Conflicts of Interest, Intra‐Group Financing and Procedural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Retrocomputing As Preservation and Remix

Retrocomputing as Preservation and Remix Yuri Takhteyev Quinn DuPont University of Toronto University of Toronto [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper looks at the world of retrocomputing, a constellation of largely non-professional practices involving old computing technology. Retrocomputing includes many activities that can be seen as constituting “preservation.” At the same time, it is often transformative, producing assemblages that “remix” fragments from the past with newer elements or joining together historic components that were never combined before. While such “remix” may seem to undermine preservation, it allows for fragments of computing history to be reintegrated into a living, ongoing practice, contributing to preservation in a broader sense. The seemingly unorganized nature of retrocomputing assemblages also provides space for alternative “situated knowledges” and histories of computing, which can sometimes be quite sophisticated. Recognizing such alternative epistemologies paves the way for alternative approaches to preservation. Keywords: retrocomputing, software preservation, remix Recovering #popsource In late March of 2012 Jordan Mechner received a shipment from his father, a box full of old floppies. Among them was a 3.5 inch disk labelled: “Prince of Persia / Source Code (Apple) / ©1989 Jordan Mechner (Original).” Mechner’s announcement of this find on his blog the next day took the world of nerds by storm.1 Prince of Persia, a game that Mechner single-handedly developed in the late 1980s, revolutionized computer games when it came out due to its surprisingly realistic representation of human movement. After being ported to DOS and Apple’s Mac OS in the early 1990s the game sold 2 million copies (Pham, 2001). -

A History of the Personal Computer Index/11

A History of the Personal Computer 6100 CPU. See Intersil Index 6501 and 6502 microprocessor. See MOS Legend: Chap.#/Page# of Chap. 6502 BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. Languages -- Numerals -- 7000 copier. See Xerox/Misc. 3 E-Z Pieces software, 13/20 8000 microprocessors. See 3-Plus-1 software. See Intel/Microprocessors Commodore 8010 “Star” Information 3Com Corporation, 12/15, System. See Xerox/Comp. 12/27, 16/17, 17/18, 17/20 8080 and 8086 BASIC. See 3M company, 17/5, 17/22 Microsoft/Prog. Languages 3P+S board. See Processor 8514/A standard, 20/6 Technology 9700 laser printing system. 4K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. See Xerox/Misc. Languages 16032 and 32032 micro/p. See 4th Dimension. See ACI National Semiconductor 8/16 magazine, 18/5 65802 and 65816 micro/p. See 8/16-Central, 18/5 Western Design Center 8K BASIC. See Microsoft/Prog. 68000 series of micro/p. See Languages Motorola 20SC hard drive. See Apple 80000 series of micro/p. See Computer/Accessories Intel/Microprocessors 64 computer. See Commodore 88000 micro/p. See Motorola 80 Microcomputing magazine, 18/4 --A-- 80-103A modem. See Hayes A Programming lang. See APL 86-DOS. See Seattle Computer A+ magazine, 18/5 128EX/2 computer. See Video A.P.P.L.E. (Apple Pugetsound Technology Program Library Exchange) 386i personal computer. See user group, 18/4, 19/17 Sun Microsystems Call-A.P.P.L.E. magazine, 432 microprocessor. See 18/4 Intel/Microprocessors A2-Central newsletter, 18/5 603/4 Electronic Multiplier. Abacus magazine, 18/8 See IBM/Computer (mainframe) ABC (Atanasoff-Berry 660 computer. -

History of Micro-Computers

M•I•C•R•O P•R•O•C•E•S•S•O•R E•V•O•L•U•T•I.O•N Reprinted by permission from BYTE, September 1985.. a McGraw-Hill Inc. publication. Prices quoted are in US S. EVOLUTION OF THE MICROPROCESSOR An informal history BY MARK GARETZ Author's note: The evolution of were many other applica- the microprocessor has followed tions for the new memory a complex and twisted path. To chip, which was signifi- those of you who were actually cantly larger than any that involved in some of the follow- had been produced ing history, 1 apologize if my before. version is not exactly like yours. About this time, the The opinions expressed in this summer of 1969, Intel was article are my own and may or approached by the may not represent reality as Japanese calculator manu- someone else perceives it. facturer Busicom to pro- duce a set of custom chips THE TRANSISTOR, devel- designed by Busicom oped at Bell Laboratories engineers for the Jap- in 1947, was designed to anese company's new line replace the vacuum tube, of calculators. The to switch electronic sig- calculators would have nals on and off. (Al- several chips, each of though, at the time, which would contain 3000 vacuum tubes were used to 5000 transistors. mainly as amplifiers, they Intel designer Marcian were also used as (led) Hoff was assigned to switches.) The advent of assist the team of Busi- the transistor made possi- com engineers that had ble a digital computer that taken up residence at didn't require an entire Intel. -

A History of the Amiga by Jeremy Reimer

A history of the Amiga By Jeremy Reimer 1 part 1: Genesis 3 part 2: The birth of Amiga 13 part 3: The first prototype 19 part 4: Enter Commodore 27 part 5: Postlaunch blues 39 part 6: Stopping the bleeding 48 part 7: Game on! 60 Shadow of the 16-bit Beast 71 2 A history of the Amiga, part 1: Genesis By Jeremy Reimer Prologue: the last day April 24, 1994 The flag was flying at half-mast when Dave Haynie drove up to the headquarters of Commodore International for what would be the last time. Dave had worked for Commodore at its West Chester, Pennsylvania, headquarters for eleven years as a hardware engineer. His job was to work on advanced products, like the revolutionary AAA chipset that would have again made the Amiga computer the fastest and most powerful multimedia machine available. But AAA, like most of the projects underway at Commodore, had been canceled in a series of cost-cutting measures, the most recent of which had reduced the staff of over one thousand people at the factory to less than thirty. "Bringing your camera on the last day, eh Dave?" the receptionist asked in a resigned voice."Yeah, well, they can't yell at me for spreading secrets any more, can they?" he replied. Dave took his camera on a tour of the factory, his low voice echoing through the empty hallways. "I just thought about it this morning," he said, referring to his idea to film the last moments of the company for which he had given so much of his life. -

Export Development Canada (EDC)

Reaching For Our Export Potential 2014 Annual Report 2014 Highlights 7,432 EDC served 7,432 customers in 201 countries 91% 6,088 91% of all our financing Helped 6,088 SMEs conduct transactions done in $13.6 billion in exports partnership with financial institutions 82% $28.9B 1,802 82% of our customers Our customers’ business in Canadian exporters were SMEs emerging markets reached benefitted from our financing $28.9 billion in exports facilities to targeted and investments foreign buyers $7.5B 719,200 $68B CDIA transactions Helped sustain Helped facilitate $68 billion helped Canadian companies 719,200 jobs, 3.9% of Canada’s GDP, 4% of total do $7.5 billion in business of national employment national income abroad 2 Reaching For Our Export Potential Contents Six years past the global financial crisis, by 2014 2 2014 Highlights advanced economies were gaining momentum 4 2014 Performance Measures and starting to drive global growth. While 5 EDC Around the World 6 Message from the Chair consumption in the developed world dropped 8 Message from the President 10 Message from the Chief Economist dramatically during the recession, these low 12 Helping Small Businesses Think Big activity levels created a great deal of pent-up 18 Making the Connections to Create Trade 24 Performance Against Our Objectives demand, particularly in the U.S., our largest 30 Corporate Social Responsibility 34 Investor Relations trading partner. In this environment, Canadian 36 2015 Strategic Objectives exports grew by more than 10 per cent, providing 40 Board of Directors 42 Executive Management Team a welcome offset to an increasingly soft domestic 44 Corporate Governance 48 2014 Financial Review economy. -

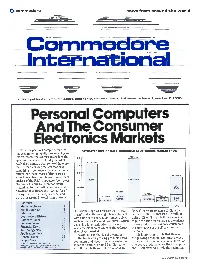

Personal Computers and the Consumer Electronics Markets

(:: c ommodore n ews from a round t h e world ! -· official publication of commodore electronics limited· nassau, bahamas ·volume 1, numbe r 2 1 983 Personal Computers And The Consumer Electronics Markets While the personal computer market ESTIMATED SIZE OF U.S.A. CONSUMER ELECTRONICS MARKETS 1982 has been growing rapidly over recent years it is an interesting exercise to see how the 30-- 29Million apparent massive size of today's market really does compare with some of the more 26.5Million 25-- mature markets for products that have something in common with personal com puters. For the purpose of this exercise 20-'- 17Million some figures have been taken from a recent analysis of the U.S.A. market for "consumer 15-- Radios Calculators electronics" done by "Merchandising" Color magazine. Another valid exercise would 10-- T.V.'s have been to compare the markets for of 6.5Million 4.5Million fice equipment such as typewriters and 5 -- 2Million Video 2Million word processors. The estimates given by B&W Games ITelephones II Video I IComputers I Recorders T.V.'s Contents Marketing News 1 Source: Merchandising Magazine Exhibition News 3 "Merchandising" are precisely that-" esti fancy if they were to gain a similar size to Editorial 5 mates" and while one might take argument either the total T.V. market of 17 million Commodore History 6 with some of the particular numbers given units or 29 million units if they were ever Company News 10 such as that for Personal Computers, which to gain the same market size as the calcula Software News 12 depends a lot on definition, this is not tor-a product that was once considered Financial News 16 really the main point which is the relative the prerogative of the office more than Technology News 17 sizes of each market. -

Advancements in Microprocessor Architecture for Ubiquitous AI—An Overview on History, Evolution, and Upcoming Challenges in AI Implementation

micromachines Review Advancements in Microprocessor Architecture for Ubiquitous AI—An Overview on History, Evolution, and Upcoming Challenges in AI Implementation Fatima Hameed Khan, Muhammad Adeel Pasha * and Shahid Masud * Department of Electrical Engineering, Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS), Lahore, Punjab 54792, Pakistan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.A.P.); [email protected] (S.M.) Abstract: Artificial intelligence (AI) has successfully made its way into contemporary industrial sectors such as automobiles, defense, industrial automation 4.0, healthcare technologies, agriculture, and many other domains because of its ability to act autonomously without continuous human interventions. However, this capability requires processing huge amounts of learning data to extract useful information in real time. The buzz around AI is not new, as this term has been widely known for the past half century. In the 1960s, scientists began to think about machines acting more like humans, which resulted in the development of the first natural language processing computers. It laid the foundation of AI, but there were only a handful of applications until the 1990s due to limitations in processing speed, memory, and computational power available. Since the 1990s, advancements in computer architecture and memory organization have enabled microprocessors to deliver much higher performance. Simultaneously, improvements in the understanding and mathematical representation of AI gave birth to its subset, referred to as machine learning (ML). ML Citation: Khan, F.H.; Pasha, M.A.; includes different algorithms for independent learning, and the most promising ones are based on Masud, S. Advancements in brain-inspired techniques classified as artificial neural networks (ANNs). -

Commodore Enters in the Play “Business Is War, I Don't Believe in Compromising, I Believe in Winning” - Jack Tramiel

Commodore enters in the play “Business is war, I don't believe in compromising, I believe in winning” - Jack_Tramiel Commodore_International Logo Commodore International was an American home computer and electronics manufacturer founded by Jack Tramiel. Commodore International (CI), along with its subsidiary Commodore Business Machines (CBM), participated in the development of the home personal computer industry in the 1970s and 1980s. CBM developed and marketed the world's best-selling desktop computer, the Commodore 64 (1982), and released its Amiga computer line in July 1985. With quarterly sales ending 1983 of $49 million (equivalent to $106 million in 2018), Commodore was one of the world's largest personal computer manufacturers. Commodore: the beginnings The company that would become Commodore Business Machines, Inc. was founded in 1954 in Toronto as the Commodore Portable Typewriter Company by Polish-Jewish immigrant and Auschwitz survivor Jack Tramiel. By the late 1950s a wave of Japanese machines forced most North American typewriter companies to cease business, but Tramiel instead turned to adding machines. In 1955, the company was formally incorporated as Commodore Business Machines, Inc. (CBM) in Canada. In 1962 Commodore went public on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), under the name of Commodore International Limited. Commodore soon had a profitable calculator line and was one of the more popular brands in the early 1970s, producing both consumer as well as scientific/programmable calculators. However, in 1975, Texas Instruments, the main supplier of calculator parts, entered the market directly and put out a line of machines priced at less than Commodore's cost for the parts. -

Sale of Amiga Trademarks and Intellectual Property Assets

SALE OF AMIGA TRADEMARKS AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY ASSETS Copyright ©2010 Pluritas, LLC. 1 “The Amiga was one of the greatest computers ever made– and for my money , it was the greatest cult computer, period” - Harry McCracken of Technologizer (July, 2010) Copyright ©2010 Pluritas, LLC. 2 KEY INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS Copyright ©2010 Pluritas, LLC. 3 Opportunity Overview Amiga IP Acquisition Opportunity Assets Available for Purchase • 702 registered and pending trademarks • Trademarks • Foreign coverage in over 100 countries including • “Powered By Amiga” Registered US Trademark Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, with “Boing Ball” Logo European Union, India, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, • Registered and Pending Trademarks for “Amiga” Mexico, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, and Logos throughout the world Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam • Amiga Stylistic Trademark Application • Seller requires a license back, and encumbrance • URLs details will be disclosed upon execution of an NDA • www.amiga.com, www.amiga.de, and other related • NDA material is available domains • Other Amiga Intellectual Property including: • Hardware Designs • Software • Operating Systems Market Application and Strategic Opportunity • Gaming: In May 2010, DFC Intelligence estimated that the total global gaming market was $60.4 billion. • PC: Gartner Research reported that global 2010 PC shipments and revenue would increase 19.7% and 12.2% respectively, year over year . This amounts to 366 .1 million units and $245 billion . • Smartphone: Gartner Research reported that Android increased its global market share by 3.5 percentage points in 2009, while Apple’s global market share grew by 6.2 percentage points in 2009. • Tablet: iSuppli reported that the Apple iPad commanded nearly 84% of the tablet market in 2010. -

A Software Perspective

Future Product Options A Software Perspective Software Engineering Department Commodore International Services Corporation Confidential Information - For Authorized Distribution Only Table of Contents ᄉ Introduction 3 Objective.........................................................................................................................................................3 Philosophy......................................................................................................................................................3 Market Segments...........................................................................................................................................3 Architectures..................................................................................................................................................4 Recommendations 5 Short-Term Recommendations....................................................................................................................5 Long-Term Recommendations.....................................................................................................................6 Other Long-Term Considerations...............................................................................................................7 System Software 8 Overview.........................................................................................................................................................8 Meme...............................................................................................................................................................9 -

From Electronic to Video Gaming (Computing in Canada: Historical

From Electronic to Video Gaming (Computing in Canada: Historical Assessment Update) Sharing the Fun: Video Games in Canada, 1950-2015 Canada Science and Technology Museum Version 2 — January 30, 2015 Jean-Louis Trudel 1 Introduction Why is the playing of games so important? Even today, the approximately two billion dollars generated in GDP for the Canadian economy by the indigenous video game industry is far outweighed by the $155 billion in annual revenues of the overall information and communications technology (ICT) field. Similarly, while the video game industry may claim about 16,000 employees, the entire ICT sector employs over 520,000 Canadians. 1 Yet, 65 video game and computer science programs have sprung up in Canadian colleges and universities to cater to this new field where 97% of new graduate hires happen within Canada. 2 Furthermore, electronic gaming has become a pervasive form of entertainment, with 61% of Canadian households reporting by 2012 that they owned at least one game console and about 30% of Canadians playing every single day. 3 With the increasing adoption of mobile platforms (smartphones, tablets) available for use throughout the day, that percentage is expected to rise. Indeed, by 2014, 54% of Canadians had played a computer or video game within the past four weeks. 4 Therefore, paying attention to an industry that is able to capture the attention of so many Canadians on a regular basis is a recognition of its catering to a very deep-seated human instinct, sometimes identified as a neotenous feature rooted in early hominid evolution. Playfulness has long been recognized as a basic wellspring of human existence. -

Commodore: Amiga, Gry Na Platformä Commodore 64, Commodore International, Amigaos, ECS, Original

3AVS2U34EE ^ Commodore: Amiga, Gry na platformÄ Commodore 64, Commodore International, AmigaOS, ECS, Original... « Kindle Commodore: Amiga, Gry na platformÄ Commodore 64, Commodore International, AmigaOS, ECS, Original Chip Set, Football Manager, Donkey Kong, Test Drive, Tetris, MOS Technology TED, Hat Trick, Commodore By Å rà dÅo: Wikipedia To download Commodore: Amiga, Gry na platformÄ Commodore 64, Commodore International, AmigaOS, ECS, Original Chip Set, Football Manager, Donkey Kong, Test Drive, Tetris, MOS Technology TED, Hat Trick, Commodore eBook, make sure you follow the web link under and download the document or get access to other information which are relevant to COMMODORE: AMIGA, GRY NA PLATFORMÄ COMMODORE 64, COMMODORE INTERNATIONAL, AMIGAOS, ECS, ORIGINAL CHIP SET, FOOTBALL MANAGER, DONKEY KONG, TEST DRIVE, TETRIS, MOS TECHNOLOGY TED, HAT TRICK, COMMODORE book. Our web service was introduced using a aspire to work as a total on-line computerized catalogue that gives usage of multitude of PDF file archive catalog. You may find many dierent types of e-publication along with other literatures from the paperwork data bank. Specific well-known issues that spread out on our catalog are trending books, answer key, test test question and solution, guide paper, skill guide, test test, user guide, owners manual, assistance instructions, maintenance handbook, and so forth. READ ONLINE [ 2.9 MB ] Reviews Complete guide! Its this sort of great read. It is probably the most awesome book i have read. I am just very easily can get a satisfaction of studying a written ebook. -- Ardith Gusikowski It is really an amazing pdf which i actually have possibly read.