Regulation of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 2 (Mtorc2)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snapshot: Axon Guidance Pasterkamp R

494 1 Cell Cell ??? SnapShot: Axon Guidance 153 SnapShot: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX 1 2 , ??MONTH?? ??DATE??, 200? ©200? Elsevier Inc. 200?©200? ElsevierInc. , ??MONTH?? ??DATE??, DOI R. Jeroen Pasterkamp and Alex L. Kolodkin , April11, 2013©2013Elsevier Inc. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.031 AUTHOR XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX 1 AFFILIATIONDepartment of XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Neuroscience and Pharmacology, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, University Medical Center Utrecht, 3584 CG Utrecht, The Netherlands; 2Department of Neuroscience, HHMI, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21212, USA Axon attraction and repulsion Surround repulsion Selective fasciculation Topographic mapping Self-avoidance Wild-type Dscam1 mutant Sema3A A Retina SC/Tectum EphB EphrinB P D D Mutant T A neuron N P A V V Genomic DNA P EphA EphrinA Slit Exon 4 (12) Exon 6 (48) Exon 9 (33) Exon 17 (2) Netrin Commissural axon guidance Surround repulsion of peripheral Grasshopper CNS axon Retinotectal mapping at the CNS midline nerves in vertebrates fasciculation in vertebrates Drosophila mushroom body XXXXXXXXX NEURITE/CELL Isoneuronal Sema3 Slit Sema1/4-6 Heteroneuronal EphrinA EphrinB FasII Eph Genomic DNA Pcdh-α (14) Pcdh-β (22) Pcdh-γ (22) Variable Con Variable Con Nrp Plexin ** *** Netrin LAMELLIPODIA Con DSCAM ephexin Starburst amacrine cells in mammalian retina Ras-GTP Vav See online version for legend and references. α-chimaerin GEFs/GAPs Robo FARP Ras-GDP LARG RhoGEF Kinases DCC cc0 GTPases PKA cc1 FAK Regulatory Mechanisms See online versionfor??????. Cdc42 GSK3 cc2 Rac PI3K P1 Rho P2 cc3 Abl Proteolytic cleavage P3 Regulation of expression (TF, miRNA, FILOPODIA srGAP Cytoskeleton regulatory proteins multiple isoforms) Sos Trio Pcdh Cis inhibition DOCK180 PAK ROCK Modulation of receptors’ output LIMK Myosin-II Colin Forward and reverse signaling Actin Trafcking and endocytosis NEURONAL GROWTH CONE Microtubules SnapShot: Axon Guidance R. -

Lymphocyte/WBC-Based Comprehensive Testing Via Next-Gen Sequencing NF1/SPRED1 and Other Rasopathy Related Conditions on Blood/Saliva

Last Updated October 2019 Institutional Price TAT Genetic Test CPT Codes Z codes Specimen Requirements (USD$) (working days) Lymphocyte/WBC-based Comprehensive Testing via Next-Gen Sequencing NF1/SPRED1 and Other RASopathy Related Conditions on Blood/Saliva NF1- only NGS testing and copy number analysis for the NF1 gene (NF1-NG) This testing includes an average coverage of >1600x to allow for the identification of (1) 3-6ml whole blood in EDTA (purple topped) tubes mosaicism as low as 3-5% of the alleles. In addition, novel variants identified in the $1,000 81408 25 (2) Oragene 575 saliva kit (provided by the MGL) ZB6A9 NF1 gene will be confirmed via RNA-based analysis at no additional charge. RNA- $1,600 (RUSH) 81479 15 (RUSH) (3) DNA sample (25ul volume at 3ug, O.D. value at based testing will also be provided to non-founder, multigenerational families with 260:280 ≥1.8) “classic” NF1 at no additional charge if next-generation sequencing is found negative. (1) 3-6ml whole blood in EDTA (purple topped) tubes SPRED1-only NGS testing and copy number analysis for SPRED1 (SPD1-NG) $800 81405 25 (2) Oragene 575 saliva kit (provided by the MGL) This testing includes an average coverage of >1600x to allow for the identification of ZB6AC $1,400 (RUSH) 81479 15 (RUSH) (3) DNA sample (25ul volume at 3ug, O.D. value at mosaicism as low as 3-5% of the alleles after comprehensive NF1 analysis. 260:280 ≥1.8) NF1/SPRED1 NGS testing and copy number analysis for NF1 and SPRED1 (NFSP-NG) (1) 3-6ml whole blood in EDTA (purple topped) tubes 81408 This testing includes an average coverage of >1600x to allow for the identification of $1,100 25 (2) Oragene 575 saliva kit (provided by the MGL) 81405 ZB6A8 mosaicism as low as 3-5% of the alleles. -

The Atypical Guanine-Nucleotide Exchange Factor, Dock7, Negatively Regulates Schwann Cell Differentiation and Myelination

The Journal of Neuroscience, August 31, 2011 • 31(35):12579–12592 • 12579 Cellular/Molecular The Atypical Guanine-Nucleotide Exchange Factor, Dock7, Negatively Regulates Schwann Cell Differentiation and Myelination Junji Yamauchi,1,3,5 Yuki Miyamoto,1 Hajime Hamasaki,1,3 Atsushi Sanbe,1 Shinji Kusakawa,1 Akane Nakamura,2 Hideki Tsumura,2 Masahiro Maeda,4 Noriko Nemoto,6 Katsumasa Kawahara,5 Tomohiro Torii,1 and Akito Tanoue1 1Department of Pharmacology and 2Laboratory Animal Resource Facility, National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Setagaya, Tokyo 157-8535, Japan, 3Department of Biological Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Midori, Yokohama 226-8501, Japan, 4IBL, Ltd., Fujioka, Gumma 375-0005, Japan, and 5Department of Physiology and 6Bioimaging Research Center, Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0374, Japan In development of the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells proliferate, migrate, and ultimately differentiate to form myelin sheath. In all of the myelination stages, Schwann cells continuously undergo morphological changes; however, little is known about their underlying molecular mechanisms. We previously cloned the dock7 gene encoding the atypical Rho family guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) and reported the positive role of Dock7, the target Rho GTPases Rac/Cdc42, and the downstream c-Jun N-terminal kinase in Schwann cell migration (Yamauchi et al., 2008). We investigated the role of Dock7 in Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. Knockdown of Dock7 by the specific small interfering (si)RNA in primary Schwann cells promotes dibutyryl cAMP-induced morpholog- ical differentiation, indicating the negative role of Dock7 in Schwann cell differentiation. It also results in a shorter duration of activation of Rac/Cdc42 and JNK, which is the negative regulator of myelination, and the earlier activation of Rho and Rho-kinase, which is the positive regulator of myelination. -

TSC1/TSC2 Signaling in the CNS ⇑ Juliette M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector FEBS Letters 585 (2011) 973–980 journal homepage: www.FEBSLetters.org Review TSC1/TSC2 signaling in the CNS ⇑ Juliette M. Han, Mustafa Sahin The F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center, Department of Neurology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA article info abstract Article history: Over the past several years, the study of a hereditary tumor syndrome, tuberous sclerosis complex Received 5 January 2011 (TSC), has shed light on the regulation of cellular proliferation and growth. TSC is an autosomal Revised 1 February 2011 dominant disorder that is due to inactivating mutations in TSC1 or TSC2 and characterized by benign Accepted 1 February 2011 tumors (hamartomas) involving multiple organ systems. The TSC1/2 complex has been found to play Available online 15 February 2011 a crucial role in an evolutionarily-conserved signaling pathway that regulates cell growth: the Edited by Wilhelm Just mTORC1 pathway. This pathway promotes anabolic processes and inhibits catabolic processes in response to extracellular and intracellular factors. Findings in cancer biology have reinforced the critical role for TSC1/2 in cell growth and proliferation. In contrast to cancer cells, in the CNS, the Keywords: mTOR TSC1/2 complex not only regulates cell growth/proliferation, but also orchestrates an intricate and Autism finely tuned system that has distinctive roles under different conditions, depending on cell type, Translation stage of development, and subcellular localization. Overall, TSC1/2 signaling in the CNS, via its multi-faceted roles, contributes to proper neural connectivity. -

Mtor: a Pharmacologic Target for Autophagy Regulation

mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation Young Chul Kim, Kun-Liang Guan J Clin Invest. 2015;125(1):25-32. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI73939. Review mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase, is a master regulator of cellular metabolism. mTOR regulates cell growth and proliferation in response to a wide range of cues, and its signaling pathway is deregulated in many human diseases. mTOR also plays a crucial role in regulating autophagy. This Review provides an overview of the mTOR signaling pathway, the mechanisms of mTOR in autophagy regulation, and the clinical implications of mTOR inhibitors in disease treatment. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/73939/pdf The Journal of Clinical Investigation REVIEW SERIES: AUTOPHAGY Series Editor: Guido Kroemer mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation Young Chul Kim and Kun-Liang Guan Department of Pharmacology and Moores Cancer Center, UCSD, La Jolla, California, USA. mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase, is a master regulator of cellular metabolism. mTOR regulates cell growth and proliferation in response to a wide range of cues, and its signaling pathway is deregulated in many human diseases. mTOR also plays a crucial role in regulating autophagy. This Review provides an overview of the mTOR signaling pathway, the mechanisms of mTOR in autophagy regulation, and the clinical implications of mTOR inhibitors in disease treatment. Overview of mTOR signaling pathway such as insulin and IGF activate their cognate receptors (recep- Nutrients, growth factors, and cellular energy levels are key deter- tor tyrosine kinases [RTKs]) and subsequently activate the PI3K/ minants of cell growth and proliferation. mTOR, a serine/threon- AKT signaling axis. -

Mutational Spectrum of the TSC1 Gene in a Cohort of 225 Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Patients: J Med Genet: First Published As 10.1136/Jmg.36.4.285 on 1 April 1999

J Med Genet 1999;36:285–289 285 Mutational spectrum of the TSC1 gene in a cohort of 225 tuberous sclerosis complex patients: J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.36.4.285 on 1 April 1999. Downloaded from no evidence for genotype-phenotype correlation Marjon van Slegtenhorst, Senno Verhoef, Anita Tempelaars, Lida Bakker, Qi Wang, Marja Wessels, Remco Bakker, Mark Nellist, Dick Lindhout, Dicky Halley, Ans van den Ouweland Abstract TSC1 locus on chromosome 9q34 and the Tuberous sclerosis complex is an inherited other half to the TSC2 locus on chromosome tumour suppressor syndrome, caused by a 16p13.67 The TSC1 and TSC2 genes were mutation in either the TSC1 or TSC2 identified by positional cloning89 and there is gene. The disease is characterised by a abundant evidence that both genes act as broad phenotypic spectrum that can in- tumour suppressor genes.10–13 clude seizures, mental retardation, renal The TSC2 gene consists of 41 exons, dysfunction, and dermatological abnor- spanning 43 kb of genomic DNA.14 It encodes malities. The TSC1 gene was recently a 200 kDa protein, tuberin, which has a identified and has 23 exons, spanning 45 putative GAP activity for rab515 and rap1,16 two kb of genomic DNA, and encoding an 8.6 members of the ras superfamily of small kb mRNA. After screening all 21 coding GTPases. The mutational spectrum of TSC2 exons in our collection of 225 unrelated includes a number of large deletions often dis- 17 18 patients, only 29 small mutations were rupting the PKD1 gene as well, but also 19–27 detected, suggesting that TSC1 mutations point mutations and a number of missense 28 are under-represented among TSC pa- changes. -

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association Between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic

Supplementary Material DNA Methylation in Inflammatory Pathways Modifies the Association between BMI and Adult-Onset Non- Atopic Asthma Ayoung Jeong 1,2, Medea Imboden 1,2, Akram Ghantous 3, Alexei Novoloaca 3, Anne-Elie Carsin 4,5,6, Manolis Kogevinas 4,5,6, Christian Schindler 1,2, Gianfranco Lovison 7, Zdenko Herceg 3, Cyrille Cuenin 3, Roel Vermeulen 8, Deborah Jarvis 9, André F. S. Amaral 9, Florian Kronenberg 10, Paolo Vineis 11,12 and Nicole Probst-Hensch 1,2,* 1 Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, 4051 Basel, Switzerland; [email protected] (A.J.); [email protected] (M.I.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 Department of Public Health, University of Basel, 4001 Basel, Switzerland 3 International Agency for Research on Cancer, 69372 Lyon, France; [email protected] (A.G.); [email protected] (A.N.); [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (C.C.) 4 ISGlobal, Barcelona Institute for Global Health, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (A.-E.C.); [email protected] (M.K.) 5 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain 6 CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), 08005 Barcelona, Spain 7 Department of Economics, Business and Statistics, University of Palermo, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 8 Environmental Epidemiology Division, Utrecht University, Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences, 3584CM Utrecht, Netherlands; [email protected] 9 Population Health and Occupational Disease, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, SW3 6LR London, UK; [email protected] (D.J.); [email protected] (A.F.S.A.) 10 Division of Genetic Epidemiology, Medical University of Innsbruck, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria; [email protected] 11 MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, W2 1PG London, UK; [email protected] 12 Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine (IIGM), 10126 Turin, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-61-284-8378 Int. -

Whole Exome Sequencing in Families at High Risk for Hodgkin Lymphoma: Identification of a Predisposing Mutation in the KDR Gene

Hodgkin Lymphoma SUPPLEMENTARY APPENDIX Whole exome sequencing in families at high risk for Hodgkin lymphoma: identification of a predisposing mutation in the KDR gene Melissa Rotunno, 1 Mary L. McMaster, 1 Joseph Boland, 2 Sara Bass, 2 Xijun Zhang, 2 Laurie Burdett, 2 Belynda Hicks, 2 Sarangan Ravichandran, 3 Brian T. Luke, 3 Meredith Yeager, 2 Laura Fontaine, 4 Paula L. Hyland, 1 Alisa M. Goldstein, 1 NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group, NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Stephen J. Chanock, 5 Neil E. Caporaso, 1 Margaret A. Tucker, 6 and Lynn R. Goldin 1 1Genetic Epidemiology Branch, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 2Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; 3Ad - vanced Biomedical Computing Center, Leidos Biomedical Research Inc.; Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, Frederick, MD; 4Westat, Inc., Rockville MD; 5Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD; and 6Human Genetics Program, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA ©2016 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper. doi:10.3324/haematol.2015.135475 Received: August 19, 2015. Accepted: January 7, 2016. Pre-published: June 13, 2016. Correspondence: [email protected] Supplemental Author Information: NCI DCEG Cancer Sequencing Working Group: Mark H. Greene, Allan Hildesheim, Nan Hu, Maria Theresa Landi, Jennifer Loud, Phuong Mai, Lisa Mirabello, Lindsay Morton, Dilys Parry, Anand Pathak, Douglas R. Stewart, Philip R. Taylor, Geoffrey S. Tobias, Xiaohong R. Yang, Guoqin Yu NCI DCEG Cancer Genomics Research Laboratory: Salma Chowdhury, Michael Cullen, Casey Dagnall, Herbert Higson, Amy A. -

Immersion Course Lecture Kelly

Genomic Counseling in the research setting Kelly East, MS CGC Genetic Counselor HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology single gene disorders • mutation in a single gene leads to disease • often has characteristic family inheritance patterns J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73:ii5-ii11 Genes that code for hemoglobin 1 2 3 4 5 HBB 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 HBA2 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 X Y http://www.genome.gov/glossary/resources/karyotype.pdf TARDBP Genes associated ALS2 with ALS 1 2 3 4 5 C9ORF72 OPTN FIG4 ATXN2 SETX 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 ANG SPG11 FUS 13 14 15 16 17 18 VAPB UBQLN2 SOD1 19 20 21 22 X Y http://www.genome.gov/glossary/resources/karyotype.pdf complex traits • most common traits and diseases have a complex etiology • causative risks can include genetic changes (both large and small scale) environmental factors (head injury, nutrition, exposure to toxins) societal factors (death of family member, abuse, hardships) • in most cases - not triggered by a change in a single gene but rather by the interaction of several genetic, environmental and societal risks spectrum of human genetic conditions CGTATACCGGGTCATGCACGTGTAGAGCGAGTTAGCTCGCTGGCTAAAGAGGGTCGAC ATCCGCGAGTTTATGAGGAAGAATCGGCAGCTTGACCGAAGAGGCGTGGTAAGACCCG TTAGGGATCGTATACCGGGTCATGCACGTGTAGAGCGAGTTAGCTCGCTGGCTAAAGA GGGTCGACATCCGCGAGTTTATGAGGAAGAATCGGCAGCTTGACCGAAGAGGCGTGGT AAGACCCGTTAGGGATCGTATACCGGGTCATGCACGTGTAGAGCGAGTTAGCTCGCTG GCTAAAGAGGGTCGACATCCGCGAGTTTATGAGGAAGAATCGGCAGCTTGACCGAAGA GGCGTGGTAAGACCCGTTAGGGATCGTATACCGGGTCATGCACGTGTAGAGCGAGTTA in patients with a suspected genetic -

Tuberous Sclerosis Complex: Molecular Pathogenesis and Animal Models

Neurosurg Focus 20 (1):E4, 2006 Tuberous sclerosis complex: molecular pathogenesis and animal models LEANDRO R. PIEDIMONTE, M.D., IAN K. WAILES, M.D., AND HOWARD L. WEINER, M.D. Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery, New York University School of Medicine, New York, New York Mutations in one of two genes, TSC1 and TSC2, result in a similar disease phenotype by disrupting the normal inter- action of their protein products, hamartin and tuberin, which form a functional signaling complex. Disruption of these genes in the brain results in abnormal cellular differentiation, migration, and proliferation, giving rise to the charac- teristic brain lesions of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) called cortical tubers. The most devastating complications of TSC affect the central nervous system and include epilepsy, mental retardation, autism, and glial tumors. Relevant animal models, including conventional and conditional knockout mice, are valuable tools for studying the normal func- tions of tuberin and hamartin and the way in which disruption of their expression gives rise to the variety of clinical features that characterize TSC. In the future, these animals will be invaluable preclinical models for the development of highly specific and efficacious treatments for children affected with TSC. KEY WORDS • tuberous sclerosis • pathogenesis • animal model Tuberous sclerosis complex is an autosomal-dominant zures, mental retardation, and autism.1,51 The number and tumor predisposition syndrome that affects approximately location of cortical tubers and the patient’s age at seizure 1 in 7500 individuals worldwide.19 The TSC is character- onset are highly correlated with neurological outcomes.1,30 ized by benign hamartomatous growths in multiple organs, Epilepsy occurs in approximately 80% of affected indi- including the kidney, skin, retina, lung, and brain. -

Identification of Two Signaling Submodules Within the Crkii/ELMO

Cell Death and Differentiation (2007) 14, 963–972 & 2007 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1350-9047/07 $30.00 www.nature.com/cdd Identification of two signaling submodules within the CrkII/ELMO/Dock180 pathway regulating engulfment of apoptotic cells A-C Tosello-Trampont1,4, JM Kinchen1,2,4, E Brugnera1,3, LB Haney1, MO Hengartner2 and KS Ravichandran*,1 Removal of apoptotic cells is a dynamic process coordinated by ligands on apoptotic cells, and receptors and other signaling proteins on the phagocyte. One of the fundamental challenges is to understand how different phagocyte proteins form specific and functional complexes to orchestrate the recognition/removal of apoptotic cells. One evolutionarily conserved pathway involves the proteins cell death abnormal (CED)-2/chicken tumor virus no. 10 (CT10) regulator of kinase (Crk)II, CED-5/180 kDa protein downstream of chicken tumor virus no. 10 (Crk) (Dock180), CED-12/engulfment and migration (ELMO) and MIG-2/RhoG, leading to activation of the small GTPase CED-10/Rac and cytoskeletal remodeling to promote corpse uptake. Although the role of ELMO : Dock180 in regulating Rac activation has been well defined, the function of CED-2/CrkII in this complex is less well understood. Here, using functional studies in cell lines, we observe that a direct interaction between CrkII and Dock180 is not required for efficient removal of apoptotic cells. Similarly, mutants of CED-5 lacking the CED-2 interaction motifs could rescue engulfment and migration defects in CED-5 deficient worms. Mutants of CrkII and Dock180 that could not biochemically interact could colocalize in membrane ruffles. -

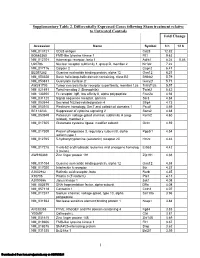

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially Expressed Genes following Sham treatment relative to Untreated Controls Fold Change Accession Name Symbol 3 h 12 h NM_013121 CD28 antigen Cd28 12.82 BG665360 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 Flt1 9.63 NM_012701 Adrenergic receptor, beta 1 Adrb1 8.24 0.46 U20796 Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 Nr1d2 7.22 NM_017116 Calpain 2 Capn2 6.41 BE097282 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 6.21 NM_053328 Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 Bhlhb2 5.79 NM_053831 Guanylate cyclase 2f Gucy2f 5.71 AW251703 Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a Tnfrsf12a 5.57 NM_021691 Twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) Twist2 5.42 NM_133550 Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide Fcer2a 4.93 NM_031120 Signal sequence receptor, gamma Ssr3 4.84 NM_053544 Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 Sfrp4 4.73 NM_053910 Pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled/coil domains 1 Pscd1 4.69 BE113233 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 Socs2 4.68 NM_053949 Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag- Kcnh2 4.60 related), member 2 NM_017305 Glutamate cysteine ligase, modifier subunit Gclm 4.59 NM_017309 Protein phospatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha Ppp3r1 4.54 isoform,type 1 NM_012765 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C Htr2c 4.46 NM_017218 V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog Erbb3 4.42 3 (avian) AW918369 Zinc finger protein 191 Zfp191 4.38 NM_031034 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 4.38 NM_017020 Interleukin 6 receptor Il6r 4.37 AJ002942