The Camera and the Red Cross: "Lamentable Pictures" and Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline / Before 1800 to 1900 / AUSTRIA / POLITICAL CONTEXT

Timeline / Before 1800 to 1900 / AUSTRIA / POLITICAL CONTEXT Date Country Theme 1797 Austria Political Context Austria and France conclude the Treaty of Campo Formio on 17 October. Austria then cedes to Belgium and Lombardy. To compensate, it gains the eastern part of the Venetian Republic up to the Adige, including Venice, Istria and Dalmatia. 1814 - 1815 Austria Political Context The Great Peace Congress is held in Vienna from 18 September 1814 to 9 June 1815. Clemens Wenzel Duke of Metternich organises the Austrian predominance in Italy. Austria exchanges the Austrian Netherlands for the territory of the Venetian Republic and creates the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. 1840 - 1841 Austria Political Context Austria cooperates in a settlement to the Turkish–Egyptian crisis of 1840, sending intervention forces to conquer the Ottoman fortresses of Saida (Sidon) and St Jean d’Acre, and concluding with the Dardanelles Treaty signed at the London Straits Convention of 1841. 1848 - 1849 Austria Political Context Revolution in Austria-Hungary and northern Italy. 1859 Austria Political Context Defeat of the Austrians by a French and Sardinian Army at the Battle of Solferino on 24 June sees terrible losses on both sides. 1859 Austria Political Context At the Peace of Zürich (10 November) Austria cedes Lombardy, but not Venetia, to Napoleon III; in turn, Napoleon hands the province over to the Kingdom of Sardinia. 1866 Austria Political Context Following defeat at the Battle of Königgrätz (3 October), at the Peace of Vienna, Austria is forced to cede the Venetian province to Italy. 1878 Austria Political Context In June the signatories at the Congress of Berlin grant Austria the right to occupy and fully administer Bosnia and Herzegovina for an undetermined period. -

Verona Family Bike + Adventure Tour Lake Garda and the Land of the Italian Fairytale

+1 888 396 5383 617 776 4441 [email protected] DUVINE.COM Europe / Italy / Veneto Verona Family Bike + Adventure Tour Lake Garda and the Land of the Italian Fairytale © 2021 DuVine Adventure + Cycling Co. Hand-craft fresh pasta during an evening of Italian hospitality with our friends Alberto and Manuela Hike a footpath up Monte Baldo, the mountain above Lake Garda that offers the Veneto’s greatest views Learn the Italian form of mild mountaineering known as via ferrata Swim or sun on the shores of Italy’s largest lake Spend the night in a cozy refuge tucked into the Lessini Mountains, the starting point for a hike to historic WWI trenches Arrival Details Departure Details Airport City: Airport City: Milan or Venice, Italy Milan or Venice, Italy Pick-Up Location: Drop-Off Location: Porta Nuova Train Station in Verona Porta Nuova Train Station in Verona Pick-Up Time: Drop-Off Time: 11:00 am 12:00 pm NOTE: DuVine provides group transfers to and from the tour, within reason and in accordance with the pick-up and drop-off recommendations. In the event your train, flight, or other travel falls outside the recommended departure or arrival time or location, you may be responsible for extra costs incurred in arranging a separate transfer. Emergency Assistance For urgent assistance on your way to tour or while on tour, please always contact your guides first. You may also contact the Boston office during business hours at +1 617 776 4441 or [email protected]. Younger Travelers This itinerary is designed with children age 9 and older in mind. -

The Other Side of the Lens-Exhibition Catalogue.Pdf

The Other Side of the Lens: Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography during the 19th Century is curated by Edward Wakeling, Allan Chapman, Janet McMullin and Cristina Neagu and will be open from 4 July ('Alice's Day') to 30 September 2015. The main purpose of this new exhibition is to show the range and variety of photographs taken by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) from topography to still-life, from portraits of famous Victorians to his own family and wide circle of friends. Carroll spent nearly twenty-five years taking photographs, all using the wet-collodion process, from 1856 to 1880. The main sources of the photographs on display are Christ Church Library, the Metropolitan Museum, New York, National Portrait Gallery, London, Princeton University and the University of Texas at Austin. Visiting hours: Monday: 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Tuesday - Thursday: 10.00 am - 1.00 pm; 2:00 pm - 4.30 pm; Friday: 10:00 am - 1.00 pm. Framed photographs on loan from Edward Wakeling Photographic equipment on loan from Allan Chapman Exhibition catalogue and poster by Cristina Neagu 2 The Other Side of the Lens Lewis Carroll and the Art of Photography ‘A Tea Merchant’, 14 July 1873. IN 2155 (Texas). Tom Quad Rooftop Studio, Christ Church. Xie Kitchin dressed in a genuine Chinese costume sitting on tea-chests portraying a Chinese ‘tea merchant’. Dodgson subtitled this as ‘on duty’. In a paired image, she sits with hat off in ‘off duty’ pose. Contents Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and His Camera 5 Exhibition Catalogue Display Cases 17 Framed Photographs 22 Photographic Equipment 26 3 4 Croft Rectory, July 1856. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

Nobel Peace Speech

Nobel peace speech Associate Professor Joshua FRYE Humboldt State University USA [email protected] Macy SUCHAN Humboldt State University USA [email protected] Abstract: The Nobel Peace Prize has long been considered the premier peace prize in the world. According to Geir Lundestad, Secretary of the Nobel Committee, of the 300 some peace prizes awarded worldwide, “none is in any way as well known and as highly respected as the Nobel Peace Prize” (Lundestad, 2001). Nobel peace speech is a unique and significant international site of public discourse committed to articulating the universal grammar of peace. Spanning over 100 years of sociopoliti- cal history on the world stage, Nobel Peace Laureates richly represent an important cross-section of domestic and international issues increasingly germane to many publics. Communication scholars’ interest in this rhetorical genre has increased in the past decade. Yet, the norm has been to analyze a single speech artifact from a prestigious or controversial winner rather than examine the collection of speeches for generic commonalities of import. In this essay, we analyze the discourse of No- bel peace speech inductively and argue that the organizing principle of the Nobel peace speech genre is the repetitive form of normative liberal principles and values that function as rhetorical topoi. These topoi include freedom and justice and appeal to the inviolable, inborn right of human beings to exercise certain political and civil liberties and the expectation of equality of protection from totalitarian and tyrannical abuses. The significance of this essay to contemporary communication theory is to expand our theoretical understanding of rhetoric’s role in the maintenance and de- velopment of an international and cross-cultural vocabulary for the grammar of peace. -

Della Fotografia “Istantanea” 1839-1865

DELLA FOTOGRAFIA “ISTANTANEA” 1839-1865 Giovanni Fanelli 2020 DELLA FOTOGRAFIA “ISTANTANEA” 1839-1865 Giovanni Fanelli 2020 L’arte ha aspirato spesso alla rappresentazione del movimento. Leonardo da Vinci fu maestro nello studio dell’ottica, della luce, del movimento e nella raffigurazione della istantaneità nei fenommeni naturali e nella vita degli esseri viventi. E anche l’arte del ritratto era per lui cogliere il movimento dell’emozione interiore. * La fotografia, per natura oggetto e bidimensionale, non può a rigor di termini riprodurre il movimento come in un certo modo può fare il cinema; può soltanto, se il fotografo ne ha l’intenzione, riprenderne un istante che nella sua fugacità riassuma la mobilità. Tuttavia fin dall’inizio della storia della fotografia i fotografi aspirarono a riprendere il movimento. Già Daguerre o Talbot aspiravano alla istantaneità. Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre, Paris, Boulevard du Temple alle 8 del mattino, fine aprile 1838, dagherrotipo, 12,9x16,3, Munich, Fotomuseum im mûnchner Stadtmuseum. Henry Fox Talbot, Eliza Freyland con in braccio Charles Henry Talbot, con Eva e Rosamond Talbot, 5 aprile 1842, stampa su carta salata da calotipo, 18,8x22,5. Bradford, The National Museum of Photography, Film & Television. Una delle prime immagini fotografiche, il dagherrotipo della veduta ripresa da Daguerre dall’alto del suo Diorama è animata : all’angolo del boulevard du Temple è presente un uomo immobile il tempo di farsi lucidare le scarpe. Le altre persone che certamente a quell’ora animavano il boulevard non appaiono perché il tempo di posa del dagherotipo era lungo (calcolabile a circa 7 minuti) (cfr. Jacques Roquencourt http://www.niepce-daguerre.com/ ). -

The Photographic Truth

The Photographic Truth! ! History of Information 103! Geoff Nunberg! ! March 18, 2014! 1! The Impact of Photography! year 2015 1980 1950 1900 1800 1700 1600 1200 600 400 0 500 3000 5000 30,000 50,000 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 10 11 12 13 14 15 week 2! Agenda, 3/17! Why photograph? The birth of the "information age"; photography and information! Photography as a technology! The photographic "truth"! Manipulating & questioning the photographic truth, then and now! Photography as documentation! Fixing identities! Documenting the deviant! Representing the other! How we read photographs! (What's left out: photography as art, popular form, etc.)! 3! The Range of "Photography"! Things we count as “photography”….! .! 4! The Range of “Photography”! Things we don’t (usually) count as photography! What defines a "technology"? Features of use, distribution, markets etc. ! 5! What makes a "technology"?! How many technologies?! telegraphy! broadcast! ?! Photography! 6! Inventions, Technologies, Applications, Media! Inventions Technology Applications Media "pre-photography" ! Official records! Newspapers, magazines! Photo- Nièpce, Dauguerre, journalism/ Talbot, Archer, etc.! documentary! ! PHOTOGRAPHY "Art" Cartes de visite, photography! snapshots, Collodion, dry commemorative, plate...! advertiising, Consumer porn, fashion photography! etc,! ! Photolithography, Micro- color, Scientific photography etc.! phototelegraphy, uses! digital, etc. ! Surveillance, military, 7! forensic, etc.! Multiple Influences! Market forces! Mass press Photographic & printing ! technology! Magazines Documentary Ideological photography background! Books & expositions Public attitudes! Cultural Setting! 8! Modern Marvels! "Only on looking back, fifty years later, at his own figure in 1854, and pondering on the needs of the twentieth century, he wondered whether, on the whole, the boy of 1854 stood nearer to the thought of 1904, or to that of the year 1 .. -

O Du Mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in The

O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 ABSTRACT O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the Austro-Hungarian Empire by Jason Stephen Heilman Department of Music Duke University Date: _______________________ Approved: ______________________________ Bryan R. Gilliam, Supervisor ______________________________ Scott Lindroth ______________________________ James Rolleston ______________________________ Malachi Hacohen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2009 Copyright by Jason Stephen Heilman 2009 Abstract As a multinational state with a population that spoke eleven different languages, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was considered an anachronism during the age of heightened nationalism leading up to the First World War. This situation has made the search for a single Austro-Hungarian identity so difficult that many historians have declared it impossible. Yet the Dual Monarchy possessed one potentially unifying cultural aspect that has long been critically neglected: the extensive repertoire of marches and patriotic music performed by the military bands of the Imperial and Royal Austro- Hungarian Army. This Militärmusik actively blended idioms representing the various nationalist musics from around the empire in an attempt to reflect and even celebrate its multinational makeup. -

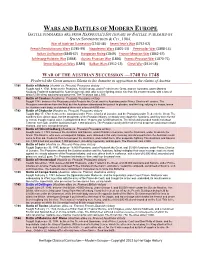

Wars and Battles of Modern Europe Battle Summaries Are from Harbottle's Dictionary of Battles, Published by Swan Sonnenschein & Co., 1904

WARS AND BATTLES OF MODERN EUROPE BATTLE SUMMARIES ARE FROM HARBOTTLE'S DICTIONARY OF BATTLES, PUBLISHED BY SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., 1904. War of Austrian Succession (1740-48) Seven Year's War (1752-62) French Revolutionary Wars (1785-99) Napoleonic Wars (1801-15) Peninsular War (1808-14) Italian Unification (1848-67) Hungarian Rising (1849) Franco-Mexican War (1862-67) Schleswig-Holstein War (1864) Austro Prussian War (1866) Franco Prussian War (1870-71) Servo-Bulgarian Wars (1885) Balkan Wars (1912-13) Great War (1914-18) WAR OF THE AUSTRIAN SUCCESSION —1740 TO 1748 Frederick the Great annexes Silesia to his domains in opposition to the claims of Austria 1741 Battle of Molwitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought April 8, 1741, between the Prussians, 30,000 strong, under Frederick the Great, and the Austrians, under Marshal Neuperg. Frederick surprised the Austrian general, and, after severe fighting, drove him from his entrenchments, with a loss of about 5,000 killed, wounded and prisoners. The Prussians lost 2,500. 1742 Battle of Czaslau (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought 1742, between the Prussians under Frederic the Great, and the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine. The Prussians were driven from the field, but the Austrians abandoned the pursuit to plunder, and the king, rallying his troops, broke the Austrian main body, and defeated them with a loss of 4,000 men. 1742 Battle of Chotusitz (Austria vs. Prussia) Prussians victory Fought May 17, 1742, between the Austrians under Prince Charles of Lorraine, and the Prussians under Frederick the Great. The numbers were about equal, but the steadiness of the Prussian infantry eventually wore down the Austrians, and they were forced to retreat, though in good order, leaving behind them 18 guns and 12,000 prisoners. -

Cluster Book 9 Printers Singles .Indd

PROTECTING EDUCATION IN COUNTRIES AFFECTED BY CONFLICT PHOTO:DAVID TURNLEY / CORBIS CONTENT FOR INCLUSION IN TEXTBOOKS OR READERS Curriculum resource Introducing Humanitarian Education in Primary and Junior Secondary Education Front cover A Red Cross worker helps an injured man to a makeshift hospital during the Rwandan civil war XX Foreword his booklet is one of a series of booklets prepared as part of the T Protecting Education in Conflict-Affected Countries Programme, undertaken by Save the Children on behalf of the Global Education Cluster, in partnership with Education Above All, a Qatar-based non- governmental organisation. The booklets were prepared by a consultant team from Search For Common Ground. They were written by Brendan O’Malley (editor) and Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton, Saji Prelis, and Wendy Wheaton of the Education Cluster, and technical advice from Margaret Sinclair. Accompanying training workshop materials were written by Melinda Smith, with contributions from Carolyne Ashton and Brendan O’Malley. The curriculum resource was written by Carolyne Ashton and Margaret Sinclair. Booklet topics and themes Booklet 1 Overview Booklet 2 Legal Accountability and the Duty to Protect Booklet 3 Community-based Protection and Prevention Booklet 4 Education for Child Protection and Psychosocial Support Booklet 5 Education Policy and Planning for Protection, Recovery and Fair Access Booklet 6 Education for Building Peace Booklet 7 Monitoring and Reporting Booklet 8 Advocacy The booklets should be used alongside the with interested professionals working in Inter-Agency Network for Education in ministries of education or non- Emergencies (INEE) Minimum Standards for governmental organisations, and others Education: Preparedness, Response, Recovery. -

Champions for Humanity

BELIZE RED CROSS Champions for Humanity VOLUME 1, ISSUE 02 MAY/JUNE 2 0 1 9 A Nobel Prize, A Noble Man In this issue: The Red Cross is an international humanitarian Movement founded in 1863 in Switzer- land, with National Societies worldwide that provide assistance to persons affected by A history of Red disasters and crises, armed conflict and health crises. Roots of the Red Cross date back Cross to 1859, when Swiss businessman, Henry Dunant, witnessed the bloody aftermath of the Battle of Solferino in Italy, where there was little medical support for injured soldiers. Du- Project Updates nant went on to advocate for the establishment of national relief organizations made up of trained volunteers who could offer assistance to war-wounded soldiers, regardless of Opportunity which side of the battle they were on. In 1859, The bloody battle was between Franco Spotlight -Sardinian and Austrian forces near the small village of Solferino, Italy. The fighting had left some 40,000 troops dead, wounded or missing, and both the armies, as well as the residents of the region, were ill-equipped to deal with the situation. By 1862, Dunant published a book, Memories of Solferino, in which he advocated for the establishment of national relief organizations . The following year, Dunant was part of a Swiss-based committee that put together a plan for national relief associa- tions. The group, which eventually became known as the International Committee of the Red Cross, adopted the symbol of a red cross on a white background, an inversion of the Swiss flag, as a way to identify medical workers on the battlefield. -

Basics About the Red Cross

BASICS aboutBASICS the REDabout CROSS the RED CROSS I n d ian Red Cross Society Indian Red Cross Society First Edition 2008, Indian Red Cross Society Second Edition 2014, Indian Red Cross Society National Headquarters 1, Red Cross Road New Delhi 110001 India 2008, 2nd Edition © 2014, Indian Red Cross Society National Headquarters 1, Red Cross Road New Delhi 110001 India Project leader:Prof.(Dr.) S.P. Agarwal, Secretary General, IRCS Manuscript and editing: Dr. Veer Bhushan, Mr. Neel Kamal Singh, Mr. Manish Chaudhry, Ms. RinaTripathi, Mr. Bhavesh Sodagar, Dr. Rajeev Sadana, Ms. Neeti Sharma, Ms. Homai N. Modi Published by : Indian Red Cross Society, National Headquarters Supported by:International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Basics about the Red Cross Contents Idea of the Red Cross Movement .......................................................................................... 3 Foundation of the Red Cross Movement ............................................................................... 5 A Global Movement ............................................................................................................... 7 The Emblems ........................................................................................................................ 9 The Seven Fundamental Principles ...................................................................................... 13 International Humanitarian Law ........................................................................................... 21 Re-establishing Family Links