NY-ESO-1 (CTAG1B) Expression in Mesenchymal Tumors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cancer Immunity (1 December 2006) Vol

Cancer Immun 1424-9634Academy of Cancer Immunology Cancer Immunity (1 December 2006) Vol. 6, p. 12 Submitted: 26 September 2006. Accepted: 10 October 2006. Copyright © 2006 by Andrew J. G. Simpson 061012 Article Physical interaction of two cancer-testis antigens, MAGE-C1 (CT7) and NY-ESO-1 (CT6) Hearn J. Cho1*,**, Otavia L. Caballero2*, Sacha Gnjatic2, Valéria C. C. Andrade3, Gisele W. Colleoni3, Andre L. Vettore4, Hasina H. Outtz1, Sheila Fortunato2, Nasser Altorki1, Cathy A. Ferrera1, Ramon Chua2, Achim A. Jungbluth2, Yao-Tseng Chen1, Lloyd J. Old2 and Andrew J. G. Simpson2 1Weill Medical College of Cornell University, 1300 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021, USA 2Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, New York Branch at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 1275 York Avenue, New York, NY 10021, USA 3Escola Paulista de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil 4Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Sao Paulo Branch, Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil *These authors contributed equally to this work **Present address: NYU Cancer Institute, New York University School of Medicine, 550 First Avenue, New York, NY 10016, USA Contributed by: LJ Old Cancer/testis (CT) antigens are the protein products of germ line- encoded on the X chromosome (CT-X antigens) and those that associated genes that are activated in a wide variety of tumors and can are not (non-X CT antigens) (1). elicit autologous cellular and humoral immune responses. CT It is estimated that 10% of the genes on the X-chromosome antigens can be divided between those that are encoded on the X belong to CT-X families (5). -

Mixed Hepatoblastoma in the Adult: Case Report and Review of the Literature

J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.33.11.1058 on 1 November 1980. Downloaded from J Clin Pathol 1980;33:1058-1063 Mixed hepatoblastoma in the adult: case report and review of the literature RP HONAN AND MT HAQQANI From the Department of Pathology, Walton Hospital, Rice Lane, Liverpool L9 JAE, UK SUMMARY A case of mixed hepatoblastoma in a woman is described. A survey of the English literature reveals 13 cases acceptable as mixed hepatoblastoma; these have been described and published under a variety of names. Difficulties in nomenclature and the histology of these cases are discussed. Diagnosis depends on the identification of both malignant mesenchymal and malignant epithelial elements. The former include myxoid connective tissue resembling primitive mesenchyme and areas resembling adult fibrosarcoma. Mature fibrous tissue with calcification and bone for- mation may be seen. Epithelial areas show tissue resembling fetal liver, poorly differentiated epithelial cells, and/or areas of adenocarcinoma. The current view on histogenesis is also given. Most hepatoblastomas occur in children under the mixedtumour,6carcino-osteochondromyxosarcoma,5 copyright. age of 2 years.' Hepatoblastoma in adults is ex- and rhabdomyosarcohepatoma.7 tremely rare, and the prognosis is much worse than in the mixed hepatoblastoma of childhood. Case report The literature of mixed hepatoblastoma in adults has until recently been confused, and the true inci- CLINICAL PRESENTATION dence of the tumour obscured, owing to the various A Chinese woman aged 27 had been resident in names used by different authors to describe their England for eight years. She gave a history of cases. The commonest pseudonym is 'mixed malig- 18 months' intermittent right-sided chest pain http://jcp.bmj.com/ nant tumour',2-4 an ambivalent term which merely and upper abdominal discomfort. -

Supplemental Materials Figure 1. 80 Genes Most Highly Differentially Expressed Comparing Dedifferentiated to Well- Differentiated Liposarcoma

Supplemental Materials Figure 1. 80 genes most highly differentially expressed comparing dedifferentiated to well- differentiated liposarcoma Figure 2. Validation of microa CDC2, RACGAP1, FGFR-2, MAD2 and CITED1 200 CDK4 by Liposarcoma Subtype 16 0 12 0 80 Expression40 Level 0 Nl Fat rray data by quantitative RT-P Well Diff 16 0 p16 by Liposarcoma Subtype Dediff 12 0 80 Myxoid Expression40 Level Round Cell 0 12 0 MDM2 by Liposarcoma Subtype 10 0 Pleomorphic Nl Fat 80 60 40 Expression Level 20 RACGAP1 by LiposarcomaWell Diff Subtype 0 70 CR for genes CDK4, MDM2, p16, 60 Dediff 50 Nl Fat 40 30 Myxoid Expression20 Level Well Diff 10 50 0 Round Cell CDC2 by Liposarcoma Subtype Dediff 40 Nl Fat Pleomorphic 30 Myxoid 20 Expression Level Well Diff 10 MAD2L1 by Liposarcoma Subtype Round Cell 60 0 50 Dediff Pleomorphic 40 Nl Fat 30 Myxoid 20 Expression Level Well Diff 10 FGFR-2 by Liposarcoma Subtype 0 Round Cell 200 16 0 Dediff Nl Fat Pleomorphic 12 0 Myxoid 80 Expression Level Well Diff 40 Round Cell 0 Dediff Pleomorphic Nl Fat Myxoid Well Diff CITED1 by Liposarcoma Subtype Round Cell 10 0 80 Dediff Pleomorphic 60 40 Myxoid Expression Level 20 0 Round Cell Nl Fat Pleomorphic Well Diff Dediff Myxoid Round Cell Pleomorphic Table 1. 142 Gene classifier for liposarcoma subtype The genes used for each pair wise subtype comparison are grouped together. The flag column indicates which genes are unique to each subtype comparison. The values show the mean expression levels (actually the mean of the log expression levels was computed and than transformed back to absolute expression level). -

PROPOSED REGULATION of the STATE BOARD of HEALTH LCB File No. R057-16

PROPOSED REGULATION OF THE STATE BOARD OF HEALTH LCB File No. R057-16 Section 1. Chapter 457 of NAC is hereby amended by adding thereto the following provision: 1. The Division may impose an administrative penalty of $5,000 against any person or organization who is responsible for reporting information on cancer who violates the provisions of NRS 457. 230 and 457.250. 2. The Division shall give notice in the manner set forth in NAC 439.345 before imposing any administrative penalty 3. Any person or organization upon whom the Division imposes an administrative penalty pursuant to this section may appeal the action pursuant to the procedures set forth in NAC 439.300 to 439. 395, inclusive. Section 2. NAC 457.010 is here by amended to read as follows: As used in NAC 457.010 to 457.150, inclusive, unless the context otherwise requires: 1. “Cancer” has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 457.020. 2. “Division” means the Division of Public and Behavioral Health of the Department of Health and Human Services. 3. “Health care facility” has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 457.020. 4. “[Malignant neoplasm” means a virulent or potentially virulent tumor, regardless of the tissue of origin. [4] “Medical laboratory” has the meaning ascribed to it in NRS 652.060. 5. “Neoplasm” means a virulent or potentially virulent tumor, regardless of the tissue of origin. 6. “[Physician] Provider of health care” means a [physician] provider of health care licensed pursuant to chapter [630 or 633] 629.031 of NRS. 7. “Registry” means the office in which the Chief Medical Officer conducts the program for reporting information on cancer and maintains records containing that information. -

Non-Wilms Renal Cell Tumors in Children

PEDIATRIC UROLOGIC ONCOLOGY 0094-0143/00 $15.00 + .OO NON-WILMS’ RENAL TUMORS IN CHILDREN Bruce Broecker, MD Renal tumors other than Wilms’ tumor are tastases occur in 40% to 60% of patients with infrequent in childhood. Wilms’ tumors ac- clear cell sarcoma of the kidney, whereas they count for 6% to 7% of childhood cancer, are found in less than 2% of patients with whereas the remaining renal tumors account Wilms’ tumor.**,26 This distinct clinical behav- for less than l%.27The most common non- ior is one of the features that has led to its Wilms‘ tumors are clear cell sarcoma of the designation as a separate tumor. Other clini- kidney, rhabdoid tumor of the kidney (both cal features include a lack of association with formerly considered unfavorable Wilms’ tu- sporadic aniridia or hemihypertrophy. mor variants but now considered separate tu- Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney has not mors), renal cell carcinoma, mesoblastic been reported to occur bilaterally and is not nephroma, and multilocular cystic nephroma. associated with nephroblastomatosis. It has Collectively, these tumors account for less been reported in infancy and adulthood, but than 10% of the primary renal neoplasms in the peak incidence is between 3 and 5 years childhood. of age. It has an aggressive behavior that responds poorly to treatment with vincristine and actinomycin alone, leading to its original CLEAR CELL SARCOMA designation by Beckwith as an unfavorable histology pattern. The addition of doxorubi- Clear cell sarcoma of the kidney is cur- cin in aggressive chemotherapy regimens has rently considered a separate tumor distinct improved outcome. -

Expression of Cancer-Testis Antigens MAGEA1, MAGEA3, ACRBP, PRAME, SSX2, and CTAG2 in Myxoid and Round Cell Liposarcoma

Modern Pathology (2014) 27, 1238–1245 1238 & 2014 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/14 $32.00 Expression of cancer-testis antigens MAGEA1, MAGEA3, ACRBP, PRAME, SSX2, and CTAG2 in myxoid and round cell liposarcoma Jessica A Hemminger1, Amanda Ewart Toland2, Thomas J Scharschmidt3, Joel L Mayerson3, Denis C Guttridge2 and O Hans Iwenofu1 1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Wexner Medical Center at The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; 2Department of Molecular Virology, Immunology and Medical Genetics, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA and 3Department of Orthopedics, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH, USA Myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma is a frequently encountered liposarcoma subtype. The mainstay of treatment remains surgical excision with or without chemoradiation. However, treatment options are limited in the setting of metastatic disease. Cancer-testis antigens are immunogenic antigens with the expression largely restricted to testicular germ cells and various malignancies, making them attractive targets for cancer immunotherapy. Gene expression studies have reported the expression of various cancer-testis antigens in liposarcoma, with mRNA expression of CTAG1B, CTAG2, MAGEA9, and PRAME described specifically in myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma. Herein, we further explore the expression of the cancer-testis antigens MAGEA1, ACRBP, PRAME, and SSX2 in myxoid and round-cell liposarcoma by immunohistochemistry in addition to determining mRNA levels of CTAG2 (LAGE-1), PRAME, and MAGEA3 by quantitative real-time PCR. Samples in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks (n ¼ 37) and frozen tissue (n ¼ 8) were obtained for immunohistochemistry and quantitative real-time PCR, respectively. Full sections were stained with antibodies to MAGEA1, ACRBP, PRAME, and SSX2 and staining was assessed for intensity (1–2 þ ) and percent tumor positivity. -

Novel KHDRBS1-NTRK3 Rearrangement in a Congenital Pediatric CD34-Positive Skin Tumor: a Case Report

Virchows Archiv (2019) 474:111–115 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-018-2415-0 BRIEF REPORT Novel KHDRBS1-NTRK3 rearrangement in a congenital pediatric CD34-positive skin tumor: a case report Matthias Tallegas1 & Sylvie Fraitag2 & Aurélien Binet3 & Daniel Orbach4 & Anne Jourdain5 & Stéphanie Reynaud6 & Gaëlle Pierron6 & Marie-Christine Machet1,8 & Annabel Maruani7,8,9 Received: 15 May 2018 /Revised: 11 July 2018 /Accepted: 12 July 2018 /Published online: 6 September 2018 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Cutaneous spindle-cell neoplasms in adults as well as children represent a frequent dilemma for pathologists. Along this neoplasm spectrum, the differential diagnosis with CD34-positive proliferations can be challenging, particularly concerning neoplasms of fibrohistiocytic and fibroblastic lineages. In children, cutaneous and superficial soft-tissue neoplasms with CD34-positive spindle cells are associated with benign to intermediate malignancy potential and include lipofibromatosis, plaque-like CD34-positive dermal fibroma, fibroblastic connective tissue nevus, and congenital dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Molecular biology has been valuable in showing dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans and infantile fibrosarcoma that are characterized by COL1A1-PDGFB and ETV6-NTRK3 rearrangements respectively. We report a case of congenital CD34- positive dermohypodermal spindle-cell neoplasm occurring in a female infant and harboring a novel KHDRBS1-NTRK3 fusion. This tumor could belong to a new subgroup of pediatric cutaneous spindle-cell neoplasms, be an atypical presentation of a plaque-like CD34-positive dermal fibroma, of a fibroblastic connective tissue nevus, or represent a dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans with an alternative gene rearrangement. Keywords Cutaneous . Neoplasms . Spindle-cell Introduction Cutaneous spindle-cell proliferations form a large spectrum of * Annabel Maruani neoplasms occurring in children and adults. -

Morphological and Immunohistochemical Characteristics of Surgically Removed Paediatric Renal Tumours in Latvia (1997–2010)

DOI: 10.2478/v10163-012-0008-6 ACTA CHIRURGICA LATVIENSIS • 2011 (11) ORIGINAL ARTICLE Morphological and Immunohistochemical Characteristics of Surgically Removed Paediatric Renal Tumours in Latvia (1997–2010) Ivanda Franckeviča*,**, Regīna Kleina*, Ivars Melderis** *Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia **Children’s Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia Summary Introduction. Paediatric renal tumours represent 7% of all childhood malignancies. The variable appearances of the tumours and their rarity make them especially challenging group of lesions for the paediatric pathologist. In Latvia diagnostics and treatment of childhood malignancies is concentrated in Children’s Clinical University Hospital. Microscopic evaluation of them is realised in Pathology office of this hospital. Aim of the study is to analyze morphologic spectrum of children kidney tumours in Latvia and to characterise them from modern positions with wide range of immunohistochemical markers using morphological material of Pathology bureau of Children’s Clinical University Hospital. Materials and methods. We have analyzed surgically removed primary renal tumours in Children Clinical University Hospital from the year 1997 till 2010. Samples were fixed in 10% formalin fluid, imbedded in paraffin and haematoxylin-eosin stained slides were re-examined. Immunohistochemical re-investigation was made in 65.91% of cases. For differential diagnostic purposes were used antibodies for the detection of bcl-2, CD34, EMA, actin, desmin, vimentin, CKAE1/AE3, CK7, Ki67, LCA, WT1, CD99, NSE, chromogranin, synaptophyzin, S100, myoglobin, miogenin, MyoD1 (DakoCytomation) and INI1 protein (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Results. During the revised period there were diagnosed 44 renal tumours. Accordingly of morphological examination data neoplasms were divided: 1) nephroblastoma – 75%, 2) clear cell sarcoma – 2.27%, 3) rhabdoid tumour – 4.55%, 4) angiomyolipoma – 4.55%, 5) embrional rhabdomyosarcoma – 2.27%, 6) mesoblastic nephroma – 4.55%, 7) multicystic nephroma – 4.55%, 8) angiosarcoma – 2.27%. -

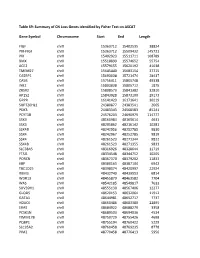

Table S9: Summary of CN Loss Genes Identified by Fisher Test on ASCAT

Table S9: Summary of CN Loss Genes identified by Fisher Test on ASCAT Gene Symbol Chromosome Start End Length FIGF chrX 15363712 15402535 38824 PIR-FIGF chrX 15363712 15509432 145721 PIR chrX 15402923 15511711 108789 BMX chrX 15518899 15574652 55754 ACE2 chrX 15579155 15620192 41038 TMEM27 chrX 15645440 15683154 37715 CA5BP1 chrX 15693038 15721474 28437 CA5B chrX 15756411 15805748 49338 INE2 chrX 15803838 15805712 1875 ZRSR2 chrX 15808573 15841382 32810 AP1S2 chrX 15843928 15873100 29173 GRPR chrX 16141423 16171641 30219 SUPT20HL1 chrX 24380877 24383541 2665 PDK3 chrX 24483343 24568583 85241 PCYT1B chrX 24576203 24690979 114777 SSX9 chrX 48160984 48165614 4631 SSX3 chrX 48205862 48216142 10281 SSX4B chrX 48242956 48252785 9830 SSX4 chrX 48242967 48252785 9819 SSX4 chrX 48261523 48271344 9822 SSX4B chrX 48261523 48271355 9833 SLC38A5 chrX 48316926 48328644 11719 FTSJ1 chrX 48334548 48344752 10205 PORCN chrX 48367370 48379202 11833 EBP chrX 48380163 48387104 6942 TBC1D25 chrX 48398074 48420997 22924 RBM3 chrX 48432740 48439553 6814 WDR13 chrX 48455879 48463582 7704 WAS chrX 48542185 48549817 7633 SUV39H1 chrX 48555130 48567406 12277 GLOD5 chrX 48620153 48632064 11912 GATA1 chrX 48644981 48652717 7737 HDAC6 chrX 48660486 48683380 22895 ERAS chrX 48684922 48688279 3358 PCSK1N chrX 48689503 48694036 4534 TIMM17B chrX 48750729 48755426 4698 PQBP1 chrX 48755194 48760422 5229 SLC35A2 chrX 48760458 48769235 8778 PIM2 chrX 48770458 48776413 5956 OTUD5 chrX 48779302 48815648 36347 KCND1 chrX 48818638 48828251 9614 GRIPAP1 chrX 48830133 48858675 28543 -

Pediatric Abdominal Masses

Pediatric Abdominal Masses Andrew Phelps MD Assistant Professor of Pediatric Radiology UCSF Benioff Children's Hospital No Disclosures Take Home Message All you need to remember are the 5 common masses that shouldn’t go to pathology: 1. Infection 2. Adrenal hemorrhage 3. Renal angiomyolipoma 4. Ovarian torsion 5. Liver hemangioma Keys to (Differential) Diagnosis 1. Location? 2. Age? 3. Cystic? OUTLINE 1. Kidney 2. Adrenal 3. Pelvis 4. Liver OUTLINE 1. Kidney 2. Adrenal 3. Pelvis 4. Liver Renal Tumor Mimic – Any Age Infection (Pyelonephritis) Don’t send to pathology! Renal Tumor Mimic – Any Age Abscess Don’t send to pathology! Peds Renal Tumors Infant: 1) mesoblastic nephroma 2) nephroblastomatosis 3) rhabdoid tumor Child: 1) Wilm's tumor 2) lymphoma 3) angiomyolipoma 4) clear cell sarcoma 5) multilocular cystic nephroma Teen: 1) renal cell carcinoma 2) renal medullary carcinoma Peds Renal Tumors Infant: 1) mesoblastic nephroma 2) nephroblastomatosis 3) rhabdoid tumor Child: 1) Wilm's tumor 2) lymphoma 3) angiomyolipoma 4) clear cell sarcoma 5) multilocular cystic nephroma Teen: 1) renal cell carcinoma 2) renal medullary carcinoma Renal Tumors - Infant 1) mesoblastic nephroma 2) nephroblastomatosis 3) rhabdoid tumor Renal Tumors - Infant 1) mesoblastic nephroma 2) nephroblastomatosis 3) rhabdoid tumor - Most common - Can’t distinguish from congenital Wilms. Renal Tumors - Infant 1) mesoblastic nephroma 2) nephroblastomatosis 3) rhabdoid tumor Look for Multiple biggest or diffuse and masses. ugliest. Renal Tumors - Infant 1) mesoblastic -

Congenital Mesoblastic Nephroma: Possible Prognostic and Management Value of Assessing J Clin Pathol: First Published As 10.1136/Jcp.44.4.317 on 1 April 1991

J Clin Pathol 1991;44:317-320 317 Congenital mesoblastic nephroma: Possible prognostic and management value of assessing J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.44.4.317 on 1 April 1991. Downloaded from DNA content J C Barrantes, C Toyn, K R Muir, S E Parkes, F Raafat, A H Cameron, H B Marsden, J R Mann Abstract appears benign with a leiomyomatous pattern The case records and pathology of all composed of interlacing bundles of spindle children with kidney tumours treated in cells and few mitotic figures; congenital the West Midlands Health Authority mesoblastic nephroma is densely cellular, with Region (WMHAR) from 1957 to 1986 many mitotic figures. Both patterns can be were reviewed. The histology was re- found in the same tumour, referred to as a viewed by a panel of three paediatric mixed tumour.9 pathologists. Thirteen (6%) out of 211 In trying to explain the histogenesis of these cases were considered to have congenital tumours, Snyder et al"' proposed a theory mesoblastic nephroma (CMN). Nine using the "two hit" model, described by were of the conventional type, three of Knudson." In this model congenital meso- the atypical cellular type, and one blastic nephroma would occur after a neoplas- mixed. DNA ploidy was investigated and tic mutation in the early stages of embryogen- showed two of the tumours to be aneu- esis, whereas atypical cellular mesoblastic ploid and nine diploid (tissue was not nephroma would develop in the later stages, available in the two other cases). The two but before the blastema has undergone meta- aneuploid tumours were of atypical nephric differentiation. -

Gene Expression Profiling Using Nanostring Digital RNA Counting to Identify Potential Target Antigens for Melanoma Immunotherapy

Published OnlineFirst September 10, 2013; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1253 Clinical Cancer Human Cancer Biology Research Gene Expression Profiling using Nanostring Digital RNA Counting to Identify Potential Target Antigens for Melanoma Immunotherapy Rachel E. Beard, Daniel Abate-Daga, Shannon F. Rosati, Zhili Zheng, John R. Wunderlich, Steven A. Rosenberg, and Richard A. Morgan Abstract Purpose: The success of immunotherapy for the treatment of metastatic cancer is contingent on the identification of appropriate target antigens. Potential targets must be expressed on tumors but show restricted expression on normal tissues. To maximize patient eligibility, ideal target antigens should be expressed on a high percentage of tumors within a histology and, potentially, in multiple different malignancies. Design: A Nanostring probeset was designed containing 97 genes, 72 of which are considered potential candidate genes for immunotherapy. Five established melanoma cell lines, 59 resected metastatic mela- noma tumors, and 31 normal tissue samples were profiled and analyzed using Nanostring technology. Results: Of the 72 potential target genes, 33 were overexpressed in more than 20% of studied melanoma tumor samples. Twenty of those genes were identified as differentially expressed between normal tissues and tumor samples by ANOVA analysis. Analysis of normal tissue gene expression identified seven genes with limited normal tissue expression that warrant further consideration as potential immunotherapy target antigens: CSAG2, MAGEA3, MAGEC2, IL13RA2, PRAME, CSPG4, and SOX10. These genes were highly overexpressed on a large percentage of the studied tumor samples, with expression in a limited number of normal tissue samples at much lower levels. Conclusion: The application of Nanostring RNA counting technology was used to directly quantitate the gene expression levels of multiple potential tumor antigens.