Options to Expand Social Investments in 187 Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nobel Peace Speech

Nobel peace speech Associate Professor Joshua FRYE Humboldt State University USA [email protected] Macy SUCHAN Humboldt State University USA [email protected] Abstract: The Nobel Peace Prize has long been considered the premier peace prize in the world. According to Geir Lundestad, Secretary of the Nobel Committee, of the 300 some peace prizes awarded worldwide, “none is in any way as well known and as highly respected as the Nobel Peace Prize” (Lundestad, 2001). Nobel peace speech is a unique and significant international site of public discourse committed to articulating the universal grammar of peace. Spanning over 100 years of sociopoliti- cal history on the world stage, Nobel Peace Laureates richly represent an important cross-section of domestic and international issues increasingly germane to many publics. Communication scholars’ interest in this rhetorical genre has increased in the past decade. Yet, the norm has been to analyze a single speech artifact from a prestigious or controversial winner rather than examine the collection of speeches for generic commonalities of import. In this essay, we analyze the discourse of No- bel peace speech inductively and argue that the organizing principle of the Nobel peace speech genre is the repetitive form of normative liberal principles and values that function as rhetorical topoi. These topoi include freedom and justice and appeal to the inviolable, inborn right of human beings to exercise certain political and civil liberties and the expectation of equality of protection from totalitarian and tyrannical abuses. The significance of this essay to contemporary communication theory is to expand our theoretical understanding of rhetoric’s role in the maintenance and de- velopment of an international and cross-cultural vocabulary for the grammar of peace. -

Cluster Book 9 Printers Singles .Indd

PROTECTING EDUCATION IN COUNTRIES AFFECTED BY CONFLICT PHOTO:DAVID TURNLEY / CORBIS CONTENT FOR INCLUSION IN TEXTBOOKS OR READERS Curriculum resource Introducing Humanitarian Education in Primary and Junior Secondary Education Front cover A Red Cross worker helps an injured man to a makeshift hospital during the Rwandan civil war XX Foreword his booklet is one of a series of booklets prepared as part of the T Protecting Education in Conflict-Affected Countries Programme, undertaken by Save the Children on behalf of the Global Education Cluster, in partnership with Education Above All, a Qatar-based non- governmental organisation. The booklets were prepared by a consultant team from Search For Common Ground. They were written by Brendan O’Malley (editor) and Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton, Saji Prelis, and Wendy Wheaton of the Education Cluster, and technical advice from Margaret Sinclair. Accompanying training workshop materials were written by Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton and Brendan O’Malley. The curriculum resource was written by Carolyne Ashton and Margaret Sinclair. Booklet topics and themes Booklet 1 Overview Booklet 2 Legal Accountability and the Duty to Protect Booklet 3 Community-based Protection and Prevention Booklet 4 Education for Child Protection and Psychosocial Support Booklet 5 Education Policy and Planning for Protection, Recovery and Fair Access Booklet 6 Education for Building Peace Booklet 7 Monitoring and Reporting Booklet 8 Advocacy The booklets should be used alongside the with interested professionals working in Inter-Agency Network for Education in ministries of education or non- Emergencies (INEE) Minimum Standards for governmental organisations, and others Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery. -

Basics About the Red Cross

BASICS aboutBASICS the REDabout CROSS the RED CROSS I n d ian Red Cross Society Indian Red Cross Society First Edition 2008, Indian Red Cross Society Second Edition 2014, Indian Red Cross Society National Headquarters 1, Red Cross Road New Delhi 110001 India 2008, 2nd Edition © 2014, Indian Red Cross Society National Headquarters 1, Red Cross Road New Delhi 110001 India Project leader:Prof.(Dr.) S.P. Agarwal, Secretary General, IRCS Manuscript and editing: Dr. Veer Bhushan, Mr. Neel Kamal Singh, Mr. Manish Chaudhry, Ms. RinaTripathi, Mr. Bhavesh Sodagar, Dr. Rajeev Sadana, Ms. Neeti Sharma, Ms. Homai N. Modi Published by : Indian Red Cross Society, National Headquarters Supported by:International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Basics about the Red Cross Contents Idea of the Red Cross Movement .......................................................................................... 3 Foundation of the Red Cross Movement ............................................................................... 5 A Global Movement ............................................................................................................... 7 The Emblems ........................................................................................................................ 9 The Seven Fundamental Principles ...................................................................................... 13 International Humanitarian Law ........................................................................................... 21 Re-establishing Family Links -

Armed Conflict 17 Armed Conflict's Impacts on Children—A Photo Essay 37 a Basis for Action 49

CHILDREN IN WAR A Guide to the Provision of Services A Study for UNICEF Everett M. Ressler Joanne Marie Tortorici Alex Marcelino UNICEF New York, N.Y., USA Copyright © 1993 United Nations Children's Fund Programme Publications 3 UN Plaza New York, N.Y. 10017 USA ISBN: 92-806-2089-4 March 1993 Design: Phyllis Ressler Photos: Cover: Patrick Baz, AFP, 1990 Page 37: UNICEF/5549/Darko Gorenak Page 38: UNICEF/1407/Yann Gamblin Page 39: UNICEF/5526/John Isaac Page 40: David Burnett/Contact Page 41: UNICEF/2906/Carolyn Watson Page 42: UNICEF/5133/John Isaac Page 43: UNICEF/4560C/John Isaac Alon Reininger Page 44: UNICEF/833/Said Elatab UNICEF/5425/Darko Gorenak UN/141100/John Isaac Page 45: UNICEF/4761/John Chaisson Page 46: UNICEF/1397/Yann Gamblin Page 47: Leif Skoogfors Line art at beginning of chapters courtesy of International Social Service. The material in this book has been commissioned by the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF). The contents of this book are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of the United Nations Children's Fund. The designations employed in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply on the part of the United Nations Children's Fund the expression of any opinion whatsoever concerning the legal status of any country or territory or its authorities, or the delimitation of its frontiers. Oh, world be wise The future lies in children's eyes. Donna Hoffman My Children, All Children, Concordia Publishing House, St. -

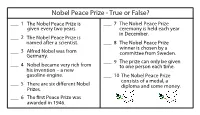

Nobel Peace Prize - True Or False?

Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___ 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___ 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. ceremony is held each year in December. ___ 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___ 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a ___ 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. ___ 9 T he prize can only be given ___ 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. his invention – a new gasoline engine. ___ 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. Prizes. ___ 6 The rst Peace Prize was awarded in 1946 . Nobel Peace Prize - True or False? ___F 1 T he Nobel Peace Prize is ___T 7 The Nobel Peace Prize given every two years. Every year ceremony is held each year in December. ___T 2 T he Nobel Peace Prize is n amed after a scientist. ___F 8 The Nobel Peace Prize winner is chosen by a Norway ___F 3 A lfred Nobel was from c ommittee from Sweden. G ermany. Sweden ___F 9 T he prize can only be given ___F 4 N obel became very rich from t o one person each time. Two or his invention – a new more gasoline engine. He got rich from ___T 10 T he Nobel Peace Prize dynamite T consists of a medal, a ___ 5 There are six dierent Nobel diploma and some money. -

Henry Dunant – Biography

Henry Dunant – Biography Jean Henri Dunantʹs life (May 8, 1828‐October 30, 1910) is a study in contrasts. He was born into a wealthy home but died in a hospice; in middle age he juxtaposed great fame with total obscurity, and success in business with bankruptcy; in old age he was virtually exiled from the Genevan society of which he had once been an ornament and died in a lonely room, leaving a bitter testament. His passionate humanitarianism was the one constant in his life, and the Red Cross his living monument. The Geneva household into which Henri Dunant was born was religious, humanitarian, and civic‐minded. In the first part of his life Dunant engaged quite seriously in religious activities and for a while in full‐time work as a representative of the Young Menʹs Christian Association, traveling in France, Belgium, and Holland. When he was twenty‐six, Dunant entered the business world as a representative of the Compagnie genevoise des Colonies de Sétif in North Africa and Sicily. In 1858 he published his first book, Notice sur la Régence de Tunis [An Account of the Regency in Tunis], made up for the most part of travel observations but containing a remarkable chapter, a long one, which he published separately in 1863, entitled LʹEsclavage chez les musulmans et aux États‐Unis dʹAmérique [Slavery among the Mohammedans and in the United States of America]. Having served his commercial apprenticeship, Dunant devised a daring financial scheme, making himself president of the Financial and Industrial Company of Mons‐Gémila Mills in Algeria (eventually capitalized at 100,000,000 francs) to exploit a large tract of land. -

List of Nobel Leaureates in Peace Year Laureates Country

List of Nobel Leaureates in Peace Year Laureates Country Rationale Henry Dunant Switzerland For his role in founding the International Committee of the Red Cross "For being one of the main founders of the Inter-Parliamentary Union and also the main organizer 1901 Frédéric Passy France of the first Universal Peace Congress" Élie Ducommun "For his role as the first honorary secretary of the International Peace Bureau" 1902 Charles Albert Gobat Switzerland "For his role as the first Secretary General of the Inter-Parliamentary Union" 1903 William Randal Cremer United Kingdom "For his role as the 'first father' of the Inter-Parliamentary Union" 1904 Institute of International Law Belgium "For its efforts as an unofficial body to formulate the general principles of the science of international law" 1905 Bertha von Suttner Austria-Hungary For writing Lay Down Your Arms and contributing to the creation of the Prize "For his successful mediation to end the Russo-Japanese war and for his interest in arbitration, 1906 Theodore Roosevelt United States having provided the Hague arbitration court with its very first case" Ernesto Teodoro Moneta Italy "For his work as a key leader of the Italian peace movement" 1907 Louis Renault France "For his work as a leading French international jurist and a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague" Klas Pontus Arnoldson Sweden "For his work as founder of the Swedish Peace and Arbitration League" "For being the foremost peace advocate in Scandinavia, combining work in the Inter-Parliamentary 1908 -

International Review of the Red Cross, July 1961, First Year

INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS Geneva LEOPOLD BOISSIER, Doctor of Laws, Honorary Professor at the University of Geneva, former Secretary-General to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, President (1946) 1 JACQUES CHENEVIERE, Hon. Doctor of Literature, Honorary Vice-President (1919) LUCIE ODIER, Former Director of the District Nursing Service, Geneva Branch of the Swiss Red Cross (1930) CARL J. BURCKHARDT, Doc~or of Philosophy, former Swiss Minister to France (1933) MARTIN BODMER, Hon. Doctor of Philosophy, Vice-President (1940) ERNEST GLOOR, Doctor of Medicine, Vice-President (1945) PAUL RUEGGER, former Swiss Minister to Italy and the United Kingdom, Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (1948), on leave RODOLFO OLGIATI, Hon. Doctor of Medicine, former Director of the Don Suisse (1949) MARGUERITE VAN BERCHEM, former Head of Section, Central Prisoners of War Agency (1951) FREDERIC SIORDET, Lawyer, Counsellor of the International Committee of the Red Cross from 1943 to 1951 (1951) GUILLAUME BORDIER, Certificated Engineer E.P.F., M.B.A. Harvard, Banker (1955) ADOLPHE FRANCESCHETTI, Doctor of Medicine, Professor of clinical ophthalmology at Geneva University (1958) HANS BACHMANN, Doctor of Laws, Assistant Secretary-General to the International Committee of the Red Cross from 1944 to 1946 (1958) JACQUES FREYMOND, Doctor of Literature, Director of the Graduate Institute of International Studies, Professor at the University of Geneva (1959) DIETRICH SCHINDLER, Doctor of Laws (1961) SAMUEL GONARD, Colonel Commandant of an Army Corps, former Professor at the Federal Polytechnical School (1961) HANS MEULI, Doctor of Medicine, Brigade Colonel, former Director of the Swiss Army Medical Service (1961) Direction: ROGER GALLOPIN, Doctor of Laws, Executive Director JEAN S. -

Peace Events of the 20Th and 21St Centuries*

Peace Events of the 20th and 21st Centuries* The 20th century witnessed the most destructive wars in human history. Perhaps as many as twenty- five million people died and countless others were wounded; millions more suffered from famine, plague, dislocation, devastation and all the other hardships war can bring. Yet the 20th century also saw the most concerted efforts ever attempted to limit and even prevent war, to constrain arms proliferation, to advance peaceful means of resolving conflicts, to protect human rights, to prosecute war crimes, to prevent genocide, and to promote peace. Listed below in chronological order are some of the more important measures undertaken during the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century in the ongoing worldwide struggle to achieve these goals. Included in the listing are such disparate events as efforts to create global and regional international bodies and other mechanisms for the peaceful resolution of disputes and conflicts; major armistices which sought not only to end wars but also promote lasting peace; treaties and other agreements meant to halt or control the spread and use of weapons, especially weapons of mass destruction; establishment of international standards to promote human rights and discourage crimes and other atrocities against nationalities, civilians, prisoners and combatants; and other significant events intended in one way or another to promote peace or oppose war. Treaties proposed more to end specific conflicts than propose a systemic and lasting peace are generally not included. Many of the treaties and other documents for which links are provided are available from more than one source. -

Peace and Conflict

Peace and Conflict Peace and Conflict Introduction Over 80 percent of all humanitarian crises are the result of conflict. Conflict is an intrinsic and inevitable aspect of social change, but how we deal with this conflict determines the impacts and outcomes of change. Understanding how conflict can be managed, utilized, and transformed can help promote more peaceful resolutions and responses. But what is peace and how is it accomplished? As peace is a hypothetical construct, it is often easiest to define what peace is not—that is, conflict. Conflict is, from the Latin, “to clash or engage in a fight,” and occurs when two or more individuals or groups pursue mutually incompatible goals. In fact, peace and conflict can take different forms, occurring on a number of levels with a wide variety of causes and outcomes. Peace and conflict occur in various contexts, from the personal, family, school, and community levels to the international level. Peace and conflict studies often involve an exploration of the interconnections among such issues as poverty, violence and non-violence, individual and overall security, hunger, discrimination, human rights, war and justice, freedom, and the human community. The interdisciplinary nature of peace and conflict studies means that teachers have lots of options in deciding what to teach and many opportunities to link their lessons with other topics or areas of inquiry. BG-9.3 Peace and Conflict Exploring the Issues 1. Understanding Concepts of Peace and Conflict Johan Galtung, one of the founders in the field of peace and conflict studies, proposed interrelated models of conflict, violence, and peace. -

Population Distribution, Urbanization, Internal Migration and Development: an International Perspective

E c o n o m i c & S o c I a l A f r s United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which Member States of the United Nations draw to review common problems and take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The designations employed in this report and the material presented in it do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The term “country” as used in the text of this publication also refers, as appropriate, to territories or areas. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries or areas and “more developed”, “less developed” and “least developed” regions are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. -

The Camera and the Red Cross: "Lamentable Pictures" and Conflict

International Review of the Red Cross (2020), 102 (913), 417–443. Digital technologies and war doi:10.1017/S1816383121000072 The camera and the Red Cross: “Lamentable pictures” and conflict photography bring into focus an international movement, 1855–1865 Sonya de Laat* Dr Sonya de Laat is a member of the Humanitarian Health Ethics research group, an Academic Adviser in the Global Health graduate programme at McMaster University, Canada, and a member of the Canadian Network on Humanitarian History. Abstract Henry Dunant’s appeal for a neutral and impartial organization to provide care to wounded combatants aligned with growing criticism of mid-nineteenth-century European and North American conflicts. This article discusses the important convergence of Dunant’s “lamentable pictures”, laid out in his Memory of * The author would like to thank her doctoral thesis committee: Sharon Sliwinski (Western University), Amanda Grzyb (Western University) and Lisa Schwartz (McMaster University). She would also like to thank Valérie Gorin (CERAH), Dominique Marshall (Carleton University) and members of the Canadian Network on Humanitarian History for comments on early drafts of this paper. Her participation in the Global Humanitarian Research Academy, along with her SSHRC and OGS doctoral awards, were invaluable in supporting research for this paper. © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the ICRC. 417 S. de Laat Solferino, with spectators’ passionate responses to them and to battlefield photographs that circulated between 1855 and 1865. Through these images and reactions, there emerged a shared, expanded vision of humanity worth caring for, which brought into focus an international humanitarian movement.