Building with Scottish Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Rough Sketch of the History of Stained Glass

MEDIAEVAL STAINED GLASS FROM HOLYROOD ABBEY CHURCH. 81 IV. MEDIAEVAL STAINED GLASS RECENTLY RECOVERED PROE MTH . RUIN F HOLYROOO S D ABBE Y. EELESC CHURCH . P , Y B . P.S.A. SCOT. The fragment f mediaevao s l stained glass e describeaboub o t t d were found on the top of the vaulting of the south aisle of the nave of Holyrood Abbey Church during repairs to the roof in 1909. They have since been ^carefully cleaned and set up to form part of a window e picturth f o e e eas d galleryth en t t a . Their discover f first-claso s yi s importanc o Scottist e h ecclesiastical archaeology, because [hardly yan stained glas s surviveha s d from mediaeval Scotland. ROUGA H SKETCHISTORE TH F STAINEHF O Y O D GLASS. Before describing the Holyrood glass in detail, it will perhaps be n over ru s wel a ,o t lver y briefly e historth , d developmenan y f o t mediaeval stained glass, as a glance at the main points may make t easiei realiso t r exace eth t positio relatiod nan e newl th f no y recovered Holyrood fragments. The ornamentatio f glasno s vessel meany b s f colouso s practisewa r d e Romanbyth s wel a ss othea l r ancient e decorationationsth d an , n oa largf e surfac meany eb numbea f o s f pieceo r f coloureso d glasr o s glazed material carefully fitted together was also well known, but the principlt applieno s windowso dt wa e , althoug e glazinhth f windowgo s with plain glas s knowe Romansth wa s o nt r windofo , w glas founs i s d in almost every Roman fort. -

Scottish Nationalism

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Summer 2012 Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination Brian Duncan James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Duncan, Brian, "Scottish nationalism: The symbols of Scottish distinctiveness and the 700 Year continuum of the Scots' desire for self determination" (2012). Masters Theses. 192. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/192 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scottish Nationalism: The Symbols of Scottish Distinctiveness and the 700 Year Continuum of the Scots’ Desire for Self Determination Brian Duncan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts History August 2012 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….…….iii Chapter 1, Introduction……………………………………………………………………1 Chapter 2, Theoretical Discussion of Nationalism………………………………………11 Chapter 3, Early Examples of Scottish Nationalism……………………………………..22 Chapter 4, Post-Medieval Examples of Scottish Nationalism…………………………...44 Chapter 5, Scottish Nationalism Masked Under Economic Prosperity and British Nationalism…...………………………………………………….………….…………...68 Chapter 6, Conclusion……………………………………………………………………81 ii Abstract With the modern events concerning nationalism in Scotland, it is worth asking how Scottish nationalism was formed. Many proponents of the leading Modernist theory of nationalism would suggest that nationalism could not have existed before the late eighteenth century, or without the rise of modern phenomena like industrialization and globalization. -

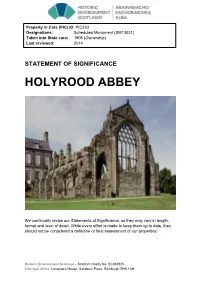

Holyrood Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC223 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM13031) Taken into State care: 1906 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE HOLYROOD ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HOLYROOD ABBEY SYNOPSIS The Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was founded by David I in 1128 as a daughter-house of Merton Priory (Surrey). By the 15th century the abbey was increasingly being used as a royal residence – James II was born there in 1430 - and by the time of the Protestant Reformation (1560) much of the monastic precinct had been subsumed into the embryonic Palace of Holyroodhouse. -

Scotland's Royal Palace

Scotland’s royal palace Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh The Scottish Palace of The Queen The surviving interiors of Scotland’s premier royal palace offer a vivid insight into the 17th-century life of the Court. Simon Thurley unravels the history of an outstanding building Photographs by James Brittain f all The Queen’s palaces, that of Holyroodhouse can claim, with Windsor, to be the most venerable. It has its origins in an Augustin- Oian abbey founded in 1128 and is named after its most precious relic—a fragment of the true cross, a piece of the holy rood. Like their English counterparts, medieval Scot- tish kings often preferred to reside in the comfortable lodgings of a rich abbot rather than the austere towers of their own fortresses. More than Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood became a favoured residence of the Scottish kings, and by the reign of James V, the royal lodgings at the abbey overshadowed the monastic parts (Fig 2). Most impressive of the surviving remains from this early palace are the rooms of Mary Queen of Scots (Country Life, November 23, 1995). Like most royal palaces, Holyroodhouse was horribly abused during the Civil War and Commonwealth, and, at the Restoration, it was very run down. The Scottish Privy Council had a scheme for smartening it up in 1661, but, in 1670, it was decided to almost completely rebuild it. What was constructed between 1671 and 1679 was no normal palace. At the time, it seemed very unlikely that Charles II would ever visit Edinburgh, let The Royal Collection alone live there. The royal apartments were ➢ Fig 1: The King’s Bedchamber with its 1680s state bed. -

The Coronation Stone Was Read by the Author, As Senior Vice-President of the Society of Anti- Quaries of Scotland, at a Meeting of the Society Held on the 8Th Of

I ^ II t llll' 'X THE COEONATION STONE Privted by R. Clark, EDMONSTON S: DOUGLAS, EDINRURGH. LONDON HAMILTON, AnA^L';, AMD CO. Clje Coronation g>tone WILLIAM F. SKENE ':<©^=-f#?2l^ EDINBURGH : EDMONSTON & DOUGLAS MDCCCLXIX. — . PREFATORY NOTE. This analysis of the legends connected with the Coronation Stone was read by the author, as Senior Vice-President of the Society of Anti- quaries of Scotland, at a Meeting of the Society held on the 8th of March last. A limited impression is now published with Notes and Illus- trations. The latter consist of I. The Coronation Chair, with the stone under the seat, as it is at present seen in Westminster Abbey, im the rover. II. The reverse of the Seal of the Abbey of Scone, showing the Scottish King seated in the Eoyal Chair, on the title-page. III. Ancient Scone, as i-epresented in the year 1693 in Slezer's Theatntm Scofim, to precede page 1 a. Chantorgait. h. Friar's Den. c. Site of Abbey. d. Palace. e. Moot Hill, with the Church built in 1624 upon it. /'. The river Tay. IV. The Coronation Chair as shewn by HoUinshed in 1577, ptoge 12. V. Coronation of Alexander III., from the MS. of Fordun, con- tained in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. This is a MS. of the Scoticronicon, as altered, interpolated, and continued by Bower, ojyposite Latin description in the Appendix, page 47. 20 Inverleith Kow, Edinbukgh, 7/// Jan,' 1869. The Prospect of the Horn a. Chantorcjait. i. SlTK OF AliKEV. /'. Fkiak's Dkn. ./. Pai.ack. -

'In Me Porto Crucem': a New Light on the Lost St Margaret's Crux Nigra

© The Author(s) 2020. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. ‘In me porto crucem’: a new light on the lost St Margaret’s crux nigra Francesco Marzella Abstract St Margaret of Scotland owned a reliquary containing a relic of the True Cross known as crux nigra. Both Turgot, Margaret’s biographer, and Aelred of Rievaulx, who spent some years at the court of Margaret’s son, King David, mention the reliquary without offering sufficient information on its origin. The Black Rood was probably lost or destroyed in the sixteenth century. Some lines written on the margins of a twelfth- century manuscript containing Aelred’s Genealogia regum Anglorum can now shed a new light on this sacred object. The mysterious lines, originally written on the Black Rood or more probably on the casket in which it was contained, claim that the relic once belonged to an Anglo-Saxon king, and at the same time they seem to convey a signifi- cant political message. In his biography of St Margaret of Scotland,1 Turgot († 1115),2 at the time prior of Durham, mentioned an object that was particularly dear to the queen. It was a cross known as crux nigra. In chapter XIII of his Vita sanctae Margaretae, Turgot tells how the queen wanted to see it for the last time when she felt death was imminent: 3 Ipsa quoque illam, quam Nigram Crucem nominare, quamque in maxima semper ven- eratione habere consuevit, sibi afferri præcepit. -

The Shroud of Turin and Related Objects – an Overview

The Shroud of Turin and Related Objects – An Overview It is amazing but true that there are many Personal Effects of Jesus of Nazareth that may still exist in the world, attesting to the existence of Jesus in history. This exhibit presents these Personal Effects, as seen by modern scientists and researchers for the benefit of the general public, inspired by the magnificent plates below from Memoire Sur Les Instruments de la Passion, by Charles Rohault DeFleury, published in 1870, and building upon his research. Personal Effects of the House of David St. Anne – the Mother of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Mother of Jesus The significance of St. Anne is that conceived the mother of Jesus immaculately. This was confirmed by the private apparitions at Rue de Bac, with the Miraculous Medal, and especially at Lourdes, France, in 1858, four years after Pope Pius IX had formerly declared the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception. The Relics of St. Anne in Apt The Relics of St. Anne at St. Anne De Auray The Relics of St. Anne in Beaupre, Canada The Relics of St. Anne in Cairo, New York Relic of St. Anne in Sturbridge, Massachusetts Relic of St. Anne at Jean Baptiste, Manhattan Relic of St. Anne at St. Adalbart Church, Staten Island, New York Relic of St. Anne in Waterbury, Connecticut Relic of St. Anne in Chicopee, Massachusetts Relic of St. Anne Church in Jerusalem at Fall River, Massachusetts Relics of St. Joachim Relics of Elizabeth, Zechariah and John the Baptist Relics of St. Joseph To our awareness, no one knows where Joseph, the putative father of Jesus is actually buried, and much about him, is legendary in nature. -

The Coronation Stone. by William F. Skenb, Esq., Ll.D

I I. E CORONATIOTH N STONE WILLIAY B . M. SKENBF , ESQ., LL.D., VlCE-PKKSIDEN . SCOTA . TS . The Legene Coronatioth f o d n Ston f Scotlandeo , formerl t Sconeya , Westminsten i anw dno r Abhey intimatels i , y connected wit fabuloue hth s histor Scotlandf y o wandering s it tale f eo Th . s from Egyp Sconeo t d an , of its various resting-places by the way, is, in fact, closely interwoven with that spurious history which, first emerging in the controversy with England regarding the independence of Scotland, was wrought into a consistent narrative by Fordun, and finally elaborated by Hector Boece into that formidable lisf mythio t c monarchs swayeo wh ,e sceptrdth e over the Scottish race from " the Marble Chair" in Dunstaffnage. The mists cast aroun e trudth e histor f Scotlanyo thiy b ds fictitious narrative havbeen greaw a en no i , t measure, dispelled. Modern criticism s demolisheha e fortth d y kings whose portraits adore e wallth nth f o s gallery in Holyrood, and whose speeches are given at such wearisome lengte page e legenStonth e th th f Boecen h i s f o Destinyt f eo do Bu . , or Fatal Chair, has taken such hold of the Scottish mind, that it is less easily dislodged from its place in the received history of the country; and there it still stands, in all its naked improbability, a solitary waif from f myt o d fable a an h se , e witth h which modern criticis s hardlmha y venture o meddlet d d whican , h modern scepticis t caveno o ds t mha question s stili t lI believe. -

Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads

THE CAUSE Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads Mary Ellen Brown• • , Editor Contents Acknowledgements The Cause The Letters Index Acknowledgments The letters between Francis James Child and William Macmath reproduced here belong to the permanent collections of the Houghton Library, Harvard University and the Hornel Library, Broughton House, Kirkcudbright, a National Trust for Scotland property. I gratefully acknowledge the help and hospitality given me by the staffs of both institutions and their willingness to allow me to make these materials more widely available. My visits to both facilities in search of data, transcribing hundreds of letters to bring home and analyze, was initially provided by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial and Andrew W. Mellon foundations and subsequently—for checking my transcriptions and gathering additional material--by the Office of the Provost for Research at Indiana University Bloomington. This serial support has made my work possible. Quite unexpectedly, two colleagues/friends met me the last time I was in Kirkcudbright (2014) and spent time helping me correct several difficult letters and sharing their own perspectives on these and other materials—John MacQueen and the late Ronnie Clark. Robert E. Lewis helped me transcribe more accurately Child’s reference and quotation from Chaucer; that help reminded me that many of the letters would benefit from copious explanatory notes in the future. Much earlier I benefitted from conversations with Sigrid Rieuwerts and throughout the research process with Emily Lyle. Both of their published and anticipated research touches on related publications as they have sought to explore and make known the rich past of Scots and the study of ballads. -

![By GEOKGE SETON, Esq., F.S.A.Sc. [Bead to the Society, 13Th January 1851.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1907/by-geokge-seton-esq-f-s-a-sc-bead-to-the-society-13th-january-1851-6591907.webp)

By GEOKGE SETON, Esq., F.S.A.Sc. [Bead to the Society, 13Th January 1851.]

440 XXXIX. Notice of the ancient Incised Slabs in the Abbey Church of Holyrood, (illustrated by a Series of Rubbings). By GEOKGE SETON, Esq., F.S.A.Sc. [Bead to the Society, 13th January 1851.] " And marble monuments were here displayed Thronging the walls; and on the floor beneath, Sepulchral stones appeared with emblems graven, And foot-worn epitaphs, and some with small And shining effigies of brass inlaid." WORDSWORTH'S " Excursion." Having in a former paper, on the subject of " Monumental Brasses," made a few introductory remarks on the interest and importance of the re- cords of the tomb, more especially in connection with man's sense of immorta- lity, I shall at once proceed to notice that curious class of sepulchral remains bearing the name of Incised Slabs, of which numerous examples occur in va- rious parts of the kingdom. According to Mr Cutt,1 these monuments were in common use among the Romans and Romanized nations at the com- mencement of the Christian era, and besides being inscribed with the name of the deceased person whom they commemorated, they frequently displayed the symbol of his calling and other emblematical devices. A similar fashion was adopted by the early Christians, many of whose monuments (still pre- served in the Lapidarian Gallery of the Vatican at Rome) exhibit, in addi- tion to the usual inscriptions, the figure of a Cross, Fish, or some other appropriate symbol. In the course of a few centuries, Incised Cross Slabs became very common throughout the whole of Christendom, and we can now obtain a connected series of these Christian gravestones from the times of the Apostles to the present day. -

Download the Life of Sir Richard Burton

The Life of Sir Richard Burton by Thomas Wright The Life of Sir Richard Burton by Thomas Wright This etext was scanned by JC Byers; proofread by Laura Shaffer. THE LIFE OF SIR RICHARD BURTON By THOMAS WRIGHT Author of "The Life of Edward Fitzgerald," etc. 2 Volumes in 1 This Work is Dedicated to Sir Richard Burton's Kinsman And Friend, Major St. George Richard Burton, The Black Watch. page 1 / 640 Preface. Fifteen years have elapsed since the death of Sir Richard Burton and twelve since the appearance of the biography of Lady Burton. A deeply pathetic interest attaches itself to that book. Lady Burton was stricken down with an incurable disease. Death with its icy breath hung over her as her pen flew along the paper, and the questions constantly on her lips were "Shall I live to complete my task? Shall I live to tell the world how great and noble a man my husband was, and to refute the calumnies that his enemies have so industriously circulated?" She did complete it in a sense, for the work duly appeared; but no one recognised more clearly than herself its numerous shortcomings. Indeed, it is little better than a huge scrap-book filled with newspaper cuttings and citations from Sir Richard's and other books, hurriedly selected and even more hurriedly pieced together. It gives the impressions of Lady Burton alone, for those of Sir Richard's friends are ignored--so we see Burton from only one point of view. Amazing to say, it does not contain a single original anecdote[FN#1]--though perhaps, more amusing anecdotes could be told of Burton than of any other modern Englishman. -

Pilgrimage to Scotland & Ireland Tour

Pilgrimage to Scotland & Ireland Tour 217 13 Days www.206tours.com/tour217 Edinburgh · St. Andrews · Perth · Glasgow · Carfin Motherwell · Dublin · Wicklow · Glendalough Tipperary · Rock Of Cashel · Kerry · Dingle Peninsula · Shannon · Cliffs Of Moher · Corcomroe Abbey Galway Corrib Lake · Clonmacnoise · Knock YOUR TRIP INCLUDES • Luggage handling (1 piece per person) • Round-trip airfare from your desired Airport • Flight bag & portfolio of all travel documents • Book without airfare (land only option) • All airport taxes & fuel surcharges NOT INCLUDED: Lunches, Tips to your guide & driver • Centrally located hotels: (or similar) • 1 night: Hotel Edinburgh Grosvenor, Edinburgh OPTIONAL • 2 nights: Hilton Garden Inn, Glasgow Travel Insurance • 1 night: Trinity Capital, Dublin Providing you coverage for both pre-existing • 1 night: Minella, Tipperary conditions and those that may arise during your trip, including medical and dental emergencies, loss of • 2 nights: Castlerosse, Killarney luggage, trip delay, and so much more. • 2 nights: Salthill, Galway • 1 night: Knock House, Knock SUPPLEMENTAL CANCELLATION PROTECTION • 1 night: Trinity Capital, Dublin A Cancellation Waiver - allowing you to cancel your • Transfers as per itinerary trip and receive a refund anytime - up until 24 hours • Breakfast and Dinner daily prior to departure. The “Waiver” expires once you are within 24 hours of departure. • Wine with dinners • Transportation by air-conditioned motor coach • Assistance of a professional local guide Throughout • Sightseeing and admissions fees as per itinerary • Catholic Priest available for Spiritual Direction • Mass daily & Spiritual activities ABOUT YOUR TRIP holds much historical significance as its purpose has The practice of Pilgrimage is almost as old as transformed from a battle ground, to a home, to an recorded history.