6,053 individuals displaced from two different communities from Doro and Tweji living in the open. The team visited the 262,560 second IDP site Haj Stipta which is hosting 348 households consisting of 1,923 Refugees in South Sudan individuals. Main priority findings included food, NFIs, and shelters. UNHCR extends relief support to vulnerable groups in Upper Nile: In 1.853 M Malakal’s Protection of Civilians site (PoC), UNHCR and its partners Humanitarian Development Consortium (HDC) and Danish Refugee Council (DRC) distributed IDPs in South Sudan, including hygiene kits including soaps and towels to 1,360 Persons with Specific Needs (PSNs). 204,370 people in UNMISS UNHCR and its partners HDC and Samaritan’s Purse also distributed NFIs to 2,464 Protection of Civilians site IDPs, including blankets, plastic sheets, mosquito nest, kitchen sets and sleeping mats for the newly displaced population from Tweji. US $172 million UNHCR distributes Fuel-Efficient Stoves to refugees in Unity: In Ajuong Thok, UNHCR distributed 1,500 Fuel Efficient Stoves (FES) to refugee 730 households. These Funding requested for comprehensive stoves will reduce the frequency of firewood collection thereby enabling refugees to do needs in 2017 other domestic duties.