Fort Charlotte Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notices of the King's Master. Weights of Scotland, With

III. NOTICEE KING'TH F SO S MASTER. WEIGHT F SCOTLANDO S , WITH WRIT THEIF SO R APPOINTMENTS . MYLNEREVS E . R TH . Y B ., M.A., B.C.L. OXON. The King's Master Wright was a personage of less importance than the King's Master Mason or the King's Master of Work. Still, the history of his office resembles in many respects that of the two last- named officials, and we find him and his assistants mentioned from tim e earl timo th et yn ei record f Scotlando s e numbeTh . f wrighto r s in the royal employment seems to have varied considerably, according to e variouth s exigencie e Crownth f d theso s an ; e wrights could readily turn their hands to boat-building, the construction of instruments for military warfare, or the internal fittings of the Eoyal Palace. Some notices of the wrights and carpenters employed by the Kings of Scotlandin early times maybe Exchequerfoune th n di Rolls. Thus 129n ,i 0 Alexander Carpentere th , s wor,hi receiver k fo execute y spa Stirlinn di g Castle by the King's command. In 1361 Malcolm, the Wright, receives £10 fro e fermemth f Aberdeeno s d thian ,s payhien repeates i t laten di r years. Between the years 1362 and 1370 Sir William Dishington acted as Master of Work to the Church of St Monan's in Fife, and received from Kine Th g . alsOd of £613 . o pair 7s Kinm fo d, su ge Davith . II d carpenter's wor t thika s 137churcn I , 7. -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D. -

![The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0899/the-mylne-family-microform-master-masons-architects-engineers-their-professional-career-1481-1876-1410899.webp)

The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876

THE MYLNE FAMILY. MASTER MASONS, ARCHITECTS, ENGINEERS THEIR PROFESSIONAL CAREER 1481-1876. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION BY ROBERT W. MYLNE, C.E., F.R.S., F.S.A., F.G.S., F.S.A Scot PEL, INST. BRIT. ARCH LONDON 187 JOHN MYLNE, MASTER MASON ANDMASTER OF THE LODGE OF SCONE. {area 1640—45.) Jfyotn an original drawing in tliepossession of W. F. Watson, Esq., Edinburgh. C%*l*\ fA^ CONTENTS. PREFACE. " REPRINT FROM ARTICLEIN DICTIONARYOF ARCHITECTURE.^' 1876. REGISTER 07 ABMB—LTONOFFICE—SCOTLAND,1672. BEPBIKT FBOH '-' HISTOBT OF THKLODGE OF EDINBURGH," 1873. CONTRACT BT THE MASTER MASONS OF THE LODGE OF SCONE AND PERTH, 1658. APPENDIX. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE, 1567—1604. CONTRACT WITH GEORGE THOMSON AND JOHN MTLNE, MASONS, TO MAKE ADDITIONS TO LORD BANNTAYNE'S HOUSE AT NEWTTLE. NEAR DUNDEE, 1589. — EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF EDINBURGH, 1616 17. CONTRACT BETWIXT JOHN MTLNE,AND LORD SCONE TO BUILD A CHURCH AT FALKLAND,1620. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE AND ABERDEEN, 1622—27. EXTRACT FROM THE CHAMBEBLAIn'b ACCOUNTS OF THE EABL OF PERTH, 1629. GRANT TOJOHN MTLNEOF THE OFFICE OF PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON TO THEKING,1631. EXTRACTS FBOM THE BUBGH BOOKS OF KIBCALDT AND DUNDEE, 1643—51. GRANT TO JOHN MTLNE, TOUNGER, KING'S PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON> OF THE OFFICE OF CAPTAIN AND MASTER OF PIONEERS AND PRINCIPAL MASTER GUNNER OF ALLSCOTLAND,1646. CONTRACT WITHJOHN MTLNEAND GEORGE 2ND EABL 09 PANMUBE TO BUILDPANMURE HOUSE, ADJACENT TO THE ANCIENT MANSION AT BOWBCHIN, NEAR DUNDEE, 1666. BOTAL WARRANT CONCERNING THE FINISHING OF THE PALACE OF HOLTROOD, 21 FEBRUARY,1676. -

Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise

PMSA NRP: Work Record Ref: EDIN0721 03-Jun-11 © PMSA RAC Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise 773 Carver: Unknown Town or Village Parish Local Govt District County Edinburgh Edinburgh NPA The City of Edinburgh Council Lothian Area in town: Old Town Road: Palace of Holyroodhouse Location: North-west end, between 1st floor windows, of Palace of Holyroodhouse A to Z Ref: OS Ref: Postcode: Previously at: Setting: On building SubType: Public access with entrance fee Commissioned by: Year of Installation: 1906 Details: Design Category: Animal Category: Architectural Category: Commemorative Category: Heraldic Category: Sculptural Class Type: Coat of Arms SubType: Define in freetext of Mary of Guise Subject Non Figurative SubType: Full Length Part(s) of work Material(s) Dimensions > Whole Stone Work is: Extant Listing Status: I Custodian/Owner: Royal Household Condition Report Overall Condition: Good Risk Assessment: No Known Risk Surface Character: Comment No damage Vandalism: Comment None Inscriptions: At base of panel (raised letters): M. R Signatures: None Physical Panel carved in high relief. An eagle with a crown around its neck stands in profile (facing S.) holding a Description: diamond-shaped shield in its left foot. The shield is quartered with a small shield at its centre. Behind the eagle are lilies and below are the initials M. R flanked by fleurs de lis Person or event Mary of Guise commemorated: History of Commission : Exhibitions: Related Works: Legal Precedents: References: J. Gifford, C. McWilliam, D. Walker and C. Wilson, -

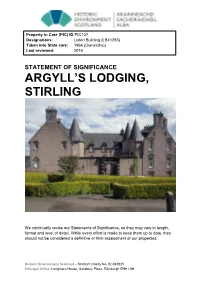

Statement of Significance Argyll’S Lodging, Stirling

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC107 Designations: Listed Building (LB41255) Taken into State care: 1964 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ARGYLL’S LODGING, STIRLING We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 ARGYLL’S LODGING -

Scotland's Royal Palace

Scotland’s royal palace Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh The Scottish Palace of The Queen The surviving interiors of Scotland’s premier royal palace offer a vivid insight into the 17th-century life of the Court. Simon Thurley unravels the history of an outstanding building Photographs by James Brittain f all The Queen’s palaces, that of Holyroodhouse can claim, with Windsor, to be the most venerable. It has its origins in an Augustin- Oian abbey founded in 1128 and is named after its most precious relic—a fragment of the true cross, a piece of the holy rood. Like their English counterparts, medieval Scot- tish kings often preferred to reside in the comfortable lodgings of a rich abbot rather than the austere towers of their own fortresses. More than Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood became a favoured residence of the Scottish kings, and by the reign of James V, the royal lodgings at the abbey overshadowed the monastic parts (Fig 2). Most impressive of the surviving remains from this early palace are the rooms of Mary Queen of Scots (Country Life, November 23, 1995). Like most royal palaces, Holyroodhouse was horribly abused during the Civil War and Commonwealth, and, at the Restoration, it was very run down. The Scottish Privy Council had a scheme for smartening it up in 1661, but, in 1670, it was decided to almost completely rebuild it. What was constructed between 1671 and 1679 was no normal palace. At the time, it seemed very unlikely that Charles II would ever visit Edinburgh, let The Royal Collection alone live there. The royal apartments were ➢ Fig 1: The King’s Bedchamber with its 1680s state bed. -

The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House Citation for published version: Nicholas Uglow, Tom, Addyman & Lowrey, J 2012, 'The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House: Leslie House and Kinross House', Architectural Heritage, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 163-178. https://doi.org/10.3366/arch.2012.0038 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/arch.2012.0038 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Architectural Heritage Publisher Rights Statement: © The Architectural Heritage Society, 2012. Tom, Addyman, Lowrey, J., & Nicholas Uglow (2013). The archaeology and conservation of the country house: Leslie House and Kinross House. Architectural Heritage, 23(1), 163-178doi: 10.3366/arch.2012.0038 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Nicholas Uglow, Tom Addyman and John Lowrey The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House: Leslie House and Kinross House Between 2010 and 2012, the authors worked on Leslie House, Fife, and Kinross House, Perth & Kinross, both by Sir William Bruce. -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

The Ancient Sundials of Scotland Andrew R Somerville*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 117 (1987), 233-264, fiche 3: A2-G14 The ancient sundials of Scotland Andrew R Somerville* SUMMARY Scotland has a rich heritage of Renaissance' sundials which are more numerous than in any other country. These are free-standing stone sculptures dating from the 17th and early 18th centuries, with many dials inscribed on them, often in shapes which may have symbolic significance. A catalogue has been prepared including those which have been recorded in the past and have now disappeared, as well as those which still survive. The various types are described and comparisons made with those in other countries, showing the unique character of the Scottish style. The reasons for their appearance in Scotland at this time are first of all material: more stable government and increased prosperity led to the building of mansion houses with pleasure gardens. Secondly, the Calvinist philosophy of the time frowned on decoration for its own sake and required function as well. Thirdly, interest in science was increasing, along with the Renaissance interest in re-discovering the esoteric knowledge of the ancients. In addition, freemasonry may have had its beginnings in Scotland in the late 16th century and certainly assumed considerable importance in the 17th; this is unlikely to be mere coincidence and the dials probably had a significance which went well beyond simple time-keeping. The main listing of the catalogue is given in microfiche form, but summaries are printed. CONTENTS PRINTED SECTION Introduction ............... 234 Description of the dials ............. 235 History and continental influences ........... 246 Symbolism ............... 251 Conclusions ............... 254 The Catalogue ............. -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for February 22Nd, 2019

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for February 22nd, 2019 To see what we've added to the Electric Scotland site view our What's New page at: http://www.electricscotland.com/whatsnew.htm To see what we've added to the Electric Canadian site view our What's New page at: http://www.electriccanadian.com/whatsnew.htm For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: https://electricscotland.com/scotnews.htm Electric Scotland News We've just come off the long weekend here in Canada entitled "Family Day". Not sure if this is a day celebrated anywhere else in the world but a nice sentiment for sure. You'll not in the news that the "Big Yin' (Billy Connolly) has been selected as the Parade Marshall for the Tartan Day Parade in NYC in April. ------- You can view a video introduction to this newsletter at: https://youtu.be/4Oo60ick2EQ Scottish News from this weeks newspapers Note that this is a selection and more can be read in our ScotNews feed on our index page where we list news from the past 1-2 weeks. I am partly doing this to build an archive of modern news from and about Scotland as all the newsletters are archived and also indexed on Google and other search engines. I might also add that in newspapers such as the Guardian, Scotsman, Courier, etc. you will find many comments which can be just as interesting as the news story itself and of course you can also add your own comments if you wish. -

Notices of the King's Master-Gunners of Scotland, with the Writ Theif So R Appointments, 1512-1703

V. NOTICES OF THE KING'S MASTER-GUNNERS OF SCOTLAND, WITH THE WRIT THEIF SO R APPOINTMENTS, 1512-1703. BY . MYLNEREVS . R . , M.A., B.O.L. OXON. e offic f King'Th o e s Master Gunne a publi s wa cr positio f varyino n g importance accordin tho gt e politica militard an l y exigencie f tho se time. When there was war with England, or civil war prevailed at home, and the whole country was torn and rent with internal divisions, then the Master Gunner becam evera y prominen te safet e kingdopersoth th r f yo fo n: m for the time being seemed at all events placed in his all-powerful hands. dayn I prolongef so d peace, however generalle ,h y sank into insignificance. At first the Master Gunner was usually appointed to the charge of the artillery and guns in some particular castle. Afterwards, when numerous appointments of this kind had been made, a Principal Mastsr Gunner was selected to'superintend the other officials in this department of the service of the Crown. e MasteTh r Gunne s alswa or sometimes give e appointmenth n f o t Master Wright. Sometime hele sh office d th f armourer o e somr o , e other kindred office. From the Exchequer Rolls we learn that Robert Borthuik was the 186 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, FEBRUARY 13, 1899. principal Master Gunnee s thaKinth wa tn 1512f g i o yead r n an i ,r Dieppe on the King's business, doubtless making active preparation for campaige th n which terminate e disastrouth n di s battl Floddenf o e n I . -

Notice of Some Stone Crosses, with Especial Reference to E Market-Crosseth Scotlandf So Jamey B

II. NOTICE OF SOME STONE CROSSES, WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE TO E MARKET-CROSSETH SCOTLANDF SO JAMEY B . S DRUMMOND, ESQ., R.S.A., F.S.A. SCOT. .Fro e interesmth t lately createe proposeth y b d d restoratioe th f no ancient City Cross of Edinburgh, it occurred to me that, having at various times made sketches of a number of Scottish market-crosses, a notice of thesf o w e afe migh acceptable b t thio et s Society. In addition to Market or Town Crosses, there are two other kinds of Crosses that may be mentioned, viz., Ecclesiastical and Memorial. Of e latterth e havw , a greae t man n Scotlandi y . .For illustrationa f o s highly-interesting clas thesef so deepublie a e th ,p ow cdeb gratitudf o t e to the Spalding Clu their bfo r beautiful volum "e Standinth n eo g Stones of Scotland," so well edited by their and our secretary, Mr Stuart. There is, however, a class not included in this volume to which I will simply allude, such as the one on the Hawkhill, near Alloa, having merel rudya e cross carve n eaco d h side (fig . Thi2) . e s th seem e b o st first step in advance from the rude upright monolith, marking the site t Dunbaobattle—suca a f e on re (figth s ha . 1)—o grave chiefa th r f eo . By the wayside, near Finzean House, Aberdeenshire, stands one stated by tradition to be erected to the memory of Dardanus, one of our mythic Scottish kings; wooe whilth cairn— s dn e i hi closs i y eb a very large one, ANTIQUARIE SCOTLANDF SO .