The WALLS of EDINBURGH, 1427 - 1764 Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Isles – Castles, Countrysides and Capitals Scotland • England • Wales • Ireland

12 DAY WORLD HOLIDAY British Isles – Castles, Countrysides and Capitals Scotland • England • Wales • Ireland September 10, 2020 Departure Date: British Isles – Castles, Countrysides and Capitals Discover the history and charms of the 12 Days • 15 Meals British Isles as you visit Scotland, England, Wales and Ireland. See historic royal castles, the beauty of England’s Lake District and Ireland’s countryside…you’ll experience it all on this journey through these four magnificent countries. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS 4 15 Meals (10 breakfasts and 5 dinners) 4 Airport transfers on tour dates when air is provided by Mayflower Cruises & Tours 4 Included visits to Edinburgh, Cardiff and Blarney Castles Experiene the beauty of the Cotswolds 4 Discover the capital cities of Edinburgh, Cardiff and Dublin on included guided tours DAY 1 – Depart the USA 4 Visit Gretna Green, ‘the marriage capital of the UK’ Depart the USA on your overnight flight to Edinburgh, Scotland, where 4 Relax aboard a scenic cruise on Lake Windermere in England’s centuries of history meet a vibrant, cosmopolitan city. famed Lake District 4 Tour the medieval town of York and visit the Minster 4 DAY 2 – Edinburgh, Scotland Tour the childhood home of William Shakespeare during the visit to Upon arrival, you’ll be met by a Mayflower representative and trans- Stratford-upon-Avon ferred to your hotel. The remainder of the day is at leisure to begin im- 4 Enjoy a scenic journey through the Cotswolds, one of England’s most mersing yourself in the Scottish culture. picturesque areas 4 Discover the ancient art of creating Waterford Crystal 4 DAY 3 – Edinburgh Kiss the Blarney Stone during the visit to Blarney Castle’s mysterious The day begins with an included tour of this capital city. -

Notices of the King's Master. Weights of Scotland, With

III. NOTICEE KING'TH F SO S MASTER. WEIGHT F SCOTLANDO S , WITH WRIT THEIF SO R APPOINTMENTS . MYLNEREVS E . R TH . Y B ., M.A., B.C.L. OXON. The King's Master Wright was a personage of less importance than the King's Master Mason or the King's Master of Work. Still, the history of his office resembles in many respects that of the two last- named officials, and we find him and his assistants mentioned from tim e earl timo th et yn ei record f Scotlando s e numbeTh . f wrighto r s in the royal employment seems to have varied considerably, according to e variouth s exigencie e Crownth f d theso s an ; e wrights could readily turn their hands to boat-building, the construction of instruments for military warfare, or the internal fittings of the Eoyal Palace. Some notices of the wrights and carpenters employed by the Kings of Scotlandin early times maybe Exchequerfoune th n di Rolls. Thus 129n ,i 0 Alexander Carpentere th , s wor,hi receiver k fo execute y spa Stirlinn di g Castle by the King's command. In 1361 Malcolm, the Wright, receives £10 fro e fermemth f Aberdeeno s d thian ,s payhien repeates i t laten di r years. Between the years 1362 and 1370 Sir William Dishington acted as Master of Work to the Church of St Monan's in Fife, and received from Kine Th g . alsOd of £613 . o pair 7s Kinm fo d, su ge Davith . II d carpenter's wor t thika s 137churcn I , 7. -

Church of Scotland Records Held by Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives

CHURCH OF SCOTLAND RECORDS HELD BY ABERDEEN CITY AND ABERDEENSHIRE ARCHIVES A GUIDE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i ABERDEEN PRESBYTERY RECORDS 1 ST NICHOLAS KIRK SESSION RECORDS 4 GREYFRIARS KIRK SESSION RECORDS 12 NIGG KIRK SESSION RECORDS 18 ABERDEEN SYNOD RECORDS 19 ST CLEMENTS KIRK SESSION 20 JOHN KNOX KIRK SESSION RECORDS 23 INTRODUCTION Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives holds various records relating to the Church of Scotland in Aberdeen. The records are held by Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives on behalf of the National Archives of Scotland under what is known as ‘Charge and Superintendence’. When the Church of Scotland deposited its records in Edinburgh, a decision was made that where there were suitable repositories, local records would be held in their area of origin. As a result, Aberdeen City and Aberdeenshire Archives was designated as a suitable repository and various records were returned to the city. Microfilm copies of the majority of the original volumes can be viewed in the National Archives in Edinburgh. All Church of Scotland records begin with the reference CH2 followed by the number allocated to that particular church. For example, St Nicholas is referenced 448, therefore the full reference number for the records of the St Nicholas Kirk Session is CH2/448 followed by the item number. If you wish to look at any of the records, please note the reference number (this always starts with CH2 for records relating to the Church of Scotland) and take care to ensure the record you wish to view covers the correct dates. You do not need to note the description of the item, only the reference, but please ensure you have identified the correct item. -

1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate's Close Proximity to The

Edinburgh Graveyards Project: Documentary Survey For Canongate Kirkyard --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Canongate 1.1. Background Canongate’s close proximity to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which is situated at the eastern end of Canongate Burgh, has been influential on both the fortunes of the Burgh and the establishment of Canongate Kirk. In 1687, King James VII declared that the Abbey Church of Holyroodhouse was to be used as the chapel for the re-established Order of the Thistle and for the performance of Catholic rites when the Royal Court was in residence at Holyrood. The nave of this chapel had been used by the Burgh of Canongate as a place of Protestant worship since the Reformation in the mid sixteenth century, but with the removal of access to the Abbey Church to practise their faith, the parishioners of Canongate were forced to find an alternative venue in which to worship. Fortunately, some 40 years before this edict by James VII, funds had been bequeathed to the inhabitants of Canongate to erect a church in the Burgh - and these funds had never been spent. This money was therefore used to build Canongate Kirk and a Kirkyard was laid out within its grounds shortly after building work commenced in 1688. 1 Development It has been ruminated whether interments may have occurred on this site before the construction of the Kirk or the landscaping of the Kirkyard2 as all burial rights within the church had been removed from the parishioners of the Canongate in the 1670s, when the Abbey Church had became the chapel of the King.3 The earliest known plan of the Kirkyard dates to 1765 (Figure 1), and depicts a rectilinear area on the northern side of Canongate burgh with arboreal planting 1 John Gifford et al., Edinburgh, The Buildings of Scotland: Pevsner Architectural Guides (London : Penguin, 1991). -

Written Guide

The tale of a tail A self-guided walk along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile ww.discoverin w gbrita in.o the stories of our rg lands discovered th cape rough w s alks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route map 5 Practical information 6 Commentary 8 Credits © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2015 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey Cover image: Detail from the Scottish Parliament Building © Rory Walsh RGS-IBG Discovering Britain 3 The tale of a tail Discover the stories along Edinburgh’s Royal Mile A 1647 map of The Royal Mile. Edinburgh Castle is on the left Courtesy of www.royal-mile.com Lined with cobbles and layered with history, Edinburgh’s ‘Royal Mile’ is one of Britain’s best-known streets. This famous stretch of Scotland’s capital also attracts visitors from around the world. This walk follows the Mile from historic Edinburgh Castle to the modern Scottish Parliament. The varied sights along the way reveal Edinburgh’s development from a dormant volcano into a modern city. Also uncover tales of kidnap and murder, a dramatic love story, and the dramatic deeds of kings, knights and spies. The walk was originally created in 2012. It was part of a series that explored how our towns and cities have been shaped for many centuries by some of the 206 participating nations in the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. -

Fact Sheet #1

State Papers Online Part II The Tudors: Henry VIII to Elizabeth I, 1509 – 1603: State Papers Foreign, Ireland, Scotland, Borders and Registers of the Privy Council State Papers Online, 1509-1714, is a groundbreaking new online resource for the study of Early Modern Britain and Europe. Spanning Part II Content: two centuries of the British monarchy in the 16th and 17th centuries the collection reunites State Papers Domestic and Foreign with the • 500,000 pages of manuscripts and images Registers of the Privy Council in The National Archives, Kew and • 230,000 Calendar entries the State Papers in the British Library. This unique online resource •Introductory essay by Dr Stephen Alford reproduces the original historical manuscripts in facsimile and links •Essays by leading scholars on key subjects each manuscript to its corresponding fully-searchable Calendar entry. with links to documents •Scanned facsimile images of State Papers Owing to the size of the collection - almost 2.2 million pages in •Searchable Calendars, transcriptions or total - State Papers Online is published in four parts. Parts I and II, hand lists combined, cover the complete State Papers for the whole of the •Key Documents – a selection of important Tudor period. Part III consists of the State Papers Domestic for documents for easy access the Stuart era. Part IV contains State Papers Foreign, Ireland and •Links to online palaeography and Latin Registers of the Privy Council and completes the collection courses •Research Tools including an Image Gallery of State Papers for the whole of the Stuart period. ' State Papers Online Part II: The Tudors: Henry VIII to Elizabeth I, 1509-1603: State Papers Foreign, Ireland, Scotland, Borders and Registers of the Privy Council ) Containing around 500,000 facsimile manuscript pages linking to fully-searchable Calendar entries, Part II reunites Foreign, Scotland, 2 Borders and Ireland papers for the 16th century together with the Registers (‘Minutes’) of the Privy Council for the whole of the Tudor period. -

The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate

Finlay, J. (2004) The early career of Thomas Craig, advocate. Edinburgh Law Review, 8 (3). pp. 298-328. ISSN 1364-9809 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/37849/ Deposited on: 02 April 2012 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk EdinLR Vol 8 pp 298-328 The Early Career of Thomas Craig, Advocate John Finlay* Analysis of the clients of the advocate and jurist Thomas Craig of Riccarton in a formative period of his practice as an advocate can be valuable in demonstrating the dynamics of a career that was to be noteworthy not only in Scottish but in international terms. However, it raises the question of whether Craig’s undoubted reputation as a writer has led to a misleading assessment of his prominence as an advocate in the legal profession of his day. A. INTRODUCTION Thomas Craig (c 1538–1608) is best known to posterity as the author of Jus Feudale and as a commissioner appointed by James VI in 1604 to discuss the possi- bility of a union of laws between England and Scotland.1 Following from the latter enterprise, he was the author of De Hominio (published in 1695 as Scotland”s * Lecturer in Law, University of Glasgow. The research required to complete this article was made possible by an award under the research leave scheme of the Arts and Humanities Research Board and the author is very grateful for this support. He also wishes to thank Dr Sharon Adams, Mr John H Ballantyne, Dr Julian Goodare and Mr W D H Sellar for comments on drafts of this article, the anonymous reviewer for the Edinburgh Law Review, and also the members of the Scottish Legal History Group to whom an early version of this paper was presented in October 2003. -

Post-Office Annual Directory

frt). i pee Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/postofficeannual182829edin n s^ 'v-y ^ ^ 9\ V i •.*>.' '^^ ii nun " ly Till [ lililiiilllliUli imnw r" J ifSixCtitx i\ii llatronase o( SIR DAVID WEDDERBURN, Bart. POSTMASTER-GENERAL FOR SCOTLAND. THE POST OFFICE ANNUAL DIRECTORY FOR 18^8-29; CONTAINING AN ALPHABETICAL LIST OF THE NOBILITY, GENTRY, MERCHANTS, AND OTHERS, WITH AN APPENDIX, AND A STREET DIRECTORY. TWENTY -THIRD PUBLICATION. EDINBURGH : ^.7- PRINTED FOR THE LETTER-CARRIERS OF THE GENERAL POST OFFICE. 1828. BALLAN'fVNK & CO. PRINTKBS. ALPHABETICAL LIST Mvtt% 0quaxt&> Pates, kt. IN EDINBURGH, WITH UEFERENCES TO THEIR SITUATION. Abbey-Hill, north of Holy- Baker's close, 58 Cowgate rood Palace BaUantine's close, 7 Grassmrt. Abercromby place, foot of Bangholm, Queensferry road Duke street Bangholm-bower, nearTrinity Adam square. South Bridge Bank street, Lawnmarket Adam street, Pleasance Bank street, north, Mound pi. Adam st. west, Roxburgh pi. to Bank street Advocate's close, 357 High st. Baron Grant's close, 13 Ne- Aird's close, 139 Grassmarket ther bow Ainslie place, Great Stuart st. Barringer's close, 91 High st. Aitcheson's close, 52 West port Bathgate's close, 94 Cowgate Albany street, foot of Duke st. Bathfield, Newhaven road Albynplace, w.end of Queen st Baxter's close, 469 Lawnmar- Alison's close, 34 Cowgate ket Alison's square. Potter row Baxter's pi. head of Leith walk Allan street, Stockbridge Beaumont place, head of Plea- Allan's close, 269 High street sance and Market street Bedford street, top of Dean st. -

Cost Effective with Fit

SALTIRE COURT 20 CASTLE TERRACE EDINBURGH Cost effective GRADE A OFFICES with fit out Saltire Court is located in Edinburgh’s Castle Terrace public car park is directly opposite Exchange District, adjacent to Edinburgh the building and discounted rates are available. Location Castle and Princes Street Gardens. This is a It is one of the most prestigious and well known prime office location close to bus, rail and buildings in Edinburgh and occupiers include KPMG, Deloitte, Shoosmiths and Close Brothers. tram links together with retail and leisure Dine is a fine dining restaurant located in the amenities on Lothian Road and Princes Street. development and there is also a coffee shop. Waverley Rail Station The Meadows Quartermile Edinburgh Castle St Andrew Square Bus Terminus Castle Terrace Codebase Car Park Lothian Road Princes Street Gardens George Street Usher Hall Edinburgh International The Principal Conference Centre Charlotte Square Princes Street Saltire Court Sheraton Grand Hotel & Spa Charlotte Square Waldorf Astoria Tram Line Haymarket station (5 mins) Description Saltire Court is a prime Grade A office building and the large entrance has an outlook to Edinburgh Castle. The building offers a concierge style reception and there are large break out areas within the common parts available to all occupiers. The ground floor office is accessed directly from the reception and is a prominent suite. The lower ground floor can be accessed via a feature stair or lifts. The first floor is accessed from the building’s main lift core or feature stair. All suites have windows on to Castle Terrace. The specification includes: • LED Lighting • Metal suspended ceiling • Air-conditioning • Self contained toilets The space can be offered with the benefit of the high quality fit out or refurbished. -

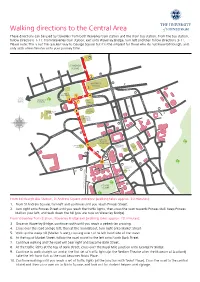

Walking Directions to the Central Area These Directions Can Be Used by Travellers from Both Waverley Train Station and the Main Bus Station

Walking directions to the Central Area These directions can be used by travellers from both Waverley train station and the main bus station. From the bus station, follow directions 1-11. From Waverley train station, exit onto Waverley Bridge, turn left and then follow directions 3-11. Please note: This is not the quickest way to George Square but it is the simplest for those who do not know Edinburgh, and only adds a few minutes onto your journey time. 1 ST ANDREW T S SQUARE H T I E L HANOVER ST 2 FREDERICK ST PRINCES ST GEORGE ST W A V WAVERLEY NORTH BRIDGE E P R L STATION E Y 3 B R JEFFREY ST PRINCES ST I D G ART E GALLERIES 5 4 COCKBURN ST TO THE N ST MARY’S ST ST JOHN ST O CANONGATE WESTERN 6 MARKET ST PRINCES ST RT CITY GENERAL GARDENS H BAN 7 K ST BANK ST CHAMBERS P HIGH ST (ROYAL MILE) 8 ST GILES EDINBURGH CATHEDRAL HOLYROOD ROAD CASTLE SOUTH BRIDGE P NATIONAL LIBRARY OF GEORGE IV BRIDGE T SCOTLAND S N A I R COWGATE P O T T S L E C Y I R A A V M FIR S IN A N C CANDLEMAKER ROW E T ST GRASSMARKET RS S ND MBE MO HA RUM C NATIONAL D MUSEUM OF SCOTLAND R GREYFRIARS 9 PEDESTRIAN SURGEON’S IC P UNDERPASS H KIRK O HALL M NICOLSON ST T FESTIVAL O WEST PORT T T THEATRE N S E D FORREST ROAD FORREST R N B P A R R I L I O S H A T T W HILL PLACE C LADY LAWSON STREET O O E PL L E RICHMOND LANE AC PL 10 BRISTO IOT TEV SQUARE EDINBURGH MIDDLE MEADOW WALK CENTRAL LAURISTON PLACE MOSQUE P D A V I E S CRICHTON ST W. -

Building Stones of Edinburgh's South Side

The route Building Stones of Edinburgh’s South Side This tour takes the form of a circular walk from George Square northwards along George IV Bridge to the High Street of the Old Town, returning by South Bridge and Building Stones Chambers Street and Nicolson Street. Most of the itinerary High Court 32 lies within the Edinburgh World Heritage Site. 25 33 26 31 of Edinburgh’s 27 28 The recommended route along pavements is shown in red 29 24 30 34 on the diagram overleaf. Edinburgh traffic can be very busy, 21 so TAKE CARE; cross where possible at traffic light controlled 22 South Side 23 crossings. Public toilets are located in Nicolson Square 20 19 near start and end of walk. The walk begins at NE corner of Crown Office George Square (Route Map locality 1). 18 17 16 35 14 36 Further Reading 13 15 McMillan, A A, Gillanders, R J and Fairhurst, J A. 1999 National Museum of Scotland Building Stones of Edinburgh. 2nd Edition. Edinburgh Geological Society. 12 11 Lothian & Borders GeoConservation leaflets including Telfer Wall Calton Hill, and Craigleith Quarry (http://www. 9 8 Central 7 Finish Mosque edinburghgeolsoc.org/r_download.html) 10 38 37 Quartermile, formerly 6 CHAP the Royal Infirmary of Acknowledgements. 1 EL Edinburgh S T Text: Andrew McMillan and Richard Gillanders with Start . 5 contributions from David McAdam and Alex Stark. 4 2 3 LACE CLEUCH P Map adapted with permission from The Buildings of BUC Scotland: Edinburgh (Pevsner Architectural Guides, Yale University Press), by J. Gifford, C. McWilliam and D. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians)