Unedited Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 World Englishes and their dialect roots Schreier, Daniel Abstract: This chapter investigates the persistence and development of so-called dialect roots, that is, features of local forms of British English that are transplanted to overseas territories. It discusses dialect input and the survival of features, independent developments within overseas communities, including realignments of features in the dialect inputs, as well as contact phenomena when English speakers interact with those of other dialects and languages. The diagnostic value of these roots is exemplified with selected cases from around the world (Newfoundland English, Liberian English, Caribbean Englishes), which are assessed with reference to the archaic/dynamic character of individual features in new-dialect formation and language-contact scenarios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-198161 Book Section Published Version The following work is licensed under a Publisher License. Originally published at: Schreier, Daniel (2020). World Englishes and their dialect roots. In: Schreier, Daniel; Hundt, Marianne; Schneider, Edgar W. The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 384-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots Daniel Schreier World Englishes developed out of English dialects spoken throughout the British Isles. These were transported all over the globe by speakers from different regions, social classes, and educational backgrounds, who migrated with distinct trajectories, for various periods of time and in distinct chronolo- gical phases (Hickey, Chapter 2, this volume; Britain, Chapter 7,thisvolume). -

Dgfs-CNRS Summer School on Linguistic Typology

DGfS-CNRS Summer School on Linguistic Typology Leipzig 15 August–3 September 2010 Creole Languages in a World-Wide Perspective SUSANNE MICHAELIS Max-Planck-Institut für evolutionäre Anthropologie & Universität Gießen Class 2, 24 August 2010 1. Towards a systematic comparison of pidgin and creole language structures • Creole studies have seen various ambitious attempts at explaining the grammatical features of creole languages (substrates, superstrates, and universal principles) • BUT: many of these claims were often based on a relatively small amount of merely suggestive data of only one or a few languages (e.g. Bickerton 1981, Chaudenson 1990); even McWhorter (1998, 2001) does not base his claims on a solid systematic database. 1 Some earlier comparative creole studies, e.g. • Ivens Ferraz (1987) for Portuguese-based creoles • Goodman (1964) for French-based creoles • Hancock (1987) for Atlantic English-based creoles • Baker (1993) for Pacific English-based pidgins/creoles Holm & Patrick (2007), Comparative creole syntax (London: Battlebridge) 2 • the first collaborative project: 18 creole languages are described with respect to a questionnaire of 97 morphosyntactic features • limited to morphosyntax, to 18 languages, and to a book publication without automatic search options • no summarizing tables for all creoles, no synopses • features are Atlantic-biased • some mixing of synchronic and diachronic features, e.g. 8.5 Subordinator from superstrate 'that'; 15.3 Definite article (from superstrate deictic) 2. The APiCS project • large-scale -

Variation and Change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect

VARIATION AND CHANGE IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE TENSE, MODALITY AND ASPECT Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Annaberg sugar mill ruins, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Picture taken by flickr user Navin75. Original in full color. Reproduced and adapted within the freedoms granted by the license terms (CC BY-SA 2.0) applied by the licensor. ISBN: 978-94-6093-235-9 NUR 616 Copyright © 2017: Robbert van Sluijs. All rights reserved. Variation and change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 mei 2017 om 10.30 uur precies door Robbert van Sluijs geboren op 23 januari 1987 te Heerlen Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Copromotor: Dr. M.C. van den Berg (UU) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. R.W.N.M. van Hout Dr. A. Bruyn (Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Den Haag) Prof. dr. F.L.M.P. Hinskens (VU) Prof. dr. S. Kouwenberg (University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica) Prof. dr. C.H.M. Versteegh Part of the research reported in this dissertation was funded by the Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen (KNAW). i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABBREVIATIONS ix 1. VARIATION IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE: TENSE-ASPECT- MODALITY 1 1.1. -

The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages

DigitalResources SIL eBook 25 ® The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages Spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago Using a Comparison of the Markers of Some Key Grammatical Features: A Tool for Determining the Potential to Share and/or Adapt Literary Development Materials David Joseph Holbrook The Classification of the English-Lexifier Creole Languages Spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago Using a Comparison of the Markers of Some Key Grammatical Features: A Tool for Determining the Potential to Share and/or Adapt Literary Development Materials David Joseph Holbrook SIL International ® 2012 SIL e-Books 25 2012 SIL International ® ISBN: 978-1-55671-268-5 ISSN: 1934-2470 Fair-Use Policy: Books published in the SIL e-Books (SILEB) series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes free of charge (within fair-use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s). Series Editor George Huttar Volume Editor Dirk Kievit Managing Editor Bonnie Brown Compositor Margaret González Abstract This study examines the four English-lexifier creole languages spoken in Grenada, Guyana, St. Vincent, and Tobago. These languages are classified using a comparison of some of the markers of key grammatical features identified as being typical of pidgin and creole languages. The classification is based on a scoring system that takes into account the potential problems in translation due to differences in the mapping of semantic notions. -

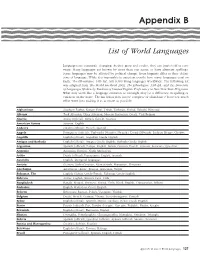

Bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages

Appendix B bbbbbbbbbbbbbbb List of World Languages Languages are constantly changing. As they grow and evolve, they can branch off or con- verge. Many languages are known by more than one name, or have alternate spellings. Some languages may be affected by political change. Even linguists differ in their defini- tions of language. While it is impossible to ascertain exactly how many languages exist on Earth, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., lists 6,809 living languages worldwide. The following list was adapted from The World Factbook 2002, The Ethnologue, 14th Ed., and the Directory of Languages Spoken by Students of Limited English Proficiency in New York State Programs. What may seem like a language omission or oversight may be a difference in spelling or variation on the name. The list below may not be complete or all-inclusive; however, much effort went into making it as accurate as possible. Afghanistan Southern Pashto, Eastern Farsi, Uzbek, Turkmen, Brahui, Balochi, Hazaragi Albania Tosk Albanian, Gheg Albanian, Macedo-Romanian, Greek, Vlax Romani Algeria Arabic (official), French, Kabyle, Chaouia American Samoa Samoan, English Andorra Catalán (official), French, Spanish Angola Portuguese (official), Umbundu, Nyemba, Nyaneka, Loanda-Mbundu, Luchazi, Kongo, Chokwe Anguilla English (official), Anguillan Creole English Antigua and Barbuda English (official), Antigua Creole English, Barbuda Creole English Argentina Spanish (official), Pampa, English, Italian, German, French, Guaraní, Araucano, Quechua Armenia Armenian, Russian, North Azerbaijani -

Tense, Aspect and Modality in Bastimentos

TENSE, ASPECT AND MODALITY IN BASTIMENTOS CREOLE ENGLISH A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Heidi Reid School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Chapter one: Introduction ............................................................................................ 18 1.1 Aims and scope of this thesis ............................................................................... 18 1.2 Framework and general approach ........................................................................ 23 1.2.1 Tense, aspect, modality .................................................................................... 25 1.2.2 Grammaticalisation: Layering & bleaching ..................................................... 27 1.3 TMA markers in BCE .......................................................................................... 29 1.3.1 Position and syntactic distribution ................................................................... 30 1.3.2 TMA combinations .......................................................................................... 31 1.4 Outline of chapters ............................................................................................... 32 2 Chapter two: Creoles .................................................................................................... 34 2.1 A distinct linguistic group? .................................................................................. 34 2.2 The concept of -

2019 Code List

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey 2019 Code List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ANCESTRY CODE LIST 3 FIELD OF DEGREE CODE LIST 25 GROUP QUARTERS CODE LIST 31 HISPANIC ORIGIN CODE LIST 32 INDUSTRY CODE LIST 35 LANGUAGE CODE LIST 45 OCCUPATION CODE LIST 81 PLACE OF BIRTH, MIGRATION, & PLACE OF WORK CODE LIST 96 RACE CODE LIST 106 2 Ancestry Code List ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) 001-099 . ALSATIAN 001 . ANDORRAN 002 . AUSTRIAN 003 . TIROL 004 . BASQUE 005 . FRENCH BASQUE 006 . SPANISH BASQUE 007 . BELGIAN 008 . FLEMISH 009 . WALLOON 010 . BRITISH 011 . BRITISH ISLES 012 . CHANNEL ISLANDER 013 . GIBRALTARIAN 014 . CORNISH 015 . CORSICAN 016 . CYPRIOT 017 . GREEK CYPRIOT 018 . TURKISH CYPRIOT 019 . DANISH 020 . DUTCH 021 . ENGLISH 022 . FAROE ISLANDER 023 . FINNISH 024 . KARELIAN 025 . FRENCH 026 . LORRAINIAN 027 . BRETON 028 . FRISIAN 029 . FRIULIAN 030 . LADIN 031 . GERMAN 032 . BAVARIAN 033 . BERLINER 034 3 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . HAMBURGER 035 . HANNOVER 036 . HESSIAN 037 . LUBECKER 038 . POMERANIAN 039 . PRUSSIAN 040 . SAXON 041 . SUDETENLANDER 042 . WESTPHALIAN 043 . EAST GERMAN 044 . WEST GERMAN 045 . GREEK 046 . CRETAN 047 . CYCLADIC ISLANDER 048 . ICELANDER 049 . IRISH 050 . ITALIAN 051 . TRIESTE 052 . ABRUZZI 053 . APULIAN 054 . BASILICATA 055 . CALABRIAN 056 . AMALFIAN 057 . EMILIA ROMAGNA 058 . ROMAN 059 . LIGURIAN 060 . LOMBARDIAN 061 . MARCHE 062 . MOLISE 063 . NEAPOLITAN 064 . PIEDMONTESE 065 . PUGLIA 066 . SARDINIAN 067 . SICILIAN 068 . TUSCAN 069 4 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . TRENTINO 070 . UMBRIAN 071 . VALLE DAOSTA 072 . VENETIAN 073 . SAN MARINO 074 . LAPP 075 . LIECHTENSTEINER 076 . LUXEMBOURGER 077 . MALTESE 078 . MANX 079 . -

Apics, WALS, and the Creole Typological Profile

APiCS, WALS, and the creole typological profile (if any) Michael Cysouw MPI-EVA Leipzig - LMU München APiCS data so far • 70 languages • 120 features • Multiple values per feature possible • Only 1.4 % missing data! • 46 features comparable to WALS How similar are APiCS languages to each other? Feature 1 Val. 1 Val. 2 Val. 3 Val. 4 Val. 5 Val. 6 African American FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE English Afrikaans TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE How similar are APiCS languages to each other? Feature 1 Val. 1 Val. 2 Val. 3 Val. 4 Val. 5 Val. 6 African American 0 1 0 0 0 0 English Afrikaans 1 1 1 0 0 0 4 agreements out of 6: similarity of 4/6 Feature 1 Val. 1 Val. 2 Val. 3 Val. 4 Val. 5 Val. 6 African American 0 1 0 0 0 0 English Afrikaans 1 1 1 0 0 0 weight agreements by overall frequency (frequent values count less) Feature 1 Val. 1 Val. 2 Val. 3 Val. 4 Val. 5 Val. 6 African American 0 1 0 0 0 0 English Afrikaans 1 1 1 0 0 0 distances from weighted comparison 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 -0.1 distances fromdirect comparison 0.0 0.1 0.2 African American English 0 0.32 0.73 0.51 0.16 0.51 0.27 0.51 0.65 0.46 0.57 0.57 0.49 0.49 0.51 0.59 0.43 0.54 0.46 0.46 0.43 0.65 Afrikaans 0.32 0 0.68 0.73 0.38 0.49 0.46 0.68 0.76 0.62 0.59 0.59 0.54 0.62 0.59 0.7 0.57 0.49 0.51 0.54 0.68 0.76 Ambon Malay 0.73 0.68 0 0.65 0.57 0.3 0.62 0.68 0.59 0.59 0.73 0.62 0.59 0.59 0.57 0.68 0.62 0.59 0.51 0.41 0.62 0.7 Angolar 0.51 0.73 0.65 0 0.49 0.38 0.54 0.43 0.51 0.32 0.54 0.46 0.54 0.65 0.73 0.68 0.43 0.62 0.38 0.46 0.41 0.57 Bahamian Creole 0.16 0.38 0.57 -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/170203 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-02 and may be subject to change. VARIATION AND CHANGE IN VIRGIN ISLANDS DUTCH CREOLE TENSE, MODALITY AND ASPECT Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration: Annaberg sugar mill ruins, St. John, US Virgin Islands. Picture taken by flickr user Navin75. Original in full color. Reproduced and adapted within the freedoms granted by the license terms (CC BY-SA 2.0) applied by the licensor. ISBN: 978-94-6093-235-9 NUR 616 Copyright © 2017: Robbert van Sluijs. All rights reserved. Variation and change in Virgin Islands Dutch Creole Tense, Modality and Aspect Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 11 mei 2017 om 10.30 uur precies door Robbert van Sluijs geboren op 23 januari 1987 te Heerlen Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Copromotor: Dr. M.C. van den Berg (UU) Manuscriptcommissie: Prof. dr. R.W.N.M. van Hout Dr. A. Bruyn (Instituut voor de Nederlandse Taal, Den Haag) Prof. dr. F.L.M.P. Hinskens (VU) Prof. -

Annual Meeting Handbook

MEETING HANDBOOK LINGUISTIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA AMERICAN DIALECT SOCIETY NORTH AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR THE HISTORY OF THE LANGUAGE SCIENCES SOCIETY FOR PIDGIN AND CREOLE LINGUISTICS SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF THE INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES OF THE AMERICAS HILTON ATLANTA AND TOWERS HOTEL ATLANTA, GA 2-5 JANUARY 2003 Introductory Note The LSA Secretariat has prepared this Meeting Handbook to serve as the official program for the 77th Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America (LSA). In addition, this handbook is the official program for the Annual Meetings of the American Dialect Society (ADS), the North American Association for the History of the Language Sciences (NAAHoLS), the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics (SPCL), and the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas (SSILA). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by the LSA Program Committee: (John Whitman, Chair; Chris Barker; Diane Brentari; William Idsardi; Kathleen Ferrara; Catherine Ringen; Margaret Speas; and Rosalind Thornton) and the help of the following members who served as consultants to the Program Committee: Carolyn Temple Adger, Janet Bing, Betty Birner, Aaron Broadwell, Suzanne Flynn, Maya Honda, Philip LeSourd, Ceil Lucas, Amanda Miller-Ockhuizen, Reiko Mazuka, Lise Menn, Miriam Meyerhoff, Richard Rhodes and Satoshi Tomioka. We are also grateful to Tometro Hopkins (SPCL), Michael Mackert (NAAHoLS), Allan Metcalf (ADS), and Victor Golla (SSILA) for their cooperation. We appreciate the help given by the Atlanta Local Arrangements Committee co-chaired by Michael Covington and Mary Zeigler. We hope this Meeting Handbook is a useful guide for those attending, as well as a permanent record of, the 2003 Annual Meeting in Atlanta, GA. -

Caribbean, South and Central America Bettina M Migge

Caribbean, South and Central America Bettina M Migge To cite this version: Bettina M Migge. Caribbean, South and Central America. The Routledge Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Language, Miriam Meyerhoff & Umberto Ansaldo (eds.), 150-178. Malden, MA: Routledge., 2020. hal-03085559 HAL Id: hal-03085559 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03085559 Submitted on 21 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Caribbean, South and Central America Bettina Migge 1. INTRODUCTION The Caribbean, South and Central America are a vast region that has been significantly affected by European colonial expansion. The experience was by no means homogeneous across the region. While the latter two regions were mainly dominated and influenced by Spain and to a lesser extent Portugal (South America), the Caribbean and the Guiana region of South America were subject to expansionist activities from a number of European nations (Denmark, England, France, Netherlands, Spain). Official political dependency on Europe also lasted much longer and still continues in some cases in the Caribbean and the Guiana region while it ended for the most part in the early 19th century in the other two regions. -

Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 Code for Comprehensive Coverage of Languages

© ISO 2003 — All rights reserved ISO TC 37/SC 2 N 292 Date: 2003-08-29 ISO/CD 639-3 ISO TC 37/SC 2/WG 1 Secretariat: ON Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages Codes pour la représentation de noms de langues ― Partie 3: Code alpha-3 pour un traitement exhaustif des langues Warning This document is not an ISO International Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an International Standard. Recipients of this draft are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Document type: International Standard Document subtype: Document stage: (30) Committee Stage Document language: E C:\Documents and Settings\여동희\My Documents\작업파일\ISO\Korea_ISO_TC37\심의문서\심의중문서\SC2\N292_TC37_SC2_639-3 CD1 (E) (2003-08-29).doc STD Version 2.1 ISO/CD 639-3 Copyright notice This ISO document is a working draft or committee draft and is copyright-protected by ISO. While the reproduction of working drafts or committee drafts in any form for use by participants in the ISO standards development process is permitted without prior permission from ISO, neither this document nor any extract from it may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form for any other purpose without prior written permission from ISO. Requests for permission to reproduce this document for the purpose of selling it should be addressed as shown below or to ISO's member body in the country of the requester: [Indicate the full address, telephone number, fax number, telex number, and electronic mail address, as appropriate, of the Copyright Manger of the ISO member body responsible for the secretariat of the TC or SC within the framework of which the working document has been prepared.] Reproduction for sales purposes may be subject to royalty payments or a licensing agreement.