Stories from Scottish History Madaleng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

MA Dissertatio

Durham E-Theses Northumberland at War BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST How to cite: BROAD, WILLIAM,ERNEST (2016) Northumberland at War, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11494/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT W.E.L. Broad: ‘Northumberland at War’. At the Battle of Towton in 1461 the Lancastrian forces of Henry VI were defeated by the Yorkist forces of Edward IV. However Henry VI, with his wife, son and a few knights, fled north and found sanctuary in Scotland, where, in exchange for the town of Berwick, the Scots granted them finance, housing and troops. Henry was therefore able to maintain a presence in Northumberland and his supporters were able to claim that he was in fact as well as in theory sovereign resident in Northumberland. -

Parish Clerks Report.Pdf

Parish Clerk’s Report 6-28 February, 2008 Item 3a Damage to seat at Mill Corner: At the time of writing I have nothing further to report on this matter. I hope I will be able to speak to the haulage contractor before the meeting. Item 3c Munro’s buses: Since the last meeting I have spoken to the Parish Clerks to Belsay, Capheaton, Kirkwhelpington and Rochester in an attempt to gather documentary evidence to submit to Northumberland County Council. They all support Otterburn’s effort to have a bigger bus used on the Jedburgh-Newcastle route. We have agreed that I will produce posters seeking information from the public and will co-ordinate the responses. Items 3e Grants to local organisations: Since the last meeting I have received acknowledgements from First Responders, Tynedale CAB (which has dealt with 6 Otterburn residents in the last year) and the Friends of Bellingham Surgery. All are grateful for the donations received. I await an acknowledgement from Woodchips. Item 3f Tynedale Visitor: The following was prepared at the request of the Hexham Courant: ‘THE village of Otterburn is at the heart of Redesdale, a remote upland valley steeped in history and blessed with natural beauty. The Percy Cross stands in the midst of a small plantation, a mile north of the village. Near this peaceful spot, on an August evening in 1388, an English army of 8,000 men followed Sir Henry Percy into battle against the Scots, led by the Earl of Douglas. The battle of Otterburn ended in an English rout. -

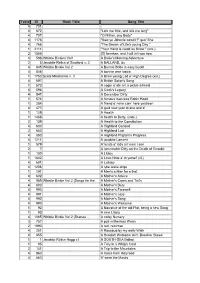

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4

Table ID Book Titile Song Title 4 701 - 4 672 "Lo'e me little, and lo'e me lang" 4 707 "O Mither, ony Body" 4 1176 "Saw ye Johnnie comin'?" quo' She 4 766 "The Dream of Life's young Day " 1 2111 "Your Hand is cauld as Snaw " (xxx.) 2 1555 [O] hearken, and I will tell you how 4 596 Whistle Binkies Vol1 A Bailie's Morning Adventure 2 5 Jacobite Relics of Scotland v. 2 A BALLAND, &c 4 845 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 A Bonnie Bride is easy buskit 4 846 A bonnie wee lassie 1 1753 Scots Minstrelsie v. 3 A Braw young Lad o' High Degree (xxi.) 4 597 A British Sailor's Song 1 573 A cogie o' ale an' a pickle aitmeal 4 598 A Cook's Legacy 4 847 A December Dirty 1 574 A famous man was Robin Hood 1 284 A friend o' mine cam' here yestreen 4 477 A guid new year to ane and a' 1 129 A Health 1 1468 A health to Betty, (note,) 2 139 A Health to the Constitution 4 600 A Highland Garland 2 653 A Highland Lad 4 850 A Highland Pilgram's Progress 4 1211 A jacobite Lament 1 579 A' kinds o' lads an' men I see 2 7 A lamentable Ditty on the Death of Geordie 1 130 A Litany 1 1842 A Love-Note a' to yersel' (xi.) 4 601 A Lullaby 4 1206 A lyke wake dirge 1 291 A Man's a Man for a that 4 602 A Mother's Advice 4 989 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Songs for the A Mother's Cares and Toil's 4 603 Nursery) A Mother's Duty 4 990 A Mother's Farewell 4 991 A Mother's Joys 4 992 A Mother's Song 4 993 A Mother's Welcome 1 92 A Narrative of the old Plot; being a new Song 1 93 A new Litany 4 1065 Whistle Binkie Vol 2 (Scenes … A noisy Nursery 3 757 Nursery) A puir mitherless Wean 2 1990 A red, red rose 4 251 A Rosebud by my early Walk 4 855 A Scottish Welcome to H. -

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for January 4Th, 2019

Electric Scotland's Weekly Newsletter for January 4th, 2019 To see what we've added to the Electric Scotland site view our What's New page at: http://www.electricscotland.com/whatsnew.htm To see what we've added to the Electric Canadian site view our What's New page at: http://www.electriccanadian.com/whatsnew.htm For the latest news from Scotland see our ScotNews feed at: https://electricscotland.com/scotnews.htm Electric Scotland News Wishing everyone a Very Happy New Year. At this time the overwhelming thought is about Brexit as what is decided will tell us how Britain will fair in the months and years ahead. I personally hope that we'll go for a "no deal" and thus save the £39 billion for ourselves and be free to trade with the world. BUT we shall see what happens over the next three months and get some idea of what is coming when the Parliament vote in January. ------- Here is the video introduction to this newsletter... https://youtu.be/PDypjeUrl3o Scottish News from this weeks newspapers Note that this is a selection and more can be read in our ScotNews feed on our index page where we list news from the past 1-2 weeks. I am partly doing this to build an archive of modern news from and about Scotland as all the newsletters are archived and also indexed on Google and other search engines. I might also add that in newspapers such as the Guardian, Scotsman, Courier, etc. you will find many comments which can be just as interesting as the news story itself and of course you can also add your own comments if you wish. -

Cdsna Septs 2011-07

Septs of Clan Douglas Officially Recognized by Clan Douglas Society of North America July 2011 Harold Edington Officially Recognized Septs of Clan Douglas As listed in the CDSNA 2009 Bylaws Septs of Clan Douglas © 2011 Harold A Edington All Rights Reserved. i Septs of Clan Douglas Table of Contents CDSNA Recognized Septs of Clan Douglas * Indicates a separate clan recognized by The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs . Page Page iii Introduction 48 Glenn v Sept Criteria 49 Harkness 8 Agnew* 50 Inglis 11 Blackett 519 Kilgore 11 Blacklock 53 Kirkland 11 Blaylock 54 Kilpatrick 11 Blackstock 54 Kirkpatrick 14 Blackwood 62 Lockerby 18 Breckinridge 63 Lockery 23 Brown (Broun) * 64 MacGuffey 24 Brownlee 64 MacGuffock 27 Cavan 65 M(a)cKittrick 29 Cavers 66 Morton 34 Dickey (Dickie, Dick) 70 Sandilands* 37 Drysdale 70 Sandlin 38 Forest/Forrest 73 Soule/Soulis 38 Forrester/Forster 75 Sterrett 38 Foster 78 Symington (Simms, Syme) 41 Gilpatric 83 Troup 42 Glendenning 84 Young (Younger) Appendix: Non-Sept Affiliated Surnames These are surnames that have a strong connection to Douglas but are not (yet) considered septs of Douglas by CDSNA Begins after page 86. i Septs of Clan Douglas i Septs of Clan Douglas Introduction Whether you are an older or a newer member of Clan Douglas, you have probably done a websearch of Clan Douglas. Any such search will likely present you with a number of sites listing “recognized” or “official” septs of Clan Douglas. And if you were to compile a list of all the listed surnames claimed to be Douglas septs, in addition -

Northumberland Yesterday and To-Day

Northumberland Yesterday and To-day Jean F. Terry Project Gutenberg's Northumberland Yesterday and To-day, by Jean F. Terry This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Northumberland Yesterday and To-day Author: Jean F. Terry Release Date: February 17, 2004 [EBook #11124] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NORTHUMBERLAND *** Produced by Miranda van de Heijning, Margaret Macaskill and PG Distributed Proofreaders [Illustration: BAMBURGH CASTLE.] Northumberland Yesterday and To-day. BY JEAN F. TERRY, L.L.A. (St. Andrews), 1913. _To Sir Francis Douglas Blake, this book is inscribed in admiration of an eminent Northumbrian._ CONTENTS. CHAPTER I.--The Coast of Northumberland CHAPTER II.--North and South Tyne CHAPTER III.--Down the Tyne CHAPTER IV.--Newcastle-upon-Tyne CHAPTER V.--Elswick and its Founder Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. CHAPTER VI.--The Cheviots CHAPTER VII.--The Roman Wall CHAPTER VIII.--Some Northumbrian Streams CHAPTER IX.--Drum and Trumpet CHAPTER X.--Tales and Legends CHAPTER XI.--Ballads and Poems ILLUSTRATIONS. BAMBURGH CASTLE (_From photograph by J.P. Gibson, Hexham_.) TYNEMOUTH PRIORY (_From photograph by T.H. Dickinson, Sheriff Hill_.) HEXHAM ABBEY FROM NORTH WEST (_From photograph by J.P. Gibson, Hexham_.) THE RIVER TYNE AT NEWCASTLE (_From photograph by T.H. Dickinson, Sheriff Hill_.) NEWCASTLE-UPON-TYNE NORTH GATEWAY, HOUSESTEADS, AND ROMAN WALL (_From photograph by J.P. -

PREFACE in Issuing in Book Form a Collection of Homely Songs And

PREFACE In issuing in book form a collection of homely songs and ballads (a few of which have already been favour- ably received), the writer has been persuaded to preface them with a short historical sketch of the district to which they mostly refer. The subject was so congenial and extensive that the narrative speedily attained to alar ming dimensions, and has only been reduced to its present size by a wholesale pruning, more heavy perhaps than judicious. The fortunes of the Gordons are so intimately bound up and associated with Strathb- ogie that the history of the Strath must be, to a great extent, a history of this powerful clan, whose actions have so materially influenced the destinies of Scotland. Reared amongst the expiring echoes of old-world legends and superstitions, and come of an old Strathbogie stock (e terra natu in their own opinion), who looked with something like reverence on a troubled but heroic past, the history and traditions of his native glen have always appeared invested with an extraordinary charm to the author, whose writing he would fain hope is in the spirit which animated the Strath with any preten- sions to the well-balanced accuracy of the unbiased historian. In the first chapter, from the want of sufficient data, probability must take the place of accuracy. When such eminent writers as Chalmers, Garnett, Taylor, Skene, Robertson, Forbes-Leslie, and Pinkerton differ so widely in their views regarding the Picts and their language, who will presume to decide? The preponder- ance of opinion certainly leans towards a Celtic extraction and tongue. -

Genealogical Memoirs of the Family of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. of Abbotsford

GENEALOGICAL MEMOIRS OF THE FAMILY OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, Bart, ETC., ETC. '«* BURIAL AISLE ANCESTORS, THE HALIBURT0N3 iR WALTER SCOTT AND OF HIS IN THE ABBEY OT DRYBURGH. GENEALOGICAL MEMOIRS OF THE FAMILY OF Sm WALTER SCOTT, Bart. OF ABBOTSrORD WITH A REPllINT OF HIS MEMOEIALS OF THE HALIBUETONS Rev. CHARLES ROGERS, LL.D. HISTORIOGEAPHER TO THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF QUEBEC, MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA, AND CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ENGLAND LONDON HOULSTON & SONS, PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1877 EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY M'FARLANE AND ERSKINE, ST JAMES SQUARE. PREFACE. Sm Walter Scott was ambitious of establishing a family which might perpetuate his name, in connection with that interesting spot on the banks of the Tweed which he had reclaimed and adorned. To be " founder of a distinct branch of the House of Scott," was, according to Mr Lockhart, " his first and last worldly ambition." "He desired," continues his biographer, " to plant a lasting root, and dreamt not of present fame, but of long distant generations rejoicing in the name of Scott of Abbotsford. By this idea, all his reveries, all his aspirations, all his plans and efforts, were shadowed and controlled. The great object and end only rose into clearer daylight, and swelled into more substantial dimensions, as public applause strengthened his confidence in his own powers and faculties ; and when he had reached the summit of universal and unrivalled honour, he clung to his first love with the faith of a Paladin." More clearly to appreciate why Sir Walter Scott was so powerfully influenced by the desire of founding a family, it is necessary to be acquainted with his relations to those who preceded him. -

Ayrshire, Its History and Historic Families

Hi HB|B| m NHiKB!HI RRb J National Library of Scotland ii minimi *B000052238* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland "http://www.archive.org/details/ayrshireitshisv21908robe AYRSHIRE BY THE SAME AUTHOR The Kings of Carrick. A Historical Romance of the Kennedys of Ayrshire ------- 5/- Historical Tales and Legends of Ayrshire - - 5/- The Lords of Cunningham. A Historical Romance of the Blood Feud of Eglinton and Glencairn - - 5/- Auld Ayr. A Study in Disappearing Men and Manners - - Net 3/6 The Dule Tree of Cassillis ... - Net 3/6 Historic Ayrshire. A Collection of Historical Works treating of the County of Ayr. Two Volumes - Net 20/- Old Ayrshire Days Net 4/6 AYRSHIRE Its History and Historic Families BY WILLIAM ROBERTSON VOLUME II Kilmarnock Dunlop & Drennan, "Standard" Office- Ayr Stephen & Pollock 1908 CONTENTS OF VOLUME II PAGE Introduction i I. The Kennedys of Cassillis and Culzean 3 II. The Montgomeries of Eglinton - - 43 III. The Boyles of Kelburn - - - 130 IV. The Dukedom of Portland - - - 188 V. The Marquisate of Bute - - - 207 VI. The Earldom of Loudoun ... 219 VII. The Dalrymples of Stair - - - 248 VIII. The Earldom of Glencairn - - - 289 IX. The Boyds of Kilmarnock - - - 329 X The Cochranes of Dundonald - - 368 XI. Hamilton, Lord Bargany - - - 395 XII. The Fergussons of Kilkerran - - 400 INTRODUCTION. The story of the Historic Families of Ayrshire is one of «xceptional interest, as well from the personal as from the county, as here and there from the national, standpoint. As one traces it along the centuries he realises, what it is sometimes difficult to do in a general historical survey, what sort of men they were who carried on the succession of events, and obtains many a glimpse into their own character that reveals their individuality and their idiosyncracies, as well as the motives that actuated and that animated them. -

Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads

THE CAUSE Francis James Child and William Macmath Working Together for Ballads Mary Ellen Brown• • , Editor Contents Acknowledgements The Cause The Letters Index Acknowledgments The letters between Francis James Child and William Macmath reproduced here belong to the permanent collections of the Houghton Library, Harvard University and the Hornel Library, Broughton House, Kirkcudbright, a National Trust for Scotland property. I gratefully acknowledge the help and hospitality given me by the staffs of both institutions and their willingness to allow me to make these materials more widely available. My visits to both facilities in search of data, transcribing hundreds of letters to bring home and analyze, was initially provided by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial and Andrew W. Mellon foundations and subsequently—for checking my transcriptions and gathering additional material--by the Office of the Provost for Research at Indiana University Bloomington. This serial support has made my work possible. Quite unexpectedly, two colleagues/friends met me the last time I was in Kirkcudbright (2014) and spent time helping me correct several difficult letters and sharing their own perspectives on these and other materials—John MacQueen and the late Ronnie Clark. Robert E. Lewis helped me transcribe more accurately Child’s reference and quotation from Chaucer; that help reminded me that many of the letters would benefit from copious explanatory notes in the future. Much earlier I benefitted from conversations with Sigrid Rieuwerts and throughout the research process with Emily Lyle. Both of their published and anticipated research touches on related publications as they have sought to explore and make known the rich past of Scots and the study of ballads. -

Otterburn Castle ~ History the HISTORY of OTTERBURN TOWER/CASTLE

Discover Relax Escape Otterburn Castle ~ History THE HISTORY OF OTTERBURN TOWER/CASTLE Origins - The D’Umphraville Family In 1076, in return for his services to his cousin, William the Conqueror, Robert D’Umphraville, was granted the liberty of Redesdale, which includes Otterburn, to hold and “keep free from wolves and enemies” for the king. In 1245 the demesne lands of the manor of Otterburn are listed as consisting of 168 acres of arable and 42 acres of meadow ground to which were attached a mill and cottages and land for ten bondagers. A survey commissioned by the king in 1308 revealed that the original Pele Tower at Otterburn was in existence. It was then described as a “capital messuage”. There was also a park stocked with “wild beasts”. So it would appear that the original tower was built between 1245 and 1308. A Pele Tower is a fortified structure peculiar to the English/Scottish border region. They were built, mainly in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries as a defense against raids. According to the Pease family, former owners of Otterburn Tower, the tower part of the building stands on the exact site of the original Pele, the original foundation walls of which can still be seen. The Battle of Otterburn - 1388 The Pele Tower features in old accounts of the 1388 Battle of Otterburn. An account of the battle was detailed by Froissart who describes how the Scottish tried to take the Tower while waiting for the English Lord Percy and his men. Their attack against Otterburn Tower began at dawn, but the Tower was “tolerably strong and situated amongst the marshes, they attacked so long and unsuccessfully that they were fatigued and therefore sounded a retreat.” That evening most of the Scottish Leaders wanted to return across the border but were overruled by Lord Douglas who still wished to take the Tower.