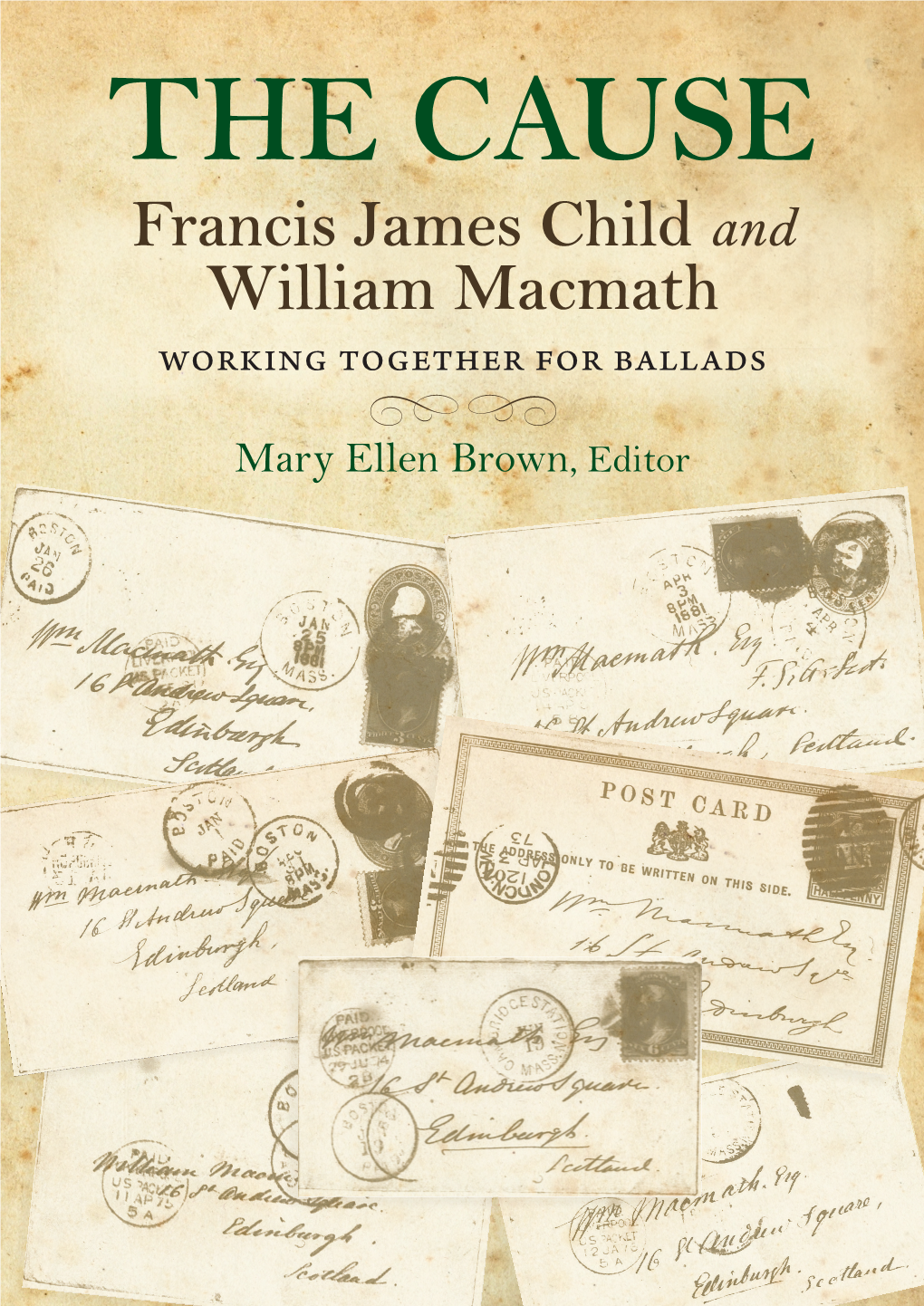

Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Issues in Ballads and Songs, Edited by Matilda Burden

SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Edited by MATILDA BURDEN Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications SOCIAL ISSUES IN BALLADS AND SONGS Social Issues in Ballads and Songs Edited by MATILDA BURDEN STELLENBOSCH KOMMISSION FÜR VOLKSDICHTUNG 2020 Kommission für Volksdichtung Special Publications Copyright © Matilda Burden and contributors, 2020 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. Peer-review statement All papers have been subject to double-blind review by two referees. Editorial Board for this volume Ingrid Åkesson (Sweden) David Atkinson (England) Cozette Griffin-Kremer (France) Éva Guillorel (France) Sabina Ispas (Romania) Christine James (Wales) Thomas A. McKean (Scotland) Gerald Porter (Finland) Andy Rouse (Hungary) Evelyn Birge Vitz (USA) Online citations accessed and verified 25 September 2020. Contents xxx Introduction 1 Matilda Burden Beaten or Burned at the Stake: Structural, Gendered, and 4 Honour-Related Violence in Ballads Ingrid Åkesson The Social Dilemmas of ‘Daantjie Okso’: Texture, Text, and 21 Context Matilda Burden ‘Tlačanova voliča’ (‘The Peasant’s Oxen’): A Social and 34 Speciesist Ballad Marjetka Golež Kaučič From Textual to Cultural Meaning: ‘Tjanne’/‘Barbel’ in 51 Contextual Perspective Isabelle Peere Sin, Slaughter, and Sexuality: Clamour against Women Child- 87 Murderers by Irish Singers of ‘The Cruel Mother’ Gerald Porter Separation and Loss: An Attachment Theory Approach to 100 Emotions in Three Traditional French Chansons Evelyn Birge Vitz ‘Nobody loves me but my mother, and she could be jivin’ too’: 116 The Blues-Like Sentiment of Hip Hop Ballads Salim Washington Introduction Matilda Burden As the 43rd International Ballad Conference of the Kommission für Volksdichtung was the very first one ever to be held in the Southern Hemisphere, an opportunity arose to play with the letter ‘S’ in the conference theme. -

The Sinclair Macphersons

Clan Macpherson, 1215 - 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson, 20 January 2011 Not for sale, free download available from www.reynoldmacpherson.ac.nz Clan Macpherson, 1215 to 1550 How the Macphersons acquired their traditional Clan Lands and Independence Reynold Macpherson Introduction The Clan Macpherson Museum (see right) is in the village of Newtonmore, near Kingussie, capital of the old Highland district of Badenoch in Scotland. It presents the history of the Clan and houses many precious artifacts. The rebuilt Cluny Castle is nearby (see below), once the home of the chief. The front cover of this chapter is the view up the Spey Valley from the memorial near Newtonmore to the Macpherson‟s greatest chief; Col. Ewan Macpherson of Cluny of the ‟45. Clearly, the district of Badenoch has long been the home of the Macphersons. It was not always so. This chapter will make clear how Clan Macpherson acquired their traditional lands in Badenoch. It means explaining why Clan Macpherson emerged from the Old Clan Chattan, was both a founding member of the Chattan Confederation and yet regularly disputed Clan Macintosh‟s leadership, why the Chattan Confederation expanded and gradually disintegrated and how Clan Macpherson gained its property and governance rights. The next chapter will explain why the two groups played different roles leading up to the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The following chapter will identify the earliest confirmed ancestor in our family who moved to Portsoy on the Banff coast soon after the battle and, over the decades, either prospered or left in search of new opportunities. -

The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe

B AR B ARA C HING Happily Ever After in the Marketplace: The Ballads of the Southern Mountains and the Escape from Old Europe Between 1882 and 1898, Harvard English Professor Francis J. Child published The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, a five volume col- lection of ballad lyrics that he believed to pre-date the printing press. While ballad collections had been published before, the scope and pur- ported antiquity of Child’s project captured the public imagination; within a decade, folklorists and amateur folk song collectors excitedly reported finding versions of the ballads in the Appalachians. Many enthused about the ‘purity’ of their discoveries – due to the supposed isolation of the British immigrants from the corrupting influences of modernization. When Englishman Cecil Sharp visited the mountains in search of English ballads, he described the people he encountered as “just English peasant folk [who] do not seem to me to have taken on any distinctive American traits” (cited in Whisnant 116). Even during the mid-century folk revival, Kentuckian Jean Thomas, founder of the American Folk Song Festival, wrote in the liner notes to a 1960 Folk- ways album featuring highlights from the festival that at the close of the Elizabethan era, English, Scotch, and Scotch Irish wearied of the tyranny of their kings and spurred by undaunted courage and love of inde- pendence they braved the perils of uncharted seas to seek freedom in a new world. Some tarried in the colonies but the braver, bolder, more venturesome of spirit pressed deep into the Appalachians bringing with them – hope in their hearts, song on their lips – the song their Anglo-Saxon forbears had gathered from the wander- ing minstrels of Shakespeare’s time. -

Make We Merry More and Less

G MAKE WE MERRY MORE AND LESS RAY MAKE WE MERRY MORE AND LESS An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature An Anthology of Medieval English Popular Literature SELECTED AND INTRODUCED BY DOUGLAS GRAY EDITED BY JANE BLISS Conceived as a companion volume to the well-received Simple Forms: Essays on Medieval M English Popular Literature (2015), Make We Merry More and Less is a comprehensive anthology of popular medieval literature from the twel�h century onwards. Uniquely, the AKE book is divided by genre, allowing readers to make connec�ons between texts usually presented individually. W This anthology offers a frui�ul explora�on of the boundary between literary and popular culture, and showcases an impressive breadth of literature, including songs, drama, and E ballads. Familiar texts such as the visions of Margery Kempe and the Paston family le�ers M are featured alongside lesser-known works, o�en oral. This striking diversity extends to the language: the anthology includes Sco�sh literature and original transla�ons of La�n ERRY and French texts. The illumina�ng introduc�on offers essen�al informa�on that will enhance the reader’s enjoyment of the chosen texts. Each of the chapters is accompanied by a clear summary M explaining the par�cular delights of the literature selected and the ra�onale behind the choices made. An invaluable resource to gain an in-depth understanding of the culture ORE AND of the period, this is essen�al reading for any student or scholar of medieval English literature, and for anyone interested in folklore or popular material of the �me. -

01 Prelude | | |--02 City of Refuge | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen

|--Abigail Washburn | |--City of Refuge | | |--01 Prelude | | |--02 City of Refuge | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen | | |--04 Chains | | |--05 Ballad of Treason | | |--06 Last Train | | |--07 Burn Thru | | |--08 Corner Girl | | |--09 Dreams Of Nectar | | |--10 Divine Bell | | |--11 Bright Morning Stars | | |--cover | | `--folder | |--Daytrotter Studio | | |--01 City of Refuge | | |--02 Taiyang Chulai | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen | | |--04 Chains | | |--06 What Are They Doing | | `--07 Keys to the Kingdom | |--Live at Ancramdale | | |--01 Main Stageam Set | | |--02 Intro | | |--03 Fall On My Knees | | |--04 Coffee’s Cold | | |--05 Eve Stole The Apple | | |--06 Red & Blazey | | |--07 Journey Home | | |--08 Key To The Kingdom | | |--09 Sometime | | |--10 Abigail talks about the trip to Tibet | | |--11 Song Of The Traveling Daughter | | |--12 Crowd _ Band Intros | | |--13 The Sparrow Watches Over Me | | |--14 Outro | | |--15 Master's Workshop Stage pm Set | | |--16 Tuning, Intro | | |--17 Track 17 of 24 | | |--18 Story about Learning Chinese | | |--19 The Lost Lamb | | |--20 Story About Chinese Reality TV Show | | |--21 Deep In The Night | | |--22 Q & A | | |--23 We’re Happy Working Under The Sun | | |--24 Story About Trip To China | | |--index | | `--washburn2006-07-15 | |--Live at Ballard | | |--01 Introduction | | |--02 Red And Blazing | | |--03 Eve Stole The Apple | | |--04 Free Internet | | |--05 Backstep Cindy_Purple Bamboo | | |--06 Intro. To The Lost Lamb | | |--07 The Lost Lamb | | |--08 Fall On My Knees | | |--Aw2005-10-09 | | `--Index -

Purgatoire Saint Patrice, Short Metrical Chronicle, Fouke Le Fitz Waryn, and King Horn

ROMANCES COPIED BY THE LUDLOW SCRIBE: PURGATOIRE SAINT PATRICE, SHORT METRICAL CHRONICLE, FOUKE LE FITZ WARYN, AND KING HORN A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Catherine A. Rock May 2008 Dissertation written by Catherine A. Rock B. A., University of Akron, 1981 B. A., University of Akron, 1982 B. M., University of Akron, 1982 M. I. B. S., University of South Carolina, 1988 M. A. Kent State University, 1991 M. A. Kent State University, 1998 Ph. D., Kent State University, 2008 Approved by ___________________________________, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Susanna Fein ___________________________________, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Don-John Dugas ___________________________________ Kristen Figg ___________________________________ David Raybin ___________________________________ Isolde Thyret Accepted by ___________________________________, Chair, Department of English Ronald J. Corthell ___________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Jerry Feezel ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………viii Chapter I. Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Significance of the Topic…………………………………………………..2 Survey of the State of the Field……………………………………………5 Manuscript Studies: 13th-14th C. England………………………...5 Scribal Studies: 13th-14th C. England……………………………13 The Ludlow Scribe of Harley 2253……………………………...19 British Library -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Robin Hood the Brute: Representations of The

Law, Crime and History (2016) 2 ROBIN HOOD THE BRUTE: REPRESENTATIONS OF THE OUTLAW IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY CRIMINAL BIOGRAPHY Stephen Basdeo1 Abstract Eighteenth century criminal biography is a topic that has been explored at length by both crime historians such as Andrea McKenzie and Richard Ward, as well as literary scholars such as Lincoln B. Faller and Hal Gladfelder. Much of these researchers’ work, however, has focused upon the representation of seventeenth and eighteenth century criminals within these narratives. In contrast, this article explores how England’s most famous medieval criminal, Robin Hood, is represented. By giving a commentary upon eighteenth century Robin Hood narratives, this article shows how, at a time of public anxiety surrounding crime, people were less willing to believe in the myth of a good outlaw. Keywords: eighteenth century, criminal biography, Robin Hood, outlaws, Alexander Smith, Charles Johnson, medievalism Introduction Until the 1980s Robin Hood scholarship tended to focus upon the five extant medieval texts such as Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood and the Potter, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne, and A Gest of Robyn Hode (c.1450), as well as attempts to identify a historical outlaw.2 It was only with the work of Stephen Knight that scholarship moved away from trying to identify a real outlaw as things took a ‘literary turn’. With Knight’s work also the post- medieval Robin Hood tradition became a significant area of scholarly enquiry. His recent texts have mapped the various influences at work upon successive interpretations of the legend and how it slowly became gentrified and ‘safe’ as successive authors gradually ‘robbed’ Robin of any subversive traits.3 Whilst Knight’s research on Robin Hood is comprehensive, one genre of literature that he has not as yet examined in detail is eighteenth century criminal biography. -

The Chartist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’S Royston Gower; Or, the Days of King John (1838)

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 44 Article 8 Issue 2 Reworking Walter Scott 12-31-2019 The hC artist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The aD ys of King John (1838) Stephen Basdeo Richmond: the American International University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Basdeo, Stephen (2019) "The hC artist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The aD ys of King John (1838)," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 44: Iss. 2, 72–81. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol44/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHARTIST ROBIN HOOD: THOMAS MILLER’S ROYSTON GOWER; OR, THE DAYS OF KING JOHN (1838) Stephen Basdeo Thomas Miller was born in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire in 1807, to a poor family and in his early youth worked as a ploughboy before becoming a shoemaker’s apprentice. He had a limited education, but his mother encouraged him to read on a daily basis.1 In his adult life, he became a professional author. He greatly admired Walter Scott, whom he referred to as “the immortal author of Waverley.”2 Indeed, such was his admiration that it was in emulation of Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819) that Miller authored his own Robin Hood novel titled Royston Gower; or, The Days of King John, published in December 1838.3 Ivanhoe had a profound influence upon the Robin Hood legend. -

Stories from Scottish History Madaleng

j|i K^ miw^gi n QassT)A7U Book ^^ CATHERINE THRUST HER OWN ARM ACROSS THE DOOR i^-Mr STORIES FROM SCOTTISH HISTORY MADALENG. EDGAR. m %m > NEW YORK T. Y. CROWELL fi CO. PUBLISHERS Copyright, 1906, By THOMAS Y. CROWELL & COMPANY v-s Cf CONTENTS CHAP. IV Contents CHAP. PAGE XIX. James II and the Black Douglasses- (i) At Edinburgh Castle (2) At Thrieve Castle (3) At Stirling Castle (4) At Roxburgh Castle XX. A King's Fears . XXI. Cochran and Bell-the-Cat XXII. The Fatal Shrift XXIII. Stout Hearts XXIV. A Gallant King . XXV. The Strong Ship Lion . XXVI. Flodden Field XXVII. A Dash for Liberty XXVIII. John Armstrong , XXIX. The Goodman of Ballengiech XXX. WisHART and Beaton . XXXI. Queen Mary's Youth . XXXII. Kirk o' Field XXXIII. The Earl of Bothwell XXXIV. The Queen's Flight . XXXV. Troublous Times XXXVI. Queen Mary in Prison XXXVII. Fotheringay Castle XXXVIII. James VI and Kinmont Willie XXXIX. The Gowrie-House Mystery XL. The Union .... Chronological Table . Preface present a selection from Sir Walter ToScott's " Tales of a Grandfather " ap- pears at first sight to be taking an unpardonable Hberty with such an established favorite. The size of the storehouse, however, is apt to discourage search for the treasures within, and it is possible that many of the " Tales " may be en- joyed by children who yet could not make their way through the whole book. In the present volume, the stories are taken from the First Series, and, since space forbids a wider range, all lie between the rise of William Wallace and the Union of the crowns. -

Mikee Delony Abilene Christian University Peer-Reviewed Robin

A REVIEW OF THE YEAR’S PUBLICATIONS IN ROBIN HOOD SCHOLARSHIP Mikee Delony Abilene Christian University Peer-reviewed Robin Hood scholarship published in 2015 includes two single-author books, two edited book chapters, and eight journal articles. These publications examine specific texts from the matter of Robin Hood, providing new approaches to familiar texts and further exploration of less-familiar materials. Many scholars also comment on the tradition’s capacity for seemingly endless adaptation and highlight the similar ideological and political threads woven through the materials. Shining an academic light upon five centuries of Robin Hood texts that celebrate political resistance and public activism against oppression takes on new importance in light of contemporary global resistance to government overreach and systemic oppression. Since Robin Hood scholarship also tends to resist categorization, I have loosely grouped these reviews by literary chronology and genre. GENERAL STUDIES In Reading Robin Hood: Content, Form, and Reception in the Outlaw Myth,1 Stephen Knight revisits the Robin Hood literary tradition from his position as one of the early pioneers in the field of Robin Hood studies. In his survey, which ranges from medieval oral ballads to twenty- first film and television adaptations, Knight notes the multivalent, “unhierarchial, nonlinear” (10) nature of the tradition and suggests that Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic “model of multiplicity” (234) might best describe the “various, porous, [and] richly labile” legend (10). Writing that the Robin Hood tradition “renews itself in turns of current political forces and media of dissemination and consistently has as scant a respect for literary and formalistic authority as it has for social and legal forces of order” (253), Knight celebrates the characteristics that prevent the tradition from achieving canonical status at the same time they have remained relevant for centuries. -

The Flowering Thorn: International Ballad Studies

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 1-1-2003 The loF wering Thorn Thomas A. McKean Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation McKean, T. A. (2003). The flowering thorn: International ballad studies. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Flowering Thorn International Ballad Studies INTRO Flowering Thorn.p65 1 9/25/03, 02:16 INTRO Flowering Thorn.p65 2 9/25/03, 02:16 The Flowering Thorn International Ballad Studies edited by Thomas A. McKean A project of the Kommission für Volksdichtung and the Elphinstone Institute Utah State University Press Logan, Utah INTRO Flowering Thorn.p65 3 9/25/03, 02:16 Copyright © 2003 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan Utah 84322–7800 Cover and book design and typesetting by Thomas A. McKean. Cover photograph: Hawthorn (Cratægus monogyna ), Schivas, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, June 2003, Thomas A. McKean. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The flowering thorn : international ballad studies / edited by Thomas A. McKean. p. cm. “A project of the Kommission für Volksdichtung and the Elphinstone Institute.” Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-87421-568-4 (alk. paper) 1. Ballads—History and criticism. 2. Folk literature—History and criticism. I.