Evidentiality and the Expression of Speaker's Stance in Romance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

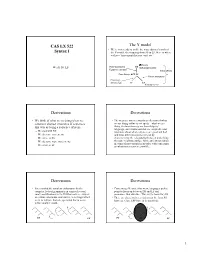

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Minimal Pronouns1

1 Minimal Pronouns1 Fake Indexicals as Windows into the Properties of Bound Variable Pronouns Angelika Kratzer University of Massachusetts at Amherst June 2006 Abstract The paper challenges the widely accepted belief that the relation between a bound variable pronoun and its antecedent is not necessarily submitted to locality constraints. It argues that the locality constraints for bound variable pronouns that are not explicitly marked as such are often hard to detect because of (a) alternative strategies that produce the illusion of true bound variable interpretations and (b) language specific spell-out noise that obscures the presence of agreement chains. To identify and control for those interfering factors, the paper focuses on ‘fake indexicals’, 1st or 2nd person pronouns with bound variable interpretations. Following up on Kratzer (1998), I argue that (non-logophoric) fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features and acquire the remaining features via chains of local agreement relations established in the syntax. If fake indexicals are born with an incomplete set of features, we need a principled account of what those features are. The paper derives such an account from a semantic theory of pronominal features that is in line with contemporary typological work on possible pronominal paradigms. Keywords: agreement, bound variable pronouns, fake indexicals, meaning of pronominal features, pronominal ambiguity, typologogy of pronouns. 1 . I received much appreciated feedback from audiences in Paris (CSSP, September 2005), at UC Santa Cruz (November 2005), the University of Saarbrücken (workshop on DPs and QPs, December 2005), the University of Tokyo (SALT XIII, March 2006), and the University of Tromsø (workshop on decomposition, May 2006). -

Children's Comprehension of the Verbal Aspect in Serbian

PSIHOLOGIJA, 2021, Online First, UDC © 2021 by authors DOI https://doi.org/10.2298/PSI191120003S Children’s Comprehension of the Verbal Aspect in Serbian * Maja Savić1,3, Maša Popović2,3, and Darinka Anđelković2,3 1Faculty of Philology, University of Belgrade, Serbia 2Institute of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Serbia 3Laboratory of Experimental Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade, Serbia The aim of the study was to investigate how Serbian native speaking preschool children comprehend perfective and imperfective aspect in comparison to adults. After watching animated movies with complete, incomplete and unstarted actions, the participants were asked questions with a perfective or imperfective verb form and responded by pointing to the event(s) that corresponded to each question. The results converged to a clear developmental trend in understanding of aspectual forms. The data indicate that the acquisition of perfective precedes the acquisition of imperfective: 3-year-olds typically understand only the meaning of perfective; most 5-year-olds have almost adult-like understanding of both aspectual forms, while 4-year-olds are a transitional group. Our results support the viewpoint that children's and adults’ representations of this language category differ qualitatively, and we argue that mastering of aspect semantics is a long-term process that presupposes a certain level of cognitive and pragmatic development, and lasts throughout the preschool period. Keywords: verbal aspect, language development, comprehension, Serbian language Highlights: ● The first experimental study on verbal aspect comprehension in Serbian. ● Crucial changes in aspect comprehension happen between ages 3 and 5. Corresponding author: [email protected] Note. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia, grant number ON179033. -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

Binding Theory

HG4041 Theories of Grammar Binding Theory Francis Bond Division of Linguistics and Multilingual Studies http://www3.ntu.edu.sg/home/fcbond/ [email protected] Lecture 5 Location: HSS SR3 HG4041 (2013) Overview ➣ What we are trying to do ➣ Last week: Semantics ➣ Review of Chapter 1’s informal binding theory ➣ What we already have that’s useful ➣ What we add in Ch 7 (ARG-ST, ARP) ➣ Formalized Binding Theory ➣ Binding and PPs ➣ Imperatives Sag, Wasow and Bender (2003) — Chapter 7 1 What We’re Trying To Do ➣ Objectives ➢ Develop a theory of knowledge of language ➢ Represent linguistic information explicitly enough to distinguish well- formed from ill-formed expressions ➢ Be parsimonious, capturing linguistically significant generalizations. ➣ Why Formalize? ➢ To formulate testable predictions ➢ To check for consistency ➢ To make it possible to get a computer to do it for us Binding Theory 2 How We Construct Sentences ➣ The Components of Our Grammar ➢ Grammar rules ➢ Lexical entries ➢ Principles ➢ Type hierarchy (very preliminary, so far) ➢ Initial symbol (S, for now) ➣ We combine constraints from these components. ➣ More in hpsg.stanford.edu/book/slides/Ch6a.pdf, hpsg.stanford.edu/book/slides/Ch6b.pdf Binding Theory 3 Review of Semantics Binding Theory 4 Overview ➣ Which aspects of semantics we’ll tackle ➣ Semantics Principles ➣ Building semantics of phrases ➣ Modification, coordination ➣ Structural ambiguity Binding Theory 5 Our Slice of a World of Meanings Aspects of meaning we won’t account for (in this course) ➣ Pragmatics ➣ Fine-grained lexical semantics The meaning of life is ➢ life or life′ or RELN life "INST i # ➢ Not like wordnet: life1 ⊂ being1 ⊂ state1 . ➣ Quantification (covered lightly in the book) ➣ Tense, Mood, Aspect (covered in the book) Binding Theory 6 Our Slice of a World of Meanings MODE prop INDEX s RELN save RELN name RELN name SIT s RESTR , NAME Chris , NAME Pat * SAVER i + NAMED i NAMED j SAVED j “. -

Demonstrative Pronouns, Binding Theory, and Identity

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 7 Issue 1 Proceedings of the 24th Annual Penn Article 22 Linguistics Colloquium 2000 Demonstrative Pronouns, Binding Theory, and Identity Ivy Sichel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Sichel, Ivy (2000) "Demonstrative Pronouns, Binding Theory, and Identity," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 7 : Iss. 1 , Article 22. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss1/22 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss1/22 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Demonstrative Pronouns, Binding Theory, and Identity This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol7/iss1/22 Demonstrative Pronouns, Binding Theory, and Identity' Ivy Sichel 1 Introduction Standard Binding Theory assigns distinct binding conditions to three classes of nominal expressions, anaphors, pronominals. and R-expressions. implying that BT-relevant categories are sufficiently defined and unproblematically recognized by language users. Pronominals. for example. are understood as nominal expressions whose content is exhausted by grammatical fealUres. This paper compares two Hebrew pronominal classes. personal pronouns and demonstrative-pronouns (henceforth d-pronouns). given in (I) and (2): (I) a. hu avad b. hi avda H-rn.s worked-3.m.s H-f.s worked-3.f.s He I it worked She I it worked (2) a. ha-hu avad b. ha-hiavda the-H-m.s worked-3.m.s the-H-f.s worked-3.f.s That one worked That one worked c. -

Affirmative and Negated Modality*

Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis lingüístics. Vol. XIV (2009) 169-192 AFFIRMATIVE AND NEGATED MODALITY* Günter Radden Hamburg 0. INTR O DUCTI O N 0.1. Stating the problem Descriptions of modality in English often give the impression that the behaviour of modal verbs is erratic when they occur with negation. A particularly intriguing case is the behaviour of the modal verb must under negation. In its deontic sense, must is used both in affirmative and negated sentences, expressing obligation (1a) and prohibition (1b), respectively. In its epistemic sense, however, must is only used in affirmative sentences expressing necessity (2a). The modal verb that expresses the corresponding negated epistemic modality, i.e. impossibility, is can’t (2b). (1) a. You must switch off your mobile phone. [obligation] b. You mustn’t switch off your mobile phone. [prohibition] (2) a. Your mobile phone must be switched off. [necessity] b. Your mobile phone can’t be switched off. [impossibility] Explanations that have been offered for the use of epistemic can’t are not very helpful. Palmer (1990: 61) argues that mustn’t is not used for the negation of epistemic necessity because can’t is supplied, and Coates (1983: 20) suggests that can’t is used because mustn’t is unavailable. Both “explanations” beg the question: why should can’t be used to denote negated necessity and why should mustn’t be unavailable? Such questions have apparently not been asked for two interrelated reasons: first, the study of modality and negation has been dominated by logic and, secondly, since the modal verbs apparently do * An earlier version of this paper was published in Władysław Chłopicki, Andrzej Pawelec, and Agnieszka Pokojska (eds.), 2007, Cognition in Language: Volume in Honour of Professor Elżbieta Tabakowska, 224-254. -

The Japanese Sentence-Final Particle No and Mirativity* Keita Ikarashi

79 The Japanese Sentence-Final Particle No and Mirativity* Keita Ikarashi 1. Introduction Some languages develop grammatical items concerning a semantic category “whose primary meaning is speaker’s unprepared mind, unexpected new information, and concomitant surprise” (Aikhenvald (2004:209)). This category is generally called mirativity (cf. DeLancey (1997)). For example, in Magar, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Nepal, mirativity is expressed by “the verb stem plus nominaliser o, followed by le, [i.e.] a grammaticalised copula, functioning as an auxiliary and marker of imperfective aspect: �-oΣ le [STEM-NOM IMPF]” (Grunow-Hårsta (2007: 175)). Let us compare the following sentences:1 (1) a. thapa i-laŋ le Thapa P.Dem-Loc Cop ‘Thapa is here’ (non-mirative) b. thapa i-laŋ le-o le Thapa P.Dem-Loc Cop-Nom Impf (I realize to my surprise that) ‘Thapa is here’ (Grunow-Hårsta (2007:175)) According to Grunow-Hårsta (2007:175), the non-mirative sentence in (1a) “simply conveys information, making no claims as to its novelty or the speaker’s psychological reaction to it”; on the other hand, the mirative sentence in (1b), as the English translation shows, “conveys that the information is new and unexpected and is as much about this surprising newness as it is about the information itself.” In other words, this information has not been integrated into the speaker’s knowledge, and hence, it is evaluated as unexpected. Mirativity has gradually attracted attention since the seminal work of DeLancey (1997) and various mirative items have been detected in a number of languages. Unfortunately, however, there are very few studies which systematically and comprehensively investigate Japanese in terms of mirativity.2 * I wish to express my deepest gratitude to Masatoshi Honda, Teppei Otake, and Toshinao Nakazawa for helpful comments and suggestions.