The Sentence of Guadeloupean Creole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish

Perceptions of Dialect Standardness in Puerto Rican Spanish Jonathan Roig Advisor: Jason Shaw Submitted to the faculty of the Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Yale University May 2018 Abstract Dialect perception studies have revealed that speakers tend to have false biases about their own dialect. I tested that claim with Puerto Rican Spanish speakers: do they perceive their dialect as a standard or non-standard one? To test this question, based on the dialect perception work of Niedzielski (1999), I created a survey in which speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish listen to sentences with a phonological phenomenon specific to their dialect, in this case a syllable- final substitution of [R] with [l]. They then must match the sounds they hear in each sentence to one on a six-point continuum spanning from [R] to [l]. One-third of participants are told that they are listening to a Puerto Rican Spanish speaker, one-third that they are listening to a speaker of Standard Spanish, and one-third are told nothing about the speaker. When asked to identify the sounds they hear, will participants choose sounds that are more similar to Puerto Rican Spanish or more similar to the standard variant? I predicted that Puerto Rican Spanish speakers would identify sounds as less standard when told the speaker was Puerto Rican, and more standard when told that the speaker is a Standard Spanish speaker, despite the fact that the speaker is the same Puerto Rican Spanish speaker in all scenarios. Some effect can be found when looking at differences by age and household income, but the results of the main effect were insignificant (p = 0.680) and were therefore inconclusive. -

CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY at the CROSSROADS of SPANISH and ENGLISH in 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO Jackelyn Van Buren Doctoral Student, Linguistics

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-15-2017 CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY AT THE CROSSROADS OF SPANISH AND ENGLISH IN 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO Jackelyn Van Buren Doctoral Student, Linguistics Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Phonetics and Phonology Commons Recommended Citation Van Buren, Jackelyn. "CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY AT THE CROSSROADS OF SPANISH AND ENGLISH IN 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/55 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackelyn Van Buren Candidate Linguistics Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Chris Koops, Chairperson Dr. Naomi Lapidus Shin Dr. Caroline Smith Dr. Damián Vergara Wilson i CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY AT THE CROSSROADS OF SPANISH AND ENGLISH IN 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO by JACKELYN VAN BUREN B.A., Linguistics, University of Utah, 2009 M.A., Linguistics, University of Montana, 2012 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii Acknowledgments A dissertation is not written without the support of a community of peers and loved ones. Now that the journey has come to an end, and I have grown as a human and a scholar and a friend throughout this process (and have gotten married, become an aunt, bought a house, and gone through an existential crisis), I can reflect on the people who have been the foundation for every change I have gone through. -

REFLECTIONS on LIFE: CREOLES, the INTERSECTION of MANY PEOPLES Growing up As Little People, My Siblings and I, As Well As Our Re

REFLECTIONS ON LIFE: CREOLES, THE INTERSECTION OF MANY PEOPLES Growing up as little people, my siblings and I, as well as our relatives, friends and neighbors, sponged up everything around us, unaware that a Creole culture was the atmosphere and environment that we lived, breathed and ingested constantly. It was our father who spoke Cajun, the old French from Canada, and our mother who spoke Creole, the oft-fractured French so dear to all who are part of that culture. A many-splendored culture, it has purloined gems of all kinds from other cultures, in the process of creating its own distinctive jewels unlike any in the world. From rich goodness and talent in every walk of life, we are a flavorful gumbo appetizing to all. With an incredible length and breadth, Creoles span all the color spectrum from deep ebony to dark chocolate to milk chocolate to teasing tan to the ambiguous ivory-complected to sepia to the reddish briqué to high yellow to white. Technically, black is not a color, for it is the absence of visible light. Neither is white a color, for it contains all the wavelengths of visible light. So what is this black/white fuss all about? In any case, most of us are of Afro- Euro-Asian (First American) extraction – quite a bit in addition to what we usually call African American. Seizing upon these broad-based commonalities, confessed Creole Georgina Dhillon from the Seychelles, who later moved to London, had a dream to unite the formidable concentrations of Creoles: Antillean Creole, spoken among 100,000 in Dominica, “The nature isle of the Caribbean”; Antillean Creole, among 100,000 in Grenada; Antillean Creole, among 422,496 in Guadeloupe; French Guiana Creole and Haitian Creole, among 157,277 in French Guiana; Haitian Creole, among 7,000,000 in Haiti; Antillean Creole, among 381,441 in Martinique; Mauritian Creole, among 1,100,000 in Mauritius; Réunion Creole, among 707,758 in Réunion; Antillean Creole, among 150,000 in St. -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure

LINGUISTICS - Pidgins and Creoles - Genevieve Escure PIDGINS AND CREOLES Genevieve Escure Department of English, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, USA Keywords: contact language, lingua franca, (post)creole continuum, basilect, mesolect, acrolect, substrate, superstrate, bioprogram, monogenesis, polygenesis, relexification, variability, code switching, covert prestige, overt prestige, colonization, identity, nativization. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some general properties of pidgins and creoles 3. Pidgins: Incipient communication 3.1. Chinese Pidgin English 3.2. Russenorsk. 3.3. Hawaiian Pidgin English 4. Creoles: Expansion, stabilization and variability 4.1. Basilect 4.2. Acrolect 4.3. Mesolect 5. Theoretical models and current trends in PC studies 5.1. Early models 5.2. Developments of the substratist position 5.3. Developments of the universalist position: The bioprogram 6. The (post)creole continuum and decreolization 7. New trends 7.1. Sociohistorical evidence 7.2. Demographic explanations 7.3. Acquisition 8. Conclusion Acknowledgements Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch UNESCO – EOLSS Summary Pidgins and creolesSAMPLE are languages that arose CHAPTERSin the context of temporary events (e.g., trade, seafaring, and even tourism), or enduring traumatic social situations such as slavery or wars. In the latter context, subjugated people were forced to create new languages for communication. Long stigmatized, those languages provide valuable insight into the mental mechanisms that enable individuals to use their innate capacity -

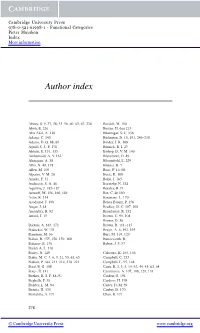

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61998-1 - Functional Categories Pieter Muysken Index More information Author index Abney, S. 9, 37, 38, 53–56, 60–63, 67, 228 Bersick, M. 108 Aboh, E. 226 Besten, H. den 213 Abu-Akel, A. 116 Bhatnagar, S. C. 136 Adams, C. 140 Bickerton, D. 10, 191, 246–250 Adams, D. Q. 88, 89 Binder, J. R. 108 Aguil´oS. J., F. 178 Binnick, R. I. 23 Ahls´en,E. 131, 135 Bishop, D. V. M. 140 Aikhenvald, A. Y. 162 Blakemore, D. 49 Akmajian, A. 58 Bloomfield, L. 229 Alb´o,X. 49, 178 Blutner, R. 7 Allen, M. 109 Boas, F. 14, 60 Alpatov, V. M. 28 Bock, K. 100 Ameka, F. 51 Bolle, J. 163 Anderson, S. A. 46 Boretzky, N. 224 Aquilina, J. 185–187 Borsley, R. D. Aronoff, M. 156, 160, 184 Bot, C. de 150 Aslin, R. 114 Boumans, L. 170 Asodanoe, J. 198 Boyes Braem, P. 156 Auger, J. 48 Bradley, D. C. 107, 108 Austerlitz, R. 92 Broadaway, R. 232 Award, J. 15 Brown, C. 99, 108 Brown, D. 36 Backus, A. 164, 172 Brown, R. 111–115 Badecker, W. 131 Bruyn, A. 6, 192, 193 Baerman, M. 36 Burt, M. 119, 120 Bahan, B. 155, 156, 159, 160 Butterworth, B. Baharav, E. 136 Bybee, J. 3, 57 Bailey A. L. 116 Bailey, N. 120 Calteaux, K. 165, 166 Baker, M. C. 4, 6, 9, 21, 53, 61, 65 Campbell, C. 233 Bakker, P. 184, 211–214, 218–221 Campbell, L. 95, 144 Bard, E. G. -

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California

Chapter 2. Native Languages of West-Central California This chapter discusses the native language spoken at Spanish contact by people who eventually moved to missions within Costanoan language family territories. No area in North America was more crowded with distinct languages and language families than central California at the time of Spanish contact. In the chapter we will examine the information that leads scholars to conclude the following key points: The local tribes of the San Francisco Peninsula spoke San Francisco Bay Costanoan, the native language of the central and southern San Francisco Bay Area and adjacent coastal and mountain areas. San Francisco Bay Costanoan is one of six languages of the Costanoan language family, along with Karkin, Awaswas, Mutsun, Rumsen, and Chalon. The Costanoan language family is itself a branch of the Utian language family, of which Miwokan is the only other branch. The Miwokan languages are Coast Miwok, Lake Miwok, Bay Miwok, Plains Miwok, Northern Sierra Miwok, Central Sierra Miwok, and Southern Sierra Miwok. Other languages spoken by native people who moved to Franciscan missions within Costanoan language family territories were Patwin (a Wintuan Family language), Delta and Northern Valley Yokuts (Yokutsan family languages), Esselen (a language isolate) and Wappo (a Yukian family language). Below, we will first present a history of the study of the native languages within our maximal study area, with emphasis on the Costanoan languages. In succeeding sections, we will talk about the degree to which Costanoan language variation is clinal or abrupt, the amount of difference among dialects necessary to call them different languages, and the relationship of the Costanoan languages to the Miwokan languages within the Utian Family. -

French : the Most Practical Foreign Language

French : The Most Practical Foreign Language While any language will be useful for some jobs or for some regions, French is the only foreign language that can be useful throughout the world as well as in the United States. French as a foreign language is the second most frequently taught language in the world after English. The International Organization of Francophonie has 51 member states and governments. Of these, 28 countries have French as an official language. French is the only language other than English spoken on five continents. French and English are the only two global languages. When deciding on a foreign language for work or school, consider that French is the language that will give you the most choices later on in your studies or your career. French, along with English, is the official working language of ● the United Nations ● UNESCO ● NATO ● Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) ● the International Labor Bureau ● the International Olympic Committee ● the 31-member Council of Europe ● the European Community ● the Universal Postal Union ● the International Red Cross ● Union of International Associations (UIA) French is the dominant working language at ● the European Court of Justice ● the European Tribunal of First Instance ● the European Court of Auditors in Luxembourg. ● the Press Room at the European Commission in Brussels, Belgium One example of the importance of French can be seen in a recent listing of international jobs (8/29/06) distributed by the US State Department: 135 required or preferred French, 49 Spanish, 25 a UN language (Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, and Spanish), 6 Arabic, 6 Russian, 2 German, 2 Italian , and Chinese 2. -

A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 7 Issue 3 Papers from NWAV 29 Article 20 2001 A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos Peter Snow Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Snow, Peter (2001) "A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 , Article 20. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss3/20 A Discrete Co-Systems Approach to Language Variation on the Panamanian Island of Bastimentos 1 Peter Snow 1 Introduction In its ideal form, the phenomenon of the creole continuum as originally described by DeCamp (1971) and Bickerton (1973) may be understood as a result of the process of decreolization that occurs wherever a creole is in direct contact with its lexifier. This contact between creole languages and the languages that provide the majority of their lexicons leads to synchronic variation in the form of a continuum that reflects the unidirectional process of decreolization. The resulting continuum of varieties ranges from the "basilect" (most markedly creole), through intermediate "mesolectal" varie ties (less markedly creole), to the "acrolect" (least markedly creole or the lexifier language itself). -

![A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0716/a-sociophonetic-study-of-the-metropolitan-french-r-linguistic-factors-determining-rhotic-variation-a-senior-honors-thesis-970716.webp)

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation a Senior Honors Thesis

A Sociophonetic Study of the Metropolitan French [R]: Linguistic Factors Determining Rhotic Variation A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Sarah Elyse Little The Ohio State University June 2012 Project Advisor: Professor Rebeka Campos-Astorkiza, Department of Spanish and Portuguese ii ABSTRACT Rhotic consonants are subject to much variation in their production cross-linguistically. The Romance languages provide an excellent example of rhotic variation not only across but also within languages. This study explores rhotic production in French based on acoustic analysis and considerations of different conditioning factors for such variation. Focusing on trills, previous cross-linguistic studies have shown that these rhotic sounds are oftentimes weakened to fricative or approximant realizations. Furthermore, their voicing can also be subject to variation from voiced to voiceless. In line with these observations, descriptions of French show that its uvular rhotic, traditionally a uvular trill, can display all of these realizations across the different dialects. Focusing on Metropolitan French, i.e., the dialect spoken in Paris, Webb (2009) states that approximant realizations are preferred in coda, intervocalic and word-initial positions after resyllabification; fricatives are more common word-initially and in complex onsets; and voiceless realizations are favored before and after voiceless consonants, with voiced productions preferred elsewhere. However, Webb acknowledges that the precise realizations are subject to much variation and the previous observations are not always followed. Taking Webb’s description as a starting point, this study explores the idea that French rhotic production is subject to much variation but that such variation is conditioned by several factors, including internal and external variables. -

Panama's Dollarized Economy Mainly Depends on a Well-Developed Services Sector That Accounts for 80 Percent of GDP

LATIN AMERICAN SOCIO-RELIGIOUS STUDIES PROGRAM - PROGRAMA LATINOAMERICANO DE ESTUDIOS SOCIORRELIGIOSOS (PROLADES) ENCYCLOPEDIA OF RELIGIOUS GROUPS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: RELIGION IN PANAMA SECOND EDITION By Clifton L. Holland, Director of PROLADES Last revised on 3 November 2020 PROLADES Apartado 86-5000, Liberia, Guanacaste, Costa Rica Telephone (506) 8820-7023; E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.prolades.com/ ©2020 Clifton L. Holland, PROLADES 2 CONTENTS Country Summary 5 Status of Religious Affiliation 6 Overview of Panama’s Social and Political Development 7 The Roman Catholic Church 12 The Protestant Movement 17 Other Religions 67 Non-Religious Population 79 Sources 81 3 4 Religion in Panama Country Summary Although the Republic of Panama, which is about the size of South Carolina, is now considered part of the Central American region, until 1903 the territory was a province of Colombia. The Republic of Panama forms the narrowest part of the isthmus and is located between Costa Rica to the west and Colombia to the east. The Caribbean Sea borders the northern coast of Panama, and the Pacific Ocean borders the southern coast. Panama City is the nation’s capital and its largest city with an urban population of 880,691 in 2010, with over 1.5 million in the metropolitan area. The city is located at the Pacific entrance of the Panama Canal , and is the political and administrative center of the country, as well as a hub for banking and commerce. The country has an area of 30,193 square miles (75,417 sq km) and a population of 3,661,868 (2013 census) distributed among 10 provinces (see map below). -

Southern Bahamian: Transported African American Vernacular English Or Transported Gullah?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Southern Bahamian: Transported African American Vernacular English or Transported Gullah? Stephanie Hackert University of Augsberg1 John A. Holm University of Coimbra ABSTRACT The relationship between Bahamian Creole English (BahCE) and Gullah and their historical connection with African American Vernacular English (AAVE) have long been a matter of dispute. In the controversy about the putative creole origins of AAVE, it was long thought that Gullah was the only remnant of a once much more widespread North American Plantation Creole and southern BahCE constituted a diaspora variety of the latter. If, however, as argued in the 1990s, AAVE never was a creole itself, whence the creole nature of southern BahCE? This paper examines the settlement history of the Bahamas and the American South to argue that BahCE and Gullah are indeed closely related, so closely in fact, that southern BahCE must be regarded as a diaspora variety of the latter rather than of AAVE. INTRODUCTION English (AAVE) spoken by the slaves Lexical and syntactic studies of Bahamian brought in by Loyalists after the Creole English (Holm, 1982; Shilling, 1977) Revolutionary War that predominated over led Holm (1983) to conclude that on southern the variety that had developed largely on the Bahamian islands such as Exuma, it was northern Bahamian islands. This ascendancy mainland African American Vernacular developed “…for the simple reason that it had 1 Stephanie Hackert, Applied English Linguistics, University of Augsburg, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] John A. Holm, University of Coimbra, Portugal E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements: An earlier draft of this article benefited from the comments of Katherine Green, Salikoko Mufwene, Edgar Schneider and Donald Winford, whom we would like to thank here, while noting that responsibility for any remaining shortcomings is solely our own.