Kyiv-Mohyla Humanities Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toronto Pays Tribute to Former Soviet Political Prisoner However, Mr

INSIDE:• Leadership Conference focuses on Ukrainian American community — page 3. • New York pastor celebrates 50th jubilee — page 5. • The UNA’s former headquarters in Jersey City: an appreciation — centerfold. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXV HE No.KRAINIAN 42 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, OCTOBER 19, 1997 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine ForeignT InvestmentU Council strives Verkhovna RadaW acts quickly on changes to make Ukraine business-friendly to election law suggested by president by Roman Woronowycz which is more sympathetic to the needs of by Roman Woronowycz ing with Article 94 of the Constitution of Kyiv Press Bureau businesses, and the predominantly leftist Kyiv Press Bureau Ukraine.” legislature has also led to constantly But the Verkhovna Rada speedily KYIV — The President’s Foreign changing statutes that affect the business KYIV — Ukraine’s Parliament moved made room on its agenda of October 14 Investment Advisory Council met for the community. One of Motorola’s reasons quickly to smooth any further roadblocks and in one session passed 13 of the pro- first time on October 3 to begin the work for abandoning its deal with Ukraine were to a new law on elections on October 14 posals and rejected two, most notably a of making Ukraine more amicable to for- the “ever-changing rules of the game,” when it acted in one day to incorporate recommendation that a 50 percent eign businesses. Although Ukraine’s said its Ukraine director at the time it can- most changes requested by the president. turnout in electoral districts remain a president and government officials tried celed its contract with the government. -

Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics: Implications For

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTIO N AUTHORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky Tönu Parming CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATORS : Yaroslav Bilinsky, Project Director an d Co-Principal Investigato r Tönu Parming, Co-Principal Investigato r COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research . NOTICE OF INTENTION TO APPLY FOR COPYRIGH T This work has been requested for manuscrip t review for publication . It is not to be quote d without express written permission by the authors , who hereby reserve all the rights herein . Th e contractual exception to this is as follows : The [US] Government will have th e right to publish or release Fina l Reports, but only in same forma t in which such Final Reports ar e delivered to it by the Council . Th e Government will not have the righ t to authorize others to publish suc h Final Reports without the consent o f the authors, and the individua l researchers will have the right t o apply for and obtain copyright o n any work products which may b e derived from work funded by th e Council under this Contract . ii EXEC 1 Overall Executive Summary HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR THE SOVIET NATIONALITY QUESTION by Yaroslav Bilinsky, University of Delawar e d Tönu Parming, University of Marylan August 1, 1975, after more than two years of intensive negotiations, 35 Head s of Governments--President Ford of the United States, Prime Minister Trudeau of Canada , Secretary-General Brezhnev of the USSR, and the Chief Executives of 32 othe r European States--signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperatio n in Europe (CSCE) . -

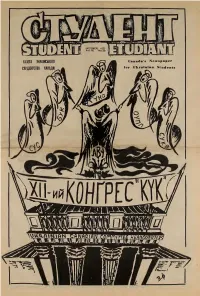

STUDENT 1977 October

2 «««««••••••«•»» : THE PRESIDENT : ON SUSK Andriy Makuch : change in attitude is necessary. • • The book of Samuel relates how This idea was reiterated uyzbyf the young David stood before • Marijka Hurko in opening the I8th S • Goliath and proclaimed his In- Congress this year, and for- tention slay him. The giant was 2 3 to malized by Andrij Semotiuk's.© • amazed and took tight the threat; presentation of "The Ukrainian • subsequently, he was struck down • Students' Movement In Context" J • by a well-thrown rock. Since then, (to be printed in the next issue of • giants have taken greater heed of 2 STUDENT). It was a most listless such warnings. 2 STUDENT • Congress - the • seek and disturbing " I am not advocating we 11246-91 St. ritual burying of an albatross wish to J Edmonton. Alberta 2 Goliaths to slay, but rather mythology. There were no great • underline that a well-directed for- Canada TSB 4A2 funeral orations, no tears cried. ce can be very effective • par- • No one cared. Not that they were f ticularly if it is judiciously applied. the - incapable of it, but because , SUSK must keep this in mind over , £ entire issue was so far removed 5 9• the coming yeayear. The problems ' trom their own reality (especially ft . t we, as part off thett Ukrainian corn- - those attending their first " £ . community, no face are for- - Congress), that they had no idea • midable, andi theretht is neither time of why they should. Such a sad and bi-monthly news- nor manpower to waste. "STUDENT" is a national tri- ft spectacle must never be repeated by • The immediate necessity is to students and is published - entrenched Ideas can be very • paper for Ukrainian Canadian realistically assess our priorities 2 limiting. -

Reconceptualizing the Alien: Jews in Modern Ukrainian Thought*

Ab Imperio, 4/2003 Yohanan PETROVSKY-SHTERN RECONCEPTUALIZING THE ALIEN: JEWS IN MODERN UKRAINIAN THOUGHT* To love ones motherland is no crime. From Zalyvakhas letter to Svitlychnyi, Chornovil, and Lukho. Whoever in hunger eats the grass of the motherland is no criminal. Andrei Platonov, The Sand Teacher Perhaps one of the most astounding phenomena in modern Ukrainian thought is the radical reassessment of the Jew. Though the revision of Jew- ish issues began earlier in the 20th century, if not in the late 19th, it became particularly salient as part of the new political narrative after the “velvet revolution” of 1991 that led to the demise of the USSR and the establish- * I gratefully acknowledge the help of two anonymous reviewers of Ab Imperio whose insightful comments helped me considerably to improve this paper. Ukrainian names in the body text are rendered in their Library of Congress Ukrainian transliteration. In cases where there is an established English (or Russian) form for a name, it is bracketed following the Ukrainian version. The spelling in the footnotes does not follow LC Ukrainian transliteration except in cases where the publishers provide their own spelling. 519 Y. Petrovsky-Shtern, Reconceptualizing the Alien... ment of an independent Ukraine. The new Ukrainian perception of the Jew boldly challenged the received bias and created a new social and political environment fostering the renaissance of Jewish culture in Ukraine, let alone Ukrainian-Jewish dialogue. There were a number of ways to explain what had happened. For some, the sudden Ukrainian-Jewish rapprochement was a by-product of the new western-oriented post-1991 Ukrainian foreign pol- icy. -

Abn Correspondence Bulletin of the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations

FREEDOM FOR NATIONS ! CORRESPONDENCE FREEDOM FOR INDIVIDUALS! JANUARY-FEBRUARY 1989 CONTENTS: Carolling Ukrainian-Style ....................... 2 The Autobiography of Levko Lukyanenko ..................... 3 European Freedom Council Meeting ..............................16 Statement of the European Freedom Council .............. 16 Hon. John Wilkinson, M.P. Eastern European Policy for Western Europe .............. 19 Genevieve Aubry, M.P. Is Switzerland Ready for a New Challenge with the European Nations .......................... 26 Sir Frederic Bennett Can the Soviet Russian Empire Survive? ....................... 31 Bertil Haggman Aiding the Forces of Freedom in the Soviet Empire ................................... 34 Ukrainian Christian Democratic Front Holds Inaugural Meeting ........... 40 David Remnick Ukraine Could be Soviets’ Next Trouble Spot ..............41 Bohdan Nahaylo Specter of the Empire Haunts the Soviet Union ..........45 Appeal to the Russian Intelligentsia ......... ......................47 Freedom for Nations! Freedom for Individuals! ABN CORRESPONDENCE BULLETIN OF THE ANTI-BOLSHEVIK BLOC OF NATIONS Publisher and Owner (Verleger und Inha It is not our practice to pay for contribut ber): American Friends of the Anti-Bolshevik ed materials. Reproduction permitted only Bloc of Nations (AF ABN), 136 Second Avenue, with indication of source (ABN Corr.). New York, N.Y. 10003, USA. Annual subscription: 27 Dollars in the Zweigstelle Deutschland: A. Dankiw, USA, and the equivalent of 27 US Dollars in Zeppelinstr. 67, 8000 München 80. all other countries. Remittances to Deutsche Editorial Staff: Board of Editors Bank, Munich, Neuhauser Str. 6, Account Editor-in-Chief: Mrs. Slava Stetsko, M.A. No. 3021003, Anna Dankiw. Zeppelinstr. 67 Schriftleitung: Redaktionskollegium. 8000 München 80 Verantw. Redakteur Frau Slava Stetzko. West Germany Zeppelinstraße 67 Articles signed with name or pseudonym 8000 München 80 do not necessarily reflect the Editor’s opinion, Telefon: 48 25 32 but that of the author. -

![5 March 1972 [Moscow]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6227/5-march-1972-moscow-1446227.webp)

5 March 1972 [Moscow]

á }<. [This is a rather literal translation of copies of the type- written Russian original, which was edited anonymously in Moscow and began to circulate there in sulnizdat in the first week of April 1972, Only the words in square brackets have been added by the translators.] howt 24 The Movement in Defence of Human Rights in the USSR Continues A Chronic e of Current Events "Everyow has the right to free- Chnn of opinion and evpression; this right includes freedom to hold ophdons without interference and to seek, receive and hnpart infor- mathm and ideas Ihnntgh any media and regardless of frontiers." Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 19 Issue No. 24 5 March 1972 [Moscow] CONTENTS The case of Vladimir Bukovsky [p. 115]. Searches and arrests in january [p. 119]. The hunger strike of Fainberg and Borisov [p. 126]. Bonfield prisoners in the Mordovian camps [p. 127]. Religious persecution in Lithuania [p. 129]. Document of the World Federation for Mental Health [p. 131]. The Jewish Movement to leave for Israel [p. 132]. Material from newspaper articles [p. 135]. Extra judicial persecution [p. 137]. News in brief [p. 140]. Swnizdat news [p. 148]. FIFTH YEAR OF PUBLICATION 113 The Case of Vladimir linkovsky On 5 January the Moscow City Court passed sentence on Vladimir Bukovsky (see ('hnnilde NO, 23'). For Soviet readers the only Official source of informa- tion on the trial of Vladimir Bukovsky was an arbele by Yurov and I.. Kolesov, "Biograph\ of villainy-, pull- led in the newspaper /trening Mitscuir on 6 limuary. lescrihe the article it is enom.fh to say: Mai it does not even give the sentence in kw— the points specifying con- linemont in prison and the imposition or co, m; -tre k quitted. -

Memorialization of the Jewish Tragedy at Babi Yar Aleksandr Burakovskiy∗

Nationalities Papers Vol. 39, No. 3, May 2011, 371–389 Holocaust remembrance in Ukraine: memorialization of the Jewish tragedy at Babi Yar Aleksandr Burakovskiy∗ Independent Scholar, United States (Received 24 November 2009; final version received 26 January 2011) At the core of the debate in Ukraine about Babi Yar lies the Holocaust. Between 1941 and 1943 1.5 million Jews perished in Ukraine, yet a full understanding of that tragedy has been suppressed consistently by ideologies and interpretations of history that minimize or ignore this tragedy. For Soviet ideologues, admitting to the existence of the Holocaust would have been against the tenet of a “Soviet people” and the aggressive strategy of eliminating national and religious identities. A similar logic of oneness is being applied now in the ideological formation of an independent Ukraine. However, rather than one Soviet people, now there is one Ukrainian people under which numerous historical tragedies are being subsumed, and the unique national tragedies of other peoples on the territory of Ukraine, such as the massive destruction of Jews, is again being suppressed. According to this political idea assiduously advocated most recently during the Yushchenko presidency, the twentieth century in Ukraine was a battle for liberation. Within this new, exclusive history, the Holocaust, again, has found no real place. The author reviews the complicated history regarding the memorialization of the Jewish tragedy in Babi Yar through three broad chronological periods: 1943–1960, 1961–1991, and 1992–2009. Keywords: Babi Yar; Jews in Ukraine; anti-Semitism; Holocaust At the core of the decades-long debate in Ukraine about the memorialization of the Jewish tragedy at Babi Yar lies a lack of acknowledgement of the Holocaust. -

The Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics

FINAL REPORT T O NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE : The Helsinki Watch Committees i n the Soviet Republics : Implica - tions for Soviet Nationalit y Policy AUTHOR : Yaroslav Bilinsky T8nu Parmin g CONTRACTOR : University of Delawar e PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Yaroslav Bilinsk y COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 621- 9 The work leading to this report was supported in whole or in part from funds provided by the National Council for Sovie t and East European Research . Yaroslav Bilinsky (University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19711, USA ) Tönu Parmin g (University of Maryland, College Park, ND 20742, USA ) HELSINKI WATCH COMMITTEES IN THE SOVIET REPUBLICS : IMPLICATIONS FOR SOVIETY NATIONALITY POLICY * Paper presented at Second World Congres s on Soviet and East European Studies , Garmisch-Partenkirchen, German Federal Republic , September 30 - October 4, 198 0 *This paper is based on the authors' longer study, The Helsinki Watch Committees in the Soviet Republics : Implications for the Sovie t Nationality Question, which was supported in whole or in part fro m funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East Europea n Research, under Council Contract Number 621-9 . Travel to Garmisch- Partenkirchen has been--in Bilinsky's case—made possible by grant s from the American Council of Learned Societies and the University o f Delaware . The authors would like to thank their benefactors an d explicitly stress that the authors alone are responsible for th e contents of this paper . 2 Unexpectedly, within two years of the signing by the Sovie t Union, the United States, Canada, and thirty-two European states , of the long and solemn Final Act of the Conference on Security an d Cooperation in Europe in Helsinki, August l, 1975, there sprang u p as many as five groups of Soviet dissenters claiming that th e Helsinki Final Act justified their existence and activity . -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1978, No.13

www.ukrweekly.com I CBObOAAXSVOBODA І І Ж Щ УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОАСННИК ЧЩд^Р UKRAINIAN DAILV Щ Щ Ukrainian Weekly ENGLISH" LANGUAGE WEEKLY EDITION Ш VOL. LXXXV No. 73 25 CENTS No. 73 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 2,1978 Goldberg: CSCE Was Success Matusevych, Marynovych Sentenced by Boris Potapenko '' Visti'' International News Service WASHINGTON, D.C.—The Uni spoke of human rights at the beginning ted States performance at the recently of the conference, the ambassador felt concluded Conference on Security and that it was a great achievement that 24 Cooperation in Europe was examined countries made human rights a signifi Tuesday, March 21, by Ambassador cant point of their concluding state Arthur Goldberg, who testified before ments. the U.S. Commission and Security and Ambassador Goldberg disagreed Cooperation in Europe. with the portrayal of the Belgrade The former Supreme Court Justice meeting as an event high in rhetoric but who headed the U.S. delegation, de low in substance, and also the view that fended U.S. strategy in Belgrade, and the inability to get human rights men was overwhelmingly positive and opti tioned in the final document and the mistic in both his oral and written failure to reach consensus on over 100 statements to the commission concern new proposals was proof that the confer ing the review conference and the fu ence was unsuccessful. ture of the Helsinki process. The ambassador maintained that Mykola Matusevych Myroslav Marynovych Ambassador Goldberg told the com the process begun with the signing of NEW YORK, N.Y.—Mykola Matb- the trial in Vasylkiv, a town south of mission that "the Belgrade conference the Final Act in 1975 is a gradual one, sevych and Myroslav Marynovych, Kiev. -

Contributions by Canadian Social Scientists to the Study of Soviet Ukraine During the Cold War

Contributions by Canadian Social Scientists to the Study of Soviet Ukraine During the Cold War Bohdan Harasymiw University of Calgary Abstract: This article surveys major publications concerning Ukraine by Canadian social scientists of the Cold War era. While the USSR existed, characterized by the uniformity of its political, economic, social, and cultural order, there was little incentive, apart from personal interest, for social scientists to specialize in their research on any of its component republics, including the Ukrainian SSR, and there was also no incentive to teach about them at universities. Hence there was a dearth of scholarly work on Soviet Ukraine from a social-scientific perspective. The exceptions, all but one of them émigrés—Jurij Borys, Bohdan Krawchenko, Bohdan R. Bociurkiw, Peter J. Potichnyj, Wsevolod Isajiw, and David Marples—were all the more notable. These authors, few as they were, laid the foundation for the study of post-1991 Ukraine, with major credit for disseminating their work going to the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) Press. Keywords: Canadian, social sciences, Soviet Ukraine, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. hen Omeljan Pritsak, in a paper he delivered at Carleton University in W January 1971, presented his tour d’horizon on the state of Ukrainian studies in the world, he barely mentioned Canada (139-52). Emphasizing the dearth of Ukrainian studies in Ukraine itself, his purpose was to draw attention to the inauguration of North America’s first Chair of Ukrainian Studies, at Harvard University. Two years later, of course, the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute was formed, with Pritsak as inaugural director. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1977, No.31

www.ukrweekly.com СВОБОДАІЦSVOBODA П П УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ щоденник чШвКУ UKBAINIANOAIIV rainiaENGLISH LANGUAGnE WEEKL YWeelc EDITION f Ї VOL. LXXXIVШ No. 181 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 21,1977 25CEKS^ ^n American Lawyer Wishes to Defend Terelya Arrested After Marynovych, Matusevych Denouncing Soviet Asylums SoWef Dissidents Appeal to West for Assistance NEW YORK, N.Y.—Yosyp Terelya, nek as being a member of the Moscow a 34-year-old Ukrainian poet and one- Group to Promote the implementation time political prisoner, was re-arrested of the Helsinki Accords, and Kaplun as by the KGB last April after making a being a Soviet dissident. The other two strong indictment of Soviet psychiatric persons are unknown in the West. abuses, reported the press service of the Terelya'e case also attracted the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council attention of western journalists, in his (abroad). Wednesday, August 17th column, no- Terelya, who already spent 14 years ted American investigative columnist, in prison, was "driven to despair" by the Jack Anderson, described the tortures repressions he faced during his brief experienced by Terelya during his period of freedom late last year, said prison and psychiatric asylum confine– members of the Soviet affiliate of the ments. Committee Against Psychiatric Abuse Terelya was born in 1943 in the Myroslav Marynovych Mykola Matusevych for Political Purposes, and he wrote in a Transcarpathian region of Ukraine. .letter to Y. Andropov, the KGB chief, The four Soviet dissidents noted in their NEW YORK, N.Y.—An American jobs for supporting the plight of politi– that Soviet mental asylums "would have appeal that Terelya quickly began to bW;bjfca^ lojewe asadefense cal prisoners. -

Final-Signatory List-Democracy Letter-23-06-2020.Xlsx

Signatories by Surname Name Affiliation Country Davood Moradian General Director, Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies Afghanistan Rexhep Meidani Former President of Albania Albania Juela Hamati President, European Democracy Youth Network Albania Nassera Dutour President, Federation Against Enforced Disappearances (FEMED) Algeria Fatiha Serour United Nations Deputy Special Representative for Somalia; Co-founder, Justice Impact Algeria Rafael Marques de MoraisFounder, Maka Angola Angola Laura Alonso Former Member of Chamber of Deputies; Former Executive Director, Poder Argentina Susana Malcorra Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina; Former Chef de Cabinet to the Argentina Patricia Bullrich Former Minister of Security of Argentina Argentina Mauricio Macri Former President of Argentina Argentina Beatriz Sarlo Journalist Argentina Gerardo Bongiovanni President, Fundacion Libertad Argentina Liliana De Riz Professor, Centro para la Apertura y el Desarrollo Argentina Flavia Freidenberg Professor, the Institute of Legal Research of the National Autonomous University of Argentina Santiago Cantón Secretary of Human Rights for the Province of Buenos Aires Argentina Haykuhi Harutyunyan Chairperson, Corruption Prevention Commission Armenia Gulnara Shahinian Founder and Chair, Democracy Today Armenia Tom Gerald Daly Director, Democratic Decay & Renewal (DEM-DEC) Australia Michael Danby Former Member of Parliament; Chair, the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee Australia Gareth Evans Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Australia and