Scottish Nationalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

Postmodernism: the American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document

Postmodernism: The American T.V. Show, 'Family Guy, As a Politically Incorrect Document Tyron Tyson Smith1; Ajit Duara2* 1Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*Symbiosis Institute of Media and Communication, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, Maharashtra, India. 2*[email protected] Abstract Postmodernism is a movement that grew out of modernism. Movements in art, literature, and cinema focused on a particular stance. The visual artists who created entertainment focused on expressing the creator herself/himself beginning from German expressionism to modernism, surrealism, cubism, etc. These art movements played an important part in what an artist (literature, art, and visual) portrayed to his or her audience. As perspectives played an important part, an understanding of what the artist needed to portray was critical. Modernism dealt with this portrayal, which came about due to the changes taking place in society. In terms of the industry, where the overall product dealt with features like individualism, experimentation and absurdity, modernism dealt with a need to overthrow past notions of what painting, literature, and the visual arts needed to be. "After World War II, the focus moved from Europe to the United States, and abstract expressionism (led by Jackson Pollock) continued the movement's momentum, followed by movements such as geometric abstractions, minimalism, process art, pop art, and pop music." Postmodernism helped do away with these shortcomings. An understanding of postmodernism is explored in this paper. The main point which sets it apart is concepts like pastiche, intersexuality, and spectacle. Concerning pop culture, an understanding of referencing is a constant trait used by postmodern art. -

Business Banking Service Quality - Great Britain

Business banking service quality - Great Britain Independent service quality survey results Business current accounts Published August 2019 As part of a regulatory requirement, an independent survey was conducted to ask customers of the 14 largest business current account providers if they would recommend their provider to other small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs*). The results represent the view of customers who took part in the survey. These results are from an independent survey carried out between July 2018 and June 2019 by BVA BDRC as part of a regulatory requirement, and we have published this information at the request of the providers and the Competition and Markets Authority so you can compare the quality of service from business current account providers. In providing this information, we are not giving you any advice or making any recommendation to you. SME customers with business current accounts were asked how likely they would be to recommend their provider, their provider’s online and mobile banking services, services in branches and business centres, SME overdraft and loan services and relationship/account management services to other SMEs. The results show the proportion of customers of each provider who said they were ’extremely likely’ or ‘very likely’ to recommend each service. Participating providers: Allied Irish Bank (GB), Bank of Scotland, Barclays, Clydesdale Bank, Handelsbanken, HSBC UK, Lloyds Bank, Metro Bank, NatWest, Royal Bank of Scotland, Santander UK, The Co-operative Bank, TSB, Yorkshire Bank. Approximately 1,200 customers a year are surveyed across Great Britain for each provider; results are only published where at least 100 customers have provided an eligible score for that service in the survey period. -

Trilingualism and National Identity in England, from the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 2015 Three Languages, One Nation: Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century Christopher Anderson Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, Christopher, "Three Languages, One Nation: Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century" (2015). WWU Graduate School Collection. 449. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/449 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Three Languages, One Nation Trilingualism and National Identity in England, From the Mid-Twelfth to the Early Fourteenth Century By Christopher Anderson Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kathleen L. Kitto, Dean of the Graduate School Advisory Committee Chair, Dr. Peter Diehl Dr. Amanda Eurich Dr. Sean Murphy Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

The Future of the UK

The Future of the UK Between Internal and External Divisions Edited by Marius Guderjan Imprint © 2016 Editor: Marius Guderjan Individual chapters in order © Marius Guderjan, Pauline Schnapper, Sandra Schwindenhammer, Neil McGarvey and Fraser Stewart, Paul Cairney, Paul Carmichael and Arjan Schakel. Centre for British Studies Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin www.gbz.hu-berlin.de Design: Sandra van Lente Cover: Marius Guderjan Cover picture: www.shutterstock.com A printed version of this ebook is available upon request. Printed by WESTKREUZ-DRUCKEREI AHRENS KG Berlin www.westkreuz.de Funded by the Future Concept resources of Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin through the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal Government and its Federal States. The Future of the UK Between Internal and External Divisions Edited by Marius Guderjan Contents Foreword 4 Notes on Contributors 6 1. Between Internal and External Divisions 9 Marius Guderjan 2. The EU Referendum and the Crisis of British Democracy 31 Pauline Schnapper 3. Loose but not Lost! Four Challenges for the EU in the 42 Aftermath of the British Referendum Sandra Schwindenhammer 4. European, not British? Scottish Nationalism and the EU 59 Referendum Neil McGarvey and Fraser Stewart 5. The Future of Scotland in the UK: Does the Remarkable 71 Popularity of the SNP Make Independence Inevitable? Paul Cairney 6. Reflections from Northern Ireland on the Result of the 82 UK Referendum on EU Membership Paul Carmichael 7. Moving Towards a Dissolved or Strengthened Union? 102 Arjan H. Schakel 3 Foreword In the light of the British referendum on EU membership on 23 June, the Centre for British Studies of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin organised a series of public lectures on the future of the UK during the summer term 2016. -

The Height of Its Womanhood': Women and Genderin Welsh Nationalism, 1847-1945

'The height of its womanhood': Women and genderin Welsh nationalism, 1847-1945 Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kreider, Jodie Alysa Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 04:59:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/280621 'THE HEIGHT OF ITS WOMANHOOD': WOMEN AND GENDER IN WELSH NATIONALISM, 1847-1945 by Jodie Alysa Kreider Copyright © Jodie Alysa Kreider 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY In Partia' Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3145085 Copyright 2004 by Kreider, Jodie Alysa All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3145085 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

Teaching the Voices of History Through Primary Sources and Historical Fiction: a Case Study of Teacher and Librarian Roles

Syracuse University SURFACE School of Information Studies - Dissertations School of Information Studies (iSchool) 2011 Teaching the Voices of History Through Primary Sources and Historical Fiction: A Case Study of Teacher and Librarian Roles Barbara K. Stripling Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/it_etd Recommended Citation Stripling, Barbara K., "Teaching the Voices of History Through Primary Sources and Historical Fiction: A Case Study of Teacher and Librarian Roles" (2011). School of Information Studies - Dissertations. 66. https://surface.syr.edu/it_etd/66 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information Studies (iSchool) at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Information Studies - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT The ability to analyze alternative points of view and to empathize (understand the beliefs, attitudes and actions of another from the other’s perspective rather than from one’s own) are essential building blocks for learning in the 21 st century. Empathy for the human participants of historical times has been deemed by a number of educators as important for the development of historical understanding. The classroom teacher and the school librarian both have a prominent stake in creating educational experiences that foster the development of perspective, empathy, and understanding. This case study was designed to investigate the idea -

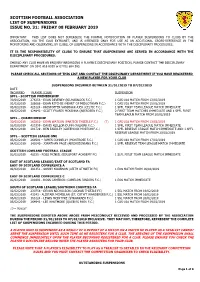

Scottish Football Association List of Suspensions Issue No

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIST OF SUSPENSIONS ISSUE NO. 31: FRIDAY 08 FEBRUARY 2019 IMPORTANT – THIS LIST DOES NOT SUPERSEDE THE FORMAL NOTIFICATION OF PLAYER SUSPENSIONS TO CLUBS BY THE ASSOCIATION, VIA THE CLUB EXTRANET, AND IS INTENDED ONLY FOR USE AS AN ADDITIONAL CROSS-REFERENCE IN THE MONITORING AND OBSERVING, BY CLUBS, OF SUSPENSIONS IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. IT IS THE RESPONSIBILITY OF CLUBS TO ENSURE THAT SUSPENSIONS ARE SERVED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DISCIPLINARY PROCEDURES. SHOULD ANY CLUB HAVE AN ENQUIRY REGARDING A PLAYER’S DISCIPLINARY POSITION, PLEASE CONTACT THE DISCIPLINARY DEPARTMENT ON 0141 616 6018 or 07702 864 165. PLEASE CHECK ALL SECTIONS OF THIS LIST AND CONTACT THE DISIPLINARY DEPARTMENT IF YOU HAVE REGISTERED A NEW PLAYER FOR YOUR CLUB SUSPENSIONS INCURRED BETWEEN 31/01/2019 TO 07/02/2019 DATE INCURRED PLAYER (CLUB) SUSPENSION SPFL - SCOTTISH PREMIERSHIP 30/01/2019 276256 - EUAN DEVENEY (KILMARNOCK F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 01/02/2019 386086 - DEAN RITCHIE (HEART OF MIDLOTHIAN F.C.) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 15/02/2019 03/02/2019 423124 - KRISTOFFER VASSBAKK AJER (CELTIC F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 124842 - SCOTT FRASER MCKENNA (ABERDEEN F.C.) 2 FIRST TEAM MATCHES IMMEDIATE AND 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH FROM 20/02/2019 SPFL – CHAMPIONSHIP 30/01/2019 260210 - DEAN WATSON (PARTICK THISTLE F.C.) (T) 1 CAS U18 MATCH FROM 13/02/2019 02/02/2019 425359 - DAVIS KEILLOR-DUNN (FALKIRK F.C.) 1 SPFL FIRST TEAM LEAGUE MATCH IMMEDIATE 06/02/2019 201729 - BEN -

King George Iv

KING GEORGE IV “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project King George IV HDT WHAT? INDEX KING GEORGE IV KING GEORGE IV 1283 King Edward I of England conquered Wales. DO I HAVE YOUR ATTENTION? GOOD. King George IV “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX KING GEORGE IV KING GEORGE IV 1701 The Act of Settlement declared that those royals who chose to get married with Roman Catholics were to become ineligible for the line of succession to the throne of England. ANTI-CATHOLICISM HDT WHAT? INDEX KING GEORGE IV KING GEORGE IV 1762 August 12, Thursday: George Augustus Frederick was born at St James’s Palace in London, the eldest son of King George III. At birth he automatically became Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay. He would become popularly known as “Prinny” because a few days later the infant would be anointed as Prince of Wales, Earl of Chester, and heir apparent to the British throne. George, the eldest son of George III, was born in 1762. George rebelled against his father’s strict discipline. At the age of eighteen he became involved with an actress, Mrs. Perdita Robinson. This was followed by a relationship with Lady Melbourne. The Prince of Wales also rebelled against his father’s political views. Whereas George III preferred Tory ministers, George, Prince of Wales, was friendly with the Whigs, Charles Fox and Richard Sheridan. In 1784 the Prince of Wales, met a fell in love with Mrs. -

Historical Abuse Systemic Review

Historical Abuse Systemic Review Residential Schools and Children’s Homes in Scotland 1950 to 1995 An independent review led by TOM SHAW orical Abuse Systemic Review e ¡¢ Co ¡ C Foreword 01 Summary 03 Introduction 09 Chapter 1 Context 13 Chapter 2 The Regulatory Framework 35 Chapter 3 The Regulatory Framework: 95 Observations, Conclusions and Recommendations Chapter 4 Compliance, Monitoring and Inspection 105 Chapter 5 Records of Residential Schools 115 and Children’s Homes in Scotland Chapter 6 Former Residents’ Experiences 131 Chapter 7 Conclusions and Recommendations 151 A Final Observation 159 Appendices 163 Appendix I Societal Attitudes to Children 165 and Social Policy Changes 1950 to 1995 Appendix 2 Abuse In Residential Child Care: 177 A Literature Review Appendix 3 Children’s Residential Services: 209 Learning Through Records Appendix 4 A National Records Working Group: 267 Suggested Representation and Terms of Reference Appendix 5 References 271 Appendix 6 Glossary 277 Foreword 1 Foreword As a society we need to learn from the past, to recognise ¨© § C £¤¥ ¦§ e the most valuable and yet the most vulnerable group in society. the good and to understand how to prevent the bad. Learning from our mistakes is a sign of maturity, an indication that we want to do better and, in the context It is our responsibility to respect them, of this review, to do so for all who were or are to care for them, to protect them, to children in the care of the state. acknowledge and respond to their needs and rights. Abuse of children occurs throughout the world; it is a concern in many countries. -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Pie File No

UNITED STATES SECURITI ES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 DIVISION OF TRADING AND MARKETS August 3, 20 15 Ms. Connie Milonakis Davis Polk & Wardwell London LLP 5 Aldermanbury Square London EC2V 7HR England Re: The Royal Bank of Scotland Group pie File No. TP 15-17 Dear Ms. Milonakis: In your letter dated August 3, 2015, as supplemented by conversations with the staff, you request on behalf ofThe Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc, a public limited company organized under the laws of the United Kingdom and registered in Scotland ("RBSG"), an exemption from Rule 102 of Regulation Munder the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended ("Exchange Act") in connection with the distribution of the ordinary shares of RBSG ("RBSG Shares") and the American Depositary Shares each representing the right to receive two RBSG Shares ("RBSG ADSs") by way of a placement of RBSG Shares (the "Placing") to interested purchasers by United Kingdom Financial Investments, which manages the shareholding of the United Kingdom Treasury in RBSG. 1 You seek an exemption to permit RBSG and RBSG Affiliates to conduct specified transactions outside the United States in RBSG Ordinary Shares during the Placing. Specifically, you request that: (i) RBSG CIB be permitted to continue to engage in derivatives and investor product market-making and hedging activities as described in your letter; (ii) the RBSG Asset Manager and RBSG Investment Managers be permitted to continue to engage in investment management activities as described in your letter; (iii) the RBSG Trustees and Personal Representatives be permitted to continue to engage in trustee and personal representative-related activities as described in your letter; (iv) the RBSG Banking Units be permitted to continue to engage in banking-related activities as described in your letter; and (v) the RBSG Stock Borrowing and Lending Units be permitted to continue to engage in stock borrowing and lending activities as described in your letter. -

A Rough Sketch of the History of Stained Glass

MEDIAEVAL STAINED GLASS FROM HOLYROOD ABBEY CHURCH. 81 IV. MEDIAEVAL STAINED GLASS RECENTLY RECOVERED PROE MTH . RUIN F HOLYROOO S D ABBE Y. EELESC CHURCH . P , Y B . P.S.A. SCOT. The fragment f mediaevao s l stained glass e describeaboub o t t d were found on the top of the vaulting of the south aisle of the nave of Holyrood Abbey Church during repairs to the roof in 1909. They have since been ^carefully cleaned and set up to form part of a window e picturth f o e e eas d galleryth en t t a . Their discover f first-claso s yi s importanc o Scottist e h ecclesiastical archaeology, because [hardly yan stained glas s surviveha s d from mediaeval Scotland. ROUGA H SKETCHISTORE TH F STAINEHF O Y O D GLASS. Before describing the Holyrood glass in detail, it will perhaps be n over ru s wel a ,o t lver y briefly e historth , d developmenan y f o t mediaeval stained glass, as a glance at the main points may make t easiei realiso t r exace eth t positio relatiod nan e newl th f no y recovered Holyrood fragments. The ornamentatio f glasno s vessel meany b s f colouso s practisewa r d e Romanbyth s wel a ss othea l r ancient e decorationationsth d an , n oa largf e surfac meany eb numbea f o s f pieceo r f coloureso d glasr o s glazed material carefully fitted together was also well known, but the principlt applieno s windowso dt wa e , althoug e glazinhth f windowgo s with plain glas s knowe Romansth wa s o nt r windofo , w glas founs i s d in almost every Roman fort.