Supplemental Materials Figure 1. 80 Genes Most Highly Differentially Expressed Comparing Dedifferentiated to Well- Differentiated Liposarcoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancer Immunity (1 December 2006) Vol

Cancer Immun 1424-9634Academy of Cancer Immunology Cancer Immunity (1 December 2006) Vol. 6, p. 12 Submitted: 26 September 2006. Accepted: 10 October 2006. Copyright © 2006 by Andrew J. G. Simpson 061012 Article Physical interaction of two cancer-testis antigens, MAGE-C1 (CT7) and NY-ESO-1 (CT6) Hearn J. Cho1*,**, Otavia L. Caballero2*, Sacha Gnjatic2, Valéria C. C. Andrade3, Gisele W. Colleoni3, Andre L. Vettore4, Hasina H. Outtz1, Sheila Fortunato2, Nasser Altorki1, Cathy A. Ferrera1, Ramon Chua2, Achim A. Jungbluth2, Yao-Tseng Chen1, Lloyd J. Old2 and Andrew J. G. Simpson2 1Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 1300 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021, USA 2Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, New York Branch at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021, USA 3Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil 4Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Sao Paulo Branch, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil *These authors contributed equally to this work **Present address: NYU Cancer Institute, New York University School of Medicine, 550 First Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA Contributed by: LJ Old Cancer/testis (CT) antigens are the protein products of germ line- encoded on the X chromosome (CT-X antigens) and those that associated genes that are activated in a wide variety of tumors and can are not (non-X CT antigens) (1). elicit autologous cellular and humoral immune responses. CT It is estimated that 10% of the genes on the X-chromosome antigens can be divided between those that are encoded on the X belong to CT-X families (5). -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Expression of Cancer-Testis Antigens MAGEA1, MAGEA3, ACRBP, PRAME, SSX2, and CTAG2 in Myxoid and Round Cell Liposarcoma

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, 1238–1245 1238 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 Expression of cancer-testis antigens MAGEA1, MAGEA3, ACRBP, PRAME, SSX2, and CTAG2 in myxoid and round cell liposarcoma Jessica A Hemminger1, Amanda Ewart Toland2, Thomas J Scharschmidt3, Joel L Mayerson3, Denis C Guttridge2 and O Hans Iwenofu1 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Wexner Medical Center at The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; 2Department of Molecular Virology, Immunology and Medical Genetics, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA and 3Department of Orthopedics, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA Myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma is a frequently encountered liposarcoma subtype. The mainstay of treatment remains surgical excision with or without chemoradiation. However, treatment options are limited in the setting of metastatic disease. Cancer-testis antigens are immunogenic antigens with the expression largely restricted to testicular germ cells and various malignancies, making them attractive targets for cancer immunotherapy. Gene expression studies have reported the expression of various cancer-testis antigens in liposarcoma, with mRNA expression of CTAG1B, CTAG2, MAGEA9, and PRAME described specifically in myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma. Herein, we further explore the expression of the cancer-testis antigens MAGEA1, ACRBP, PRAME, and SSX2 in myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma by immunohistochemistry in addition to determining mRNA levels of CTAG2 (LAGE-1), PRAME, and MAGEA3 by quantitative real-time PCR. Samples in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks (n ¼ 37) and frozen tissue (n ¼ 8) were obtained for immunohistochemistry and quantitative real-time PCR, respectively. Full sections were stained with antibodies to MAGEA1, ACRBP, PRAME, and SSX2 and staining was assessed for intensity (1–2 þ ) and percent tumor positivity. -

The Capacity of Long-Term in Vitro Proliferation of Acute Myeloid

The Capacity of Long-Term in Vitro Proliferation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells Supported Only by Exogenous Cytokines Is Associated with a Patient Subset with Adverse Outcome Annette K. Brenner, Elise Aasebø, Maria Hernandez-Valladares, Frode Selheim, Frode Berven, Ida-Sofie Grønningsæter, Sushma Bartaula-Brevik and Øystein Bruserud Supplementary Material S2 of S31 Table S1. Detailed information about the 68 AML patients included in the study. # of blasts Viability Proliferation Cytokine Viable cells Change in ID Gender Age Etiology FAB Cytogenetics Mutations CD34 Colonies (109/L) (%) 48 h (cpm) secretion (106) 5 weeks phenotype 1 M 42 de novo 241 M2 normal Flt3 pos 31.0 3848 low 0.24 7 yes 2 M 82 MF 12.4 M2 t(9;22) wt pos 81.6 74,686 low 1.43 969 yes 3 F 49 CML/relapse 149 M2 complex n.d. pos 26.2 3472 low 0.08 n.d. no 4 M 33 de novo 62.0 M2 normal wt pos 67.5 6206 low 0.08 6.5 no 5 M 71 relapse 91.0 M4 normal NPM1 pos 63.5 21,331 low 0.17 n.d. yes 6 M 83 de novo 109 M1 n.d. wt pos 19.1 8764 low 1.65 693 no 7 F 77 MDS 26.4 M1 normal wt pos 89.4 53,799 high 3.43 2746 no 8 M 46 de novo 26.9 M1 normal NPM1 n.d. n.d. 3472 low 1.56 n.d. no 9 M 68 MF 50.8 M4 normal D835 pos 69.4 1640 low 0.08 n.d. -

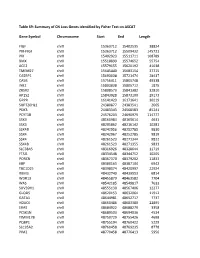

Table S9: Summary of CN Loss Genes Identified by Fisher Test on ASCAT

Table S9: Summary of CN Loss Genes identified by Fisher Test on ASCAT Gene Symbol Chromosome Start End Length FIGF chrX 15363712 15402535 38824 PIR-FIGF chrX 15363712 15509432 145721 PIR chrX 15402923 15511711 108789 BMX chrX 15518899 15574652 55754 ACE2 chrX 15579155 15620192 41038 TMEM27 chrX 15645440 15683154 37715 CA5BP1 chrX 15693038 15721474 28437 CA5B chrX 15756411 15805748 49338 INE2 chrX 15803838 15805712 1875 ZRSR2 chrX 15808573 15841382 32810 AP1S2 chrX 15843928 15873100 29173 GRPR chrX 16141423 16171641 30219 SUPT20HL1 chrX 24380877 24383541 2665 PDK3 chrX 24483343 24568583 85241 PCYT1B chrX 24576203 24690979 114777 SSX9 chrX 48160984 48165614 4631 SSX3 chrX 48205862 48216142 10281 SSX4B chrX 48242956 48252785 9830 SSX4 chrX 48242967 48252785 9819 SSX4 chrX 48261523 48271344 9822 SSX4B chrX 48261523 48271355 9833 SLC38A5 chrX 48316926 48328644 11719 FTSJ1 chrX 48334548 48344752 10205 PORCN chrX 48367370 48379202 11833 EBP chrX 48380163 48387104 6942 TBC1D25 chrX 48398074 48420997 22924 RBM3 chrX 48432740 48439553 6814 WDR13 chrX 48455879 48463582 7704 WAS chrX 48542185 48549817 7633 SUV39H1 chrX 48555130 48567406 12277 GLOD5 chrX 48620153 48632064 11912 GATA1 chrX 48644981 48652717 7737 HDAC6 chrX 48660486 48683380 22895 ERAS chrX 48684922 48688279 3358 PCSK1N chrX 48689503 48694036 4534 TIMM17B chrX 48750729 48755426 4698 PQBP1 chrX 48755194 48760422 5229 SLC35A2 chrX 48760458 48769235 8778 PIM2 chrX 48770458 48776413 5956 OTUD5 chrX 48779302 48815648 36347 KCND1 chrX 48818638 48828251 9614 GRIPAP1 chrX 48830133 48858675 28543 -

NY-ESO-1 (CTAG1B) Expression in Mesenchymal Tumors

Modern Pathology (2015) 28, 587–595 & 2015 USCAP, Inc. All rights reserved 0893-3952/15 $32.00 587 NY-ESO-1 (CTAG1B) expression in mesenchymal tumors Makoto Endo1,2,7, Marieke A de Graaff3,7, Davis R Ingram4, Simin Lim1, Dina C Lev4, Inge H Briaire-de Bruijn3, Neeta Somaiah5, Judith VMG Bove´e3, Alexander J Lazar6 and Torsten O Nielsen1 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; 2Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan; 3Department of Pathology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands; 4Department of Surgical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA; 5Department of Sarcoma Medical Oncology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA and 6Department of Pathology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1 (NY-ESO-1, CTAG1B) is a cancer-testis antigen and currently a focus of several targeted immunotherapeutic strategies. We performed a large-scale immunohistochemical expression study of NY-ESO-1 using tissue microarrays of mesenchymal tumors from three institutions in an international collaboration. A total of 1132 intermediate and malignant and 175 benign mesenchymal lesions were enrolled in this study. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on tissue microarrays using a monoclonal antibody for NY-ESO-1. Among mesenchymal tumors, myxoid liposarcomas showed the highest positivity for NY-ESO-1 (88%), followed by synovial sarcomas (49%), myxofibrosarcomas (35%), and conventional chondrosarcomas (28%). Positivity of NY-ESO-1 in the remaining mesenchymal tumors was consistently low, and no immunoreactivity was observed in benign mesenchymal lesions. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

G PROTEIN-COUPLED RECEPTORS Overview:- The completion of the Human Genome Project allowed the identification of a large family of proteins with a common motif of seven groups of 20-24 hydrophobic amino acids arranged as α-helices. Approximately 800 of these seven transmembrane (7TM) receptors have been identified of which over 300 are non-olfactory receptors (see Frederikson et al., 2003; Lagerstrom and Schioth, 2008). Subdivision on the basis of sequence homology allows the definition of rhodopsin, secretin, adhesion, glutamate and Frizzled receptor families. NC-IUPHAR recognizes Classes A, B, and C, which equate to the rhodopsin, secretin, and glutamate receptor families. The nomenclature of 7TM receptors is commonly used interchangeably with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR), although the former nomenclature recognises signalling of 7TM receptors through pathways not involving G proteins. For example, adiponectin and membrane progestin receptors have some sequence homology to 7TM receptors but signal independently of G-proteins and appear to reside in membranes in an inverted fashion compared to conventional GPCR. Additionally, the NPR-C natriuretic peptide receptor has a single transmembrane domain structure, but appears to couple to G proteins to generate cellular responses. The 300+ non-olfactory GPCR are the targets for the majority of drugs in clinical usage (Overington et al., 2006), although only a minority of these receptors are exploited therapeutically. Signalling through GPCR is enacted by the activation of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins (G proteins), made up of α, β and γ subunits, where the α and βγ subunits are responsible for signalling. The α subunit (tabulated below) allows definition of one series of signalling cascades and allows grouping of GPCRs to suggest common cellular, tissue and behavioural responses. -

Gene Expression Profiling Using Nanostring Digital RNA Counting to Identify Potential Target Antigens for Melanoma Immunotherapy

Published OnlineFirst September 10, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1253 Clinical Cancer Human Cancer Biology Research Gene Expression Profiling using Nanostring Digital RNA Counting to Identify Potential Target Antigens for Melanoma Immunotherapy Rachel E. Beard, Daniel Abate-Daga, Shannon F. Rosati, Zhili Zheng, John R. Wunderlich, Steven A. Rosenberg, and Richard A. Morgan Abstract Purpose: The success of immunotherapy for the treatment of metastatic cancer is contingent on the identification of appropriate target antigens. Potential targets must be expressed on tumors but show restricted expression on normal tissues. To maximize patient eligibility, ideal target antigens should be expressed on a high percentage of tumors within a histology and, potentially, in multiple different malignancies. Design: A Nanostring probeset was designed containing 97 genes, 72 of which are considered potential candidate genes for immunotherapy. Five established melanoma cell lines, 59 resected metastatic mela- noma tumors, and 31 normal tissue samples were profiled and analyzed using Nanostring technology. Results: Of the 72 potential target genes, 33 were overexpressed in more than 20% of studied melanoma tumor samples. Twenty of those genes were identified as differentially expressed between normal tissues and tumor samples by ANOVA analysis. Analysis of normal tissue gene expression identified seven genes with limited normal tissue expression that warrant further consideration as potential immunotherapy target antigens: CSAG2, MAGEA3, MAGEC2, IL13RA2, PRAME, CSPG4, and SOX10. These genes were highly overexpressed on a large percentage of the studied tumor samples, with expression in a limited number of normal tissue samples at much lower levels. Conclusion: The application of Nanostring RNA counting technology was used to directly quantitate the gene expression levels of multiple potential tumor antigens. -

Seromic Profiling of Ovarian and Pancreatic Cancer

Seromic profiling of ovarian and pancreatic cancer Sacha Gnjatica,1, Erika Rittera, Markus W. Büchlerb, Nathalia A. Gieseb, Benedikt Brorsc, Claudia Freid, Anne Murraya, Niels Halamad, Inka Zörnigd, Yao-Tseng Chene, Christopher Andrewsf, Gerd Rittera, Lloyd J. Olda,1, Kunle Odunsig,2, and Dirk Jägerd,2 aLudwig Institute for Cancer Research Ltd, Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065; bDepartment of General Surgery, cDepartment of Theoretical Bioinformatics, and dMedizinische Onkologie, Nationales Centrum für Tumorerkrankungen, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg D-69120, Germany; eDepartment of Pathology, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, New York, NY 10065; and fDepartment of Biostatistics and gDepartment of Gynecologic Oncology, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY 14263 Contributed by Lloyd J. Old, December 10, 2009 (sent for review August 20, 2009) Autoantibodies, a hallmark of both autoimmunity and cancer, analyzing a series of lung cancer and healthy control sera on a represent an easily accessible surrogate for measuring adaptive small array (329 proteins) for antigen reactivity using this anti- immune responses to cancer. Sera can now be assayed for re- body profiling method, referred to here as “seromics,” we were activity against thousands of proteins using microarrays, but there able to detect known antigens with sensitivity and specificity is no agreed-upon standard to analyze results. We developed a set comparable to ELISA, as well as new antigens that are now of tailored quality control and normalization procedures based on under further investigation. Contrary to gene microarrays where ELISA validation to allow patient comparisons and determination changes in the pattern of gene expression are detected in clus- of individual cutoffs for specificity and sensitivity. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

Genome-Wide Analysis of DNA Methylation, Copy Number Variation, and Gene Expression in Monozygotic Twins Discordant for Primary Biliary Cirrhosis

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation, copy number variation, and gene expression in monozygotic twins discordant for primary biliary cirrhosis. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/34d4m5nk Journal Frontiers in immunology, 5(MAR) ISSN 1664-3224 Authors Selmi, Carlo Cavaciocchi, Francesca Lleo, Ana et al. Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00128 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 28 March 2014 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00128 Genome-wide analysis of DNA methylation, copy number variation, and gene expression in monozygotic twins discordant for primary biliary cirrhosis Carlo Selmi 1,2*, Francesca Cavaciocchi 1,3, Ana Lleo4, Cristina Cheroni 5, Raffaele De Francesco5, Simone A. Lombardi 1, Maria De Santis 1,3, Francesca Meda1, Maria Gabriella Raimondo1, Chiara Crotti 1, Marco Folci 1, Luca Zammataro1, Marlyn J. Mayo6, Nancy Bach7, Shinji Shimoda8, Stuart C. Gordon9, Monica Miozzo10,11, Pietro Invernizzi 4, Mauro Podda1, Rossana Scavelli 5, Michelle R. Martin12, Michael F. Seldin13,14, Janine M. LaSalle 12 and M. Eric Gershwin2 1 Division of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Milan, Italy 2 Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Clinical Immunology, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA, USA 3 BIOMETRA Department, University of Milan, Milan, Italy 4 Liver Unit and Center for Autoimmune Liver Diseases, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, Milan, Italy 5 National Institute of Molecular Genetics (INGM), Milan, Italy 6 University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX, USA 7 Mt. Sinai University, NewYork, NY, USA 8 Clinical Research Center, National Nagasaki Medical Center, Nagasaki, Japan 9 Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI, USA 10 Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, Milan, Italy 11 Division of Pathology, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy 12 Genome Center and M.I.N.D. -

Downloaded 18 July 2014 with a 1% False Discovery Rate (FDR)

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0t47b9ws Author Spiciarich, David Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer by David Spiciarich A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Co-Chair Professor David E. Wemmer, Co-Chair Professor Matthew B. Francis Professor Amy E. Herr Fall 2017 Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer © 2017 by David Spiciarich Abstract Chemical glycoproteomics for identification and discovery of glycoprotein alterations in human cancer by David Spiciarich Doctor of Philosophy in Chemistry University of California, Berkeley Professor Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Co-Chair Professor David E. Wemmer, Co-Chair Changes in glycosylation have long been appreciated to be part of the cancer phenotype; sialylated glycans are found at elevated levels on many types of cancer and have been implicated in disease progression. However, the specific glycoproteins that contribute to cell surface sialylation are not well characterized, specifically in bona fide human cancer. Metabolic and bioorthogonal labeling methods have previously enabled enrichment and identification of sialoglycoproteins from cultured cells and model organisms. The goal of this work was to develop technologies that can be used for detecting changes in glycoproteins in clinical models of human cancer.