Scotland's Royal Palace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notices of the King's Master. Weights of Scotland, With

III. NOTICEE KING'TH F SO S MASTER. WEIGHT F SCOTLANDO S , WITH WRIT THEIF SO R APPOINTMENTS . MYLNEREVS E . R TH . Y B ., M.A., B.C.L. OXON. The King's Master Wright was a personage of less importance than the King's Master Mason or the King's Master of Work. Still, the history of his office resembles in many respects that of the two last- named officials, and we find him and his assistants mentioned from tim e earl timo th et yn ei record f Scotlando s e numbeTh . f wrighto r s in the royal employment seems to have varied considerably, according to e variouth s exigencie e Crownth f d theso s an ; e wrights could readily turn their hands to boat-building, the construction of instruments for military warfare, or the internal fittings of the Eoyal Palace. Some notices of the wrights and carpenters employed by the Kings of Scotlandin early times maybe Exchequerfoune th n di Rolls. Thus 129n ,i 0 Alexander Carpentere th , s wor,hi receiver k fo execute y spa Stirlinn di g Castle by the King's command. In 1361 Malcolm, the Wright, receives £10 fro e fermemth f Aberdeeno s d thian ,s payhien repeates i t laten di r years. Between the years 1362 and 1370 Sir William Dishington acted as Master of Work to the Church of St Monan's in Fife, and received from Kine Th g . alsOd of £613 . o pair 7s Kinm fo d, su ge Davith . II d carpenter's wor t thika s 137churcn I , 7. -

A Rough Sketch of the History of Stained Glass

MEDIAEVAL STAINED GLASS FROM HOLYROOD ABBEY CHURCH. 81 IV. MEDIAEVAL STAINED GLASS RECENTLY RECOVERED PROE MTH . RUIN F HOLYROOO S D ABBE Y. EELESC CHURCH . P , Y B . P.S.A. SCOT. The fragment f mediaevao s l stained glass e describeaboub o t t d were found on the top of the vaulting of the south aisle of the nave of Holyrood Abbey Church during repairs to the roof in 1909. They have since been ^carefully cleaned and set up to form part of a window e picturth f o e e eas d galleryth en t t a . Their discover f first-claso s yi s importanc o Scottist e h ecclesiastical archaeology, because [hardly yan stained glas s surviveha s d from mediaeval Scotland. ROUGA H SKETCHISTORE TH F STAINEHF O Y O D GLASS. Before describing the Holyrood glass in detail, it will perhaps be n over ru s wel a ,o t lver y briefly e historth , d developmenan y f o t mediaeval stained glass, as a glance at the main points may make t easiei realiso t r exace eth t positio relatiod nan e newl th f no y recovered Holyrood fragments. The ornamentatio f glasno s vessel meany b s f colouso s practisewa r d e Romanbyth s wel a ss othea l r ancient e decorationationsth d an , n oa largf e surfac meany eb numbea f o s f pieceo r f coloureso d glasr o s glazed material carefully fitted together was also well known, but the principlt applieno s windowso dt wa e , althoug e glazinhth f windowgo s with plain glas s knowe Romansth wa s o nt r windofo , w glas founs i s d in almost every Roman fort. -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D. -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

![The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0899/the-mylne-family-microform-master-masons-architects-engineers-their-professional-career-1481-1876-1410899.webp)

The Mylne Family [Microform] : Master Masons, Architects, Engineers, Their Professional Career, 1481-1876

THE MYLNE FAMILY. MASTER MASONS, ARCHITECTS, ENGINEERS THEIR PROFESSIONAL CAREER 1481-1876. PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION BY ROBERT W. MYLNE, C.E., F.R.S., F.S.A., F.G.S., F.S.A Scot PEL, INST. BRIT. ARCH LONDON 187 JOHN MYLNE, MASTER MASON ANDMASTER OF THE LODGE OF SCONE. {area 1640—45.) Jfyotn an original drawing in tliepossession of W. F. Watson, Esq., Edinburgh. C%*l*\ fA^ CONTENTS. PREFACE. " REPRINT FROM ARTICLEIN DICTIONARYOF ARCHITECTURE.^' 1876. REGISTER 07 ABMB—LTONOFFICE—SCOTLAND,1672. BEPBIKT FBOH '-' HISTOBT OF THKLODGE OF EDINBURGH," 1873. CONTRACT BT THE MASTER MASONS OF THE LODGE OF SCONE AND PERTH, 1658. APPENDIX. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE, 1567—1604. CONTRACT WITH GEORGE THOMSON AND JOHN MTLNE, MASONS, TO MAKE ADDITIONS TO LORD BANNTAYNE'S HOUSE AT NEWTTLE. NEAR DUNDEE, 1589. — EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF EDINBURGH, 1616 17. CONTRACT BETWIXT JOHN MTLNE,AND LORD SCONE TO BUILD A CHURCH AT FALKLAND,1620. EXTRACTS FROM THE BURGH BOOKS OF DUNDEE AND ABERDEEN, 1622—27. EXTRACT FROM THE CHAMBEBLAIn'b ACCOUNTS OF THE EABL OF PERTH, 1629. GRANT TOJOHN MTLNEOF THE OFFICE OF PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON TO THEKING,1631. EXTRACTS FBOM THE BUBGH BOOKS OF KIBCALDT AND DUNDEE, 1643—51. GRANT TO JOHN MTLNE, TOUNGER, KING'S PRINCIPAL MASTER MASON> OF THE OFFICE OF CAPTAIN AND MASTER OF PIONEERS AND PRINCIPAL MASTER GUNNER OF ALLSCOTLAND,1646. CONTRACT WITHJOHN MTLNEAND GEORGE 2ND EABL 09 PANMUBE TO BUILDPANMURE HOUSE, ADJACENT TO THE ANCIENT MANSION AT BOWBCHIN, NEAR DUNDEE, 1666. BOTAL WARRANT CONCERNING THE FINISHING OF THE PALACE OF HOLTROOD, 21 FEBRUARY,1676. -

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise

PMSA NRP: Work Record Ref: EDIN0721 03-Jun-11 © PMSA RAC Panel Carved with the Arms of Mary of Guise 773 Carver: Unknown Town or Village Parish Local Govt District County Edinburgh Edinburgh NPA The City of Edinburgh Council Lothian Area in town: Old Town Road: Palace of Holyroodhouse Location: North-west end, between 1st floor windows, of Palace of Holyroodhouse A to Z Ref: OS Ref: Postcode: Previously at: Setting: On building SubType: Public access with entrance fee Commissioned by: Year of Installation: 1906 Details: Design Category: Animal Category: Architectural Category: Commemorative Category: Heraldic Category: Sculptural Class Type: Coat of Arms SubType: Define in freetext of Mary of Guise Subject Non Figurative SubType: Full Length Part(s) of work Material(s) Dimensions > Whole Stone Work is: Extant Listing Status: I Custodian/Owner: Royal Household Condition Report Overall Condition: Good Risk Assessment: No Known Risk Surface Character: Comment No damage Vandalism: Comment None Inscriptions: At base of panel (raised letters): M. R Signatures: None Physical Panel carved in high relief. An eagle with a crown around its neck stands in profile (facing S.) holding a Description: diamond-shaped shield in its left foot. The shield is quartered with a small shield at its centre. Behind the eagle are lilies and below are the initials M. R flanked by fleurs de lis Person or event Mary of Guise commemorated: History of Commission : Exhibitions: Related Works: Legal Precedents: References: J. Gifford, C. McWilliam, D. Walker and C. Wilson, -

Statement of Significance Argyll’S Lodging, Stirling

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC107 Designations: Listed Building (LB41255) Taken into State care: 1964 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ARGYLL’S LODGING, STIRLING We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH 1 ARGYLL’S LODGING -

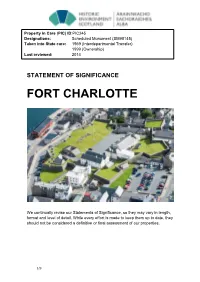

Fort Charlotte Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC245 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90145) Taken into State care: 1969 (Interdepartmental Transfer) 1999 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE FORT CHARLOTTE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. 1/9 © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot 2/9 FORT CHARLOTTE SYNOPSIS Fort Charlotte is located in the centre of Lerwick, sandwiched between Charlotte Street (south), Market Street (west), Harbour Street (north) and the Esplanade (east), and overlooking the Bressay Sound. Next to Fort George, it is the most complete trace Italienne (angle-bastioned) artillery fortification in Scotland. The fort originated during the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665-7), when it was built to protect the naval anchorage in Bressay Sound. -

The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House

Edinburgh Research Explorer The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House Citation for published version: Nicholas Uglow, Tom, Addyman & Lowrey, J 2012, 'The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House: Leslie House and Kinross House', Architectural Heritage, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 163-178. https://doi.org/10.3366/arch.2012.0038 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.3366/arch.2012.0038 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Architectural Heritage Publisher Rights Statement: © The Architectural Heritage Society, 2012. Tom, Addyman, Lowrey, J., & Nicholas Uglow (2013). The archaeology and conservation of the country house: Leslie House and Kinross House. Architectural Heritage, 23(1), 163-178doi: 10.3366/arch.2012.0038 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Nicholas Uglow, Tom Addyman and John Lowrey The Archaeology and Conservation of the Country House: Leslie House and Kinross House Between 2010 and 2012, the authors worked on Leslie House, Fife, and Kinross House, Perth & Kinross, both by Sir William Bruce. -

The Coronation Stone Was Read by the Author, As Senior Vice-President of the Society of Anti- Quaries of Scotland, at a Meeting of the Society Held on the 8Th Of

I ^ II t llll' 'X THE COEONATION STONE Privted by R. Clark, EDMONSTON S: DOUGLAS, EDINRURGH. LONDON HAMILTON, AnA^L';, AMD CO. Clje Coronation g>tone WILLIAM F. SKENE ':<©^=-f#?2l^ EDINBURGH : EDMONSTON & DOUGLAS MDCCCLXIX. — . PREFATORY NOTE. This analysis of the legends connected with the Coronation Stone was read by the author, as Senior Vice-President of the Society of Anti- quaries of Scotland, at a Meeting of the Society held on the 8th of March last. A limited impression is now published with Notes and Illus- trations. The latter consist of I. The Coronation Chair, with the stone under the seat, as it is at present seen in Westminster Abbey, im the rover. II. The reverse of the Seal of the Abbey of Scone, showing the Scottish King seated in the Eoyal Chair, on the title-page. III. Ancient Scone, as i-epresented in the year 1693 in Slezer's Theatntm Scofim, to precede page 1 a. Chantorgait. h. Friar's Den. c. Site of Abbey. d. Palace. e. Moot Hill, with the Church built in 1624 upon it. /'. The river Tay. IV. The Coronation Chair as shewn by HoUinshed in 1577, ptoge 12. V. Coronation of Alexander III., from the MS. of Fordun, con- tained in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. This is a MS. of the Scoticronicon, as altered, interpolated, and continued by Bower, ojyposite Latin description in the Appendix, page 47. 20 Inverleith Kow, Edinbukgh, 7/// Jan,' 1869. The Prospect of the Horn a. Chantorcjait. i. SlTK OF AliKEV. /'. Fkiak's Dkn. ./. Pai.ack. -

'In Me Porto Crucem': a New Light on the Lost St Margaret's Crux Nigra

© The Author(s) 2020. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ‘In me porto crucem’: a new light on the lost St Margaret’s crux nigra Francesco Marzella Abstract St Margaret of Scotland owned a reliquary containing a relic of the True Cross known as crux nigra. Both Turgot, Margaret’s biographer, and Aelred of Rievaulx, who spent some years at the court of Margaret’s son, King David, mention the reliquary without offering sufficient information on its origin. The Black Rood was probably lost or destroyed in the sixteenth century. Some lines written on the margins of a twelfth- century manuscript containing Aelred’s Genealogia regum Anglorum can now shed a new light on this sacred object. The mysterious lines, originally written on the Black Rood or more probably on the casket in which it was contained, claim that the relic once belonged to an Anglo-Saxon king, and at the same time they seem to convey a signifi- cant political message. In his biography of St Margaret of Scotland,1 Turgot († 1115),2 at the time prior of Durham, mentioned an object that was particularly dear to the queen. It was a cross known as crux nigra. In chapter XIII of his Vita sanctae Margaretae, Turgot tells how the queen wanted to see it for the last time when she felt death was imminent: 3 Ipsa quoque illam, quam Nigram Crucem nominare, quamque in maxima semper ven- eratione habere consuevit, sibi afferri præcepit.